An eerie silence greeted journalist Russell Baker when he arrived in downtown DC on Wednesday morning, August 28, 1963.

“At 8 am, when rush-hour traffic is normally creeping bumper-to-bumper across the Virginia bridges and down the main boulevards from Maryland, the streets had the abandoned look of Sunday morning,” Baker reported in his New York Times column.

Authorities estimated that most of the 160,000 federal and city employees who worked nearby stayed home, while nearly half of businesses were closed. Twice the typical number of hotel rooms were vacant. “For the natives,” Baker wrote, “this was obviously a day of siege and the streets were being left to the marchers.”

From the start of the mobilization for the day’s event—the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom—the march’s national office took every precaution to ensure that participants complied with the principles of nonviolent protest. It sent manuals to local organizing committees explaining the goals for the march and instructing them on the process for bringing supporters to Washington.

Marchers were discouraged from traveling in private cars, and every chartered vehicle was required to have a captain to keep track of passengers, explain procedures, and take responsibility “for the welfare and discipline of their group.” Local organizers were required to report the name, address, and phone number of every marcher along with the number of vehicles departing from their city. The organizing committee in Chicago asked train captains to comfort “demonstrators who appear lonely,” and it recruited banjo players, guitarists, and a three-piece jazz combo to “combat boredom” during the 18-hour ride to Washington.

The National Council of Churches organized volunteers to prepare 80,000 box lunches and pack them into refrigerated trucks for sale in Washington. The garment and auto workers’ unions donated $20,000 for a sound system so marchers could hear the proceedings from the Washington Monument grounds—nearly a mile from the Lincoln Memorial, where the speeches would take place. “We cannot maintain order where people cannot hear,” march organizer Bayard Rustin said, explaining that “a classic resolution” to the problem of controlling a crowd was to “transform it into an audience.”

• • •

“I feel good because the Negroes are on the march and nothing is going to stop us!” yelled organizer George Johnson as he signaled the departure of 24 buses that the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) had arranged to carry nearly 1,000 passengers from New York City. Journalist Marlene Nadle recorded the scene in Harlem as marchers boarded at 2 in the morning. Nadle climbed aboard with ten other CORE members, including James Peck, a white activist who had been beaten in Birmingham, Alabama, and unemployed workers whose transportation had been sponsored by CORE.

Police estimated that 1,500 chartered buses carried marchers to the capital, in addition to scheduled routes. Organizers in New York City and Philadelphia reported that 400 buses came from each of those cities, carrying a total of nearly 60,000 marchers. Eleven came from North Carolina, ten from Boston, six from Alabama, four each from St. Louis and Atlanta, three each from Kansas City, Cleveland, Houston, and Jackson, Mississippi, and two each from New Orleans and Tulsa. One bus drove all the way from San Francisco.

Just after 8 am, the first of 32 chartered “Freedom Trains” arrived at Union Station, each carrying 1,000 people. Fourteen trains arrived from New York City. Another moved up the southern seaboard, starting in Tallahassee and making stops in Georgia and South Carolina. Two trains came from New Orleans, one from Detroit, and two from Chicago. Time magazine reported that the new arrivals looked “weary, bewildered and subdued” until their spirits were lifted by the Florida contingent, which “piled off the train singing the battle hymn of the Negroes’ 1963 revolution, ‘We Shall Overcome.’ ”

Delegations walked from New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and as far away as Alabama. One man came on roller skates from Chicago; another rode a bicycle from Los Angeles. Hundreds traveled by airplane. Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) activist Eleanor Holmes—later DC congresswoman Eleanor Holmes Norton—took the first flight out of LaGuardia after spending the night answering phones at march headquarters in Harlem.

Harry Belafonte and Marlon Brando arrived at National Airport with a delegation of 30 show-business people from Los Angeles, while Charlton Heston and Sidney Poitier flew with a group from New York. Josephine Baker, James Baldwin, and Burt Lancaster came in from Paris.

