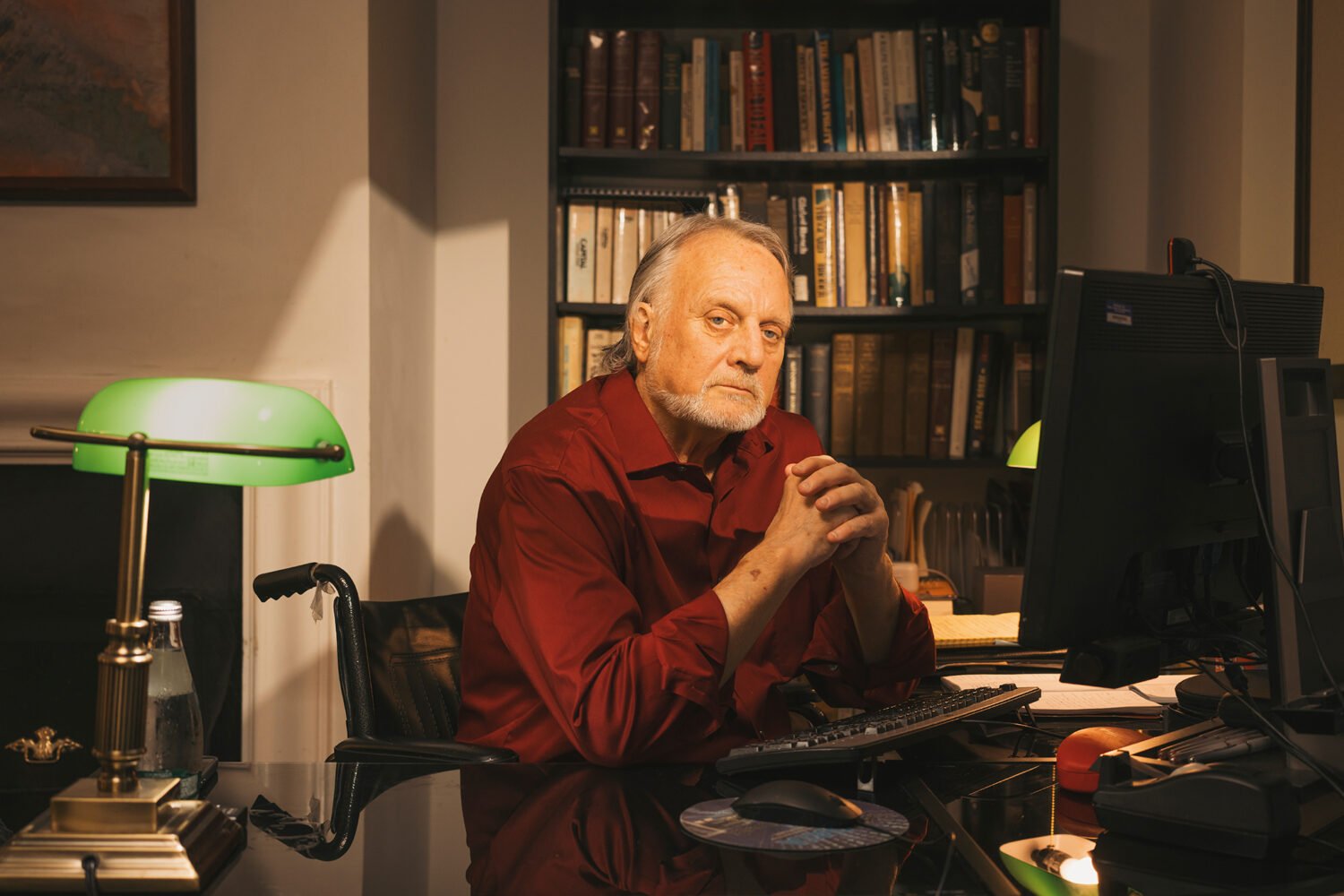

Michelle Thomas, an assistant US Attorney for the District of Columbia, approaches the witness stand. She has a lot on her mind, but her concentration appears absolute.

Thomas recently returned to work after being so sick and sleep-deprived that she slept for 31 hours—getting up only once for some apple juice. Doctors have been running tests, and the results are troubling. They show that Thomas’s blood-cell counts are out of whack.

The doctors say she might feel better if she can get more rest. But her intense workload and the disturbing details of her cases have made sleep even more elusive than usual for the self-proclaimed insomniac.

At the moment, she doesn’t have the luxury of dwelling on any of this. Her only objective is to get justice for the US government and the young woman—whom we’ll call Lisa—allegedly assaulted by the defendant.

Thomas is facing the defendant now. He’s claiming that he merely reached over his girlfriend Lisa’s lap to retrieve a cell phone while they were in her car, that there was a struggle over the phone, and that in the process he may have accidentally grazed her face. He denies he intentionally hit her, yet the photo of Lisa after the incident shows her with a split lip and scratches.

Thomas begins to fire away at the witness box in courtroom 215 of DC Superior Court’s Moultrie Courthouse. It’s established that the defendant and the victim are nearly the same height. Thomas then asks the man to demonstrate how far away from the steering wheel Lisa was sitting. He shows that she was close to the wheel, sitting upright.

As the line of questioning continues, Thomas’s intentions become apparent. She’s showing the judge that Lisa is tall and has good posture. Her boyfriend’s hand would have been much lower than her jaw line if he was only reaching across her lap, thus making it unlikely he could have accidentally made contact with her face.

