On the morning of October 30, 2003, Devin Fowlkes couldn’t

decide what to wear. The high-school junior had a big day

ahead: the homecoming dance at noon, then a pep rally, where he’d be

introduced as starting tailback for the Anacostia High football team. He

put on jeans and a white T-shirt and went into his mother’s

room.

“Ma,” he said, “you like this?”

“Not really,” she told him.

He trusted his mom, Marita Michael, when it came to fashion.

She was the one who’d picked out his tuxedo for the prom and made sure the

color of his shirt matched his date’s dress.

“What about this?” he asked. He’d changed into a red-and-black

shirt that looked good with his new Air Jordans. Homecoming at Anacostia

was a casual affair.

That’s better, Marita said.

He took a shower, made himself an egg sandwich, and grabbed his

books.

“See you later,” his mom said. She knew he wouldn’t be home

till early evening, after football practice. “Love you.”

“Love you, too.”

About two miles away, a baby-faced Anacostia ninth-grader named

Erik Postell slept late and got a ride to school from his older brother.

He’d spent the previous night, his 15th birthday, hanging around outside

with friends in Butler Gardens, an apartment complex in Southeast. Erik

liked being with older boys, doing things he wasn’t old enough to do. He

hustled dime bags of weed and drove his own ’88 Cadillac Fleetwood, even

though he didn’t have a license.

Erik’s days revolved around girls and clothes, and he had plans

to try out for the junior-varsity basketball team. But on the day of the

dance he had other things on his mind. A fistfight in the school cafeteria

a few weeks earlier had turned into something serious, so he’d bought a

gun and stashed it in the bushes near school.

Nine years later, what Erik remembers about that October day is

that he didn’t see Devin standing there in the parking lot when he started

shooting. All he saw were the guys who’d been hassling him. He was aiming

for them.

“I can visualize it. I remember everything I had on,” he says.

“But I can’t put together my thoughts, my whole thinking process at the

time.”

The “Devin situation,” as Erik calls it, had started weeks

earlier, over a girl. A friend of Erik’s had a girlfriend, and someone was

flirting with her.

“That dude’s fakin’,” Erik’s friend said.

When someone’s “fakin’,” that means he’s taunting you, messing

with you, trying to act tough. Erik barely knew this guy, but in high

school you take on your friends’ battles.

He and his buddy walked up a school stairwell and found the guy

who’d been flirting, waiting with his friends. The two groups beat up on

each other in the cafeteria, then scattered. The security guards and the

principal rounded them up and had a mediation, Erik says.

He thought it was over, but a week later he was riding in a

friend’s car when he saw one of the guys from the cafeteria fight running

behind the car waving a gun.

Erik says his own car was shot at a few days after that, blocks

from school. The back window shattered, and a bullet hit the trunk. He was

in it at the time but wasn’t hurt.

Erik talked to a security guard at school but never called the

police. He didn’t see the point. Even if he snitched, these guys had

friends, and their friends had friends.

“I weighed my options,” he says. “I could continue to go to

school and hope it might end, or I could deal with it

head-on.”

After the homecoming dance and pep rally, around 3 o’clock,

Erik says he and a friend were walking home and saw the white Cadillac of

one of the guys he’d been arguing with coming toward them; two guys were

in it. They pulled up beside him. Erik had the pistol in his bag. He was

sure these guys were after him again. They made eye contact, one guy

looked at him and laughed, and Erik thought he saw one of them reach for

his pocket. He took aim as the car was pulling away, missed, and ended up

firing into a parking lot filled with kids.

Two hours later, Devin Fowlkes, a nice kid he knew from art

class, was dead.

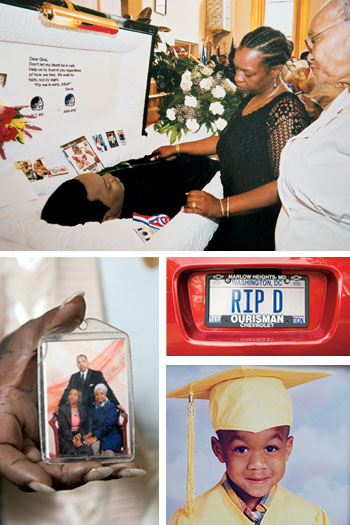

Devin was the tenth youth killed in the District in 2003 and

the 207th murder that year. Since then, another 130 juveniles have been

killed in DC, many at the hands of other teens.

