Around 9 in the morning on a July Friday, Carol Fennelly leads her flock through the entrance drill at Western Correctional Institution, a maximum-security prison in Cumberland, Maryland, where the state is squeezed by West Virginia and Pennsylvania.

They have the routine down: Present identification, step through the metal detector, wait for a guard to stamp your hand and put an orange wristband on you, then find a seat in the waiting room. Nobody steps out of line, but because for most of them today marks the last visit until next summer, almost everyone is eager to get inside.

Fennelly doesn’t allow her assembly to walk through the prison. So once the whole group has hand stamps and is through to the waiting room, they’re escorted around the side of the building, along a wall of razor wire and into the prison’s library. Even then, they show none of the ordinary restlessness you’d expect of children, which is what nine of Fennelly’s charges are. Their dads live here.

The remaining nine are staff members of Fennelly’s organization, Hope House, which runs Camp Hope. The new art teacher, Cait Engels, helps the campers and their fathers draw pictures of things they’d love to do together, if—though they say “when”—the fathers are released on parole: fishing, playing basketball, visiting the Bahamas.

There’s also Tyron Jessie, a former camper who monitors the boys’ bunks at the nearby campsite and helps keep the mood light—he’s funny, and he’s been there. Brenda Marbury (she’ll greet you with a hug and ask that you call her Miss Brenda) is Fennelly’s right hand, who manages logistics and monitors the campers’ gallon-size Ziploc of scissors, which the staff gets to bring in, provided they’re counted and recounted throughout the day. If one goes missing, all efforts focus on searching the room until it turns up.

“It takes a certain level of courage for a warden to let us in here with our contraband,” Fennelly jokes, waving a pair of scissors. “Everyone knows we can’t let anything go wrong. That would be the end.”

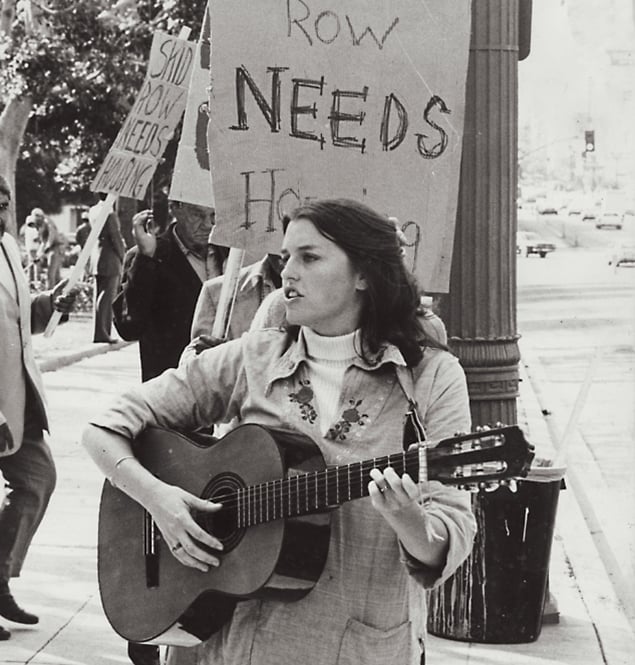

Fennelly’s activism was once the stuff of more drama. Thirty years ago this month, she and longtime partner Mitch Snyder were at the center of a clash with the Reagan administration that ended in a hunger strike, attended by 60 Minutes, that helped put homelessness on the national agenda. Hope House may be inspired by the same ideals of faith and social justice, but today Fennelly is consumed by the details that change a few lives in big ways.

• • •

Kobe Goodall has been to Camp Hope three times. His father, Carlos, trains puppies at the prison to become veteran-assistance dogs. “I just enjoy spending time with my child,” Carlos says. “I wouldn’t change a single thing about this. It’s perfect.”

Kobe agrees on all but one point: “Being able to see my dad for five hours a day is my favorite thing about this, but leaving sucks.”

Not all Camp Hope families are as in tune. Some children talk to their fathers on the phone or videoconference regularly; others don’t. The rare child who visits WCI outside of camp isn’t allowed to touch his dad on those visits.

But camp is casual and friendly. Hugs are encouraged, and activities feel like play time in a school cafeteria. The tile floors, inmate-made paintings on the windows, and horrible food feel familiar. The singing, dancing, art projects, bonding time, and opportunities to reflect make most days at WCI feel like regular days for the kids. But when something goes wrong—such as the time a couple of years ago when scissors actually did go missing—the kids are reminded exactly where they are. WCI is a terrifying building, and many who live there, including several of the campers’ dads, have done unimaginable things.

But for Fennelly, 65, who has been running her camps for nearly 15 years, prisons are where something like home happens. When she decided to find a place to retire, she bought a cottage in West Virginia about an hour from FCI Cumberland, the town’s other correctional institution, which she says is her favorite prison.

• • •

Home is complicated for Fennelly, who spent almost two decades working, living, and raising her children with the homeless. Forty years ago, the California mother of two was wading through the breakup of a troubled marriage when she heard a call.

