Tim Warner quit a corporate job to minister to people living in poverty. All photographs by Brooks Kraft

The first time Tim Warner went knocking on doors, he had on the navy-blue suit he’d worn to the office that day. It was pouring, so he’d put on a long raincoat and a felt fedora. He was carrying a black umbrella.

He got out of his car in front of the Nob Hill Apartments in Long Branch, a predominantly immigrant neighborhood a few miles from downtown Silver Spring. There, his colleagues were getting ready to pair up and approach people they’d never met. They looked at Warner and laughed.

What were you thinking? Warner said to himself. You look like an immigration official who’s coming to lock them up.

“Sorry,” he said to his coworkers, taking off his tie. “I should have known.”

Warner’s job was to reach people in Montgomery County who weren’t being reached, low-income residents who might need help and not know how to get it. As a minister, he’d tried to clean up street corners in Baltimore and asked people panhandling in DC to have lunch with him. It’s relationships that transform people, he likes to say.

That night, Warner met a man from Honduras who worked 16 hours a day driving an airport limousine. He talked with young people from Togo and Ghana who were enrolled at Montgomery College and had money for books but not food.

People in Montgomery County probably know more about poverty in Africa than they do about the need right here, he thought later.

Since then, he’s knocked on more than 1,000 doors in one of the nation’s richest counties. He’s found families at home in the dark, living rooms without furniture, two-bedroom apartments sleeping 12. He’s heard of mothers saving money by filling baby bottles with mostly water and met kids for whom a snow day means a day without lunch.

This, he says, is the other Montgomery County.

Poverty in a wealthy suburb doesn’t look like it does in the inner city—you won’t see gutted buildings and boarded-up windows. But it’s there, a few miles from the Saks Fifth Avenue in Chevy Chase, not far from the million-dollar condos in downtown Bethesda, sharing a classroom with middle-schoolers in $100 Ugg boots.

At a January tribute to Martin Luther King Jr. at Strathmore music center in North Bethesda, county executive Isiah Leggett spoke of an increasing gap between the rich and the poor. “Hidden among this general affluence are people who are hurting,” he said. “There are more students in Montgomery County Public Schools eligible for free and reduced-price meals than there are students in the entire DC public-school system.”

Nearly a third of the county’s 144,000 public-school students receive meal benefits. To qualify, a family of four must have a yearly income of less than $41,000. At Broad Acres Elementary in Silver Spring, more than 90 percent of students fall into that category.

About 7 percent of the nearly one million people who live in Montgomery County fall below the federal poverty guidelines: about $18,500 for a single parent and two children, $26,000 for two adults with three children.

Many residents earn too much to qualify for help from the federal government but not enough to pay their bills. Over the past three years, the county’s Department of Health and Human Services has seen a 60-percent increase in applications for food stamps and other forms of assistance—available to legal residents only—but it has also seen a steady increase in the number of denials.

Warner knows firefighters, police officers, nurses, and teachers who can’t afford to live where they work. Montgomery County, which has a median household income of nearly $94,000, has one of the highest costs of living in the country: A single mother with two children has to earn $68,000 a year to meet her basic needs.

“If you sit back and think about it, you have to say, ‘Who are these folks working in the pizza parlor? Who are the people driving taxis?’ ” says Ruth O’Sullivan, who runs a public-housing program in Rockville. She recently opened the waiting list for three- and four-bedroom units and received 2,000 applications in three days.

Warner, who works with faith communities in the county executive’s Office of Community Partnerships, says the challenge in a county of extremes is getting the people who aren’t in need to notice those who are.

Next: "If I had to be poor someplace in America, this would be it."

The Middlebrook Mobile Home Park near Rockville Pike.

There are cracks in the glass door of Pedro and Laura’s apartment building in Gaithersburg. The cinder-block walls and linoleum floor in the hallway look like those in a school cafeteria. The rent for their two-bedroom apartment is $1,200 a month. Others pay less: Neighbors tell Laura the landlord charges $300 more if you’re undocumented, which she and Pedro are. It may be unfair, but it’s not illegal.

On the wall above the dining table are streamers left over from daughter Isis’s third-birthday celebration. Laura and her older daughter, Ingrid, went to a dollar store and found birthday decorations and animal stickers. Ingrid was giggly all day. Pedro, who prepares meat and vegetables at a deli, brought home a cake with fruit on it, and the family took pictures of Isis blowing out her candles.