Devin’s name went on a brown file folder at the Metropolitan

Police Department’s homicide branch in Southwest DC.

The case was solved quickly: At his mother’s urging, Erik

Postell turned himself in a day later and confessed. Because he was a

juvenile, his name was never released to the media.

Now 23, Erik has served his sentence and is trying to piece

together a life for himself. He’s hoping he can help keep his young

nephews out of the street life that sucked him in, a world where R.I.P.

shirts—with a dead person’s face on them—are in style.

Erik arrives for an interview on an early-spring evening

wearing dark-blue jeans, a sweater with buttons, and a crisp green Oakland

A’s baseball cap. He chooses his hats based on style, not teams. He’s

always nicely dressed for interviews, always articulate, always

introspective. If a killer has a look or a tone, it’s not

Erik’s.

He isn’t used to talking about Devin. He’s told a few of the

friends he’s met in recent years, but only if he thinks they’ll be in his

life awhile. It’s part of who he is, he says, and he can’t pretend it

isn’t. But it’s not like he robbed a house. He killed somebody—that’s not

something you go around sharing.

Erik doesn’t have flashbacks or see Devin in his dreams—perhaps

because he never saw Devin get hit, never saw him lying unconscious in the

school parking lot. He has looked at photos of Devin on Facebook and felt

something. Not guilt, exactly—more like regret. He wishes he had known how

to walk away from a bad situation. But in that place at that time, he did

what he felt he had to do to protect himself.

“I made a bad decision,” he says. “People from all walks of

life make bad decisions.”

Erik chose a long time ago to move forward, not backward. He’s

hoping he can do what Devin’s mother asked of him soon after the shooting:

“Get out of jail and change your life around for me,” she said. “Then my

son can live through you.”

T o make sense of what happened, Erik says, you have to

understand his life at the time. He was living with his mother, but she

was working and going to school. For him, that meant late nights outside.

No rules, nobody calling him in for dinner. He was running the streets at

age 14, so when he ran into trouble at school, a gun was the easy

answer.

Erik’s grandmother, Marva Green, had cared for him from the

time he was two because his mother, Michele, was an addict and his father

wasn’t around. Erik adored his mother.

“Take me with you, Mommy,” he’d say when he saw her fixing her

hair to go out. Green didn’t want her daughter dragging Erik and his

brother, Daryl, into her self-destructive lifestyle, so she helped get

Michele into rehab and said she would take the boys. For a while,

everything was fine. Erik’s grandma filled his lunch box with homemade

fried chicken and cookies, and he talked about becoming a doctor when he

got older. In elementary school, he would come home, do his homework, and

run around with the neighborhood kids until dark. He had his own bedroom,

but in the morning Green often would find him curled up at the foot of her

bed.

When Erik was 11, he and a friend wrote their names in graffiti

on the exterior of their middle school. Erik’s grandmother couldn’t help

but laugh. “Why would he write his name?” she thought. Her

grandson started hanging around older boys she didn’t know and telling her

she was too strict. Michele was sober by then, so Green told Erik it was

time to go live with his mother.

His mom had an apartment on 25th Street, Southeast, a few

blocks from his grandmother’s house. She was working too much to keep tabs

on him. He’d always liked brand-name clothes, even as a little boy, and

the guys he knew who were dealing drugs seemed to have the best of

everything.

Erik made a good profit on the corner because he never smoked

what he sold. As a boy, he’d spent weekends with his mother at the Oxford

House—an addiction-recovery group home in a nice neighborhood in

Northwest—and sat with her in Narcotics Anonymous meetings, where he saw

men without teeth and heard people with AIDS talk about sharing

needles.

“People really don’t understand how much a kid can comprehend

at a young age—a five- or six-year-old can soak in so much from just

listening,” he says.

He made so much money dealing that he might go to bed at night

with $600 in his pockets. A few hundred for a gun was no big

deal.

B en Clark (not his real name), a community activist who does

youth-violence work in the District, has met lots of kids like Erik. Most

buy guns because they’re afraid, he says: “Eight times out of ten, when

you try to kill somebody, it’s because you fear that if you don’t kill

them, they’ll kill you.”

He once tried to shake hands with a middle-schooler he passed

on the street, and the boy wouldn’t take his hands out of his sweatshirt

pocket because he was trying to conceal a machine gun.

“What the hell are you doing?” Clark asked him.

