The main thing to know about urban music: Washington is both the cradle and the capital of go-go. It was born here, was bred here, and has continued to thrive here for more than 25 years.

Yet mention this to people who don’t listen to go-go and you’ll probably get a response like, “Go-go? Heard of it. Don’t know a thing about it.”

Even people who don’t like country music can name a few twanging tunes and bands–maybe more than they’d like to admit. But go-go exists in a self-segregated world of black and white Washingtonians who know almost everything about it or nothing at all.

Maybe more than any other musical genre, go-go must be experienced live to be appreciated. That stands to reason: Go-go began as a form of live house music meant to keep an uninterrupted, down-home groove going on the dance floor. Add in the back-and-forth between band and crowd–reminiscent of the call-and-response in many African-American church sermons–and you get an immediate, communal feeling that binds everyone together in a funky, syncopated here and now.

“You get totally involved with the audience,” says Chuck Brown, the charismatic founding father of go-go. “You get ideas from them all the time, like when they shout out little hook lines, and you put ’em into the groove.” Or as Charles Stephenson, a former go-go band manager and coauthor of The Beat: Go-Go’s Fusion of Funk and Hip-Hop, puts it, “The audience is another instrument for go-go bands.”

Brown realized that early on. By the early 1970s he was already a veteran of the DC club scene, playing three or four dozen Top 40 covers a night to crowds that were slow to get on their feet. “They’d come in all dressed nice and sit down at their tables and then not get up till they were drunk,” he recalls. It didn’t help that the songs lasted only two or three minutes each; any dance-floor momentum stopped dead while the band geared up for the next tune.

So Brown hit on the idea of using a running percussion beat to tie all the songs together, making a set sound like a medley of individual numbers starting and stopping over a pounding, nonstop rhythm. “We started breaking the tunes down and talking to people at the same time, and rhyming with them, and then neckties would come off and the floors would get packed right away.”

Brown called it go-go for two reasons. It was the era of “go-go clubs and go-go girls, but there was no go-go music.” The other reason: “Once the energy got going with this stuff, it just kept going.”

After a few more years of doing covers, Brown started writing his own songs. His first hit was “Bustin’ Loose,” recorded and released in the late ’70s.

Along with Brown and his group, three other early go-go bands–Trouble Funk, Rare Essence, and Experience Unlimited (EU for short)–defined and refined stylistic variations. “EU always had a screamin’ lead guitar player in the lineup, and that enabled it to do more rock-sounding go-go,” says Stephenson, EU’s first manager. “Trouble was always a heavy funk band, and Rare Essence was more R&B.”

Go-go is still big in DC, but its heyday was in the 1980s. EU had a ride in the national spotlight when Spike Lee used one of its tunes, “Da Butt,” in his 1988 film School Daze. Trouble Funk played the prestigious Montreux Jazz Festival in 1986. Both bands regroup to perform periodically, sometimes with most of the original members, other times with new players.

Of all the first-generation go-go bands, Rare Essence has proven the most durable. “Rare Essence is very adept at knowing how to change their material based on their audience,” says Stephenson. “As their audience has gotten younger or older, they make the necessary adjustments.”

The group’s many changes over the last 20 years have helped it achieve a rare versatility. Classic, old-school go-go is a mix of funk, jazz, blues, and soul built on that seductive, nonstop beat. Unlike its cousin, hip-hop, which developed in New York around the same time, go-go features a full band, typically including guitars, bass, and, most important, horns.

“Back in the old days,” Brown says, “if you didn’t have horns, you weren’t a complete band.” The presence of a horn section is probably the greatest difference between old-school go-go groups and newer ones, which are influenced by hip-hop’s stripped-down rhythms and cadences.

“Rare Essence can do both new-style go-go or old-school,” says Kevin “Kato” Hammond, who runs a Web site (www.tmottgogo.com) chronicling DC’s go-go scene.

Some prominent new-style go-go bands are 911, Raw Image, Backyard, Lissen, Junkyard, Suttle Thoughts, and Uncalled 4. All perform original material, but don’t be surprised to hear the odd cover or two. “The market really likes go-go-style covers of pop songs,” says Kevin “Fudj” Bright, who plays keyboards for a group called MVP.

A group just beginning to draw attention is Fatal Attraction, whose oldest member is 19. “These guys are going against the grain of younger go-go bands that do all this jumping and yelling and pounding,” says Hammond. “They’re doing more old-school flavor, and they’ve even got a horn section. They remind me of Rare Essence when they started.”

