It was the first warning of the nightmare ahead: On July 3, 1981, the New York Times reported on a rare form of cancer affecting gay men. “Eight of the victims died less than 24 months after the diagnosis was made,” the article said. The Centers for Disease Control noted that no cases had occurred in women or heterosexual men.

The news shook Washington’s gay community. Some read the article over morning coffee in their Capitol Hill offices. Others heard about it during power lunches on K Street. The illness became a hot topic at the bars near Dupont Circle.

Yet no one could have fully grasped what the Times article foreshadowed. “Nobody read this story and thought this was the end of life as we knew it,” says Michael Manganiello, who works in health policy. The next year, the CDC gave the disease a new name: acquired immune deficiency syndrome—or AIDS.

As the epidemic unfolded, Washington became a focal point for activists demanding a stronger response from the federal government and the medical community. The disease devastated many who lived here—not just gay men but women and straight men as well, including many who had been infected through intravenous drug use.

Today DC has the highest HIV/AIDS infection rate in the country, on par with many parts of Africa and only slightly below the peak infection rate of San Francisco in 1992. What follows is a look back on 30 years of AIDS, in the voices of many who were—and still are—most directly affected.

“I Had the Symptoms”

Initially, AIDS wasn’t as visible in Washington as in San Francisco and New York City. But that changed as the number of people with the disease grew.

Sean Strub (founder of several publications and Web sites, including Poz, a magazine for HIV-positive people): “I felt numb inside when I was reading the New York Times article. I had the symptoms: night sweats, weight loss, swollen lymph glands. I just knew it had something to do with me.”

Hilary Rosen (a political consultant who was the first lobbyist for the Human Rights Campaign Fund): “The early publicity was about New York and San Francisco. The guys who’d been to those two places were thought to be the ones at risk. Then Washingtonians who were in political jobs or worked with political figures started to be diagnosed. You couldn’t separate the shame of being gay from the shame of being diagnosed.”

Riley Temple (Lawyer and activist): “It seemed as if AIDS was nascent in Washington. Then suddenly it was everywhere.”

Sean Strub: “When the epidemic hit, a community emerged in New York City. It was different in DC—it was smaller and built around the Whitman-Walker Clinic. I remember DC being very closeted and gossipy.”

Lou Chibbaro Jr. (Washington Blade reporter): “AIDS became a main beat for us. We even had a section of the paper called AIDS Digest. We reported news about AIDS that the mainstream press wasn’t focusing on.”

“I Thought of Them as Ghosts”

By the end of 1985, the CDC reported almost 16,000 AIDS cases nationally, up from 452 in 1982.

Dr. Jane Delgado (president of the National Alliance for Hispanic Health): “I came to Washington because my best friend since I was 16 lived here. He was the first person I knew who got sick, and I took care of him until he died. People didn’t want to be in the room with him. They didn’t want to bring him food. A frustrated doctor said to me, ‘I went into infectious diseases because you can treat them. If I’d wanted to see people die, I’d have gone into cancer.’ ”

David Messing (Whitman-Walker board chair): “In the ’80s and early ’90s, when you got a diagnosis of AIDS, it was a death sentence. I remember visiting my friend Walter Owen in the hospital and having to wear gowns, latex gloves, and face masks.”

Septime Webre (artistic director of the Washington Ballet): “I remember carrying my best friend down the steps to his parents’ Suburban so they could take him home to Texas to die, which he did six weeks later. Toward the end, he went blind. I went to the funeral. His father was a prominent businessman in town. It was a Baptist service, and no one would mention AIDS.”

David Messing: “I’d be out shopping or doing errands and see people I came to think of as ghosts, wasting away and covered in Kaposi’s sarcoma lesions. I’d recall what they looked like when they were healthy, handsome men. I’d see them in a social setting looking well, and two months later they were walking with canes, 50 pounds lighter.”

David Mixner (civil-rights activist): “There was one two-year period when I did over 90 eulogies for friends under the age of 40. It was funerals every Saturday.”

Richard McCann (American University literature professor, coeditor of Things Shaped in Passing): More ‘Poets for Life’ Writing From the AIDS Pandemic: “Those times were simultaneously medieval and modern. It was like living through the black death of the Middle Ages, but you also went home and had a Mr. Coffee and a microwave.”

