Back in the mid-1990s, a college student at a large public university in the Pacific Northwest tacked up a poster of John F. Kennedy in his dorm room, an ever-present reminder of the challenge JFK laid down in his inaugural address: “Ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country.”

The student, the son of a university professor, took those electrifying words to heart. After majoring in political science, he landed an internship with his state senator. A stint at the Office of the United States Trade Representative was followed by public-policy school, which paved the way to the prestigious Presidential Management Fellowship, a government-leadership program for those with advanced degrees.

Now in his late thirties, Chuck (who asked that his real name not be used) works at the Pentagon, advising foreign militaries on defense and doling out millions of dollars in aid. As a GS-15, he’s paid at the highest grade the federal government offers and is proud of what he does. Over oysters at a Dupont Circle restaurant, he explains that programs like his provide stability in some of the world’s tensest regions and represent the United States’ spirit of “enlightened self-interest.”

Yet Chuck’s career has turned out differently than he expected when he hung the “Ask not” President’s picture on his wall. He has spent much of his energy navigating an immense, sclerotic bureaucracy that doesn’t always put human capital first. He has weathered furloughs and explained his reasons for staying put to friends outside his Pentagon bubble who dangle the possibility of making a lot more money in the private sector.

He wonders often if another generation will heed JFK’s call. “I’m worried,” he says, “about our ability to have bright, innovative young people.”

• • •

Fifty years ago, Kennedy rallied an army of young people to government service, then put them to work. Shortly after his election, he created his marquee initiative—the Peace Corps, which sent the nation’s youth to work in Latin America, Africa, and India for a modest wage—and put his brother-in-law Sargent Shriver in charge of it. The Peace Corps took off immediately, receiving more than 11,000 completed applications in the first few months. Those who didn’t go abroad were lured by Kennedy’s charisma and energy to join him in Washington. During his time in office, the ranks of executive-branch employees grew by more than 85,000.

“Kennedy tried to give people the idea that working for government was a higher calling,” recalls Priscilla McMillan, a former researcher for Kennedy who eventually left politics to become a journalist in Moscow.

Kennedy didn’t invent the notion of government service as duty of citizenship. “I went to the University of Virginia, where Thomas Jefferson said there is a debt of service from every man to his country,” says Mortimer Caplin, for whom the Public Service Center at UVA’s law school is named. Caplin taught law there to JFK’s younger brothers, Robert and Ted, in the 1950s. In 1961, he became commissioner of the Internal Revenue Service and brought the agency into the computer age, prompting Time to put him on its cover.

Now 97, Caplin still goes to his office at Caplin & Drysdale, the law firm on DC’s Thomas Circle where he has practiced since 1964. Wearing a trademark bow tie, he speaks jovially but deliberately, in a light Southern drawl, of the golden age of public service under Kennedy: “It was a privilege to be there.” He hardly has to add, “I don’t see much recognition of the significance of public service today.”

• • •

Precisely what changed from Caplin’s day to Chuck’s is easier to quantify than to explain.

Just a third of Americans have a favorable opinion of the federal government, according to a 2012 Pew Research Center poll, the lowest rating in the 15 years Pew has tracked it. Satisfaction and commitment among federal employees have also sunk to their lowest since 2003, says a report by the nonprofit Partnership for Public Service—to 60.8 on a 100-point scale. That’s 3.2 points below 2011’s measure, the largest drop ever. (Private-sector employee satisfaction remained constant last year, at 70.)

Americans’ view of their federal workforce has been in decline at least since 1980, with the election of a longtime standard-bearer of small government, Ronald Reagan. In his first hours as President, Reagan ordered a hiring freeze aimed at “stopping the drain on the economy by the public sector.” The theory that federal workers, besides contributing to the deficit, drag down private investment and hiring, has been echoed ever since, most recently by the Tea Party.

Andrew Biggs, former deputy commissioner at the Social Security Administration and now a scholar at the right-leaning American Enterprise Institute, points to the benefits and job security that are the hallmarks of a government job. “It’s tough to get fired in government, and that influences how people feel about public employees,” Biggs says. He has been a vocal critic of federal pay scales, saying federal workers could be paid 20 percent less. Asked how that might affect the talent pool, he says, “You could attract and retain the same workforce with lower benefits.”

