Virginia Attorney General Mark Herring said in a statement Friday that couples applying for marriage licenses no longer have to list their race on state forms, the Richmond Times-Dispatch reported. The news comes after three Virginia couples who refused to provide their race were denied licenses, then sued Virginia on September 5 to challenge the constitutionality of the “records of marriages” law.

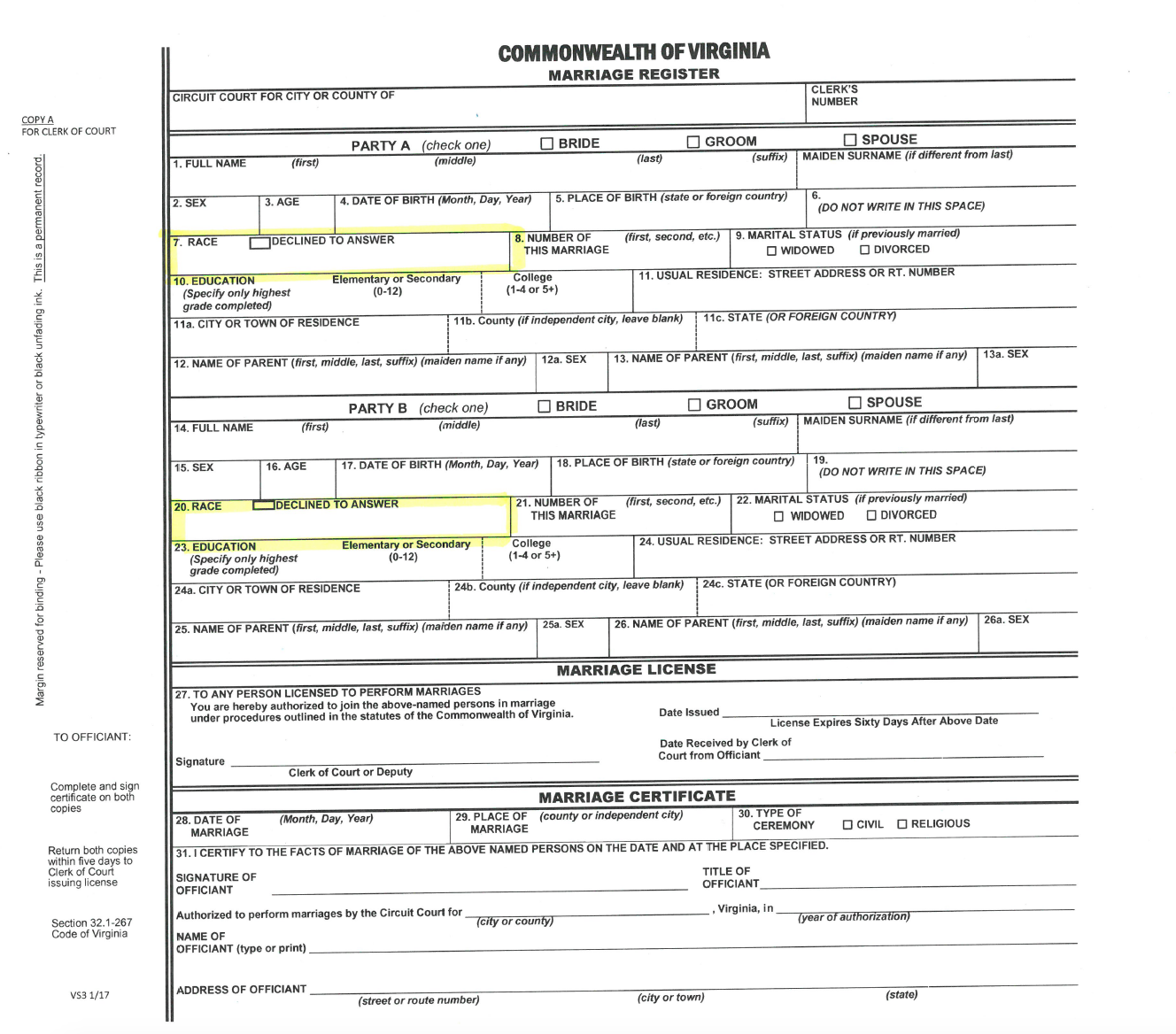

In response, the state amended the application to include the option, “Declined to Answer.” In a memo sent to director and state registrar Janet Rainey, Herring concluded that “a couple may decline to provide an answer about race, and an officer issuing a marriage license may accept a marriage license from a couple who declines to answer a question about race.”