Thomas didn’t lay eyes on either Lisa or the defendant until about five minutes before the trial began. Thomas was handling another matter in a different courtroom when another assistant prosecutor rushed in and asked her to try the case. No one else was around to do it.

“I said I could do it in 30 minutes,” Thomas recalls. “They said, ‘Now.’ ”

It’s April 1, 2010, and Thomas has been a prosecutor in the District for six months—a short time in most professions, but among those assigned to the fast-paced misdemeanor division in the DC US Attorney’s Office, she’s a veteran, already having handled dozens of cases like this one.

As she chatted with Lisa on the escalator ride up to the second-floor courtroom, Thomas, who is also tall, noted Lisa’s height—“She’s eye to eye with me”—and determined that it could be advantageous at trial.

An hour later, it appears her quick thinking was enough. Judge Herbert Dixon finds the defendant guilty. (The case is a misdemeanor bench trial decided by a judge. While the majority of felonies are decided by a jury, most misdemeanors are not.) Dixon gives the young man ten days in jail and two years of supervised probation.

It’s time for the next case.

Thomas’s office, the US Attorney’s Office for the District of Columbia, handles some of the country’s highest-profile matters. In the past year, prosecutors there have dealt with headline-grabbing cases involving Somali pirates, alleged Taliban leaders, and an embattled former baseball star.

But most of the work is less splashy. While the office prosecuted 425 federal cases in 2009, it also prosecuted about 20,000 cases involving local crimes in DC Superior Court—the drug crimes, prostitution cases, thefts, assaults, gun-related offenses, domestic-violence matters, and sex offenses that affect local neighborhoods. Of those, 14,000 were misdemeanors.

Most of these matters are handled by prosecutors in their first year or two in the office. Many are barely out of law school, and most have never tried their own cases before. From the get-go, the attorneys assigned to misdemeanors are handed a portfolio of about 100 cases each that they’re responsible for preparing.

For these lawyers, a relatively light day might mean 12 hours spent between the office and DC Superior Court, and weekends are devoted to trial prep. It’s more of a lifestyle than a job.

Yet the office attracts a very competitive pool of applicants. In 2009, nearly 2,000 lawyers applied, including former Supreme Court clerks, associates from top law firms, and graduates of the nation’s best law schools. The starting salary for prosecutors with three years of prior legal experience is less than $60,000, a third of what they could take home at most top law firms.

Some are attracted to the public-service aspect, but others want the job because no other legal position offers the breadth of experience available to a lawyer in the DC US Attorney’s Office, where cases range from marijuana possession to matters of national security. Many of the city’s best trial lawyers first learned how to work a courtroom as prosecutors in the DC office.

With more than 320 attorneys, DC has the largest federal prosecutor’s office in the nation. Like the offices of the 93 other US Attorneys around the country, it’s funded and overseen by the Department of Justice, but the District’s office is the only one that prosecutes local crimes in addition to federal crimes. A prosecutor starting out in another US Attorney’s Office may be assigned to a federal investigation that takes months to get to trial, but a prosecutor in DC might wind up trying a misdemeanor the first day after training.

As the prosecutors advance through the office, they get to try federal cases as well. But the first hurdle is to make it through the grind of DC Superior Court.

That journey isn’t easy.

In the fall of 2009, three of the new class of assistant US Attorneys agreed to let The Washingtonian follow them through their first year on the job. Each took a very different path to becoming a prosecutor; each would have a very different experience.

AUTUMN: A CHANCE TO BE A REAL LAWYER

There’s no pomp and circumstance about this room at the US Attorney’s Office, just off the Judiciary Square Metro stop, as Channing Phillips—a striking man with salt-and-pepper hair—takes the podium. Ceiling fans whir overhead, and fluorescent lights cast an unflattering glow.

But this fall day in 2009 is a momentous occasion: Phillips, the acting US Attorney, is about to swear in a group of new assistant US Attorneys—also known as AUSAs, or line assistants.

“For many of you, this day has been a long time coming,” Phillips tells the ten prosecutors joining his team. He acknowledges that some of the family members in attendance may be wondering why their loved ones signed up for this: “Clearly, it wasn’t for the salary. It will be the look from that family member or victim that will make it all worth it.”

They all line up and take their oath. Then each new AUSA gets a photo taken with Phillips.

In total, 29 new line assistants were sworn in last year at the DC office—most hired by then–US Attorney Jeffrey Taylor, a George W. Bush appointee. When Taylor resigned after President Barack Obama took office, it fell to Phillips, a career prosecutor, to keep the office running until Obama’s pick for the job, Ronald Machen, started in February 2010.

To get here, the new line assistants had to survive a rigorous interview process. Applicants start with three hourlong interviews, each with a different senior assistant prosecutor. Generally, if two of the three vote them qualified, they move on to a second interview and a videotaped opening statement.

“They grilled me,” recalls Thomas of her second interview. “You know how you’re always sitting up proper in an interview? I had to lean back. I exhaled and was like, ‘Okay, bring it on.’ ”

The panel rapid-fires questions: “Why do you want this job?” “Is that really your answer?” “Do you know how hard you’ll have to work?”

For Thomas, who is in her mid-thirties, becoming an AUSA was a second career. The Oakland native had earned a finance degree from California State University at Fresno and an MBA from the University of California at Berkeley and had worked in financial services. She was an executive at the Gap’s San Francisco headquarters when she had an epiphany: I’m not saving the world—I’m clothing the world. And not even the world, just rich people who can afford a $32 T-shirt!

She then founded and ran a nonprofit devoted to promoting diversity within business schools and helping minority MBAs network.