Warner met the Salvadoran couple in the fall of 2009 after a colleague from the Neighbors Campaign—a joint project between county government and nonprofits including Family Services, Catholic Charities, and Impact Silver Spring—knocked on their door. He was struck by the way they looked at each other. Laura described her husband as an honorable man who valued family over everything else.

I can only hope my wife says those things about me, Warner thought.

The Neighbors Campaign—now the Neighborhood Opportunity Network—was formed two years ago after county leaders realized that lots of the people in need weren’t getting help. Some didn’t know how to apply for temporary cash assistance; others didn’t know they could see a doctor even if they didn’t have health insurance.

“If I had to be poor someplace in America, this would be it,” Warner says. “The resources are there—finding them is another thing.”

Aside from pointing low-income residents to services they might not know about, the network tries to bring strangers together to see how they can help one another. Maybe there’s a woman on the third floor who runs a low-cost daycare service and a mother upstairs who needs it. Maybe there’s a guy who’s great at installing cabinets but can’t find work and someone living next door who needs a reliable carpenter. If they never meet, Warner says, they’ll never know.

For Laura and Pedro, the knock on the door was a welcome one. They’d come to America three years earlier from a place where they passed bodies in the street. The government didn’t give out food stamps, they say—people died of hunger. The civil war was over, but the violence had escalated. Laura knew of a woman whose daughter had been snatched from her arms and murdered by gangsters who wanted money.

Before they left El Salvador, she and Pedro asked God for one thing: to take them somewhere they could live a calm life.

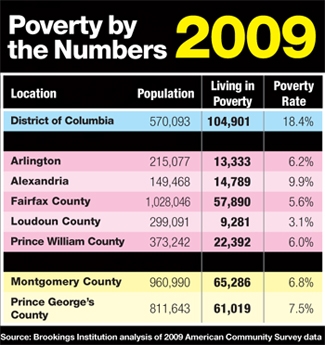

A recent Brookings study found that the number of poor people living in suburbs increased by 37 percent between 2000 and 2009.

“These trends were in place even before the great recession,” says Elizabeth Kneebone, a researcher at Brookings’s Metropolitan Policy Program.

Montgomery County saw its poor population during that time increase from 47,024 to 65,286. The number of people living in poverty in Fairfax County rose from 43,396 to 57,890; in Loudoun County, the number doubled from 4,637 to 9,281.

One reason is that more immigrants are arriving in this country poor and staying that way. When Laura applied for Medicaid benefits for Isis, who was born in the United States, the woman helping her asked to see more paperwork because she couldn’t believe a family of five was surviving on so little money. About 30 percent of the population in Montgomery County is foreign-born, including an estimated 35,000 from El Salvador. Maryland has the fourth-largest population of Salvadorans in the United States.

“The immigrant community in this region really started in the heart of DC—Adams Morgan, Columbia Heights,” says BB Otero, president of CentroNia, a DC-based educational organization that’s expanded its services to Montgomery County. Once those families got settled—saved money, found jobs, learned the language—they moved to the suburbs in search of more affordable housing and better schools. Friends and relatives followed. “The next wave came directly to the suburbs. They didn’t have to pass through the central city.”

When Tim Warner was asked to work on the staff of the county executive three years ago, more than 55,000 people were living below the federal poverty line. Tens of thousands more couldn’t meet the county’s standard for self-sufficiency. The county was facing a $200-million budget shortfall. The nonprofits that were there to help were struggling.

“There just wasn’t enough money to deal with this upswing in requests for emergency services,” Warner says. “So we got together and said, ‘What can we do creatively to deal with this?’ ”

He helped open three neighborhood service centers in parts of the county that needed the most help: Gaithersburg, Wheaton, and the Long Branch area of Silver Spring. Then they paired up—a Spanish speaker and an English speaker, when possible—and started knocking on doors, often involving church groups in the effort.

Warner has had doors slam in his face. He understands why it’s hard for people to believe he’s not selling anything. He realizes that when a woman looks through the peephole and sees a six-foot-six stranger staring back at her, she may not answer. But most people do open the door: Since 2009, Warner, his colleagues from Impact Silver Spring, and volunteers have knocked on 11,800 doors and had conversations with 2,900 people from 78 countries, many of whom might otherwise have never sought help.