Some marchers headed for the Capitol to seek a meeting with their representatives, and a small group went to picket Attorney General Robert Kennedy at the Justice Department. But for the most part they were content to leave the formal lobbying to labor leader A. Philip Randolph, Reverend Martin Luther King Jr., and other representatives of the Big Ten civil-rights organizations.

The official leaders received a cold reception. South Carolina senator Strom Thurmond, who had vowed to lead a filibuster against President Kennedy’s civil-rights bill, dismissed the demonstration as “unnecessary and uncalled for,” claiming that civil-rights leaders had exaggerated the extent of discrimination in the US and “distorted in the eyes of the whole world the view of freedom as it actually exists in America.”

Minnesota Democratic senator Hubert Humphrey, an enthusiastic supporter of the march, agreed that it “probably hasn’t changed any votes on the civil-rights bill,” although he insisted it was “a good thing for Washington and the nation and the world.”

Most lawmakers simply ignored the delegation. Only a few accepted the march leaders’ invitation to be introduced during the program at the Lincoln Memorial.

• • •

By 9:30 am, 40,000 people had gathered at the Washington Monument. Although a “fair grounds atmosphere prevailed,” Russell Baker of the Times noted that several Southern delegations displayed “an uncharacteristic note of bitterness.” Seventy-five activists from SNCC huddled together wearing black armbands and, Baker wrote, singing “of the freedom fight in a sad melody.” A 15-year-old boy explained that they were “mourning injustice in Danville [Virginia],” where a few weeks earlier police had attacked nonviolent demonstrators with clubs and fire hoses.

The resentment displayed by young Southerners reflected a broader undercurrent of frustration among the marchers, from every region of the country, with the refusal of so many white Americans to support even modest steps toward racial equality. “I have no faith in the white man,” the previously optimistic George Johnson said soon after the CORE caravan left New York, expressing skepticism that the march would result in passage of Kennedy’s civil-rights bill. Johnson supported CORE’s use of nonviolent civil disobedience but admitted, “As far as I’m concerned, anything done to get our rights is okay.”

Conrad Lynn—who had grown critical of the civil-rights movement since defending an NAACP chapter president from North Carolina who in 1959 advocated that black Southerners “meet violence with violence”—handed out pamphlets calling for an all-black Freedom Now Party. “If our revolt means anything,” a party activist declared, “it is our rejection and repudiation of the white liberals whom we have permitted for too long to dictate what we ask for, when, where, and how.”

The most cynical assessment came from activist Malcolm X, who later told a reporter that he traveled to Washington but ended up watching the protest on TV in a hotel room.

Adapted from “The March on Washington: Jobs, Freedom, and the Forgotten History of Civil Rights,” copyright © 2013 by William P. Jones. Reprinted by permission of W.W. Norton & Company. This selection may not be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Writing in Ebony magazine after the march, author Lerone Bennett Jr. chided journalists who “went away and wrote long articles on ‘the remarkable sweetness’ of the crowd, proving once again that they still do not understand Negroes or themselves.” What such reports overlooked, Bennett said, was the “wonderful two-tongued ambivalence” that characterized the crowd. “Many moods competed, but two dominated: a mood of quiet anger and buoyant exuberance. There was also a feeling of power and a certain surprise as though the people had discovered suddenly what they were and what they had.”

As protesters approached the Washington Monument, they were greeted by women in white dresses and blue sashes who asked them to sign pledge cards committing themselves, “unequivocally and without regard to personal sacrifice, to the achievement of social peace through social justice.”

The ushers then directed marchers to the Ellipse, where at 10 am actor Ossie Davis began a preliminary program outside the White House. Announcing that police estimates now placed the crowd at more than 90,000, Davis introduced folksingers including Joan Baez, Odetta, Bob Dylan, Peter, Paul and Mary, and the SNCC Freedom Singers.

Bayard Rustin had recruited a contingent of National Association of Letter Carriers (NALC) activists to form a barrier to protect performers from the crowd. He later asked the trade unionists to go reserve seats for members of Congress and other guests at the Lincoln Memorial, but as they departed he noticed that others were following them with the hope of getting a seat. “My God, they’re going!” Rustin cried as he rounded up Randolph, King, and other leaders who had just returned from Congress. “We’re supposed to be leading them.”