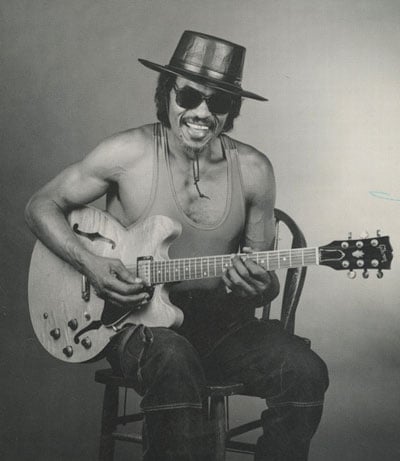

Go-go’s Godfather

“The thing about go-go is you don’t have to be a great musician to play it. All you got to do is have good rhythm and a good concept of audience participation, of knowing what the people like.” So says Chuck Brown, go-go’s daddy, who has rhythm that can make the dead dance and an uncanny concept of audience participation.

After leaving home and school at the ripe age of 13, Brown eventually found himself doing a stretch in Lorton prison. There, he has said, he learned to turn his life around, earning a high-school diploma while practicing guitar. After his release he played music, working his way up from house parties to clubs.

As early as 1966 Brown was beginning to develop the go-go sound and beat, but it took another ten years to find all the right pieces and the right way to integrate them. Now in his mid-sixties, Brown is pretty much an icon of the DC music scene, but his shows continue to draw big crowds as if he were still the new, hot thing.

Homegrown go-go tends to overshadow other styles of urban music in Washington. Hip-hop, which accounts for 11 percent of record sales nationwide, barely registers on DC’s radar. In fact, when some of the early hip-hop groups came to town, “those rappers got their heads handed to ’em a lot of times because everybody here wanted go-go,” says Stephenson. Not much has changed. “So many talented [hip-hop artists] here don’t get a chance to be heard because go-go is so big,” says Bright.

Area hip-hop acts include Head Roc, Infinite Loop, Opus Akoben, Unspoken Heard, Poem-Cees, Defined Print, and 3LG. So far no local groups have won national attention, but several insiders think Defined Print has the potential. A promising young performer from Oxon Hill calls himself Storm the Unpredictable [see “Storm Alert”]. Says Kato Hammond, “Storm’s about to blow up big.”

Looking for reggae? According to Dera Tompkins, an independent promoter and member of the Washington Area Music Association board, “The scene was blossoming a lot more some years ago when we had significant groups like Black Sheep and Third Eye. But time passes, people have to work, get jobs, move–things change.” Still, some 20 reggae bands play regularly in the Baltimore-Washington area, she says.

Tompkins, who organizes an annual tribute show in Washington to reggae’s main icon, the late Bob Marley, also notes a difference between the reggae of Marley’s generation and that of today. Roots reggae, as she calls it, “was kind of political, and it was about consciousness-raising. Now it’s dance-hall music. It’s all based on rhythm to get you moving, and the lyrics are very different.” Washington reggae bands playing regularly include Meleket, DKGB, Strykers’ Posse, Jah Works, Culture Shock, and Soldiers of Jah Army.

There’s a fair amount of neo-soul in the city, but like hip-hop, its profile is relatively low. The genre–“a kind of soulful, instrumental, singer and spoken-word concept,” as Tompkins describes it–is rooted mostly in the U Street area of Northwest DC. Its two most visible figures are W. Ellington Felton, a poet, and singer Raheem DeVaughn and their respective groups, Art!Hurts and Urban Ave 31. You can catch them, along with a mix of other urban artists and musicians, at a semiregular downtown event called Groove Gumbo. Date and location are usually announced by e-mail (groovegumbo@onebox.com) and word of mouth; the last few have been held at Five, a club south of Dupont Circle.

Mya Harrison, who performs using her first name only, hails from Landover, but she is already known coast-to-coast as a rising young star of the new R&B and soul. Still in her early twenties, she’s already netted two Grammy nominations, and all signs point to a strong career ahead.

Depending on your definition of world music, it is and isn’t here. To some, world music is everything that isn’t R&B. To others, it’s music with roots in the Third World. Still others believe that if it doesn’t have some kind of specific Latin sound or influence, it isn’t world music. Last year’s Wammie awards had a separate category for world music, with well over a dozen different bands and artists nominated. Probably the best known of Washington’s world-music groups is Shahin & Sepehr, a duo with a flair for pop tunes and melodies evoked through Spanish guitar, keyboards, and timpani.

Whatever your taste in urban music, Washington has its own street rhythms and sounds. Check them out. You may be surprised by what you hear–and learn.

This article appears in the February 2003 issue of The Washingtonian.