“Man, they coming through my neighborhood,” the boy said. “I’m

gonna do that to them.”

Do that meant kill them.

“No, you’re not,” Clark said. “Give me some time to talk to

you.”

Two decades ago, when Clark was growing up in DC, he says, you

could look at certain guys and know they were dangerous. The thugs stood

out. Now everybody blends together and you never know who might be

carrying a weapon.

“Years ago, there were rules to this,” Clark says. “Somebody’s

with their mother, you wouldn’t shoot them. If somebody’s in their house,

you wouldn’t go shoot up the house. Nowadays, they don’t care about the

rules. The rules are ‘I live—you die.’ ”

People call Clark, who has served time for attempted murder,

when something bad is about to happen. His job at the nonprofit he works

for is to step in and try to quash beefs before they become violent. It’s

not the type of work you want to bring attention to, Clark says. If your

name is out there, the kids will stop trusting you: “You’re not supposed

to hear about the truces.”

He’s especially busy after a shooting, when there’s word on the

streets that someone is going to retaliate. Many fights start at school

and spill over into the community. The key, Clark says, is to get to the

kids before they get to each other.

“Somehow, God has blessed me to be able to de-escalate. I can

talk to kids and they’ll listen,” he says. “I’ve been in instances where I

didn’t even know a guy, and I ran and pushed another kid out of the way so

he didn’t get shot, and the guy pointed his gun at me. The other kids were

like, ‘Nah, that’s Ben,’ and he put the gun down.”

He recently got involved with a feud between a neighborhood

crew and a group of high-school football players.

“Someone called me and said, ‘Man, we need you to come over and

deal with this before it gets into gunplay,’ ” Clark says. “We negotiated,

and I had to settle for someone getting beat up.”

A colleague of Clark’s once received a call from a member of

DC’s Trinidad crew. “The E Street dudes are in our neighborhood right

now,” the guy said. “We’re about to do that.”

“No, no—hold on!” he said. He made a couple of calls and found

out the E Street guys were in Trinidad checking out girls—they weren’t

looking for trouble. Nobody got hurt. “A lot of times we’re able to stop

these things,” Clark says. “Sometimes we find out too late.”

When Erik fired his pistol, Devin Fowlkes and his teammates

were hanging around in the parking lot, waiting for football

practice.

Willie Stewart, who had coached the Anacostia High Indians for

more than two decades, was finishing some work in his keyboarding

classroom when he heard two loud pops. He thought someone was messing

around with firecrackers. Then one of his players banged on his classroom

door.

“Devin got shot!” the boy said.

Stewart ran outside and saw Devin lying on his back, eyes

closed, bleeding through the football jersey he’d worn to the pep

rally.

“Who’s riding with him?” a paramedic asked.

A father of three sons, Stewart got into the ambulance and

prayed. He’d already lost other players to gun violence: Anthony Butler,

Rodney Smith, Lashon Preston, Donald Campbell. Preston was killed on his

front steps the night before a game; Campbell was hit twice over a small

bag of marijuana.

You don’t have to settle your problems with guns, he

would tell his team. A gun is so final.

Stewart’s players had told him how easy it was to get a gun—a

“burner,” they called it. You could rent, buy, or borrow one. It’s not

that it was cool to carry one, they said; sometimes you just had to. When

someone disrespected you—on the basketball court, in the hallway at

school—you had to straighten it.

“What are you gonna do about that?” he would hear students say.

“You gonna take that?”

Devin, a junior, wasn’t one of the players Stewart worried

about. He had a B average. His mother, Marita, came to all of his football

games and rang a cowbell in the bleachers. After practice, he would go

home and play video games with friends. He’d call Marita at the Verizon

Center, where she was a cook, ask her to bring him a half-smoke or a

hoagie, then meet her at the bus stop to walk her home. He was a good kid,

polite, the kind who helped elderly neighbors take in their

groceries.

But in Anacostia, good kids still caught bullets in the chest.

“You need to work your butt off, get a scholarship, and get out of here,”

Stewart would tell his players. “Get out of DC.”

A year earlier, when snipers were terrorizing the area, DC

public schools had canceled some high-school football games to keep teams

out of harm’s way. Stewart couldn’t understand why. A reporter asked him

if his players were afraid of the snipers.

“Afraid?” Stewart said. “These kids see guys shot in their

neighborhoods or find dead bodies in cars. They live it every

day.”