“We’re very good at giving clothes away and feeding people when we have extra stuff to give,” he says. “What we’re not good at is asking those people, ‘Why do you need food in the first place?’ ”

Next: The daily life of the immigrant poor.

Warner learned growing up that poor people find a way to survive. He lived in a suburban ghetto outside Philadelphia in a house next to the projects. His mother was an alcoholic who had given birth to him when she was 16; his father wasn’t around. It didn’t surprise him to find out, when he moved here, that there were newborns coming home from Holy Cross Hospital in Silver Spring who slept in a laundry basket. His own bassinet had been a dresser drawer.

By the time he was 12, he’d seen race riots, drug addiction, and domestic abuse. He’d also seen the drunks on the corner raise bus fare for his uncle to get to college every day because they were glad to see someone making it. Tim had carried get-well cards from his great-grandmother Mozelle to neighbors who’d just come back from the hospital. He didn’t understand it then, but the $3 in a sealed envelope was her way of telling them they weren’t alone.

It was his first lesson in community. “Cast your bread on the water,” his great-grandmother would say. She’d raised eight children during the Depression and scrubbed floors her entire life. Give away all that you have.

Warner’s own mother had always worked two or three jobs to make sure he and his brother had plenty to eat and nice clothes to wear. For a long time, she cleaned houses. “I know when to put my purse on my shoulder and leave,” she’d say if an employer spoke down to her. When Warner met Laura and Pedro’s family, he thought about her.

Pedro’s job at the deli paid $9 an hour, so the couple’s teenage son, Willian, waited tables to help with rent. Laura took three buses to get to a temporary job at a daycare center. Hard work was all they knew.

Many of the people waiting at Manna Food Center in Gaithersburg haven’t always been poor. Executive director Kim Damion hears this line all the time: “A couple years ago, I was a donor—I cannot believe I’m in line.”

She’s had clients with master’s degrees who lost six-figure incomes and had to settle for a $45,000 salary, including some who drove there in luxury cars. A laid-off college professor came to pick up food.

People start lining up at Manna’s warehouse at noon on weekdays. Some residents catch a Metrobus that stops a few blocks away on Shady Grove Road; others pile into a minivan and share the cost of gas. Nobody asks for documentation: If you live in Montgomery County, show an ID, and have a referral from a government or social-service agency, you can come in every 30 days.

"A couple of years ago I was a donor—I cannot believe I am in line."

Manna has seven other pickup locations that are open once a week. A white box truck loaded with food sits outside St. Camillus Church in Silver Spring on Monday; on Thursday, it’s in the parking lot of the Family Services Center in Gaithersburg.

Manna feeds 3,300 families a month—its numbers nearly doubled between 2007 and 2009. These days, Damion can’t keep enough baby food and diapers on the shelves.

Families receive two boxes of food: One contains 21 nonperishables such as pasta, rice, soup, peanut butter, and canned tuna. The second is filled with produce, meat, milk, cheese, and dessert. Manna partners with local farmers markets and orchards to collect fresh fruits and vegetables. Damion’s clients would rather have an apple with bruises, she says, than no apple at all. The organization hosts food drives at schools and office buildings. People pull up to the warehouse to donate car trunkfuls of food.

Manna drivers stop by 40 supermarkets every morning—including several Giant, Safeway, and Whole Foods stores—and fill the trucks with donations: loaves of bread, rotisserie chickens that didn’t sell the night before, yogurt nearing its sell-by date.

Warner has had doors shut in his face. But through his door-knocking campaign, he and his colleagues have reached 2,900 people, steering many of them to services they didn't know about.

Pedro rarely picks up groceries from food banks because he doesn’t want his kids eating canned foods. Too many preservatives, he says. In El Salvador, he went to college and got his degree in agropecuária, the study of agriculture and livestock. A snack for Isis is red-bean soup or fresh pineapple, not animal crackers.

Fruits and vegetables usually are a luxury when you’re poor, but his family eats them almost every day. “That doesn’t mean we don’t eat meat,” Pedro says through a translator. “We just don’t make certain things.”

He and his wife shop for the best prices: H Mart often has apples for ten cents less than Megamart; Sam’s Club has the cheapest plantains. For clothes, they check Walmart and Ross.

Pedro and Laura weren’t planning to come to America. They owned a house in El Salvador that had a concrete ceiling, a water tank, and a balcony where they could see the mountains and watch parrots fly by. Pedro had a job selling veterinary products. But Laura’s older sister, who lived in the United States, came home for a visit once and had only good things to say.

