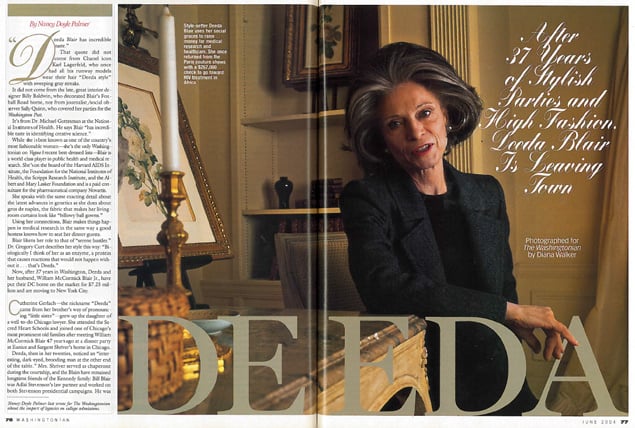

“Deeda Blair has incredible taste.”

That quote did not come from Chanel icon Karl Lagerfeld, who once had all his runway models wear their hair “Deeda style” with sweeping gray streaks.

It did not come from the late, great interior designer Billy Baldwin, who decorated Blair’s Foxhall Road home, nor from journalist/social observer Sally Quinn, who covered her parties for the Washington Post.

It’s from Dr. Michael Gottesman at the National Institutes of Health. He says Blair “has incredible taste in identifying creative science.”

While she is best known as one of the country’s most fashionable women—she’s the only Washingtonian on Vogue’s recent best-dressed lists—Blair is a world-class player in public health and medical research. She’s on the board of the Harvard AIDS Institute, the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health, the Scripps Research Institute, and the Albert and Mary Lasker Foundation and is a paid consultant for the pharmaceutical company Novartis.

She speaks with the same exacting detail about the latest advances in genetics as she does about gros de naples, the fabric that makes her living-room curtains look like “billowy ball gowns.”

Using her connections, Blair makes things happen in medical research in the same way a good hostess knows how to seat her dinner guests.

Blair likens her role to that of “serene hustler.” Dr. Gregory Curt describes her style this way: “Biologically I think of her as an enzyme, a protein that causes reactions that would not happen without it . . . that’s Deeda.”

Now, after 37 years in Washington, Deeda and her husband, William McCormick Blair Jr., have put their DC home on the market for $7.25 million and are moving to New York City.

Catherine Gerlach—the nickname “Deeda” came from her brother’s way of pronouncing “little sister”—grew up the daughter of a well-to-do Chicago lawyer. She attended the Sacred Heart Schools and joined one of Chicago’s most prominent old families after meeting William McCormick Blair 47 years ago at a dinner party at Eunice and Sargent Shriver’s home in Chicago.

Deeda, then in her twenties, noticed an “interesting, dark-eyed, brooding man at the other end of the table.” Mrs. Shriver served as chaperone during the courtship, and the Blairs have remained longtime friends of the Kennedy family. Bill Blair was Adlai Stevenson’s law partner and worked on both Stevenson presidential campaigns. He was named ambassador to Denmark by President Kennedy and served as ambassador to the Philippines under President Johnson. He went on to become the first general director of the Kennedy Center at the request of Robert F. Kennedy. Later he practiced law at the Washington firm Surrey & Morse until retirement.

An influential friend of the young couple’s was New York philanthropist Mary Lasker, who tutored Deeda in the art of raising money for medical research. The Lasker Foundation, started in 1942, annually honors discoveries in medical science. Mary Lasker was seminal to the growth of NIH and of cancer research.

Lasker knew how to bring the right people together at the right places, an art that Deeda Blair has come to perfect. Lasker would spend summers in a villa called La Fiorentina in Cap Ferrat on the French Riviera, recalls Blair, where she would mix glamorous houseguests among doctors and businesspeople.

“It was a landscape that looked social, but people were being put together,” she says with her hushed diction that sounds almost secretive.