Devin, now unconscious, was in his third season playing for

Coach Stewart. Though he was small, he’d convinced himself he could play

college ball. He had pictures of NFL running backs in his locker and liked

to tell his mom that one day he was going to buy her a new

house.

Erik’s mother, Michele, was at work at the State Department

when she saw the news on television about a shooting outside her son’s

school. She couldn’t reach Erik on his cell phone, so she left work to

look for him. She wanted to make sure he hadn’t been hurt.

For a few hours after the shooting, Erik says, he didn’t

realize he had hit anybody. He’d fired and run. He never saw one of his

bullets pierce Devin’s chest and another graze a young girl’s arm. He’d

gone back to Butler Gardens as if nothing were wrong.

“One of my friends told me, ‘Somebody got shot down at the

school,’ but it didn’t really sink in,” Erik says.

His mother reached him later that evening. By then, friends

were telling Michele that her son may have killed somebody.

“Where are you?” she asked Erik. She was terrified. Homicide

detectives had kicked in her front door. She didn’t want her son’s picture

on television.

“I’m okay,” he said. “I’m around.”

She had missed a lot of Erik’s life while she was in rehab, but

she was back on track, working and going to Strayer University at night.

She couldn’t always control her son—he stayed out past curfew and got in

trouble for stealing cars—but she checked his coat pockets and dresser

drawers.

This was the kind of thing she had always feared, the reason

she watched the clock waiting for Erik to come home and why she checked

his room in the middle of the night to make sure he was there. She had no

idea her son had a gun, but she knew they lived in a place where some

teenagers went out and never came back.

“We’re going to the police station,” Michele told Erik. “You

need to turn your-self in.”

Former police captain Michael Farish, who headed DC’s homicide

branch until his retirement earlier this year, got tired of hearing young

people make excuses for killing one another.

I thought he might shoot me.

I thought his crew was gunning for my crew, so we strapped

up first.

“When I was younger, kids got in fistfights,” he says. “We’ve

lost something somewhere along the way.”

Farish doesn’t buy the idea that a teenager like Erik could

shoot someone and not realize what he was doing.

“They know what the consequences are—they’ve seen it. Because

I’ve seen them, at 10, 11, 12 years old, standing out on the

front stoop watching the police roll over the dead body,” he says. “They

heard the gunshots, maybe even saw the shooting. They know

dead.”

Farish has never forgotten the young guys who shot a kid with a

9-millimeter, a .45, and a shotgun while he was waiting at a traffic light

in Southeast because they didn’t like the way he’d looked at them outside

a barbershop. But most of the teens he deals with are decent kids who

weren’t raised to value human life, often boys who grew up without fathers

and turned to the streets to get attention.

Farish remembers a 17-year-old who robbed a dry cleaner’s shop

and killed a Korean woman who worked there. An older lieutenant

interrogated the teen while Farish watched from another room. The

lieutenant spoke calmly and respectfully, as if talking to his own son,

and asked the boy why he’d shot the woman.

The young man started to cry. “I’ll tell you everything,” he

said. When the officer stood up, the kid jumped out of his chair. Farish

thought he was going to attack the lieutenant, but he put his arms out and

hugged him. “No man has ever spoken to me like that,” he said.

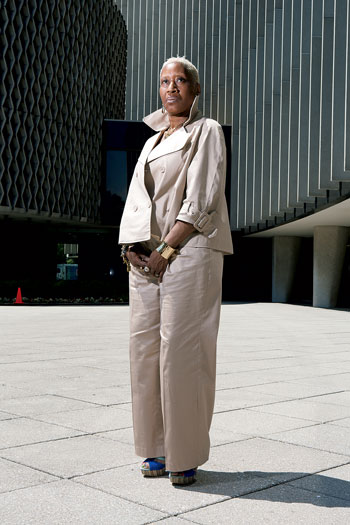

Devin’s mother, Marita, wanted to be the one to close her son’s

casket. She didn’t want someone from the funeral home doing

it.

“Go sit down,” she told Devin’s grandmother. Thousands had

gathered for the service, including DC mayor Anthony Williams and police

chief Charles Ramsey. “I need to do this by myself.”

Marita was used to hearing from her son two or three times a

day. A friend had told her once that she’d never seen a teenager call his

mother as often as Devin did.

“What you doing?” he would ask on the phone.

