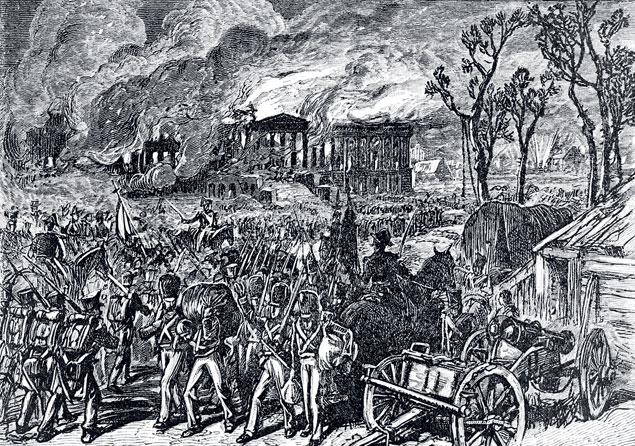

Not long after sundown, as night fell on the streets of the

nearly abandoned city, the sky above Washington flared suddenly alight

again. It looked at first like flashes of sheet lightning breaking the

muggy August air. But then an orange glow settled over Capitol Hill,

shining brighter and brighter, a beacon of catastrophe.

From Maryland hilltops, eastward across the Anacostia River and

northward on the heights of Tenleytown, soldiers and officers of the

American army looked on in stunned silence, watching flames rise above the

halls of Congress. President James Madison and members of his Cabinet,

fleeing on horseback deep into Virginia, kept stopping to gape at the

conflagration each time it became newly visible at a rise or a bend in the

road, unable to turn their backs fully on the disaster they were leaving

behind. At a house on the far bank of the Potomac, the First Lady kept a

silent vigil, hour after long hour. Many thousands of ordinary citizens

watched as well. In an era before electric lights, the fire on the horizon

could be seen from 40 miles away.

At the Capitol building, the enemy had been brutal in its

efficiency, well trained as it was in the art of war. Initially the

edifice, as if possessed of its own stubborn will to survive, had resisted

the onslaught, its thick pinewood roof failing to ignite as Congreve

rockets—weapons only recently developed—were fired at it from below. But

red-coated soldiers tore the spectators’ gallery from the walls of the

House chamber and hacked fine woodwork into kindling with their hatchets,

tossing mahogany desks, chairs, and tables atop the wreckage to form an

enormous pyre at the center of the room. They smeared gunpowder paste on

the walls before firing more rockets, this time directly into the heaped

debris.

Now the flames roared to life, caught, and spread. Tendrils of

fire climbed the heavy silk curtains lining the hall and consumed the

crimson canopy above the speaker’s chair. As the pyre became an immense

bonfire, chandeliers crashed from the ceiling and plate-glass skylights

shattered and melted.

Eerie figures of animals and humans seemed to circle the

inferno like dancers in a nightmare: the immense sandstone eagle beneath

the ceiling; the godlike allegorical figures of Agriculture, Art, Science,

and Commerce; the marble statue of Liberty clutching a scrolled

Constitution, her foot treading on the fallen crown of despotism. Then the

sculpted stonework began cracking under the intense heat. Faces and wings

blackened and fell away; goddess, crown, and Constitution powdered into

lime.

Elsewhere in the building, invaders continued their relentless

obliteration, smashing furniture in the Supreme Court chamber—at the time

housed inside the Capitol—before setting it, too, ablaze. No such efforts

were required to destroy the Senate, where the wind drove in the flames to

consume the elegant hall. Upstairs in the Library of Congress, thousands

of handsome, leather-bound volumes, fine colored engravings, and rare

maps—many selected personally by former President Thomas Jefferson—were

reduced to ashes.

At the height of the blaze, the ravaged roof beams finally gave

way and the ceiling of the House chamber collapsed with a thunderous

whoosh, sending a geyser of sparks into the night sky. To distant

observers, it must have seemed as if Capitol Hill had erupted like a

volcano. Downwind, neighboring houses began to catch fire.

For Washingtonians that day—August 24, 1814, two years into the

War of 1812—the devastation of their city was a blow that went beyond the

physical loss. In retrospect, and by the standards of more recent urban

disasters, this one might seem mild: In the final reckoning, no American

lives were lost and little private property was destroyed. Washington’s

population at the time was just 10,000 or so, fewer than half the number

of inhabitants of DC’s Cleveland Park today.

But that relatively small community had built the federal city

with its own hands. Hardly a soul within its boundaries—from

African-American slaves and Irish immigrant laborers to congressmen and

Cabinet secretaries—had not participated somehow in the effort that, in

barely 20 years, had begun transforming a landscape of tobacco fields,

pine flats, and muddy farm lanes into the capital of a rising world

power.

Foreign visitors may have mocked what Charles Dickens called

the “city of magnificent intentions,” with its Grecian edifices rising

alongside ramshackle taverns. Yet at a time when most Americans lived in

simple wooden houses and public art was almost unknown, the Capitol’s rich

adornments—the silk brocade and polished mahogany, the sculptures carved

of Virginia stone by artists from Italy—were national treasures, the

property of every citizen. In its rudimentary state, Washington was a

promissory note against future greatness.

