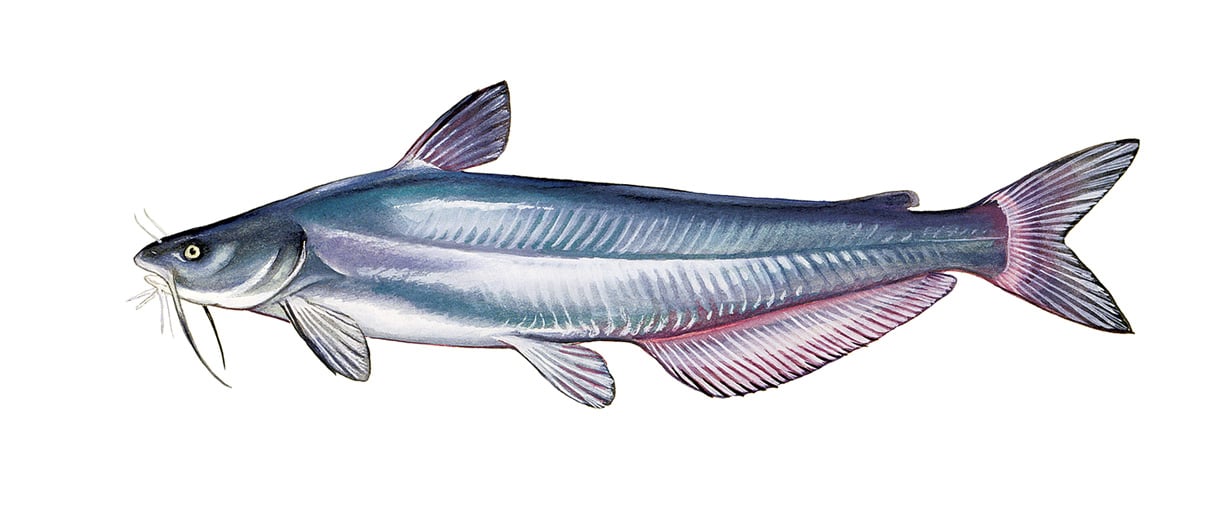

Maybe you’ve already seen blue catfish this spring at the fish counter in your grocery store, nestled on ice, and wondered: “That’s catfish?” Because blue catfish doesn’t look like catfish. For one thing, it’s actually pretty.

Blue catfish is a newcomer to Washington stores and restaurants, it’s sustainably caught in the Chesapeake Bay, and it’s probably tastier than any catfish you’ve ever had. That’s because unlike the farmed variety, which eat a diet of corn-and-soy feed, blue cats feed on medium-size fish like menhaden and white perch. Which is good for developing the fish’s flavor but bad for the bay’s delicate ecosystem.

Why haven’t we heard of it before? Because like many area residents, the fish relocated here. Native to the Mississippi, Missouri, and Ohio rivers (and sometimes called “chucklehead cat”), blue catfish was introduced to Virginia’s James, York, and Rappahannock rivers for sport fishing in the early 1970s. With no natural predators to threaten the species, it flourished, sometimes living up to 20 years and growing to 100 pounds. Now it’s invading the spawning waters of shad and other fish native to the bay’s tributaries, eating their eggs, and endangering their survival.

“It’s the greatest environmental threat the Chesapeake Bay has ever faced,” says Tim Sughrue of the supplier Congressional Seafood, in Jessup. Happily, there’s a tasty solution—to eat it.

Chefs around the country have led the way in popularizing other invasive fish such as snakehead and rainbow smelt, using consumer demand to help keep the fishes’ numbers in check. And in the past year, local chefs have embraced blue cat. You’ll see it in the superlative fish and chips at District Fishwife in Union Market and on the menus at Vidalia, Clyde’s, and Zaytinya.

Vidalia chef/owner Jeffrey Buben learned of the catfish from Sughrue. Buben’s first impression was that a fish caught wild from tidal waters sounded more appealing than farm-raised catfish, but he worried about its bigger size. “I wasn’t sure how it would affect taste profile and texture when they became larger fish,” he says. But a few tries—the fish is mild, clean-tasting, and flaky—convinced him it was worth putting on his menu, where it has stayed for the last year and a half.

In 2014, blue cat also started showing up in grocery stores. “Whole Foods was the first to jump onboard,” says Sughrue. MOM’s Organic Market started selling it earlier this year, too. Sughrue sold more than 800,000 pounds of wild blue catfish in 2014 and hopes to handle at least twice that much this year. Whole Foods spokesperson McKinzey Crossland says the chain’s fishmongers reported that people were at first put off by the name, but when stores offered samples, they started selling out. Bonus: It’s less expensive than comparable white fish like striper or pollock.

Blue cat comes off Jeff Buben’s grill moist, marinated lightly in lemon and a touch of licorice (click here for his recipe). Fiona Lewis, co-owner of District Fishwife, enjoys hers at home, baked with fresh herbs and a touch of lemon (click here for her recipe). Sughrue likes it pan-seared simply, with a pinch of salt, pepper, and a twist of lemon.

They might just be the tastiest ways to save the bay.

This article appears in our May 2015 issue of Washingtonian.