“Same thing I was doing two hours ago,” Marita would say. “Boy,

why don’t you go have fun?”

She always knew where he was. The one time he tried to sneak

out, she got out of bed, walked to the party she knew he had gone to, and

banged on the door.

“Dang, Ma,” Devin said. “How’d you find me?”

She was there for her son’s last breaths at Howard University

Hospital, and she was going to be the last person to lay eyes on him. Some

people got shot ten times and survived; her son had taken one bullet and

died. She told herself God had better plans for him.

She got angry when she heard someone say Devin was in the wrong

place at the wrong time. He was at school, she

thought.

Friends of Devin’s had told Marita what happened in the parking

lot that day. She knew that the young man who shot her son wasn’t aiming

for him and that he had turned himself in. She also knew that one of

Devin’s best friends was serving time at the Oak Hill Youth Center, where

Erik was being held. The facility, since closed, had a reputation for

violence.

That boy is not safe there, she thought. Someone is going to

kill him for what he did to Devin.

Marita called Reverend Anthony Motley, a family friend who

volunteered at Oak Hill, and asked him to get Erik into isolation. She

didn’t want Erik’s mother to go through what she’d been through. One dead

child was enough.

A t the Oak Hill Youth Center, Erik stood on his bed to talk to

other inmates through the vents. Being in isolation meant about 20 hours a

day in his room.

For a while, Erik believed that the bullet that hit Devin,

ricocheting inside his chest and tearing through his aorta, came from

someone else’s gun. He was sure the guys he’d fired at had shot back. He

thought he’d heard their gunshots.

“They were saying I killed somebody,” he says. “I didn’t want

to accept that.”

He had spent three months in a juvenile facility in Baltimore

when he was 13 after he and some friends filled a minivan with stolen dirt

bikes. But the place in Baltimore seemed like summer camp compared with

Oak Hill. Now 15, he was small for his age. The kids here knew what he was

accused of doing and taunted him during bus trips to court. When his

mother came to visit, she noticed bald spots on his head. His hair was

falling out.

He hadn’t been at Oak Hill long when Reverend Motley came to

see him. Motley, who had known Devin since he was seven, practiced

redemption ministry, which meant everybody got second and third chances.

He had suggested to Marita that she reconcile with Erik and his family, an

idea she didn’t resist.

An officer led Erik into a room where Reverend Motley was

waiting.

You’re just a kid, Motley thought. How could you do something

like this?

“Devin was like my grandson,” he told Erik. “Now I have to come

and face his killer. How do you think that makes me feel?”

Motley talked to Erik about accepting God into his life. Erik

didn’t say much—he listened—and Motley saw tears in his eyes.

T here was a point during Erik’s trial in March 2004, five

months after the shooting, when the gravity of what he was accused of hit

him. He was on trial for first-degree murder.

“His mother was on one side, my mother was on the other side,

but he was nowhere around,” Erik says. “I had to come outside of myself

and realize: Her son is no longer here.”

In court, where Erik was tried as a juvenile, his mother and

grandmother sat behind him every day. Michele would go to work in the

morning and leave early for the trial, hoping coworkers wouldn’t figure

out where she was going. She stopped answering her phone and hid from

television reporters.

“Just leave me alone,” she’d tell them. “Somebody’s child has

died.”

She exchanged looks with Devin’s mother in the courtroom, but

the two didn’t speak. Marita was angry, but not at Michele.

It’s not her fault, she’d think. She didn’t shoot my

son.

She was mad at whoever had handed Erik the gun, a person whose

identity she’d never know.

“Every child out here that gets killed with a gun—killed by

another child—some adult is responsible for that,” she says. “Whether they

sold it to him, gave it to him, or told him to hold it. Why would you give

a 14-year-old child a gun?”

Marita moved from her home because she couldn’t bear to see

Devin’s bedroom, where friends had left messages on the walls and ceiling.

She became an advisory neighborhood commissioner and helped reopen a

recreation center that had been closed for a decade.

“There’s nothing for kids to do,” she says. She’d relied on

places like that when she was a child. She saw violence in her Southwest

DC neighborhood—a friend was killed in an alley after playing cards at her

house in junior high—but she always had somewhere to go after

school.

“I was in the rec center till it closed at 8, then we was in

the house stimulating our minds,” she says. “Kids don’t do that no

more.”

Erik turned on his Discman and listened to Kanye West and Jay-Z

on the flight to Georgia in June 2004. It was his first time on an

airplane.

