The Obama/Biden ticket is historic, but among my fellow constitutional-law professors, it has a special cachet: This is the first time that two constitutional-law professors have been elected president and vice president. Obama was a senior lecturer at the University of Chicago Law School from 1996 to 2004, and Biden has been an adjunct professor at Widener University School of Law since 1991.

How does a constitutional-law professor who has been elected president approach the job? And do former law professors bring different perspectives and qualities of mind to the presidency than do a nuclear engineer such as Jimmy Carter or a business-school graduate such as George W. Bush?

Before Obama, three other constitutional-law professors have gone on to be elected president: William Howard Taft, who was a professor and dean at the University of Cincinnati Law School and, after leaving the presidency, taught at Yale Law School and then served as Chief Justice of the United States; Woodrow Wilson, who was a professor of jurisprudence and president of Princeton as well as the first lecturer in constitutional law at New York Law School; and Bill Clinton, who taught constitutional law at the University of Arkansas.

“Not all of them did a great job, but all of them really understood government and issues involving separation of powers,” says presidential historian Michael Gerhardt, who teaches at the University of North Carolina Law School.

When they ran against each other in 1912, Taft and Wilson treated the nation to an all-constitutional-law campaign, with Taft championing a radically limited view of federal power and Wilson arguing for a more energetic executive.

As a law professor, Wilson had exalted Congress as the most important branch of the federal government, but during and after the election campaign—no surprise—he discovered the virtues of presidential leadership.

The mixed success of Taft, Wilson, and Clinton suggests that a pragmatic temperament is more important than ideology in determining a former professor’s success as president. “Taft was a better constitutional-law professor than president, and I’m not sure there isn’t a direct connection between those facts,” says presidential historian Richard Norton Smith. “Taft was one of the few presidents who ever wrote a book about the philosophy of government, which suggests that he lacked the pragmatism of a great politician.”

Wilson had notable legislative successes in his first term—creating the Federal Trade Commission and the Federal Reserve—but was undone by his ideological inflexibility. “The bad Woodrow was stubborn to the point of self-destruction, saw compromise as surrender and moderation as weakness, and strangled his own baby, the League of Nations, in the cradle,” says Smith.

As for Clinton, his brief stint as a law professor from 1973 to 1976 may have contributed to an enthusiasm for ideas and a wonkish engagement in policy debates that led to some of his legislative successes, such as free trade and welfare reform. But his lack of discipline in playing with ideas also led to late-night bull sessions with aides that created the impression of disorganization and lack of focus—just like debates in a law-school faculty lounge.

Is Obama likely to be a constitutional ideologue like Taft and Wilson or a pragmatic if undisciplined policy wonk like Clinton? Or might he move into an even higher category of the most successful presidents, with Lincoln and FDR? His performance as a teacher at the University of Chicago may provide some clues.

When the New York Times published the model answers Obama had drafted to his constitutional-law exams in the 1990s, my immediate reaction was one of professional respect: The care and precision with which Obama sketched out the competing constitutional arguments on such questions as human cloning and affirmative action put many of my colleagues and me to shame.

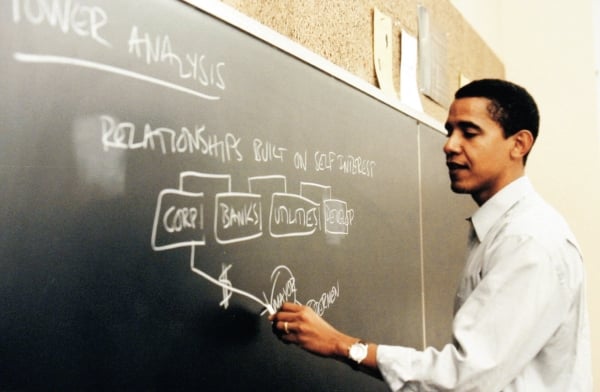

Former colleagues of Obama’s at the University of Chicago confirm that the future president, in the classroom, was more interested in provoking a conversation among people of different political perspectives than in imposing his own ideological views. “He was off-the-charts popular with students, and there was very little complaint about his being ideological or cramming points of views down their throats—and our students are pretty conservative,” says David Strauss, a constitutional-law professor there.

In Obama’s second book, The Audacity of Hope, he made clear that he believes constitutional values should be shaped by political activism from the ground up rather than simply imposed by judges from the top down. And his experience as a law professor seems to have confirmed his view that courts have seldom been the primary engine of social change in America.

“Changing the path of the Supreme Court will not be a high priority of his,” says Strauss. “He won’t be like a President Roosevelt or Reagan or Bush who had ideological agendas for the court, because he thinks about political change more like a community organizer.”

Instead of relying on judges to enact his agenda, Obama’s training as a law professor suggests that he will be personally engaged in shaping the legal arguments that define his administration—on questions involving civil liberties, civil rights, and the “war on terror.”

Cass Sunstein, an Obama adviser and former colleague at the University of Chicago Law School, told me last winter about a phone call with Obama after Sunstein suggested President Bush’s terrorist-surveillance program might possibly be legal.

As the two discussed whether the President had the authority to conduct warrantless wiretapping, Obama noted that the Supreme Court had never endorsed the view that a president has inherent authority to act. He also noted that the vague congressional authorization that Bush invoked may well have been barred by the earlier, and more specific, Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act. Sunstein recalls saying at this point in the debate, “Yes, sir!”

Unlike President Bush, the business-school graduate, who delegated his legal policy-making to advisers who took radically expansive positions about executive power in his name, Obama is able to discuss constitutional issues with a precision rivaled only by our most constitutionally sophisticated president, Abraham Lincoln.

As a result, Obama is likely to articulate constitutional positions and then conform his presidential actions to them rather than take positions and then rely on lawyers to justify them.

Lawyerly caution, of course, can be an impediment to inspirational political leadership: During the primary campaign, Obama was criticized for being too nuanced and cerebral in debates with Hillary Clinton, who was praised for her boldness in answering questions about the war on terror. But doubts about Obama’s ability to inspire faded as the campaign progressed, and by the end, some were comparing his rhetorical skills to those of Lincoln.

Our greatest president, Lincoln was also a great constitutional lawyer, even though he was self-taught. But it wasn’t Lincoln’s legal precision that was the key to his greatness; it was his command of language. Lincoln had a gift for making complicated ideas accessible without simplifying them, and this helped him lead the nation during its most divisive struggle by articulating political arguments in constitutional terms that citizens of very different views could understand and accept.

Obama also seems to have this rhetorical skill, and his experience as a law professor may have helped him hone it. “Obama has a remarkable ability to frame complex ideas in a way that can appeal to broad audiences,” says Michael Gerhardt. “It’s something constitutional-law professors have to do, but Obama has taken it to an unprecedented level.”

It is now a truism that, as the presidential historian Richard Neustadt noted in 1960, presidential power is the power to persuade. Jimmy Carter’s background as a nuclear engineer and George W. Bush’s background as a business executive may have contributed to the fact that they were more interested in issuing orders than in persuading citizens who disagreed with them.

Obama’s even temperament is likely to matter more than his background as a constitutional-law professor in determining whether he can follow through on his promise to bring together red and blue America into the United States of America. Nevertheless, those of us who try to conduct constitutional conversations among students of different perspectives in the classroom will be following his progress with special interest.

At the very least, Obama has given the lie to the old saying that “those who can, do; those who can’t, teach.” It turns out that those who teach can also do a lot.