“What is life like there?” Laura asked.

“Perfect,” her sister said. “It’s very nice, and the kids have huge opportunities.”

Their son, Willian, left for America first. He was 12. His cousins were living in Los Angeles, and Laura’s sister offered to care for him. A few months later, he got into trouble with police for stealing from a mall. Pedro got on a plane to California and discovered that Laura’s sister had yelled at Willian and made him do chores the other kids didn’t have to do. Willian didn’t want to go back to El Salvador, and his parents wanted him to get a good education, so they moved him in with a family friend and tried to call him every other day.

“How are you?” they’d ask.

“Good,” he’d say.

On visits, Pedro saw something different. His son was lonely and cried a lot—he’d never done that at home. Soon Willian told his father he’d sought refuge in a gang. Pedro arrived in LA two days before one of Willian’s friends was murdered.

“The next time we come, it’s going to be to stay,” Pedro said. He wanted to see his son succeed. But it was hard to make it in El Salvador—he knew lawyers and doctors earning less than $1,000 a month. Gangs were rampant. He told Willian, “I’m not going to leave you again.”

Sometimes Tim Warner wonders how he made it out of his little town of Crestmont, Pennsylvania. He can count on one hand the close friends from his hometown who aren’t dead, incarcerated, or addicted to drugs. At its root, Warner says, poverty is powerlessness.

Warner’s family’s circumstances motivated him to go to college, but the people around him made that education possible: the elderly woman at church who got him so excited about reading that he couldn’t wait to deliver the scripture aloud in Sunday school, the chairman of the deacon board who he believes was called by God to shepherd him.

Warner’s stepfather started a janitorial business when Tim was in high school, and he got his first contract at Temple Zion, a synagogue nearby. Warner spent Friday nights finishing up basketball games and then going to set up for weddings. His parents dropped him off at American University in 1979 with a check from Temple Zion to the bursar. That money, along with scholarships and grants, was his down payment on tuition, room, and board.

His plan was to be a doctor—he was fascinated by the heart—but he got off track after one of his professors obtained a paid internship for him at a microbiology lab at NIH. Warner liked breaking cells open and studying DNA, and he found himself pursuing a career in molecular genetics. Before he graduated from college, he had a job as a bacterial geneticist for a pharmaceutical company, working on a vaccine for malaria. He was making more money than he needed.

At 25, he was sitting in first class on a flight to Europe, wondering if the doctors he was going to meet had any idea he had grown up next to the projects. He was traveling in circles very different from the one he’d been born into.

God had to have wanted more from me, he thought.

When Warner’s great-grandmother died, he was a midlevel corporate guy with a wife, two children, a big house, and two cars. He was frustrated because he couldn’t clear his schedule to be with his family right away.

Soon after, he got his calling from God, he says. He didn’t hear a voice, but it was a moment of clarity so profound that it scared him. He was sitting in the front row at Mount Calvary Baptist Church in Rockville when the pastor started talking about Ananias and Sapphira, churchgoers who’d held back their possessions instead of sharing them for the common good.

Warner felt as if the message was for him. He quit his job in pharmaceutical research, went to seminary and was ordained, and took a job on the staff of a United Methodist bishop. A cloud is hanging over Baltimore, the bishop said, and you need to fix it.

Warner pitched tents and set up “saving stations,” where people could come for Bible study, clothing, and free medical checkups. He helped turn an abandoned, rundown church parsonage into a short-term transitional house for heroin addicts. “I lost track of the number of people we were sending to rehab,” he says. “We would pay for transportation to get them out of town.”

He was later appointed to be pastor of a church in Boyds, just north of Germantown, and ministered to inmates at the nearby Montgomery County Correctional Facility, where the warden sometimes sees mothers and sons locked up at the same time. The people he met there were a lot like the ones he’d worked with in Baltimore: Some deserved whatever came to them; others needed another chance. These are real people, Warner thought, not a set of numbers in somebody’s report.

When he asked the warden to send him statistics on where inmates go when they leave, the map he received was nearly an exact match for the one he had of the largest pockets of poverty in the county.

Next: Warner's work with immigrant families and the children of inmates.

From their apartment, Laura and her daughter can see life at the luxury units across the street.