John Berry (director of the Office of Personnel Management, the highest-ranking openly gay official to serve in the executive branch): “When I met my first partner, Thomas Leishman, I fell in love at first sight. On our first date in 1985, Tom said, ‘I’m going to tell you something, and if you have any qualms I’ll understand, but I have this disease.’ I remember thinking this would be a really stupid reason not to love somebody, and that’s what I said. In June of 1996, he passed away at age 37. From 198 pounds of solid muscle, his weight at death was something like 83 pounds. I saw firsthand the cost of this.”

“I Couldn’t Tell Anybody”

There were no laws to protect HIV/AIDS patients from discrimination, and many lost jobs, homes, and relationships. In 1985, Ryan White, a teenager from Indiana, was barred from school because he had AIDS. That same year, actor Rock Hudson died, giving a more public face to the epidemic.

Wallace Corbett (AIDS advocate): “I was first diagnosed in 1988 and soon entered a vaccine trial at Georgetown University Hospital. Everything was anonymous. I was scared. I couldn’t tell anybody. My partner had just died. I wanted to live. I was 28 years old.”

David Messing: “I knew a lovely young man named Patrick who was diagnosed with AIDS and lost his job and apartment. He died at age 23 after an experimental cancer treatment at NIH. His body just couldn’t take the assault.”

Patricia Nalls (founder of the Women’s Collective, a DC nonprofit for girls and women with HIV/AIDS): “In 1987, my husband and daughter died of AIDS and I was diagnosed HIV-positive. Services for women were nonexistent. I thought I was the only HIV-positive woman in Washington.”

Imani Woody (LGBT advocate): “I was so angry when my brother David passed away from AIDS at age 25 in 1994. He was so good-looking, like a young Sidney Poitier. At his funeral, the minister preached about how people needed to ‘get right with God’ and ‘live a different lifestyle.’ I got up and walked out.”

Don Blanchon (Whitman-Walker executive director): “Whitman-Walker had one of the first AIDS-specific dental and eye clinics, because dentists and eye doctors were reluctant to care for AIDS patients. ‘What if I get blood on me during a dental exam? What if someone coughs on me during an eye exam?’ ”

Patricia Nalls: “There was discrimination for women, too. I looked a certain way, I was married, with a home and children. I didn’t fit the stereotype. People try to put you in a different box. Drug-user box. The sex-worker box. Promiscuous box. As if an everyday woman doesn’t get HIV.”

David Messing: “Even funeral homes were afraid to take people who had died of AIDS. Richard Rapp operated a crematorium in the Maryland suburbs and saw that there was a need for compassionate service. I called him when my friend Walter died, and he provided the services with a great deal of humanity.”

Elizabeth Taylor Steps In

President Ronald Reagan didn’t condemn AIDS sufferers as televangelist Jerry Falwell and Senator Jesse Helms did, but he avoided discussing the disease. On September 17, 1985, Reagan mentioned AIDS publicly for the first time at a White House news conference.

At the request of actress Elizabeth Taylor—who was chair of the American Foundation for AIDS Research (amfAR)—Reagan spoke at a fundraiser for the organization in Washington in May 1987. He announced the creation of a national commission on HIV/AIDS and called for education and compassion. But he was booed after calling for routine testing—which most AIDS activists opposed for fear of discrimination—and for denying residence to HIV-positive immigrants.

Sean Strub: “With Reagan, there was intentional neglect. Jesse Helms and Jerry Falwell had just come into prominence, so there was all this anti-gay sentiment: This was nature doing its housecleaning.”

Riley Temple: “Elizabeth Taylor is the one who finally got Reagan to address AIDS. She went to Nancy Reagan and appealed to the President’s moderate side. Taylor was a cultural icon, someone they knew, and they could no longer turn their face away.”

Jim Graham (DC Council member and former head of the Whitman-Walker Clinic): “So many celebrities made commitments to AIDS. But the depth of Taylor’s commitment was extraordinary. [When Whitman-Walker named its treatment facility in Taylor’s honor], she came to town in 1993 for the dedication. She told me that Ronald Reagan had a lot of friends who were sick and had died. She couldn’t understand why he was silent for so long.”