A contingent of the Guardian Association—an organization of black police officers from New York that Rustin had recruited to serve as the event’s “internal security force”—succeeded in slowing the march and creating space for the Big Ten representatives to walk arm in arm behind a truck carrying TV cameras, but the leadership was still surrounded by “oceans of bobbing placards.” One of King’s staffers remarked, “A revolution is supposed to be unpredictable.”

With its chaotic start, the march displayed the spectrum of emotions that protesters brought with them. “Some marchers wept as they walked,” Time reported, adding that “the faces of many more gleamed with happiness.” A group of young people from Louisiana danced the entire way.

“What’s after college for me?” asked a sign carried by a ten-year-old boy. Several groups guided coffins symbolizing the death of Jim Crow. Even the official signs displayed a wide array of concerns: “An End to Bias,” “Jobs for All,” “Integrated Schools,” “Decent Housing,” “Voting Rights,” “Higher Minimum Wage Coverage for All Workers.”

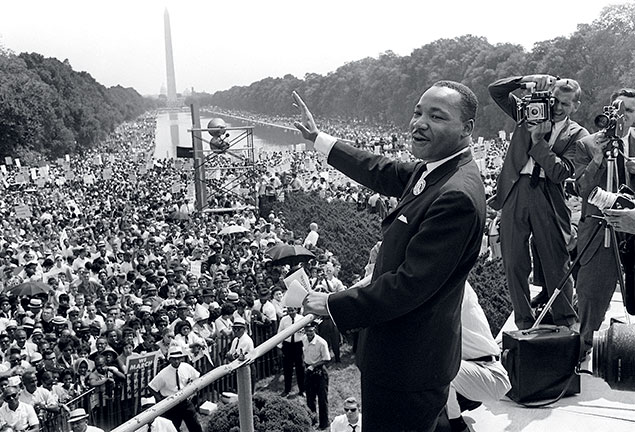

Having swelled to more than 200,000, the march’s two streams converged into a broad semicircle around the Lincoln Memorial and pushed back on both sides of the Reflecting Pool and all the way back to the Washington Monument.

New York City mayor Robert Wagner walked down the steps of the memorial while Jackie Robinson, who had integrated Major League Baseball two decades earlier, found a seat with his son David. Ossie Davis reclaimed the microphone and began introducing the celebrities.

Singer Josephine Baker, who had vowed never to return to the US after being denied service in a New York nightclub, said, “I’m glad that in my homeland, where I was born in love and respect, I’m glad to see this day come to pass.” Comedian Dick Gregory joked that the last time he had seen so many black people was in a Birmingham jail.

• • •

By 2 pm, marchers were fading in the heat. Some sought shelter under the trees or wandered off, but they were drawn back to attention by the arrival of Randolph, King, and other leaders. Ossie Davis asked people at the back to stop pushing forward, as those in front were getting crushed. Red Cross volunteers distributed ice and started carrying away those overwhelmed by the heat.

Randolph came to the microphone and, looking out over the crowd, declared: “We are gathered here today for the largest demonstration in the history of this nation. Let the nation and the world know the meaning of our numbers.”

Trained in the speaking style of a pre-television era, the 74-year-old Randolph appeared as if he were conserving his energy for a two-hour speech before a union convention. Marchers responded with polite applause. Despite his start, Randolph won over the crowd with the boldness of his message. Emphasizing that the “civil-rights revolution” was “not confined to the Negro” or even “to civil rights,” the labor leader insisted that “we know that we have no future in a society in which 6 million black and white people are unemployed and millions more live in poverty.”

History, he said, had placed African-Americans “in the forefront of today’s movement for social and racial justice, because we know we cannot expect the realization of our aspirations through the same old anti-democratic social institutions and philosophies that have all along frustrated our aspirations.” But as he had since his days stumping for Eugene V. Debs nearly half a century earlier in Harlem when Debs was the Socialist Party’s presidential candidate, Randolph insisted that African-Americans were not the only ones with a stake in that revolution: “The March on Washington is not the climax of our struggle but a new beginning not only for the Negro but for all Americans who thirst for freedom and a better life.”