She started at Howard University School of Law thinking her degree would be useful in a business career, but criminal law quickly became her passion. Yet she nearly missed the chance to become a prosecutor.

Thomas had a plan after graduation—an offer from the high-end law firm Morrison & Foerster in San Francisco, which would bring her back to her family in the Bay Area, and an offer to clerk beforehand for a judge her first year out of school. The firm would pay $175,000 plus a $50,000 bonus for the year she spent clerking. But the best-laid plans can go awry, and Thomas’s did during her clerkship as she watched President-elect Obama speak on inauguration weekend about the importance of community service. He quoted Martin Luther King Jr.: “Everybody can be great because everybody can serve.”

This was her chance to have an impact. She applied to the US Attorney’s Office the day of the deadline.

After the second interview, prospective prosecutors are handed a set of facts from a case they’ve never seen, given an hour to review them, and then told to present an opening statement while being taped. This phase has brought some interviewees to tears and caused others to walk out.

It’s meant to test whether they can handle a situation like the one Thomas was in when she tried the case against Lisa’s boyfriend five minutes after first seeing it.

“It does tend to put the fear of God in them,” says Jeffrey Taylor, the US Attorney who hired much of the 2009 class that Channing Phillips later swore in.

Even if a candidate survives the opening statement, it’s not over. The last step is a meeting with the US Attorney, who has the final say about whether a candidate is qualified. Taylor liked Thomas, and soon she was calling Morrison & Foerster to reject the firm’s offer. Her first assignment when she started in September 2009 was the misdemeanors caseload in the sex-offense-and-domestic-violence section.

Taylor—who now works at Ernst & Young advising companies on regulatory compliance and fraud issues—says that when he was hiring line assistants, he was looking for attorneys who were passionate about becoming prosecutors but who also understood the commitment and local ties the office has to the Washington community.

“I used to say to people if you just want to be a prosecutor in federal court, probably best to apply to the Eastern District of Virginia or the Maryland office,” says Taylor. “But if you want to be a trial lawyer and work on fascinating cases—sometimes heartbreaking, admittedly, but the cases that affect the day-to-day lives of your community—you want to be here trying cases in Superior Court.”

It’s November 24, 2009, and Thomas Bednar has one of those heartbreakers. The University of Virginia law-school grad was one of the first of the new AUSA class to join the office, in April, but he still managed to land his last choice in assignments: handling sex-offense and domestic-violence misdemeanors.

These cases—such as his first trial, about an incident where two female roommates had beaten each other up—were unlike anything he’d ever dealt with at his former job as an associate at Jones Day.

By mid-autumn, he was given a new, even tougher portfolio, known around the office as “the kid caseload.” Some of these matters still come out of the sex-offense-and-domestic-violence misdemeanor section, but some are also categorized as general misdemeanors. The common factor among them is that they all involve children, either as victims or witnesses to crimes.

Bednar, 31, comes off as a bit stoic. He doesn’t smile often. He wears conservative suits and preppy ties. It’s tough to imagine him working with children. But as he questions a fifth-grader in the witness box, it becomes clear he’s developed a knack for this.

He’s learned by November that before a trial it helps to sit down with the kids and talk to them about what to expect in the courtroom. Some have seen court shows on TV—Judge Mathis seems particularly popular—so he and the kids talk through the ways real court is similar to and different from television. It helps the kids open up. Sometimes it makes them laugh.

Children were a long way from his long-term goal—to handle national-security cases for the US Attorney’s Office—but all AUSAs have to start somewhere, and the cases were turning out to be more rewarding than he’d first thought.

The “kids cases” are more sophisticated than his first assignment. They involve more police work, more thorough investigations, and more paperwork. As a result, the office allows him more time to work; his total caseload has been reduced from about 100 cases to 60.

Today the fift

h-grade girl on the stand has been through a lot. She and her sister say they were touched sexually by a stranger who snuck into their bedroom after they’d gone to sleep. The man they say is responsible is now seated in the courtroom in handcuffs and an orange prison jumpsuit.

Bednar uses simple phrasing that’s easily understood by the girls. He needs them to describe the man as specifically as they can, even though the bedroom was dark. “Could you tell if he was thin, fat, in between?” Bednar asks.

He moves on to more uncomfortable questions. He asks the fifth-grader to explain how she was touched. She makes a rubbing motion over her chest and says the man also touched her “private parts.” She’s barely audible.

During Bednar’s closing argument, the judge interrupts him. He pushes Bednar on the fact that the girls’ bedroom was dark and neither of them clearly saw the man’s face. They were able to identify the suspect only by the clothing he was wearing, including a distinctive-looking jacket covered in patches.

Bednar can’t dispute this, so he tries to turn it into a positive. He tells the judge that the girls testified candidly about what they could and could not see, which shows they’re credible witnesses who aren’t trying to embellish the facts.

In his closing argument, the defense attorney hammers on the issue of the dark room. Ultimately, the judge says that he believes the girls’ story and that he has very little doubt the defendant is guilty. But even the small amount of uncertainty is enough to require a not-guilty verdict.

Bednar will spend much of the upcoming Thanksgiving break thinking about what he could have done differently to win the case. But with dozens of cases to worry about, he says, “you can’t be perfect and you can’t beat yourself up because you weren’t perfect today.”

He learned about handling a heavy workload under a deadline on the student newspaper at UVa., where he was an undergrad before law school. The Charlottesville campus was cosmopolitan in a way that his hometown of Cedar Rapids, Iowa, never had been—diverse, affluent, intellectually stimulating—and encouraged his interest in history, which led to an interest in the law. As a kid, he had read about famous statesmen and Presidents and realized they had all been lawyers.