“The Darkest Part of My Career”

On April 23, 1984, Health and Human Services Secretary Margaret Heckler announced that Dr. Robert Gallo of the National Cancer Institute had isolated the virus that caused AIDS. But her prediction that a vaccine would be “ready for testing in approximately two years” was, she later admitted, a serious miscalculation.

In 1985 an AIDS test became available, and in 1987 the first AIDS drug, azidothymidine (AZT), was approved by the Food and Drug Administration. But the medication had serious side effects and couldn’t stop the virus from mutating and developing resistance.

Dr. Anthony Fauci (director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases): “It was the darkest part of my career. The median time [of life remaining] from when someone came into a hospital was about 27 weeks. The only people who came in were very advanced [cases].”

Dr. Thomas Qualey (local physician): “It was very difficult to find any effective treatments because the AIDS virus is an extremely complex microbe, capable of mutating and replicating rapidly and effective at decimating the only defense our bodies can use against it: our immune systems. I saw men who should have been in the prime of their lives, in their twenties and thirties, emaciated and holding IV bags as they lay on the beach at Rehoboth. It was like a nightmare.”

Dr. Jane Delgado: “People thought we didn’t know what we were doing. They were right. We didn’t know much about the immune system, period.”

Nancy Tucker (first coeditor of the Gay Blade, which became the Washington Blade): “Men were dying everywhere. No one had an idea of how this could be cured. It was as if the great gay life was over as soon as it started—as if everyone had to pay for ten years of [post-Stonewall riots] freedom.”

Jim Graham: “Whitman-Walker Clinic had the first testing program [in the Washington area]. I was test number one. I wanted to show that this was important. It was controversial at the clinic. First, why would you want to know? There was no prospect of any cure, no medication, no vaccine. Just practice safe sex and let it go. Second, there was stigma and fear of being found out.”

Patricia Nalls: “Women avoided getting tested and treated because they didn’t think they were high risk, or they had other priorities like family.”

Imani Woody: “Desperate people were looking for alternative treatments anywhere they could find them. I remember when word spread like wildfire in DC’s African-American community, there was a doctor here from Africa who said he had a cure. It sounded bogus, but people wanted to believe, so they flocked to him. There are so many stories like that from the ’80s and ’90s.”

The Quilt

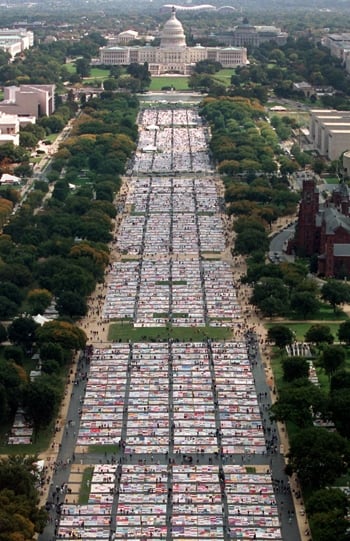

Displayed on the Mall for the first time in 1987, the AIDS Memorial Quilt included 1,920 panels honoring those with AIDS who had died. Half a million people visited the quilt in its first weekend on the Mall.

Bob Witeck (business leader and LGBT advocate): “My first impression was its vast size and beauty as public art. Then I read the emotional messages on panel after panel. The most powerful was seeing the panel for a friend of mine. When I saw Greg’s name boldly printed, I remembered his parents’ shame and fear. They refused to tell family and friends the cause of his death. Now with his life honored on the quilt for all the world to see, it was impossible for anyone to ignore, forget, or feel ashamed.”

Michael Manganiello: “I saw people huddled, weeping, and staring off into space. It was one of the most effective ways to communicate to the general public what a nightmare we were living through. You could get a sense of someone’s entire life in a quilt panel.”

Hilary Rosen: “I counted 35 friends.”

Ronald Johnson (vice president of policy and advocacy for AIDS United; HIV-positive since 1989): “I visited the quilt in 1996, the last time it was displayed in its entirety on the Mall. I had the opportunity to read aloud the name of my partner, who’d died a year before, in addition to other names. Right after I finished and by sheer fluke, I ended up walking by the panels of the names I’d read. I just started crying.”

“I Wanted to Do Something”

People looking for ways to channel their grief and anger found an outlet by volunteering.