“Wh en I was a very little girl, maybe three or four, my godmother gave me a pink crepe dress from Paris,” says Blair, drawing deeply on a cigarette. “It maybe had a thousand pleats in it, and I thought it was heaven. . . . The Paris pleated dress began it all.”

A devotee of Chanel, Givenchy, and St. Laurent as well as American designer Ralph Rucci, Blair is a fixture at the Paris shows as well as a close friend of many of the designers’. She is known for having signature details added to pieces she buys. “It may be egoism,” she says, “but it becomes something just made for me.

“Something was inculcated into me that I’d rather have very few clothes and have them be as wonderful as possible,” she says. But she adds, “I don’t dress to astonish.”

Her clothes reflect a style that is understated, detailed, and slightly mysterious. And perfect? “I don’t want to think I’m a perfectionist,” she says, “but I do prefer it to something casual.”

She doesn’t always leave the Paris shows with just a new gown—recently she returned with checks totaling $267,000 to buy an automatic sequencer to analyze different strains of HIV in Africa.

“She has a certain code,” says Vanity Fair writer Marie Brenner. “She loves serenity. Her home has stone-colored walls, white flowers. It’s an aesthetic that is both rarefied and unusual.”

The Blairs’ home has been the site of glittery evenings that may never be duplicated in Washington. The house, a 1930s Georgian mansion, has garden-level family rooms that have hosted up to 200 guests to help Democrats run for office, toast Nobel laureates, and help the ladies who lunch honor the likes of Hubert de Givenchy.

Despite the parties, Blair has maintained a low social profile here. Good friend Jane Stanton Hitchcock, author of the novel Social Crimes, says that the Blairs’ set falls into the category of “people you really want to know are the ones you’ve never really heard of.”

Cathy and Stephen Graham, daughter-in-law and son of the late Katharine Graham, are New York friends who look forward to seeing more of her in the city. “She knows herself, knows her taste, knows what she loves, and is so much fun,” says Cathy. “She is more curious and open than anyone I know and gets on with the most unlikely people . . . and what I like best about her is that she has no edge and nothing to prove.”

But what about the smoking? “It’s her little devil,” says Hitchcock. “It keeps her from being a complete saint.” And although she is a voluminous letter writer, she can’t type or e-mail. She dictates into a tape recorder, employs two secretaries—and often works from her bed, which is stacked with papers, files, and books. “The bad habit of a lifetime,” she says.

She swims daily to stay in shape—”with my head above water the whole time so my hair won’t get wet”—and embraced the benefits of a low-carb diet long before it became the latest fad. She’s an excellent cook and, again, changes each recipe to make it her own. “She serves these soufflés at lunch that are the size of the Empire State Building,” says Brenner, “and there are always the most exquisite roses.” Among Blair’s passions are arranging flowers and gardening, and she and her husband will miss their Foxhall Road aerie when they move to Manhattan.

“People used to invite us to their weekend houses in Virginia or the Eastern Shore and I’d say, ‘No, thank you,’ ” says Bill Blair, “we have a country house right here.” He also swims daily and is an avid movie fan, often attending weekday matinees.

As ambassador to Denmark, he began a tradition of getting first-run movies and, with Deeda, inviting guests to the film and dinner afterward.

The Blairs’ son, William, attended St. Albans and St. James schools as well as American University. He is also leaving Washington, to pursue a “stress-free” life in California. William, who embodies both parents’ good looks, runs a professional dog-walker/house-sitter business and plans to continue on the West Coast.

Bill Blair is modest, particularly for a career Washingtonian. “I find you accomplish more by not making a big fuss about it,” he says. He is wistful about leaving their life in Washington.

“I remember the first time I ever covered a party at her house,” recalls Sally Quinn, “and I was so struck by how beautiful everything was and sort of pale. . . . Vogue would call it ‘inside of the spring leaf green and white,’ all so beautiful and pristine. The hors d’oeuvres matched the room, and Deeda had on a pale green dress that matched everything, and I thought it was the most spectacular thing . . . and that she was unlike anyone else in Washington.”

This article appears in the June 2004 issue of The Washingtonian.