“It’s pretty mystical and crazy-sounding,” she says. “I was putting clothes away in my kids’ room when this light sort of came on. Then I heard a voice say God had something special for me to do.” What precisely, the vision didn’t say, other than it would involve moving away from her husband. “Of course,” says Fennelly, “I immediately thought I’d lost my mind and went back to him instead.”

When the marriage eventually failed, she decided to start over in Washington. A few months earlier, Reverend Jim Wallis, an evangelical minister, had spoken to a class in “radical discipleship” that Fennelly was attending at her church. Wallis, who would write God’s Politics and other bestselling books that helped inspire a religious-left resurgence in the mid-1990s, was then known as the founder of Sojourners, a social-justice organization headquartered in Columbia Heights. In late 1976, Fennelly moved to Washington with her son and daughter and began working with Wallis and Sojourners.

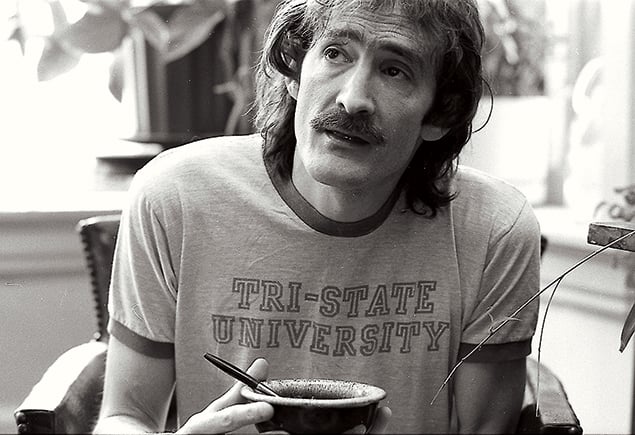

She met Mitch Snyder at a party celebrating a campaign Sojourners had run with the Community for Creative Non-Violence, an anti-war group that, post-Vietnam, had become focused on poverty. A charismatic, driven activist, Snyder was a veteran and a petty criminal who’d been radicalized in prison by two Catholic priests and brothers, Philip and Daniel Berrigan, who were serving time for burning files they’d stolen from a Maryland draft-board office. CCNV’s de facto leader, Snyder was infamous for his passionate opposition to the Vietnam War.

Fennelly had seen pictures of Snyder and had spotted him at a picket line weeks earlier but had been too intimidated to speak to him. At the party, she saw him go outside and followed him. “I asked if I could bum a cigarette even though I didn’t smoke,” she says. “He was smoking Pall Malls, to make it worse. I just loved him.”

Fennelly soon joined Snyder at CCNV, and the two became a power couple of the indigent—organizing rallies, hunger strikes, letter-writing campaigns, and other demonstrations, demanding social services for the homeless. Fennelly moved with her kids into CCNV’s Columbia Heights headquarters. (Today her son, James Fennelly, is a vice president at Jair Lynch, a real-estate development firm focused on neglected DC neighborhoods. Her daughter, Carrie Kohns, formerly DC mayor Adrian Fenty’s spokesperson and chief of staff, is chief of staff to Congresswoman Karen Bass, a California Democrat.)

By 1984, Snyder had become a leader in the national movement calling attention to the explosion in the homeless population. That autumn, he plunged into a 51-day hunger strike, aimed at forcing the Reagan White House to finish converting an abandoned University of the District of Columbia building near Union Station into a shelter. (See sidebar.) Snyder’s fast generated national headlines as Reagan’s “morning in America” reelection campaign was hitting its home stretch. In early November, Reagan gave in. The Federal City Shelter became a model, and it remains one of the largest and most comprehensive facilities of its kind in the country, with beds for 1,350 people.

The victory was the couple’s shining moment, memorialized two years later in a TV movie, Samaritan, with Martin Sheen as Snyder and Chicago Hope actress Roxanne Hart as Fennelly. Snyder’s personality, however, became increasingly erratic. The conviction and volatility that had moved a presidential administration funneled into irrational behavior and depression. In 1990, Snyder hanged himself in the shelter located on a block that today bears his name.

• • •

After years of civil disobedience, Fennelly’s lengthy arrest record made her mostly unemployable. When she left CCNV after four years of trying to fill Snyder’s shoes, she went back to working for Wallis, who was just beginning his effort to raise an alternative Christian voice to Ralph Reed and the religious right. WAMU, capitalizing on her local celebrity, hired Fennelly as a political commentator.

Three years later, Congress passed the National Capital Revitalization and Self-Government Improvement Act of 1997, which gave DC until 2001 to close Lorton prison in Fairfax County—home to more than 7,000 inmates from the District—and mandated that they be absorbed into federal penitentiaries. Shortly afterward, a friend called Fennelly, she recalls, “to talk about what relocation to God-knows-where would mean for their families.” She promised to find out.

What Fennelly learned was that many Lorton prisoners had been moved to Youngstown, Ohio, a five-hour drive that would make visiting a hardship for already struggling families. In 1998, she sold her house, registered a 501(c)(3) organization, and moved to Youngstown. The day before Thanksgiving 1999, Hope House hosted its first father/child teleconferences, connecting two church basements full of children in Southeast DC and Shaw with the Northeast Ohio Correctional Center, pre-Skype, via a Microsoft program called NetMeeting. “Often we were able to run video but not sound,” Fennelly recalls, “or they’d talk but couldn’t see each other move.”