His fears were different than they’d been at Oak Hill, where he

had made straight A’s in classes. He was going somewhere unfamiliar, far

from his mother and grandmother, and he wouldn’t be going home for a very

long time.

A judge had convicted him of second-degree murder and committed

him to the Department of Youth Rehabilitation Services until age 21. At

sentencing, the judge told Erik that he needed to start taking

responsibility for firing at a car with two human beings inside, aiming to

kill them, and that it was time to accept that the bullet that hit Devin

came from his gun. Ballistics evidence had proven it.

“It is particularly horrible and tragic that someone not

involved in the beefing, who was by all accounts an outstanding young man,

is now dead,” she said in court. “You have a good mind. You have the

support of your family. You are alive, in a city where all too many young

people are not. And maybe you will be able to put that together in some

positive way.”

The residential treatment center, a gated community outside

Atlanta, looked like a plantation to him. He was used to rowhouses in

Southeast; he’d never seen a house with pillars out front and a circular

driveway. The guys in his dorm looked at him as if they were trying to

figure him out. Other kids from DC were there, but he believes he was the

only one who had killed somebody.

For the first few weeks, Erik kept to himself. Classes were

easy for him—some of his peers couldn’t read—and teachers let him take

lessons back to his room. He liked art class and English. After school,

he’d play basketball or go swimming, then meet for Life Skills classes

about how to cook or how to manage his anger.

A counselor named Natacha started bringing books so Erik could

read about people who’d made mistakes and changed their lives. He rarely

talked about the shooting, and sometimes she would forget what he had

done. He asked her once why he had to grow up so soon.

In 2005, when Erik was 16, he moved to an independent-living

program in Georgia as part of his sentence. He went to a public high

school, where he played basketball and football and ran track. Friends

invited him over for dinner, and for the first time in his life he saw

mothers and fathers living in the same house. A friend’s mother altered

his suit for the senior prom. He studied for his learner’s permit and went

on dates. A counselor took him to poetry readings at Morehouse

College.

I want this kind of life, he thought.

Erik once heard a staff member at his program in Georgia say,

“The only thing you should be able to do is work. You’re a

murderer.”

Devin’s mother, Marita, has never thought of Erik that way. She

believes he’s a good kid who had something missing in his life and went

down the wrong path.

“He turned himself in,” she says. “A lot of people would have

kept running.”

Soon after Erik was sentenced, around Mother’s Day 2004,

Reverend Motley invited both Marita and Michele to a dinner event at

Greater Southeast Hospital called From Both Sides of the Tape. He wanted

mothers who had lost children to homicide to talk to the mothers of the

young men responsible. Both, he believes, are victims.

He invited two other moms, Pearl Boykin and Michelle

Richardson-Patterson. Boykin’s son, T.J., had shot and killed James

Richardson inside Ballou Senior High School three months after Devin’s

death. Erik’s mother, Michele, didn’t show up. She told Motley she wasn’t

ready.

A few weeks later, Marita saw Michele at one of Erik’s review

hearings. The judge checked in with Erik by phone every few months to see

if he was staying on track in Atlanta; Michele and Marita would sit in the

courtroom listening. After one of the hearings, both of them stood up and

walked toward the door. Then they stopped.

“I’m sorry,” Michele said.

“That’s all I really wanted to hear,” Marita told

her.

Motley sent the mothers on a weekend retreat to a farm in Anne

Arundel County, and they drove in the same car.

“I grabbed her hand and said, ‘I’m gonna hold your hand all the

way—it’s gonna be all right,’ ” says Marita. “I said, ‘You lost, too. You

lost the son you thought you had.’ ”

The two women started talking often and going out to dinner.

With Motley’s guidance, they helped form a group called Forgiving Mothers

Straight From the Heart and hosted teas at the Willard Hotel for women who

had lost children. They traveled to Atlanta to speak to a group of

churchgoers about forgiveness. Michele went to candlelight vigils in

Devin’s honor.

Marita and Erik recently met for the first time. Marita—who at

age 49 is battling Stage IV throat cancer—had always planned to meet him

in person. They’d spoken by phone more than once, and Erik had told her

how sorry he was.

“It was nice,” she says of meeting Erik. “We just had a regular

conversation. I could see the difference in him, the maturity. He’d

grown.” Erik says he didn’t feel prepared to meet her, but he went with

the hope that it might be a step toward closure. For both of

them.