In a statement provided to Washingtonian by a spokesperson, Herring said, “We were happy to help quickly resolve this issue and get these couples what they asked for. These changes will ensure that no Virginian will be forced to label themselves in order to get married. I appreciate the courage these couples showed in raising this issue, and I wish them all the best in their lives together.”

But Victor M. Glasberg, the Alexandria civil rights attorney who represents the couples that filed the lawsuit, says Herring’s decision is “insufficient”—the law still stands, and the updated form does not guarantee that the code won’t be interpreted differently by a successor attorney general. Although they can now receive marriage licenses, the couples plan to move forward with the litigation.

On Monday, in response to Herring’s statement, Glasberg filed a motion for summary judgement on behalf of the plaintiffs. A hearing is scheduled on October 4 before U.S. District Judge Rossie D. Alston Jr. to address their claim that the law is unconstitutional. “The provision at issue deserves a rapid mercy killing,” the plaintiffs allege. “It is insufficient for the racial identification inquiry to remain but be labeled as ‘optional.’ Virginia could just as well re-institute separate water foundations for ‘white’ and ‘colored’ but mark the designations as ‘optional.'”

In the late 1970s, Glasberg worked for Philip Hirschkop—the attorney who represented the Lovings in the landmark Loving v. Virginia case of 1967 in which the Supreme Court struck down the ban on interracial marriage—before starting his own practice in 1982.

One couple involved in the lawsuit, Sophie Rogers and Brandyn Churchill, filed for a marriage license in the Rockbridge County circuit court and were given a list of 230 options—including outdated and offensive terms like “Mulatto,” “Quadroon,” “Octoroon,” “Aryan,” and “White American.” Glasberg says the Virginia marriage license law is tied to a racist history that goes back centuries and, as he writes in the 31-page complaint, the “Virginia Racial Integrity Act of 1924, was originally called “An Act to Preserve the Integrity of the White Race.” Virginia is one of eight states that still require a record of the applicants’ race.

“I don’t think there’s any question that it’s racist,” he says. “The notion is that calling something a ‘race’ is extraneous. It doesn’t add anything. And so you can ask, ‘Oh, so you’re just talking about a word?’ Yeah, we’re talking about a word. But words are important. Words are dramatically important in terms of how people understand themselves and how they understand the concept of otherness.”

At least one Virginia delegate plans to bring this fight to the General Assembly in January. Mark Levine, D-Alexandria, says regardless of how the hearing goes, he will introduce a bill to remove race from the code when the legislature reconvenes next year. Race, he says, is an arbitrary concept and is as useless to record on marriage licenses as hair color or height. “This question has a long, storied, and ugly history,” Levine says. “Racial classification has, for the most part, been used to harm people. To the extent that we want statistics in order to help historically persecuted people, that is a legitimate purpose, and we have the census to do that. But people have a right to privacy and should never be compelled to state their race.”

Levine says the bill will be simple—to remove two words (“and race”) from the law requiring age and race to be recorded for marriage licenses in the Commonwealth. As the Times-Dispatch reported, the code has been changed before, by one of Levine’s predecessors, no less. In 2003, Marian Van Landingham, D-Alexandria, sponsored a bill to remove the provision, but two years later, it was brought back by the late Republican delegate Harry Blevins.

Levine is confident the legislation will pass in the state House and Senate. “I don’t see why this bill can’t pass unanimously,” he says. “This should be an easy lift, but we’ll see.”