Washington was the obvious next stop after he finished law school in 2004, though he had no idea how to get into government. He decided to go to Jones Day—one of the nation’s top firms—to get some experience while he figured out more specifically what he wanted to do. He ended up spending four years as a litigation associate, a job in which his typical clients were large corporations.

Halfway into his stint at the firm, Bednar spent a year clerking for Judge Royce Lamberth—now chief judge—on the US District Court for the District of Columbia. Watching the AUSAs pass through Lamberth’s courtroom, trying weighty federal cases, piqued his interest, and he soon decided that the experience he could gain as an AUSA would be well worth the $100,000-plus pay cut he’d have to take.

Six months in, it seems the right decision. While many cases are dismissed before they make it to trial, or defendants accept plea offers, Bednar has argued 30 trials since he started in the office.

“Those are trials I did,” he explains. “It’s not like I second-chaired them or had any help.” It’s the kind of experience he never could have gotten at his law firm, because large pieces of corporate litigation can take years to get to trial, and they often settle before then. “You have people that are very experienced partners, and they haven’t been involved in double-digit trials.”

While Bednar—who has been in the office the longest of the three—has moved on to a more sophisticated caseload in the autumn of 2009, AUSA Kathleen Connolly, who didn’t arrive until late July, is still getting what prosecutors call a “baptism by fire.” She’s a misdemeanor “calendar assistant,” meaning she’s assigned to a different misdemeanor courtroom each day, where she handles whatever happens to be on the calendar. Mostly the matters are status hearings—in which a defendant checks in with the judge to set a trial date or determine the next phase in a case. In those instances, the line assistants take part in setting the case’s schedule. But the judges also have several trials each day, and the line assistants handle those as well.

It’s unlikely that the misdemeanor calendar assistants will have previously seen any of the cases they have to argue. While they each have their own portfolio of cases they’re responsible for preparing for trial, there is no guarantee these will actually be the matters they end up trying. The volume of misdemeanors in DC Superior Court makes this impossible.

Calendar assistants may have only a few minutes to review the casework before a trial begins, so it’s essential that their colleagues have prepared the cases in a well-organized way.

The misdemeanor assistants go through two to three weeks of training before they start trying cases. But nothing compares to standing up in court and arguing for the first time.

Connolly’s first day in court after completing her two weeks of training was August 3—and she ended up with a drug-possession trial that day. “Nerve-racking” is how she recalls that first experience.

While the first months of an AUSA’s career can be brutal, the assistants are expected to make at least a four-year commitment, during which time they rotate through assignments in Superior Court, the DC and federal appeals courts, and federal district court. They can leave before the end of that time, but doing so is frowned upon. As hard as the constant churn of the calendar was, Connolly didn’t have any intention of leaving early—this is what she’d long wanted to do.

The public-service ethic surrounded Connolly, 33, when she was growing up, with a public-schoolteacher mother and a father who worked in local government. After college at Drew University in New Jersey, Connolly joined the Peace Corps—as had her dad and sister before her. She moved to Benin, in West Africa, where she taught English and worked on women’s education issues and AIDS prevention for two years.

She viewed the law as a way to continue to help people, but on a scale that exceeded the one-on-one, grassroots nature of the work she had done with the Peace Corps. She attended Catholic University’s Columbus School of Law. While a student, she tried a case in DC Superior Court as part of a legal clinic that allowed students supervised by professors to represent indigent clients. When it was over, the judge encouraged her to become a trial lawyer.

The following summer, she interned at the US Attorney’s Office for the Eastern District of Virginia, and the experience left a strong impression. “It seemed like the people there really cared about the work they were doing,” Connolly says.

After graduating in 2006, she spent two years clerking with the Staff Attorney’s Office for the Second Circuit Court of Appeals in New York City. She stayed at the court for a third year to work on immigration cases before applying to join the US Attorney’s Office.

When Connolly started, the prosecutor overseeing the rotation of line assistants was Ben Friedman, then special counsel to the US Attorney.

In his fifth-floor office, Friedman gestures to a big magnetic whiteboard on his wall, with hundreds of color-coded magnets stuck to it. Each one contains the name of an AUSA, organized by division and section.

Friedman explains that a new line assistant starts in one of two sections: in misdemeanors—as Thomas, Bednar, and Connolly did—or appellate. The appellate section, where assistants work on writing briefs and presenting oral arguments in the DC Court of Appeals and the US Court of Appeals for the DC Circuit, is much calmer.

The next step up is the felony trial unit, which—much like general misdemeanors—mostly involves gun- and drug-related offenses, but on a more serious scale.

From there, assistants rotate into the felony major-crimes section, which includes the most serious felonies—such as burglaries and car thefts—committed in the District, other than homicides and rapes. Only more senior prosecutors who want to work on homicides or rapes are assigned to them. Such cases are never a required part of a lawyer’s time in the office.

Assistants spend the final part of the rotation handling cases throughout the sections of the federal-court division, which includes national-security, fraud-and-public-corruption, narcotics, and organized-crime cases. After that, they either leave or apply for more permanent assignments within the office.

Though the new line assistants rotate on a somewhat predetermined schedule, individual performance and recommendations from their supervisors are considered. Ultimately, with the U

S Attorney’s approval, it’s up to Friedman to weigh all these factors to decide when each assistant is ready to progress and where he or she will go.