Some government workers haven’t done much lately to burnish their colleagues’ image. Last year, the chief of the General Services Administration resigned hours ahead of the release of a report decrying the agency’s overspending, including an $832,000 conference boondoggle in Las Vegas where the entertainment included a clown and a mind reader. That scandal followed on the heels of “Muffingate,” in which senators lambasted Justice Department officials for paying $16 per baked good at a breakfast for law-enforcement personnel. The bill was later shown to be incorrect, but the story fit a common narrative of inefficiency, which employees say is ubiquitous and corrosive even within the bureaucracy itself. “The drumbeat of waste in government is demoralizing to most workers,” Chuck says.

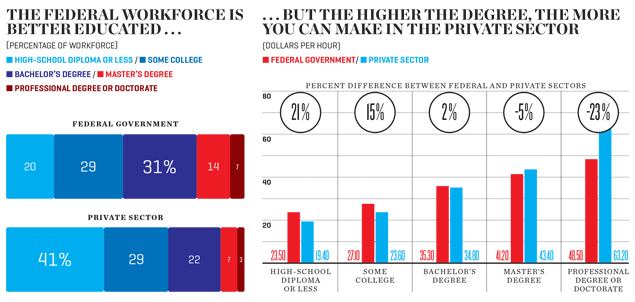

Waste, of course, is inevitable in a project as far-reaching as running the government. And while it’s true that public workers enjoy excellent benefits, budgetary constraints deprive them of simple amenities, such as free bottles of water, that are taken for granted in many workplaces. Moreover, although they’re well paid—the average full-time federal income surpasses $78,000—they’re also on the whole well trained and educated. Many could, and increasingly do, fetch higher salaries outside government.

• • •

Americans clearly want a lean and efficient government, but they want one ensuring that the air over our vast continent is clean, that our food and water are safe. Just as we may dislike cops until our house is broken into, we disparage federal workers until we need help paying our taxes or getting our government check. Then we expect a furloughed, penny-pinched IRS agent or Social Security Administration employee to pick up the other end of an 800-number call and help us out of a tangle. And by and large they do. It may be worth considering whether Americans are failing their public servants more than they’ve failed us.

That’s certainly the mood in many offices across the federal system. “You’re disrespected by members of [the] public every day because they don’t understand what you do and how you do it,” Ryan Gibson, a Customs and Border Protection officer in Detroit who monitors terrorists and drug traffickers at entry points along the Canadian border, told NPR in May. “They feel that we’re just there collecting a paycheck, not doing anything, and we have all these fringe benefits that we shouldn’t be entitled to.”

The furloughs brought on by the budgetary sequestration have further reduced efficiency. “It means there are [only] two or three days a week when everyone is in the office,” Chuck says. He has had trouble finding time for overseas trips to oversee the programs he manages. And Chuck’s problems may be the least of it. In August, the New York Times reported that the US trade representative could afford to send a negotiator to only one of 41 countries accused of violating American intellectual-property rights.

Is this what Kennedy envisioned when he made his plea for a selfless nation dedicated to public service?

President Obama was supposed to kick off a new, Kennedyesque youth movement. Obama’s popularity with the under-30 voters who swept him into office in 2008 promised to make government service sexy again, but the enthusiasm hasn’t been sustained.

Young people don’t see change coming from a broken political system. Rather, they look to “green” businesses or Silicon Valley; Google, not government, is the place to effect the revolution. National Journal’s Ron Fournier recently wrote in the Atlantic about his visit to Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government. In two days, he didn’t encounter a single student whose career goals included government service or elective office.

Crucially, the President’s critics say, Obama hasn’t projected himself as leader of the federal workforce, something critical for morale but also for making government work seem cool. Although in his opening months both the President and the First Lady visited an array of federal agencies as morale-boosting trips, those visits seem to have dried up amid the partisan rancor of the second term.

Max Stier, CEO of the Partnership for Public Service, says Obama—unlike his predecessor, George W. Bush—has never met collectively with the 7,000 members of the Senior Executive Service, representing the top government officials below the appointee level who set the tone for the 2.1 million career employees. “He’s lacked the recognition that his job is to actually run and manage the federal workforce,” says Stier, who served in the Clinton administration. (Obama’s letter to furloughed workers during the October shutdown assuring them they were nonetheless treasured may be too little, too late.)