Erik received his high-school diploma in Georgia and was sent

back to DC in 2007 to continue his sentence in a group home in Northwest.

When he returned, he had a reputation—a “tag,” he calls it. On the street,

being convicted of murder wasn’t such a bad thing. People wanted to be his

friend.

He got a job with a moving company but hated it. He’d get off

work, hang out in his old neighborhood, and take the Metro back to his

group home by curfew.

He’d been away from home for four years and felt proud of what

he’d accomplished—good grades, a diploma, friends. But the streets hadn’t

changed, and as an adult he was expected to fend for himself.

He stopped by his grandmother’s house one night for dinner and

told her he couldn’t stay long.

“Why are you rushing?” she asked.

Later that evening, a neighbor knocked on her door to tell her

Erik had been arrested a few blocks away. Marva Green was furious. She had

asked Michele to move to Atlanta so Erik didn’t have to come back to

Anacostia, but her daughter had a stable job and didn’t want to

uproot.

You’ve been given a second chance, Green had told her grandson.

Don’t mess this up.

Erik pleaded guilty to possession of heroin with intent to

distribute and was sentenced to two years in prison.

He was angry at himself. “From that point on it was like,

‘Okay, enough mistakes,’ ” he says.

He read philosophy books and suspense novels in jail. He took

real-estate courses and studied Islam. He starting writing. He got to know

guys who’d been locked up 20 or 30 years, some of whom were never going

home.

I’m still young, he told himself.

He served 20 months, then in 2010 entered a job-training

program called Project Empowerment. He was assigned a contract job as a

legal assistant in the Office of Administrative Hearings in Judiciary

Square, a few blocks from the courtroom where he’d been convicted of

killing Devin. He wore a tie to work every day.

There was a moment last year when Erik found himself wondering

what Devin would be doing now if he were alive. A trip inside the court

building had him thinking.

“I’d never thought about all the time that’s gone by, all the

stuff Devin might have accomplished between then and now,” he

says.

He doesn’t allow himself to get stuck on thoughts like that. He

rarely even says Devin’s name. He prefers to focus on the message, on what

he’d say if he were standing in front of a group of kids living the life

he lived nine years ago.

“You have to think about the effect your actions can have, the

magnitude of what could happen,” he says. “You could take somebody’s life

and you could lose yours in the process. Are you willing to sacrifice all

of that over a situation that tomorrow you might not even care

about?”

Sometimes he wonders where he would be if the shooting hadn’t

happened. He recognizes the twisted reality: If he hadn’t fired his gun

after the homecoming pep rally and been sent away for treatment, he might

never have left Southeast.

“I don’t think I would have graduated high school,” he

says.

He might have been murdered. He might have shot somebody when

he was 18 instead of 15 and ended up serving life in prison. One of the

guys he was shooting at that day is dead, he says. Another drives a

Metrobus.

“There’s nothing I can do to change what happened,” he says. “A

mother lost her son, and lives were changed forever. I just try to live

through it and past it. If I can become a better person, then I’ll feel

like I accomplished something.”

Erik says he’s learned how to walk away from trouble. He can

visit his grandmother in Southeast and ignore the temptations of the

streets. Yet he’s still finding his way.

At 23, he’s living with his girlfriend in Oxon Hill, finishing

a novel he started writing in jail, and working part-time for a friend at

a used-car lot. Since prison, he’s dabbled in photography and club

promotions.

One of his goals is to own a chain of luxury hotels by age 45,

though he’s not sure how to make that happen. He enrolled in business

classes at Prince George’s Community College last fall but decided to take

a break because he couldn’t get motivated. “I’m scared of failure,” he

says.

Sometimes he thinks he wants to be a youth counselor, but he

worries about that kind of responsibility—worries about having kids look

up to him, the influence he could have on their lives.

He’s lost, in a way, though he wouldn’t say that. He says you

don’t “find” yourself; you create yourself, and that’s what he’s doing

now. He’s creating the person he wants to become, a person who would make

Devin’s mother proud. He hasn’t forgotten what she asked of him years ago.

Get out of jail and change your life around for me. That way my son

can live through you.

“I’m giving myself till my 25th birthday to find out what I

really want to do,” Erik says. “I just hope my good outweighs my

bad.”

This article appears in the July 2012 issue of The Washingtonian.