The new luxury apartments across the street from Laura and Pedro’s building rent for up to $2,600 a month. They don’t bother Laura—anywhere you go, she says, you’ll find people who have more than you do—but they bother Warner.

“This monstrosity in front of you used to be one huge low-income apartment complex,” he says, crossing Route 355 in Gaithersburg in his 2001 Toyota Avalon. “These new units can’t be afforded by the people who used to live here. We’ve displaced them and priced them out.”

He’s curious about what happened to those people. They were the working poor, he says, mostly Latinos living from paycheck to paycheck. “Imagine someone who’s lived in these apartments for a dozen years and suddenly somebody’s making the decision that they’re going to tear them all down,” he says. “What do you do?”

It’s families like Laura and Pedro’s that Warner finds himself worrying about the most. The first time they tried to pay income taxes—undocumented immigrants are expected to file and can do so using an alternate identification number—they paid someone $200 to help them; the woman never mailed their paperwork. Pedro pays taxes because of something he read in the Bible: Give to Caesar what is Caesar’s. But it took him two years, on a payment plan, to pay off the money he owed the government after he was scammed.

The couple share a bedroom with their two daughters. Isis sleeps with them; Ingrid has a mattress a few feet away. The sheets and pillowcases don’t match. The wall is bare except for a small framed picture of Tinkerbell.

Pedro recently picked up a second job at a pizza place. He finishes at the deli around 5, goes home to see his kids and change clothes, and leaves about half an hour later. He tries not to work on Sundays, but he won’t say no: “If our family can get a check, I’m not going to let it escape.” Sundays are the day Laura makes a traditional Salvadoran breakfast—eggs, beans, cheese, bread—and they all eat together at the kitchen table. The kids want him to take them to the beach one weekend, but Pedro isn’t sure it’s safe. He’s heard about people getting stopped in Annapolis and asked for their immigration papers. All it would take is one day of bad luck.

Laura is trained to care for infants but can’t find permanent work because she doesn’t have a Social Security number. She has trouble keeping up with her kids’ schoolwork because she doesn’t know enough English.

Still, she says, it’s better than the alternative. Back in El Salvador, she always had to wonder if the police were really criminals. She never felt safe. When she returned home to see a doctor a few months after moving to America, she had a mild heart attack on the plane and had to be rushed by ambulance to the capital city, San Salvador, where she spent seven days. She’d had heart arrhythmias before but had never been properly diagnosed.

“When I was recovering, I had a tragedy happen, something that happens a lot in El Salvador,” Laura says during a conversation at her kitchen table. Pedro asks his older daughter to take the little one into the other room. “It’s something we have a hard time talking about.”

Warner got angry at himself for not knowing what brought Pedro and Laura to America—that they came to save their son—or that the couple went through something so horrific they can’t tell him about it.

He’s known them more than a year and spent a weekend with them at a neighbors’ retreat. He should have made learning Spanish a priority, he says. He should have asked more questions.

“I’ve carried a lot of burdens that didn’t belong to me,” he says. “Why not that one?”

One of the toughest things about his job is knowing when to let something go: “I’ll be praying about Laura and Pedro tonight,” he says. “If God wants me to do something, I’ll know about it.”

When he gets home at night, he tries not to talk about work. He kisses his wife, Paula, an administrator at Stone Ridge School in Bethesda, and eats dinner. He turns on a crime show or a National Geographic Channel show about prisons. Prison work is his passion. Every summer, he runs a one-week camp for children whose parents are incarcerated. On his wall at work, he has a four-by-four-foot picture of Martin Luther King Jr. that was sketched by an inmate at the county jail.

“He did this freehand,” Warner says. The picture, done on six separate pieces of paper, was ready to be thrown out. Warner got hold of it and put it back together.

If he brought his job home, Warner says, he would always be thinking about the boy who came to a youth Bible-study group in Rockville’s Lincoln Park neighborhood a decade ago, got into a fight with another boy, and cursed Warner out. He saw that boy, now an inmate, when he was walking through the jail a few years ago.

“Remember me?” the young man yelled. “From Lincoln Park?” Warner sat in his car and cried, realizing he’d missed one.

Next: David Scull Courts is the only housing project left in Rockville.

Warner’s office is a block from Rockville Town Square, a mixed-use community with luxury apartments, shops, and restaurants. Families stroll along red brick sidewalks; kids run through a fountain in the summer.

