The Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority might have satisfied people who dislike Milo Yiannopoulos when it took down billboards advertising a book by the former Breitbart writer last week. But in classifying an ad for the book, Dangerous, as “intended to influence public policy,” Metro—for at least the second time in 2017—showed that it’s wildly inconsistent when it enforces its advertising guidelines.

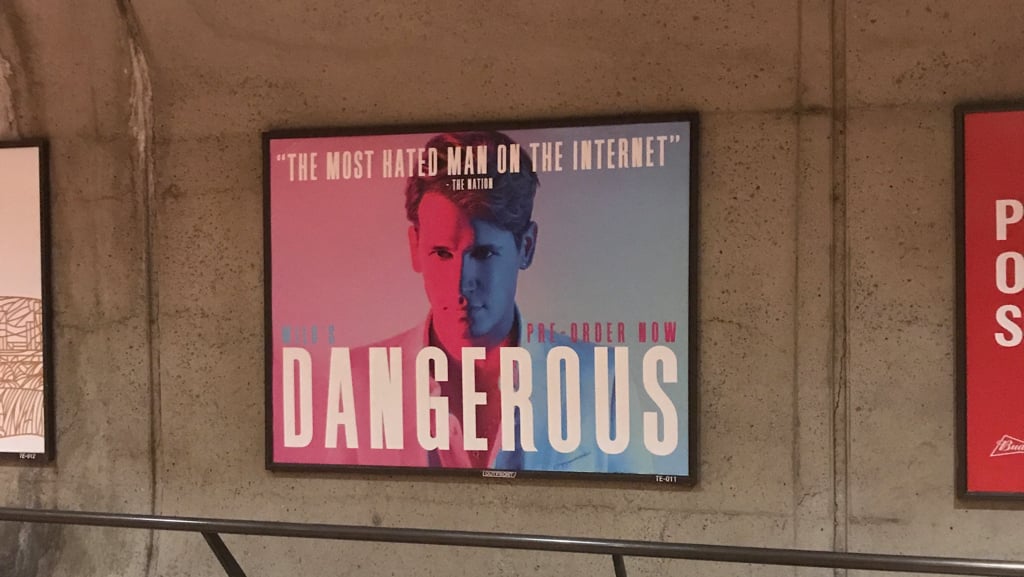

The ad in question was relatively simple: a photo of Yiannopoulos’s face, the book’s title, and a blurb from the Nation describing him as “the most hated man on the internet.” But the chapters from Yiannopoulos’s career that earned him that designation—ad-hominem insults of Muslims, women, and African-Americans; leading online harassment campaigns against specific people; and appearing to condone pedophilia—are absent. To the uninitiated, the ad seemed like any other for a book by an author trying to stoke his or her sales with whiffs of, well, danger.

I’d hazard to guess that—even with the hubbub surrounding his dismissal from Breitbart in February—Yiannopoulos is not a household name. But in DC, he was familiar enough that some people complained about his appearance on the walls of Metro stations, saying the ads violated the transit system’s rules regarding political advertisements.

Metro agreed and pulled the ads, which was, frankly, great for Yiannopoulos. His public identity is built around saying and doing things that are outlandish and offensive, then claiming to be a victim whose First Amendment rights were ripped away when people demand he get off the stage. He cried foul, for instance, when Twitter gave him the boot after he engineered a harassment campaign against the actress Leslie Jones.

But Metro’s removal of an ad for his book is not as cut-and-dry. The billboard, on its surface, was only marketing a product, not any of its author’s stated beliefs, however odious those might be. And this is where Metro appears to be enforcing its advertising guidelines rather haphazardly. (“We reviewed the ad, we found it violated our guidelines,” Metro spokesperson Richard Jordan told Washingtonian last week.)

“In this case, I think [Metro would] be hard-pressed to say this is political when there’s no political content and Metro regularly takes ads for books and movies,” says Ken Paulson, the president of the First Amendment Center. “Is Metro going to ban ads for Barack Obama‘s upcoming book?”

Metro adopted its current rules against political advertising in 2015 after the anti-Islam activist Pamela Geller attempted to buy space that would have displayed the winning artworks from a “Draw Muhammad” contest she held to challenge religious restrictions on creating images of the Muslim prophet. On its face, there’s nothing to stop a transit agency—or any other government-backed entity—from refusing advertising dollars from political actors. But the rules have to be applied consistently.

“The key to government regulation on speech in transit systems is to make sure regulations are applied across the board,” Paulson says.

That hasn’t been the case with Metro. Before the Yiannopoulos episode, Metro made a mess for itself in January when it blocked Carafem, a Chevy Chase women’s health clinic, from advertising that it offers prescriptions for pills that will terminate a pregnancy at up to ten weeks. The proposed ad only featured the pill’s availability, not any statements advocating reproductive rights. But the campaign was nixed because it was determined by someone at Metro to be “issue-oriented,” even though it comported with the guideline on ads for medical services, which reads: “Medical and health-related messages will be accepted only from government health organizations, or if the substance of the message is currently accepted by the American Medical Association and/or the Food and Drug Administration.” The pharmaceutical in question, mifepristone, is approved by the FDA.

“If you want to get rid of abortion services, then you have to get rid of all medical services,” he says.

Yiannopoulos isn’t the only political irritant to raise a beef with Metro over its ad policies. Over the weekend, I received an email from Mark Weber, the director of a Holocaust-denial group called the Institute for Historical Review, in which he wrote that he had purchased ad space only for his ads to be rejected for the same reasons Metro cited in striking down the displays for Yiannopoulos’s book. Weber’s proposed ad blared the slogan “History Matters” against a globe, accompanied by his group’s name and website, which is full of numerous articles espousing Holocaust revisionism and anti-Semitic viewpoints.

The Institute for Historical Review’s lawyer wrote back to Metro that its slogan would not have sparked any objection “if it had come from the Smithsonian Institution or the faculty of the Georgetown University History Department.” And Paulson says that absent context, the wording “history matters” does not constitute a “blatantly political statement.” But contra Weber, that does not make WMATA’s refusal to run the ad flimsier than its decision to take down Yiannopoulos’s billboards.

“That’s a much closer call than the Milo ad,” he says. “If you’re sitting on the bus and you type in that URL you’re completing that ad.”

Beyond questions advocacy or good taste, though, Metro’s bigger advertising problem appears to stem from the wording of the guideline it has cited in refusing Carafem, Yiannopoulos, and Holocaust deniers. “Advertisements intended to influence members of the public regarding an issue on which there are varying opinions are prohibited,” the rule reads. Taken most broadly, that could include just about everything featured in ads placed around Metro, from spots featuring defense contractors—there are a lot of people who don’t like war—to promotions for fast-food restaurants, energy drinks, and critically divisive movies.

“[Metro] need[s] to go back and read what they wrote,” Paulson says. “The key is they just need to write it more carefully.”