He admits that the giant whiteboard is more for show than for practical purposes, because he also keeps track of everyone’s assignments in a computer database. But the line assistants like to stop by to check out whether their colleagues’ magnets have advanced on the board.

Says Friedman: “You don’t get into this office unless you’re a competitive person.”

WINTER: THIS IS THE BIG TIME

By early 2010, Connolly and Bednar have moved up to felonies, meaning that for the first time they’re facing juries in their trials. Making a convincing case to a panel of 12 people with varying perspectives requires a whole new skill set.

“Judges have seen it all,” Connolly says. “You don’t need to explain as much when you’re doing a bench trial as you do with a jury trial.”

In felonies, the assistants no longer have the unpredictability of showing up in court and handling whatever comes up that day. Instead, they’re each assigned to a specific judge. They’re given the judge’s schedule of trials and other matters months in advance, so they have time to prepare. They handle the cases from the arraignment all the way through sentencing, unlike in misdemeanors, where they were trying cases they’d reviewed only minutes earlier.

Though Connolly is relieved that her trials are now cases she has prepared herself, felonies require much more research. Since advancing to the new caseload, Connolly has had to meet with witnesses nearly every day. In the drug- and gun-related cases she’s been assigned, most of her witnesses are police officers. She talks with them about the crime scenes and asks for any photos and notes they took. She strategizes about how many witnesses to call and in what order she should put them on the stand.

Despite weeks of preparation, Connolly is still visibly anxious on the day of trial. It will be only her second time in front of a jury. In the minutes leading up to opening statements, she’s rushing around the courtroom, her shoulder-length blond hair slightly disheveled. She needs to find a working outlet for her laptop. She’s hauling poster-size photos up to the counsel’s table. In between gulps of water, she flips through a thick binder stuffed with documents and introduces herself to the court reporter.

Aside from her cases, something else has been weighing on Connolly. She has realized she doesn’t feel happy, though she’s not quite ready to accept the reason. She didn’t enjoy being in court when she was handling misdemeanors, but she chalked that up to the chaos. Since moving up to felonies, though, she hasn’t felt any better.

She reminds herself that this is the job she’s wanted since law school. She has worked hard to get here, and she’s not willing to give up on it. She’s still new to felonies. There’s a chance things will improve once she’s more settled.

When the jury filters in and Connolly walks into the well of the courtroom to face them, she’s smiling and seemingly calm.

“This case is about a man who was doing his job,” Connolly begins. “That job was to sell cocaine on the streets of DC.”

The defendant is accused of distributing crack cocaine to undercover police officers on five occasions. The jury will have to listen to Connolly describe all five charges, and she can only hope she chose people who will be patient and interested enough to pay attention to the details.

As is typical, Connolly had just a week of training in the felony section after she was promoted from misdemeanors. Then she had to get back into court. Jury selection was a focus of that training week, and she has the mechanics of it down—where to stand during the selection process, how many people you’re allowed to strike, and myriad other details.

The more subjective parts are mastered with time. When she chooses jurors, Connolly pays attention to whether they look her in the eye or stare at the floor, where in the District they live, and what they do for a living. Engineers, she says, have a tendency to overthink a case. More experience will help her further zero in on characteristics to look for—but there’s always a certain amount of luck involved.

This jury appears engaged as Connolly lays out her case. She walks them through the way an undercover “buy” works. One undercover officer buys the drugs, while another officer, acting as “the eyes,” watches the sale unfold.

Connolly is soft-spoken but animated as she describes how each transaction between the defendant and the officer occurred. She knows the case well enough to speak from memory.

The sales happened over several months, which raises a question: Why wasn’t the defendant arrested after the first sale? Connolly explains that the five “buys” were part of a continuous investigation.

The defense presents a different version of events. In his opening, the defense lawyer says that the five alleged drug deals were actually a series of failed “buy-bust operations.” A buy-bust is police lingo for buying drugs from a dealer before arresting him or her. The defense attorney contends that the police failed to complete their buy-busts, which is why the defendant wasn’t arrested until the fifth try. It was only to avoid embarrassment, the lawyer tells the jurors, that the police used the excuse that they were targeting the defendant as part of an ongoing operation to explain why they didn’t immediately arrest him.

While lawyers can try a misdemeanor within an hour or two and get a nearly immediate verdict from the judge, a jury trial such as this one can go on for days. There’s more explanation involved to make sure jurors understand terminology such as “buy-bust,” and there’s a lot more evidence to introduce.

There’s also the fact that almost nothing ever starts on time in Superior Court. Jurors show up 20 minutes late. New evidence may turn up minutes before the start time of a trial, which means the lawyers need extra time to review it.

Closing arguments in the drug case start by 4 pm on the second day of the trial. Just as Connolly begins to speak, a field trip of about two dozen foreign judges who have been observing gets up, loudly shuffles around, and leaves. Connolly is unfazed. She reviews each drug transaction a final time, demonstrating for the jury how she says the defendant retrieved the bags of crack from within his shirtsleeves.

The jurors deliberate until 3:30 the following afternoon. They find the defendant guilty on three of the five counts.

On a weekday morning, the security lines at the DC Superior Court’s Moultrie Courthouse can wind out the front doors all the way to the parking area. A mix of jurors, witnesses, defendants and their family members, and some lawyers await their turns through the metal detectors.

The crowds are mostly African-American—one morning, 3 of the 40 people in line were white. As a testament to the racial and socioeconomic divisions that still run through DC, the majority of violent crimes take place in predominantly African-American neighborhoods, and according to DC’s Pretrial Services Agency, about 87 percent of people arrested in DC are black.

