The opening of DC’s International Spy Museum in 2002 brought some of the trade’s secrets into the open—but the spies still own the best stories.

Up an unmarked elevator bank in Crystal City and behind several locked doors lies the Office of the National Counterintelligence Executive’s private spy display.

Filled with photos of devices like hollow nickels, clandestine cameras, and maps of dead drops and peppered with spy-themed ads and movie posters from the 1940s, the exhibit underscores the importance of espionage work.

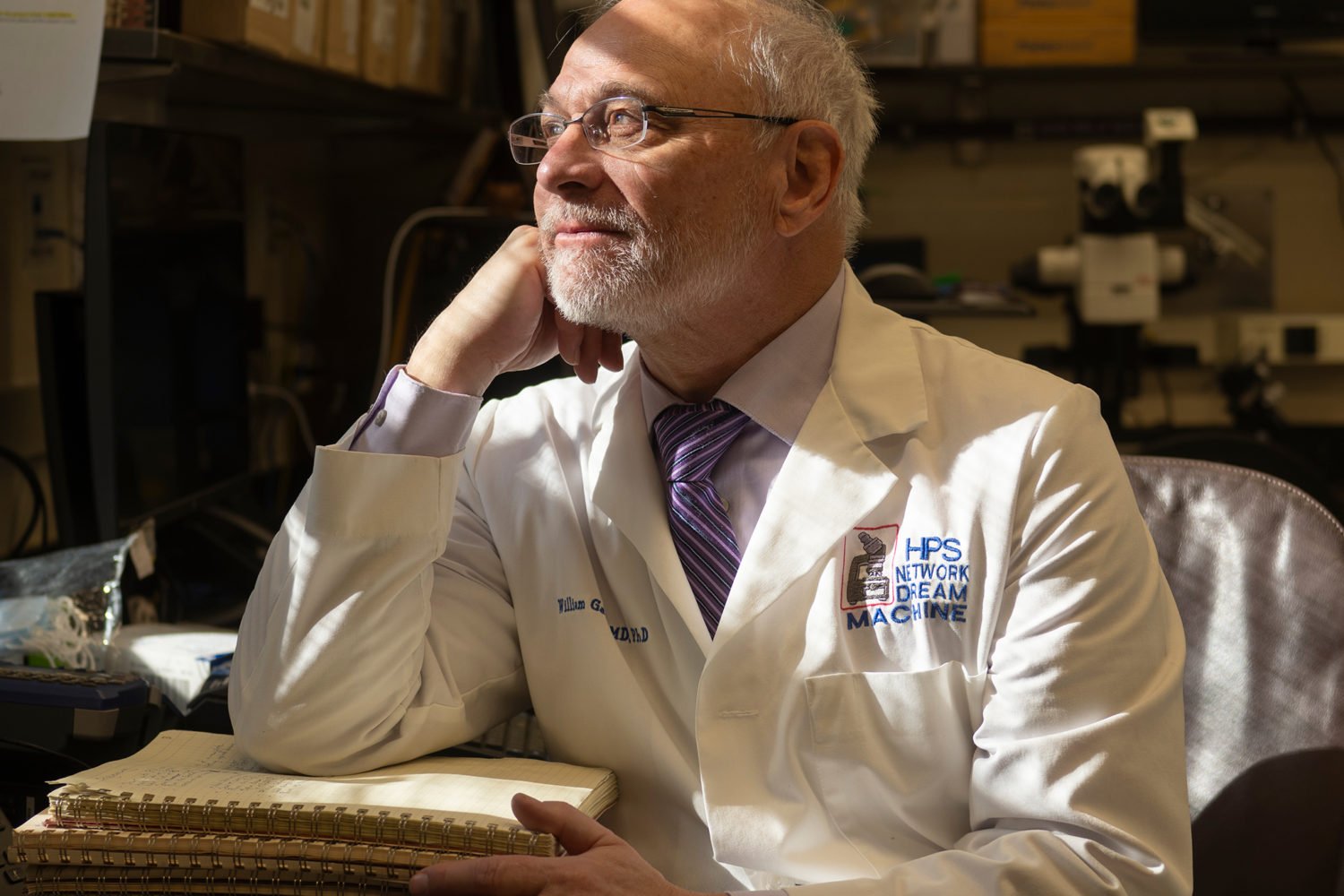

“We wanted to give people a sense of how much damage had been done by traitors in this country,” says Brian Kelley, a longtime CIA officer who organized the exhibit with help from a private collector, H. Keith Melton.

The space is dominated by photos of spies from the atomic-bomb era and a “wall of shame” of those caught during and since the Cold War—from FBI agent Robert Hanssen and the spies made famous in The Falcon and the Snowman to the wall’s most recent entry: retired Air Force sergeant Brian Regan, arrested in 2001 after trying to sell information to Saddam Hussein.

There’s even a congressman on the wall of spies: Archival research in the former Soviet Union turned up evidence that Samuel Dickstein, who represented New York state for 11 terms, volunteered to work for the Soviets in 1937 and financed his reelection campaign with money from the forerunner to the KGB.

At the end of the wall of shame is a framed question mark—representing, Kelley says, the spies who still lurk in government and those who were never caught.

“There are others out there thinking they can beat the system,” he says. “At the end of the day, we’re going to get you.”