Ron Simmons (CEO of Us Helping Us, People Into Living, a black AIDS-services organization in DC): “A few months after I tested positive, I saw a flyer for an Us Helping Us meeting, billed as a meditation and support group for HIV-positive African-American men. On my birthday—March 2, 1991—I walked into [founder] Rainey Cheeks’s one-bedroom apartment on E Street in Southeast DC and saw 22 other HIV-positive African-American men. I felt at home. They taught me I could live with this disease, and no other black organization was saying that.”

John Berry: “I got involved with Gift of Peace House in Northeast DC, which the nuns of Mother Teresa opened for people with AIDS to die with dignity. Mother Teresa herself came one day. She looked around and thought it wasn’t clean enough, so she said, ‘Buckets. Everybody get a bucket.’ We all scrubbed the floor together. Marion Barry was the mayor, and he came along with television cameras. We were all on our knees scrubbing. Barry walked in, and you could see he didn’t know what to do. Mother Teresa looked up, smiled at him, and said, ‘Dear, you’ll be a lot more useful if you get down here.’ Clearly the mayor was thinking, ‘I’m in a nice suit—I didn’t come prepared for this.’ But he got down on his knees and scrubbed the floors with the rest of us.”

Janice Horner (former volunteer lay chaplain for Inova Fairfax Hospital): “I remember being called to an AIDS patient’s room, where he was surrounded by terrified friends and family, most of whom had had no idea he was ill. The battle was playing out tragically in the suburbs—often families would face a double whammy of finding out that their child was both gay and dying.”

Patricia Wudel (executive director of Joseph’s House, a DC hospice for poor and homeless people dying of AIDS and other illnesses): “At a church service in the late 1980s, an African-American man named Ron struck up a conversation and asked me: ‘Do you want to meet my family?’ He brought me to Joseph’s House, and when I walked up the steps and opened the door, the aroma of ham, eggs, and coffee wafted out. At the dining-room table were 12 people—black, white, old, young. There was a man in a wheelchair across from me, and another man was feeding him. Outside there was so much meanness. Inside there was laughter and kindness, and I wanted to be part of it.”

“I Started to Feel Hope”

AIDS activists demanded that pharmaceutical companies provide faster access to drugs and that the federal government allocate more research funds and provide disability benefits for patients. Groups such as Act Up, started by writer/activist Larry Kramer, held angry demonstrations.

Michael Adams (executive director of SAGE, an advocacy group for GLBT elders): “AIDS advocacy forced our community out of the closet and made the cost of hiding so much higher.”

Hilary Rosen: “Senator Orrin Hatch asked me, ‘Why are you worried about this group of homosexuals?’ And I said, ‘You could be talking about me.’ I realized that I had come out to one of the most conservative senators. To his credit, he was really warm about it. That was the power of the personal connection.”

Joe Solmonese (president of the Human Rights Campaign): “The hospitals wouldn’t let us in, so we built our own. Civil-liberty organizations wouldn’t help, so we fought on our own. Politicians didn’t help, so we created our own political organizations.”

Michael Manganiello: “The first time I started to feel hope was when I joined Act Up. It didn’t matter how big the protests were—50 people or 500. Act Up was really loud and made a difference in getting access to drugs and more response from government. Storming the FDA generated a lot of media exposure, and we started to see big changes in the drug-approval process. After we demonstrated at NIH, they started to ask harder for research funding.”

“The Crisis Isn’t Over”

Because of the success of the cocktail, many began to think of AIDS as a treatable disease and stopped being as vigilant about safe practices. But patients are suffering with AIDS-related illnesses as they age, often caused by treatments that damage the kidneys, liver, and heart as well as bring about neuropathy, a degeneration of the nervous system.

John Berry: “The reason I am still negative is because of [my partner] Tom. There were times when I thought I should just get this to get it over with, so we can better understand each other. Or I thought I was going to catch it anyway. Tom was very clear: ‘You are not getting this.’ We need to teach a new generation that you can have a full relationship without jeopardizing your health.”

Wesley Combs (business leader and LGBT advocate): “It blows my mind that there are young people who think they are immune to the possibility of getting it or it’s easily manageable. They don’t have a sense of what we lost as a community and culture.”

Craig Shniderman (executive director of Food & Friends, a meal service for people with HIV/AIDS and other life-threatening illnesses): “When I started helping provide food for people with AIDS, typically they’d live weeks or months. Now they are living years. But not all of them are living well.”