Though a few people in line may be in suits, most are in jeans, T-shirts, and other casual clothes. Sometimes ambulances are out front for witnesses or defendants who are drug addicts and have passed out from dehydration or other medical emergencies while in court. Because this is where the District’s street crimes are prosecuted, Moultrie is a gritty place.

This scene outside the courthouse offers a glimpse into one of the biggest challenges faced by the prosecutors who try cases in the District. They have to overcome their cultural and socioeconomic differences from many of the witnesses and jurors they count on to make their cases. Often, these individuals come from parts of the city, such as neighborhoods east of the Anacostia River, where trust in law enforcement and the judicial process has been eroded by years of crime.

The AUSAs’ new boss, Ronald Machen, has made confronting those divides a top priority since arriving in February 2010. The line assistants have noticed the change since Machen took over. They receive regular e-mails requesting—though not mandating—that they attend neighborhood meetings and other activities.

“Residents need to feel connected to their prosecutors,” Machen explains. “You need to be there in times before tragedy strikes, so when tragedy does strike, they know who you are, they trust you, they’re willing to be witnesses, they’ll go into court and serve as jurors.”

One attendee at a Southeast DC event hosted by the US Attorney’s Office says law enforcement didn’t take her son’s shooting seriously enough. “They never caught the guy,” says Mona Toatley, who lives in a housing project in the Barry Farm neighborhood. “They say, ‘That’s just another black guy who got shot.’ ”

Her remarks highlight another problem prosecutors face: No witnesses to the shooting are willing to come forward. “People in this area are afraid to report anything because they’re afraid of retaliation,” Toatley explains.

Michelle Thomas knows that reluctance all too well. She first noticed the divide between residents and the justice system while she was growing up.

Although she hails from a middle-class, college-educated family—her mother was a hospital administrator, her father a postal worker—she grew up, in her words, in “the ’hood” in Oakland while the crack-cocaine epidemic was at its peak. Thomas watched as her friends became pushers. She saw some of them get thrown in jail for years while bigtime dealers went untouched.

That environment, Thomas recalls, created “a culture of ‘you don’t trust the police, you don’t rat on people, and you just handle things yourselves.’ ” That sense still permeates her interactions with the witnesses in her cases.

The line assistants understand the importance of community outreach, but it can be hard to make time for the events in their overpacked schedules.

Thomas is also now dealing with another set of challenges. After feeling lethargic and experiencing muscle pain, she went to the doctor in January.

By April—when she’s trying the domestic-violence case against Lisa’s boyfriend—the doctors are still running tests. They can’t figure out what’s wrong with her. Thomas doesn’t want to tell her family—the doctors don’t even have a diagnosis, so there’s no use worrying her loved ones unnecessarily.

And Thomas’s work is keeping her plenty distracted. It’s a busy week—by Thursday, when she gets to Lisa’s case, she has had three other trials.

When she accepted the job, she knew it would take a toll. At night, she no longer tunes in to the dramas—such as Law & Order—that she used to love. Instead, she watches episodes of her favorite Disney Channel cartoon, Phineas and Ferb, and looks at photos of her nieces to clear her thoughts before she goes to sleep.

Thomas doesn’t want or expect any sympathy. She knows that all of her colleagues balance a demanding workload with other stresses. “Everyone who works here has issues,” she says. “We have lives.”

SPRING: SPECIAL DIETS AND RELIGION

Thomas Bednar is a long way from his youth in Cedar Rapids. He laughs recalling the time when two teenage girls who were witnesses in a case had to explain to him what the phrase “Kirking out” meant. It’s a reference to Star Trek’s Captain Kirk that means being spaced out on drugs.

Before he became a line assistant, much of Bednar’s knowledge of the drug trade came from the HBO series The Wire. Now he talks with ease about the way a typical drug deal goes down.

On March 16, he’s trying his fourth jury trial, against a man charged with selling crack cocaine to an undercover officer. He won guilty verdicts in the first three.

The hitch in this case is that the defendant wasn’t the one who actually gave the drugs to the officer. Another man, whom Bednar argues the defendant was using as a go-between, made the transaction.

Bednar’s first witness, the undercover police officer who bought the drugs, testified that this is a typical maneuver used by drug dealers to avoid getting caught. As payback for helping, the officer said, the go-between will usually get money or drugs.

Now the alleged go-between—we’ll call him Leon—is on the stand. He’s the defense’s only witness. During direct examination, it becomes apparent that Leon has a mental disability. His responses are rambling and often mumbled and hard to understand.

One thing is clear from the defense lawyer’s line of questioning: Leon is claiming he sold the drugs in order to pay for a prostitute. He says the defendant had nothing to do with it.

When it’s Bednar’s turn to question Leon, it’s a moment that displays the stark contrast between Bednar’s own background and the experiences of many of the civilians who come through DC Superior Court.

Because he realizes Leon is prone to veering off topic, Bednar has written down a few objectives he hopes to accomplish during the cross-examination to help them both stay focused.

Bednar is self-conscious that he’s a thirtysomething white lawyer questioning an African-American drug addict in his fifties. Though he needs to be firm with Leon, he doesn’t want to come off to the jurors as disrespectful or demeaning to this man who is much older than he is and obviously from difficult circumstances. Bednar has experience working with witnesses with mental disabilities from his time on misdemeanor domestic-violence cases, so he can at least rely on that.

He succeeds in getting some clear answers out of Leon, who directly contradicts the testimony of the officers who made the drug bust. For instance, Leon says he handed the drugs through the window of the undercover officer’s van, while the officer said he got out of the car to buy the drugs. Bednar could possibly use these contradictions to attack Leon’s credibility as a witness.