By that point he was faltering and repeating his words, but the audience roared when he defended the tactic of mass mobilization: “The plain and simple fact is that until we went into the streets, the federal government was indifferent to our demands.”

• • •

Few knew it at the time, but one of the next speeches had been the subject of intense debate among march leaders.

The evening before the event, SNCC activists had circulated a draft of the address that their 23-year-old chairman, John Lewis—today a congressman from Georgia—planned to deliver. Drafted with several leaders of the group and Rustin aide Tom Kahn, the text captured the spirit of young radicals who had been risking their lives on the front lines of struggle in Southern states. Denouncing Kennedy’s civil-rights bill as “too little and too late,” Lewis planned to point out that it did nothing to “protect our people from police brutality,” to protect the right to vote, or to “ensure the equality of a maid who earns $5 a week in the home of a family whose income is $100,000 a year.”

Lewis’s speech echoed Randolph’s reference to a “civil-rights revolution,” which the elderly trade unionist had used repeatedly in his speeches to the NALC and other groups. “The revolution is at hand,” Lewis planned to say, “and we must free ourselves of the chains of political and economic slavery.”

But it also employed violent imagery that Randolph had always insisted was counterproductive. “We will march through the South, through the heart of Dixie, the way Sherman did,” the SNCC document read, referring to the Union general who had burned cities and destroyed crops in Georgia at the end of the Civil War. “We shall pursue our own ‘scorched earth’ policy and burn Jim Crow to the ground,” the text read, adding that all this would be done “nonviolently.”

Randolph had spent much of the previous 24 hours mediating between Lewis and other leaders about the SNCC speech. He dismissed Washington archbishop Patrick O’Boyle’s complaints about “communist” language such as “revolution” and “masses,” stating, “I’ve used them many times myself.” Randolph took more seriously the objections of union head Walter Reuther and others who argued that such harsh criticism would make it impossible to strengthen and pass the civil-rights bill, which remained one of the mobilization’s central objectives. Randolph also agreed with Rustin and King that SNCC’s references to violence, even as metaphor, violated the Gandhian spirit that had inspired the march.

Rustin and Lewis worked through much of the night discussing alternatives, and Randolph convinced the SNCC leader to accept them. “I’ve waited all my life for this opportunity,” Lewis later recalled the aged radical pleading, nearly in tears. “Please don’t ruin it.”

The incident was seen by some as further evidence that white liberals had co-opted the march, but after dropping explicit references to violence and agreeing to support Kennedy’s bill with “great reservations,” Lewis and other SNCC activists felt “our message was not compromised.”

He still reminded marchers that they were “involved in a serious social revolution,” and he denounced a political system based on “immoral compromise” and dominated by “political, economic and social exploitation.” Media carried detailed accounts of the debate, even comparing passages from both versions of the speech, so the controversy drew far more attention than Lewis might otherwise have received.

“He finally gave in,” Time reported, “but not much.”

• • •

What was most remarkable about Lewis’s message was how consistent it was with the other speeches—not just Randolph’s but also those of the more moderate leaders.

“I am here today with you because with you I share the view that the struggle for civil rights and the struggle for equal opportunity is not the struggle of Negro Americans but the struggle for every American to join in,” white union leader Walter Reuther declared, echoing Randolph’s appeal for an interracial struggle for both racial and economic justice.

While he called Kennedy’s civil-rights bill “the first meaningful step,” Reuther reiterated Lewis’s complaint that it didn’t go far enough. “The job question is crucial,” he insisted, “because we will not solve education or housing or public accommodations as long as millions of American Negroes are treated as second-class economic citizens and denied jobs.”