A few miles away, tucked behind an industrial park off East Gude Drive, is an old public-housing project called David Scull Courts. Residents are mostly single mothers, some with four or five children. Some are illiterate; others are working toward a GED. Many have fast-food or custodial jobs. They pay 30 percent of their income each month in rent. That may be $50.

On a drive through the neighborhood, Warner isn’t surprised that the reporter and the translator riding with him, both of whom grew up in Montgomery County, never knew this housing project was there.

“We isolate poverty,” he says. “We don’t want to see it.”

He describes many of the people who live here as “chronically poor,” often families who’ve been on public assistance for generations: “There’s a lot of unemployment. A lot of addiction.”

This is the only housing project left in the city of Rockville; a second was demolished in 2004. It’s funded by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development, so residents have to be American citizens or legal immigrants. Undocumented immigrants such as Laura and Pedro don’t have access to programs that use government money.

The group that runs David Scull Courts—Rockville Housing Enterprises (RHE)—has 105 public-housing units. A third of those are single-family homes from the 1950s that look like other houses in the neighborhood.

“You wouldn’t know they’re public housing,” says executive director Ruth O’Sullivan.

RHE also has more than 400 units in its Housing Choice Voucher Program. Formerly known as Section 8, the voucher program offers financial assistance for low-income families to use toward rent anywhere in Rockville. The waiting list has been closed for two years.

At the elementary school near David Scull Courts, teachers struggle to get parents to show up for activities unless the school provides refreshments. One teacher asked students to bring in $2 for a class activity, and a few said their parents didn’t have it.

Because so many schoolkids depend on free meals, Manna Food Center delivers “smart sacks” filled with oatmeal, pasta bowls, tuna, soup, applesauce, and more to about 1,400 elementary students who might otherwise go hungry on weekends. Executive director Kim Damion has dropped off backpacks at her own children’s school in Olney.

On a drive through the neighborhood, Warner isn’t surprised that the reporter and the translator riding with him, both of whom grew up in Montgomery County, never knew this housing project was there.

“You know it’s somewhere,” she says, “but you don’t think it’s in your neighborhood.”

Monica Barberis-Young, a program director for a nonprofit called Interfaith Works, gave a presentation on poverty to a group of lawyers three years ago and noticed a man in the front row who wouldn’t stop fidgeting. As she talked about Tobytown, a small community of low-income residents in Potomac, she saw tears in his eyes. Eventually, he stood up.

“I’ve lived all my life in Montgomery County,” she remembers him saying. “Every morning, I get up in my $700,000 home in Potomac, use my remote to open my car, and drive to my Chevy Chase law office. I get home, and there’s my wonderful wife with my two kids and a meal that somebody has prepared for us.

“I can’t believe that all these years I’ve been driving by that place you’re describing and I’ve never stopped to look.”

At least one person digs through the trash can outside Warner’s office window every day. Men and women approach drivers at stoplights nearby. Maybe they’re homeless; maybe they’re not. But they’re a few feet away from the car window, asking for money.

“Do you want to know what I do?” Warner says. “Nothing.”

While serving as a deacon at Mount Sinai Baptist Church in DC, he used to spend the afternoon of the first Sunday of every month leading Communion services. When he took a break to eat, he was always approached by at least one person.

If you’re well enough to stand there and ask me for something, he’d think, you’re well enough to work.

“Are you hungry?” he’d say. He didn’t want to hand them $5 because he knew that wouldn’t fix anything. He wanted to start a conversation: “If you’re hungry, we can go get something to eat.”

Fewer than half said yes and walked with him to McDonald’s. “Why are you here?” he’d ask. “What’s going on?” Many told stories about addiction or mental illness and a fear of living life any other way. Most of the men who approached him said they didn’t want lunch, just the money.

Now, he says, he’s jaded.

“Normally, people are working off guilt when they hand them money,” he says. He’s heard of people giving out gift cards. “You’d be surprised how many of those get bartered: ‘I don’t want food with your $25 gift card, but I can sell it for $10 and get what I want.’ ”

Next: How you can help.

Warner’s former colleague Sharan London, who ran the Montgomery County Coalition for the Homeless for 14 years, says most people who panhandle aren’t homeless—and most homeless people don’t panhandle. A woman who walks along a median near Westfield Wheaton mall holds up a cardboard sign that reads jobless, not yet homeless, with sad faces drawn into the Os.