But the questioning doesn’t totally go Bednar’s way. He asks Leon if drug dealers sell to people they consider snitches—the implication being that Leon is lying for the defendant to keep his drug supply from drying up. The defense attorney objects to the question, and the judge sides with him.

Closing arguments wrap up by 3 pm, and the jurors leave to begin deliberations. By 4:45, they still haven’t reached a verdict, so they’ll have to try again in the morning.

During the short walk back to the US Attorney’s Office, Bednar ticks off the list of concerns that are already on his mind. He’s worried he was too flippant with Leon. There’s also a juror who appeared to him to be losing patience.

But he doesn’t have much time to dwell on the day’s trial—even though it’s past 5, he still has a staff meeting to attend and more cases to prep.

The following afternoon, he’ll learn that the jury was hung, unable to reach a verdict. Some jurors wanted more physical evidence, such as fingerprints taken from the Ziploc bags of drugs.

The line assistants often complain that jurors unrealistically want the kind of evidence they see on TV shows such as CSI.

Next time, Bednar will consider putting on an expert witness who can testify that it is nearly impossible to get fingerprints off of a plastic bag.

Thomas is elevated to felony cases by the end of April, about the time the doctors first utter the word “cancer.” At one point, they tell Thomas she may have leukemia. But they aren’t sure.

They’ve determined that Thomas’s body isn’t processing enough nutrients from her food. They’ve been putting her on special diets to see if her body will respond positively.

The only people Thomas has told about her health problems are her supervisors and three fellow AUSAs. She’s grateful for how supportive they’ve been. When the doctors took Thomas off of solid foods for one of the diets, her supervisors offered to stock her office with liquids.

But the work doesn’t stop, and Thomas is still putting in the same 12-to-15-hour days she was when she was handling misdemeanors.

Still, she doesn’t regret her decision to join the office, though she admits the stress is probably a factor in her health. “I am a woman of faith,” says Thomas. “I know that God has a purpose for my life.”

For now, being an assistant US Attorney is a part of that purpose.

Bednar received an e-mail in February about a chance to spend a year working for the Department of Justice on Guantánamo Bay detainee cases. The chance to do a temporary “detail” at Justice is another benefit of working in the US Attorney’s Office. This assignment would involve handling habeas corpus cases where the government is arguing for the continued right to hold detainees. After a year, Bednar would return to the US Attorney’s Office and continue his four-year rotation.

To Bednar, it sounded like an ideal chance to get more experience working in national security—the area of the law where he ultimately hopes to focus his career. At Jones Day, he did some work that involved studying the rise of Islamic terrorist groups and the funding of terrorism. When he clerked for Judge Lamberth, he assisted with a number of national-security cases, including one that eventually made it to the Supreme Court.

Bednar applied for the detail, highlighting these past experiences, and in March he found out he’d been accepted. But by early June, he’s still working away as a line assistant because the security clearance is taking longer than expected.

In anticipation of Bednar’s leaving for a year, the supervisors in the US Attorney’s Office have assigned another assistant to take over his caseload—and his office. Bednar is now in a sort of limbo. He’s working out of a break room and pitching in to help colleagues where he can as he waits to get cleared.

SUMMER: EVERYONE IS CONNECTED

The pace slows down for Kathleen Connolly over the summer as well. One Friday, she’s reveling in the fact that she finally had time to clean off her desk: “I keep looking at it. I’m like, ‘Look at how nice my desk looks!’ ” Her judge is out of town for a conference, which means she hasn’t been in court for almost a week—as much of a break as any AUSA could hope for. Now that she’s been in felonies for several months, she has a better handle on the work. Her caseload has been reduced, which means her typical work week is down to 60 hours; she was previously putting in closer to 80. Today Connolly is leaving by 5:30 to go to happy hour with some colleagues.

For the first time since joining the office, she has some semblance of a work/life balance. The trouble is she’s still not happy. Before, she wondered if it was just the stress and crazy hours that were keeping her from loving the job. Now she’s sure there’s more to it than that.

What Connolly does enjoy about the office is the camaraderie. “We bounce ideas off each other every single day,” she says. “To do this job without good people—I can’t imagine it.”

That’s also what nearly every alumnus of the office mentions first when asked about the experience there. All say the strong friendships built there are a natural consequence of the intense pace and pressure. It’s just not possible to handle the workload alone.

“You can’t survive unless you help each other out,” says Kenneth Wainstein, who was an assistant prosecutor in the office and also the US Attorney for DC from 2004 to 2006. “One person’s head starts to go under, the other person who might have a little bit of breathing space will reach over and help them out.”

Those bonds last beyond the office, a fact that can be helpful for the many prosecutors who go on to become prominent members of the city’s criminal-defense bar. Robert Spagnoletti, now a partner at the law firm Schertler & Onorato, spent 13 years as an assistant US Attorney in DC. He points to one of his recent high-profile trials as evidence of the enduring camaraderie.

He was on the defense team in the obstruction-of-justice case against three men accused of covering up evidence in the 2006 murder of Washington lawyer Robert Wone in a Dupont Circle rowhouse. “You would expect it to be an extraordinarily tense relationship with the prosecutors,” says Spagnoletti. “Not so. Not at all. Even though we fundamentally disagreed with everything they did.”