Conversations were monitored on the kids’ end by Fennelly and on the prisoners’ end by guards. And despite the inconveniences of the stone-age internet, the response from dads and kids was overwhelmingly positive. “All these men, who usually feel completely written off as fathers, were just so grateful,” says Fennelly.

The prison quickly saw the value as well. “I went expecting a fight,” she recalls. “But the administration, which was having some real struggles, was anxious to get some creative programming in to settle things down.”

In 2001, the prison in Youngstown was shuttered, and Fennelly tracked its DC inmates to North Carolina and Cumberland.

“Initially I was skeptical,” says WCI’s warden, Richard Graham, who first saw Camp Hope in action at Cumberland’s maximum-security facility. But today he calls the camp “a valuable tool.” Says Graham: “Some men had not seen their children in years, and it was a very structured reintroduction to re-establishing that relationship.”

With the prisoners closer to DC, Fennelly moved her operation to Washington, where she was also closer to a network of private donors and foundations—she had founded the program largely out of her own bank account.

Now Fennelly and Miss Brenda run its operations from a house in Fort Totten. Hope House runs similar programs at two other prisons. She targets those with high concentrations of inmates from the District, working with the Bureau of Prisons to determine which wardens will be receptive. (Three other prisons host camps based on her model.) When camp isn’t in session, Hope House hosts teleconference sessions and delivers video recordings of fathers reading books to their kids.

But the highlight of the year is camp week, despite the limited time and resources. To an outsider, it’s a sobering experience, watching a murderer stand in front of a group of kids and cry as he tells his son how their first week together after two years apart has taught him so much. He promises to be a better dad, despite doing something so awful he’ll never be eligible for parole. Nobody wins, really, but everyone is better off. If Camp Hope’s resources are limited, they seem boundless compared with those of a man in a maximum-security prison.

“You’ve opened doors for my son that I could never open from here,” Carlos Goodall, the veteran camp father, said to Fennelly as the week wrapped up in July. “We need this. And the kids need this. We’re just so grateful.”

A Year of Miracles

Carol Fennelly remembers the fast that changed how DC shelters its homeless.

The Community for Creative Non-Violence was being evicted from a location near the National Portrait Gallery, and we needed a new place to do soup-kitchen work. One of our community members, Justin Brown, found an old UDC building at Second and E, Northwest, that the General Services Administration had up for auction. Obviously, we didn’t have the means to buy the place. But Susan Baker, wife of President Reagan’s chief of staff, Jim Baker, was very attuned to the issue of homelessness. With her help, we convinced the feds to give us use of the building and negotiated for them to make it habitable.

That was December 23, 1983, but the feds said they needed six weeks. It was one of the coldest Christmases on record—three degrees, with snow. So we held a press conference in front of the building that day, saying: “How can we let all these people live on the street? Can anybody help?”

Around 10 o’clock that night, we got a call from real-estate king Oliver Carr, offering us the Hotel Presidential. He was going to tear it down, so it was empty, and he told us we were welcome to it. “But there’s one thing,” he said. “Each room had a window air-conditioning unit that’s been removed. Those holes need to be boarded up.”

From the minute he offered the hotel, it was like magic: We got cots from the military. Edwin Hoffman at Woodward & Lothrop dropped off blankets. This amazing French restaurant gave us black-bean soup.

CCNV had a Christmas Eve party every year, with singing and dancing and poetry readings, and we gave out gifts. Hundreds of volunteers were already in town for that. We sent half of them to board up windows while the others got ready for the party. Afterward, we somehow got everyone to the Presidential. Everyone who needed a place to stay had their own room and bathroom that night, and there were enough donations for weeks. It really was a Christmas miracle.

We left the hotel in early 1984 and moved into the UDC building, now the Federal City Shelter. The assumption was we’d leave in the spring, but the idea of putting the homeless back on the street wasn’t something we could deal with. We decided we weren’t going to leave.

Lucky for us, it was an election year. Everyone knew Reagan would win a second term, but there was more press scrutiny than normal. We talked about marching everyone out of the shelter to sleep outside the White House, but that was a bad idea—we had a lot of them at CCNV. We planned a civil-disobedience campaign, but people getting arrested wasn’t enough.

So a group of us decided to fast. Mitch was on water only. I was on liquids at first and then just water at the end. Several others did the same. I mostly remember being gaunt, and so tired, but Mitch got pretty sick. People thought he was preparing to die for the shelter. News outlets started paying attention; 60 Minutes did a segment.

After 50 days, on the eve of the election, Mitch and I were on the phone all day and all night with the Secretary of Health and Human Services, Margaret Heckler. If Mitch agreed to eat, the administration would fund a renovation. I remember how wired Mitch was over the idea that Reagan had caved. Absolutely wired.

Change didn’t happen overnight. But over time, we got our strength back and the administration renovated the shelter, which is still one of the largest of its kind in the world. It really was a tremendous thing.

This article appears in our December 2014 issue of Washingtonian.