Joel Gallant (professor of medicine and epidemiology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine): “I hear, ‘Doc, no one wears condoms anymore.’ Part of this is being a victim of success. It’s the impact of making it a manageable disease. But when you get HIV, you get more than just HIV. You get a propensity toward anal cancer, lymphoma, and heart disease. It’s less about fighting the complications and more about fighting the long-term consequences that accelerate the aging process.”

Septime Webre: “I think of the genius drain. The loss. What could have been if these people had lived. The Washington Ballet’s success in the ’70s and ’80s was largely a tribute to Choo San Goh, [who was with the ballet] from ’76 to ’87. He was a real ‘it boy’ of ballet. He died in 1987 [at age 39]. I can only imagine if he’d had 20 more years of choreographing, just like if we’d had 20 more years of Alvin Ailey. We’re still feeling it because of their absence—and all the works that were not made. It’s like a lost generation.”

“DC Stands for Developing Country”

While the AIDS epidemic is more under control in the United States than it once was, the threat is by no means gone.

DC health officials reported in March 2009 that at least 3 percent of DC residents have HIV/AIDS. A 2010 study reported that 17 percent of DC residents with AIDS contracted HIV through injection-drug use and 27 percent were infected through heterosexual sex.

The 2009 report noted that the more than 15,000 total HIV/AIDS cases in DC far exceeds the threshold of 1 percent that defines a “generalized and severe” epidemic. According to the 2009 DC study, black men in the District have a 7-percent infection rate.

Wesley Combs: “Congress has always hindered what DC’s Department of Health can do with prevention and care of AIDS. They prevented DC from funding needle exchange despite research that showed that needle exchange was clearly effective at reducing infection rates. For anything deemed too controversial, Congress inserts itself.”

Susan Koch (director of The Other City, a 2010 documentary about HIV/AIDS in Washington): “When we show our film, people just can’t believe this kind of epidemic is taking place in the capital of the most powerful country in the world. People are shocked. My reaction to the 3-percent figure? I was surprised it wasn’t higher based on where I was going in DC and what I was filming. It confirmed what a lot of us knew.”

Mary Beth Levin (former director of programs and services for PreventionWorks!, DC’s largest needle-exchange program, which closed in February 2011): “When people think of injection-drug users, they imagine Keith Richards after a rough night. Last year at a World AIDS Day planning meeting in [DC congressional delegate] Eleanor Holmes Norton’s office, an amfAR intern in her mid-twenties spoke up and said, ‘We can’t give up on injection-drug users in DC. Needle-exchange programs work. These people can become doctors and lawyers.’ The room scoffed at her, and then she said, ‘Hey, I am an example of it. Needle exchange saved my life. I’m starting medical school this fall.’

“Thirteen percent of injection-drug users in DC have HIV. Nationally, it’s 6 percent. State and local governments have been able to support programs like needle exchange. But DC doesn’t have a state government, and as a city DC wasn’t allowed by Congress to support needle exchange until 2007. We say that DC stands for ‘developing country’ because our health indicators are so poor.”

Ron Simmons: “We have got our own people dying in our own city, and we’re ignoring them. We’d much rather say, ‘I’m helping some poor woman in Southern Africa who got infected by her husband.’ ”

Patricia Nalls: “It’s still extremely difficult to get HIV-positive women the care we need. We have better medicines and doctors, but until we address issues of poverty, housing, and family, we won’t be able to help women effectively. I’d like more support for women like Grace, a 25-year-old immigrant who is pregnant and HIV-positive as well as married and a victim of domestic violence. She’s afraid to go to a shelter because she’s pregnant and has language barriers, so she’s living from friend to friend.”

Ron Simmons: “I answered the Us Helping Us telephone and a man blurted out, ‘I’m not gay,’ before asking me if a sexual encounter with another man he met at a nightclub put him at risk. There are lots of complicated reasons why men don’t self-identify as gay or bisexual. The trick is to allow them to get HIV information without stigmatizing them.”

Joel Gallant: “The next international AIDS conference will be in Washington in 2012. It’s the first time it’s come back to the US in years. It says a lot that it’s being held in a city with statistics that are like sub-Saharan Africa.”

This article appears in the July 2011 issue of The Washingtonian.