At last count, London says, there were 692 single adults in the county with no place to live. Social-service providers walk the streets one night every January visiting shelters and soup kitchens, trying to get a handle on how many people are homeless. In 2010, they found about 125 families, most headed by a single parent.

“In 2009, if you made minimum wage—$7.25—in Montgomery County, you had to work 168 hours a week to afford a two-bedroom apartment,” says London. “You can’t do it. It’s impossible.”

In 2009, if you made minimum wage in Montgomery County, you had to work 168 hours a week to afford a two-bedroom apartment.

Families with children aren’t turned away—there’s help for them year-round. If a shelter has no room, the county puts them up in a motel while they wait for space to open up in an emergency-, transitional-, or permanent-housing program. It’s different for single adults: They’re guaranteed a place to stay only in the winter.

“We’re serving 400 single adults in emergency shelters on March 31,” London says. “On April 1, that number goes down to 125. So we just made 275 homeless. Where are they going to go?”

When Warner got a call from a Montgomery County police officer about people living in the woods off Veirs Mill Road in Rockville, he stopped the cop before he’d finished speaking and asked him to take him there. The two walked about a mile into a wooded area near Parklawn Cemetery and found men and women cooking stew over an open fire.

It reminded Warner of Zimbabwe, where he’d traveled to do ministry and met people who walked ten miles barefoot on Sundays to get to a church that didn’t have a roof. It was there that he tasted the best rolls he’d ever eaten, made in an improvised oven. These people in the woods had figured out how to control the air flow and the temperature of the fire to slow-cook the stew.

He went back a few weeks later, and the people living there ran. “La Migra!” some yelled, mistaking Warner’s group for immigration authorities.

According to police, most homeless camps are illegal because they’re on private or government property. It’s hard to know how many there are: Two years ago, six known camps were in the Rockville police district. The adults who lived there slept, ate, and relieved themselves in a small area surrounded by trash.

The men and women Warner met were mostly undocumented immigrants, many with alcohol problems, who spoke of broken relationships with family. Some didn’t want the county’s help; others were too fearful to accept it.

Warner has been berated for ministering to illegal immigrants while working for the Montgomery County government.

“Some people have threatened to write to the bishop on me. They’ll say, ‘You’re a United Methodist elder—how can you stand for this?’ ” he says. “We think about immigration as some people who came across the border who are not supposed to be here. But the reality is: What do you do with the people who are here?”

Laura is thinking about picking up a few shifts at the pizza place where Pedro works. He’s back in the kitchen; she’d be out front. They could go to work together at 5 pm and come home together at 10:30 pm. It would be perfect, Laura says, because Ingrid could watch Isis when she got home from school. She would make the girls dinner, put it in the refrigerator, and Ingrid would warm it up. She’d make about $7.50 an hour.

“If I had to stop working or I got sick, this way she would have some experience,” Pedro says.

They’ve realized it’s the only way they can start to save money. They spend every dollar they earn. They have to start thinking about the future, they say. They’ve spoken with immigration lawyers about applying for citizenship. Ingrid, a high-school freshman, talks about medical school—Laura has heart problems, so her daughter wants to be a cardiologist.

“We’re trying to see what’s possible,” Pedro says.

Laura tells her son and daughter she wants them to do something honorable, to earn their money by the sweat on their foreheads. “My dream is to see them with their professions, to see them working, not poor or begging,” she says. “That’s my biggest dream.”

Tim Warner has plans for the spring. If the parks department can get the deer fencing up and the weather is warm enough for an early planting, he’d like to have low-income families growing their own food later this month.

He started thinking about a community garden last year when he saw his Salvadoran neighbors planting vegetables in their front yards. In other countries, he learned, if you have a few square feet of land, you plant on it and eat from it. His neighbors didn’t realize that it’s against the rules in his development to grow anything to eat and that you’re expected to keep your lawn nice and green.

The county school system is letting Warner use four acres of land behind an administrative building in Gaithersburg, next to an old African-American cemetery. It will be divided into small plots and he’ll invite people to farm there for $50 a year. He’ll ask gardening stores to donate plants, seeds, tools. This way, families who can’t afford their grocery bills can enjoy high-quality fruits and vegetables at a low cost and feel like a part of something bigger.

He’s planning to find two caretakers to help, he says. Pedro is his first choice.

This article appears in the April 2011 issue of The Washingtonian.