Kennedy, by contrast, made history by being the first President to visit the IRS, a fact Mortimer Caplin is visibly proud of to this day. Priscilla McMillan remembers that Kennedy actually bore a mild contempt for the rank-and-file under him, but he never let it be known. “He would reach out to people within the bureaucracy,” she recalls.

Aaron (a pseudonym) is a thirtysomething with two Ivy League degrees who works at a top-tier agency on foreign aid. He feels his office is a place where his skills will never be rewarded, even if they’re recognized. “Managers are answering to bosses rather than cultivating talent, which is perhaps a function of short tenures in government at the political levels,” he says.

Other young government workers catalog similar complaints. They point to turf wars that prevent senior staffers from mentoring underlings because good ideas are often a zero-sum game: If someone else gets credit for smart thinking, you don’t. And no matter how many good ideas you have or implement, you probably won’t become the boss because that person’s position is an appointed one.

Aaron, who traveled to Iowa and Pennsylvania in 2008 to canvass for Obama, plans on giving notice in the next six months. He’s not sure where he’ll land, but the private sector is looking appealing.

Biggs isn’t surprised to hear that. He argues that the very nature of bureaucratic work is the biggest factor deterring future generations from considering a life of public service. “It’s not like it was in the Kennedy era when we had the Cold War and the Russians breathing down our necks,” Biggs says. “There were these huge, existential threats. We were putting a man on the moon. Now you take money from young people and give it to old people.”

He waves off the idea that current challenges, such as income inequality and climate change, will inspire the young: “It’s just not as exciting a time to be in government—resources are constrained. It’s why people are saying, ‘Ah, screw it. I’m going to just go make some money.’ ”

• • •

Between the defection of bright, talented “millennials” like Aaron—those born from the early ’80s to the early ’00s—and hiring freezes, the federal workforce is going gray. Stier points out that only 8 percent are millennials, compared with 25 percent of the private sector’s workers. And there’s some question whether the millennials we’re getting are the ones we want.

In many European countries, where the private sector offers few good options, the best students aspire to careers in the public sector. In the US, it’s a boon to everyone that our technology and financial companies are attracting our top graduates. But government needs talented new workers, even if we have vibrant private companies.

Kennedy’s legacy isn’t completely dead; it may just be changing, according to Patrick Hidalgo. One of five children of Cuban exiles, Hidalgo has a public-policy degree from the Kennedy School at Harvard and an MBA from MIT. In 2007 he joined the Obama campaign, went on to become a political appointee at the State Department, and most recently was named deputy director of the White House Business Council.

“It was this once-in-a-generation thing that you have a leader who inspires you,” says Hidalgo, 34. Notably absent in our conversation are mentions of Muffingate or pay freezes.

Yet the economics of public service for highly educated white-collar workers can be difficult. The disparity in pay between the White House and the law and lobbying firms in town—never mind Silicon Valley or Wall Street—is growing faster than ever. In the Kennedy era, a top official’s salary and a private-sector executive’s were not so far apart; now the difference can be in the hundreds of thousands or even millions. Law clerks leaving the Supreme Court today receive starting bonuses at law firms larger than the annual salary of the justices they helped.

Hidalgo admits that the economics of a public-sector salary are daunting for young people looking for upward mobility, or even for enough to pay their bills. His student-loan debt runs to six figures. “I don’t have the luxury of not worrying about a better economic future for me and my future family,” he says. Hidalgo’s story suggests that government work may soon be only for the financial elite who graduate without student debt or whose parents can help foot the bill of a career in public service.

Recently, Hidalgo left the White House to start two companies, one focused on emerging markets, the other on minority communities. He says it won’t be easy to make government work as appealing to the new generation of workers as the private sector is: “You just can’t make the government look like General Electric or Google.”

Hannah Seligson is the author of Mission: Adulthood: How the 20-Somethings of Today Are Transforming Work, Love, and Life.

This article appears in the November 2013 issue of The Washingtonian.