Everyone involved in the Wone trial, he explains, was connected through the US Attorney’s Office. The judge in the case, Lynn Leibovitz, is a former assistant prosecutor, and she had started in the office a few months prior to Spagnoletti’s arrival. He took over her cases when she was elevated to new caseloads. David Schertler and Thomas Connolly, two of the other defense attorneys in the case, also overlapped in the US Attorney’s Office with Leibovitz, as well as with Glenn Kirschner, who remains an AUSA and was the lead prosecutor in the Wone trial.

As a result of these connections, some of the negotiations with the prosecution, says Spagnoletti, took place over beers.

THE ONE-YEAR MARK: CHANGED LIVES

Though temperatures are still pushing 90 degrees, fall is approaching. It’s September 7, 2010, and nearly a year after becoming a prosecutor, Michelle Thomas’s jury trial is ready to start. Although she’s been in felonies since April, none of her other cases have made it to verdict. She’s nervous today because it’s been months since she argued a case in court.

The defendant in this trial is charged with several gun-related offenses, including unlawful possession of a firearm and carrying a pistol without a license.

Thomas delivers an energetic opening statement. Telling the jury how the defendant took off running when he was approached by a police officer on a bicycle, she holds her hands out in front of her as if to grip the handlebars. Then she leans in toward the jury, pumping her fists as if running at full tilt. The jurors’ eyes are locked on Thomas. As the defendant ran from the officer, she says, he began discarding property. She makes tossing motions to show how he threw a cell phone and a baseball cap.

Finally, he ran by a woman. Thomas says the woman, who will testify in the case, saw the defendant throw something else. When she went to see what it was, she found a gun lying on the ground. Thomas will attempt to convince the jury that the gun indeed belonged to the defendant and hadn’t been on the ground prior to that police chase.

Despite the courtroom display of energy, Thomas is still tired. The doctors have backed off their earlier theory that she has leukemia, but they haven’t ruled out cancer altogether. Her condition hasn’t improved, and her blood-cell counts are still off.

Thomas has continued to deal with this mostly on her own. “I can’t tell my family because my family would freak out,” she says. “They’re so far away. It just would not be good.”

The trial doesn’t go her way. The jurors find the defendant not guilty because no one actually saw the gun leave his hands. “In the grand scheme of cases like this, we had more evidence than general,” Thomas says. But she’ll have another shot soon enough. She has back-to-back trials scheduled through December.

It has been a tough year. But despite the occasional not-guilty verdicts and her health issues, Thomas remains committed to being an assistant US Attorney: “This job is more than just a job to me. I feel like it’s ministry.”

Thomas Bednar’s security clearance came through in July. He now works in a downtown DC building used by the Justice Department, and though he’s excited about the new opportunity, he misses his old routine at the US Attorney’s Office. “I miss being in court every day,” he says. “I imagine I’ll sneak out sometime when someone’s got a trial going on and spend an hour or two [watching].”

The Guantánamo Bay cases are a lot different than his assignment working on local drug- and gun-related felonies. They’re handled in federal court, and instead of working on dozens of cases, Bednar is assigned to only a few of the habeas matters at a time. Any more than that would make it impossible to conduct the intense research that goes into them. Bednar is responsible for assembling and presenting the government’s evidence in the cases of individual detainees to prove they’re being held lawfully at Guantánamo Bay. The habeas cases often involve piecing together stories that unraveled over the course of a decade, whereas a local crime such as a drug deal typically happens in a matter of minutes.

He’s hopeful that spending a year on this detail could help him land a permanent assignment working on national-security cases in the federal division of the US Attorney’s Office after he completes the initial four-year rotation.

But that’s no longer his only interest. His work in the domestic-violence section turned out to be surprisingly rewarding, and he doesn’t rule out wanting to revisit that type of work in the future.

“Every case has a human story,” he says as he reaches into the pocket of the suit jacket draped over his chair. He retrieves several photos of a house with the front windows completely smashed in. The pictures were evidence in one of his previous misdemeanor cases where an abusive ex-husband had rammed his truck through the front of his ex-wife’s house.

Bednar says the woman had endured years of abuse that Bednar describes as “borderline torture,” but she had been too afraid to follow through with charges against her husband. After their divorce, when the man drove a truck into her house, she didn’t have any choice about notifying the police.

The judge gave the man six months in prison, the maximum sentence. Upon hearing the sentence, Bednar says, the woman broke down in tears. “That was extremely vindicating to see someone who you could just tell was always scared to say anything, and finally it was out of her hands,” he says. “That’s why I was glad I did domestic violence.”

It’s that moment, as Phillips explained to the class of AUSAs a year before, that makes the job—the hours, the courtroom chaos, the comparatively low salary—worthwhile.

Kathleen Connolly has reached a much different conclusion over the past year. On a sunny afternoon in late September, she takes a long pause and sighs before speaking. “If you like prosecuting, this is a great job—it really is,” she says. “You’re getting a variety of cases, and working with good people, smart people.”

But there’s more.

“You have to love being in the courtroom, because you’re doing it so much in this job,” Connolly says.

“And I don’t.”

She had a difficult time accepting that realization over the course of the year. This was supposed to be her dream job. Ever since she tried that first case in Superior Court as a law student, she thought the courtroom was the place for her.

But after a lot of “soul searching,” she finds herself questioning whether she really believes that anymore. After she wraps up her current caseload, Connolly’s next assignment will be to handle cases that are on appeal. Working in the office’s appellate section primarily involves researching and writing briefs. The assignment requires very little time in court.

Connolly is looking forward to the appellate work, though she hasn’t ruled out leaving the office—or the legal profession altogether.

As for what her future holds, says Connolly: “Jury’s out.”