CORE chairman Floyd McKissick read a letter from his colleague James Farmer, who had been scheduled to speak but refused to post bail after he and 200 other activists were jailed for protesting segregation in Louisiana. “We will not come off of the streets until we can work at a job befitting of our skills in any place in the land,” McKissick read. “We will not stop our marching feet until our kids have enough to eat and their minds can study a wide range without being cramped in Jim Crow schools.”

National Urban League director Whitney Young urged marchers to help transform “the rat-infested, overcrowded ghettos” into “decent, wholesome, unrestricted residential areas,” to address racial disparities in infant mortality and life expectancy, and to integrate and provide funding to “congested, ill-equipped schools which breed dropouts and which smother motivation.”

The NAACP’s Roy Wilkins leveled a scathing attack at the White House, asking how it was possible that the government could not protect civil-rights activists from being “beaten and kicked and maltreated and shot and killed by local and state law-enforcement officers” and calling Kennedy’s civil-rights proposals “so moderate an approach that if it is weakened or eliminated, the remainder will be little more than sugar water.”

• • •

By the time Martin Luther King Jr. came to the stage, it was nearly 4 pm, and some marchers had already headed back to Union Station so they wouldn’t miss their trains. When Randolph introduced the young minister, he got only as far as “the leader of the moral revolution” before the crowd erupted into applause.

King began with a scripted speech that emphasized the links between economic justice and racial equality. “In a sense we’ve come to our nation’s capital to cash a check,” he stated, pointing out that 100 years after Lincoln had freed the slaves, their descendants were “still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation” and restricted to “a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity.”

Halfway into the prepared text, however, he pushed his notes aside and delivered an improvised version of the refrain he had pioneered at the AFL-CIO convention in 1961 and elaborated in other settings before delivering it at the Detroit “Walk to Freedom” a month before the March on Washington.

“So even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream. I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the meaning of its creed: We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.”

The audience roared.

Looking to a day when “the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave-owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood” and expressing a messianic confidence that “the rough places will be made plain, and the crooked places will be made straight and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed,” the preacher delivered a much-needed respite to marchers who had endured a long day of intense political engagement.

Ending with a picture of “that day when all of God’s children—black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics—will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual, ‘Free at last, free at last, thank God Almighty, we are free at last!,’ ” King emanated an optimism that brought even the most hardened and cynical SNCC activists to their feet, wiping tears from their eyes.

• • •

Close to 5 pm, the march ended with a benediction by Benjamin Mays, Martin Luther King’s mentor from Morehouse College.

Exhausted, marchers boarded shuttles or began walking back to buses, trains, planes, and cars. The sound system blasted “We Shall Overcome” from an organ at the Lincoln Memorial, but most people were too tired to sing along.

By sundown, the Mall was deserted, save for the team of 400 city employees charged with picking up garbage, dismantling stages, and hauling away the portable toilets. Rustin had offered to recruit volunteers to do this, but city officials seemed eager to get the crowds out of town. Organizers of the march were happy to oblige. “We’ve got to get back home and finish the job of the revolution,” CORE’s Floyd McKissick declared.

McKissick in fact had one final duty to perform before leaving Washington, and with Randolph, Rustin, King, and other leaders he climbed into a shuttle for the short ride to the White House.

President Kennedy congratulated them for keeping order and sending a clear message to Congress but, in his excitement, seemed to have forgotten that his guests had been working since early that morning.

“Mr. President, I wonder if I could have just a glass of milk,” Randolph asked, and Kennedy sent for refreshments before they settled into a 60-minute conference with Vice President Lyndon Johnson, the Secretary of Labor, and the head of the Civil Rights Division of the Department of Justice.

Afterward, Kennedy joined the leaders for a press conference, where he vowed to continue his work toward “translating civil rights from principles into practices” and promised to expand that struggle to ensure “increased employment and to eliminate discrimination in employment practices, two of the prime goals of the march.”

Echoing Randolph’s insistence that such policies would benefit Americans of all races, Kennedy declared that the March on Washington had advanced the cause of 20 million African-Americans, “but even more significant is the contribution to all mankind.”

This article appears in the August 2013 issue of The Washingtonian.