Here’s a quartet you don’t see every day: the American Civil Liberties Union, women’s health clinic Carafem, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, and right-wing performance artist Milo Yiannopoulos. But this unusual foursome is teaming up to sue the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority because they’ve all had advertisements rejected by the transit agency’s convoluted and inconsistent policies regarding political messaging.

“By rejecting a variety of advertisements submitted by Plaintiffs—ranging from an ad for an FDA-approved medication, to an ad urging a vegan diet, to an ad for a non-fiction book, to the text of the First Amendment itself—WMATA has violated Plaintiffs’ First and Fourteenth Amendment rights,” reads the complaint, which was filed Wednesday in federal court in DC. “And WMATA’s new advertising Guidelines, which explicitly or implicitly incorporate such viewpoint discrimination, are unconstitutional for the same reason.”

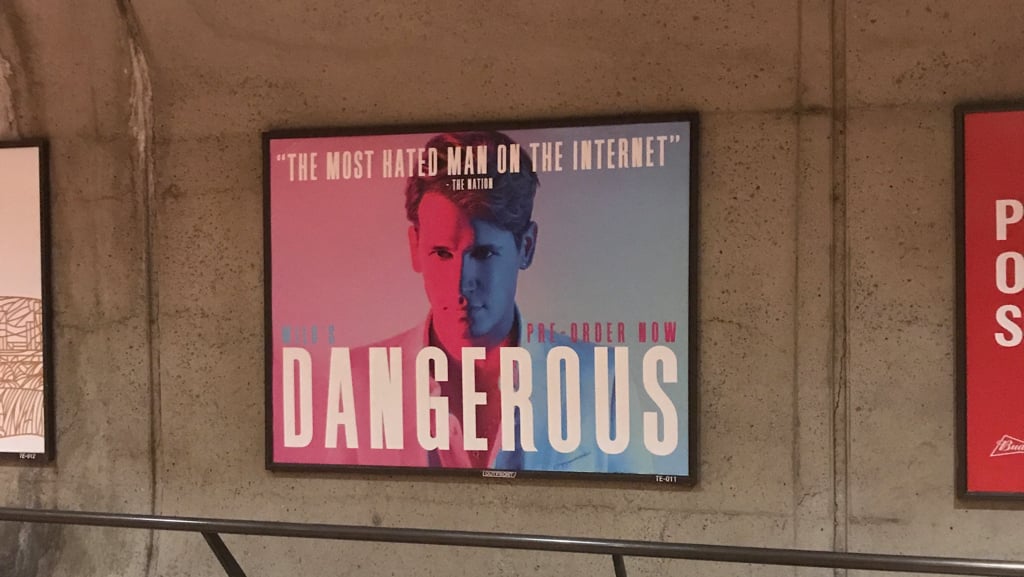

Metro pulled down advertisements for Yiannopoulos’s self-published book Dangerous on July 7 after complaints from riders who objected to the former Breitbart writer’s history of outlandish attacks of Islam, feminism, the Black Lives Matter movement, and individuals like the actress Leslie Jones. The ads themselves only displayed Yiannopoulos’s face, the title of his book, and a blurb describing him as “the most dangerous man on the internet.”

Metro pulled down the ads citing its guidelines against “issue-oriented” advertisements and messages “intended to influence public policy.” While ads on WMATA property are sold and managed by a third-party vendor, Outfront Media, the transit agency still reviews their content for compliance with its regulations. Milo Worldwide, the company Yiannopoulos established after being thrown out of Breitbart, had paid Outfront $27,690 for the placement and production of 45 ads around Metro’s system.

According to the complaint, WMATA initially told customers who complained that the ads for Dangerous were “consistent with Metro’s policy of remaining content-neutral when accepting advertising.” The transit agency reversed course a few days later. Outfront offered a refund, which Yiannopoulos rejected, saying it would be a violation of his First Amendment rights.

“The Milo Worldwide advertisements were rejected based on the identity of the author and/or the perceived viewpoint of the book or its author,” the complaint reads. “WMATA would have accepted, and would not subsequently have rejected, comparably-designed advertisements for books written by other authors. WMATA’s rejection of Milo Worldwide’s advertisement was based on considerations extrinsic to the advertisement, including the identity of the book’s author and his viewpoints on various issues.”

Notices for Yiannopoulos’s book were posted and remained up in New York’s and Chicago’s transit systems, both of which have rules against overtly political advertising.

But Metro’s regulations have tripped up more than just one objectionable writer. In January, Metro stopped Carafem from advertising that it prescribes pills that can terminate a pregnancy from up to ten weeks. Despite the fact that WMATA’s own guidelines that allow medical and health-related advertisements are acceptable “if the substance of the message is currently accepted by the American Medical Association and/or the Food and Drug Administration”—as mifepristone, the medication in question, is—Carafem’s proposed ad was rejected as political content.

A PETA ad was rejected last October after the animal-rights group wanted to post billboards depicting a pig alongside the text “I’m ME, not MEAT. See the individual. Go vegan.” Outfront told PETA the ad would be rejected for the phrase “Go Vegan” and that it did not contain any apparent “commercial value.” According to the complaint, Outfront suggested PETA add a solicitation for donations. WMATA ultimately rejected the ad a week later, telling PETA the proposed ad only served to oppose the food industry “without any commercial benefit” to the group. PETA later bought ad space on bus shelters in DC, which are controlled by the District Department of Transportation, not Metro.

The ACLU itself was also told earlier this year it ran afoul of Metro’s guidelines with a proposed advertisement that would’ve displayed the text of the First Amendment in English, Spanish, and Arabic; Outfront told the ACLU’s ad agency it was rejected because Metro “does not take any issue-oriented advertising.” A similar billboard went up in April in New York’s Times Square. And similar to PETA, the ACLU also resorted in DC to buying ad space in city-owned bus shelters.

“It is ironic that [Metro] wouldn’t post the First Amendment,” Arthur Spitzer, the ACLU’s lead attorney, says.”Transit advertising is a valuable venue for public communications, especially these days when people are more and more in their self-selected bubbles. If Metro was going to take down every ad where people didn’t like the author of a book or director of a movie or owner of a restaurant, where would that stop?”

Among other ads that Metro has accepted that Spitzer argues could be seen as objectionable are posters for the film Girls Trip and the play The Originalist, about the late Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia.

“Many viewers of the advertisement are aware that the play…contains many passages in which the Scalia character advocates his conservative judicial philosophy,” the complaint reads. “If the Milo Worldwide advertisements violate Guidelines 9 and 14″—referring to regulations Metro frequently cited in rejecting ads—”The Originalist advertisement also does so.”

The ACLU and the other plaintiffs are asking the judge to rule that Metro’s advertising guidelines are unconstitutional and that the rejected ads can go back up.

For his part, Yiannopoulos appears to acknowledge the oddity of him standing on the same side as groups he’s openly maligned in the past. “I’m glad that the ACLU has decided to stop aiding the spread of sharia law and their usual wrongheaded social-justice crusades to tackle a real civil rights issue,” he writes on Facebook. “I’m joined in this lawsuit by fellow plaintiffs including pharmaceutical villains and vitamin-deficient vegans, but I’m no stranger to odd bedfellows. Free speech isn’t about only supporting speech you agree with, it is about supporting all speech—especially the words of your enemies. Strong opponents keep us honest.

Read the complaint:

Wmata – Complaint by Benjamin Freed on Scribd