Watching the Capitol burn, a middle-aged clerk from the Navy

Yard—old enough to remember the revolution that had won the nation its

freedom from Britain some three decades earlier—felt physically sickened

at “a sight, so repugnant to my feelings, so dishonorable; so degrading to

the American Character.”

Worst of all was that the disaster had not needed to happen. It

had occurred because of Americans’ ineptitude and cowardice in the face of

a longtime enemy and because of their leaders’ imprudence. The national

government that had seemed so solid just a week earlier had, like the

Capitol, crumbled in an instant. This, more than anything, made the

tragedy almost impossible to bear.

In the dark early hours of August 19, a hawk-nosed, sunburned

British officer peered from his longboat toward the alien shore ahead.

Rear Admiral George Cockburn was taking one of the biggest gambles of his

career. Now 42, he had faithfully served the Royal Navy since going to sea

at age 14, not long after the last American war. He had battled the

Spanish and the French in the East Indies and the Mediterranean and

learned the ploys and tactics of a fighting captain under Lord Nelson

himself.

With his brash swagger and weatherbeaten hat trimmed in gold

braid, Cockburn (pronounced “co-burn,” the admiral would thank you to

remember) was the very model of a British naval commander. Despite his

imperious manner, his subordinates worshiped him as an officer who—in the

words of one teenage midshipman—“never spared himself, either night or

day, but shared on every occasion, the same toil, danger, and privation of

the [lowliest] man under his command.”

Yet Cockburn had faced considerable skepticism over the past

several months in pushing for an attack on Washington. His superior, the

vacillating Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane, chief of British naval

operations in North America, had at first favored the plan but then turned

his attention to the less risky strategy of freeing and arming

African-American slaves. Major General Robert Ross, the Army officer who

would have to command the land operations, was similarly

hesitant.

Back in Great Britain, however, civilian opinion was clamoring

for the impudent Yankees to be taught a lesson. “Now that the tyrant

Bonaparte has been consigned to infamy”—which was to say the island of

Elba—“there is no public feeling in this country stronger than that of

indignation against the Americans,” the Times of London had

editorialized a few months earlier.

Perhaps the origins of the War of 1812 were, in most Britons’

and Americans’ minds, half lost in a tangle of mutual affronts: trade

disputes, insults to sovereignty, and the multiple contusions caused by an

upstart power jostling against an established one. In any case, the

battles already fought on land and sea had afforded ample fodder for

mutual hatred. British commanders had burned villages and plantations

along America’s shoreline and allied with Indian tribes in ravaging the

frontiers. Americans had sunk British frigates and burned legislative

buildings in the Canadian provincial headquarters of York (now

Toronto).

So Cockburn had argued for the capture of the enemy capital,

“always so great a blow to the government of a country,” more for its

psychological value than its strategic importance. No more than 48 hours

after landing troops near the Maryland village of Benedict, he promised

Cochrane, he and Ross could take Washington “without difficulty or

opposition of any kind.”

Disembarking with a modest force of 4,500, he was about to put

his bravado to the test. Surely Cockburn, a veteran of the Chesapeake

campaign, could not have seriously imagined that the Yankees would

surrender the seat of their republic before firing a single shot. But hour

after hour passed without a glimpse of the foe.

The only immediate enemy was the broiling midsummer heat, which

took an awful toll on men in heavy wool uniforms hauling muskets and

ammunition and trundling artillery pieces, with legs still wobbly after

months at sea. (The Maryland climate, one Briton recalled decades later,

was “little inferior to that which I have subsequently experienced in the

Gulf of Guinea.”) To boost morale, drummers and buglers struck up a

stirring air from Handel: “See, the Conqu’ring Hero Comes!”

The British knew that one substantial military barrier did lurk

in the vicinity: an American flotilla of more than a dozen gunboats under

Commodore Joshua Barney, taking shelter somewhere up the nearby Patuxent

River. The invaders’ first mission was to destroy the small fleet—the sole

remaining US naval presence in the Chesapeake Bay—lest it become a

nuisance.

Indeed, Barney might well have offered resistance that could

have pinned down the British while Americans prepared to defend the

capital. As it was, it took three days to reach the point where the

flotilla lay anchored far upstream. But scarcely had the British force

glimpsed the vessels than they began, one by one, to explode: Barney,

obeying orders from his superiors in Washington, was destroying his own

fleet rather than letting it fall into enemy hands.

As for Yankee land power, the redcoats finally encountered

their first armed adversaries that same morning: a lone sailor who fired

unsuccessfully at one of Cockburn’s aides from behind a bush (he was

quickly captured and subdued) and a few horsemen who appeared atop a bluff

(they galloped off when the British fired in their direction).

As Cockburn and Ross were beginning to guess, the Americans had

decided to concentrate their troops farther inland, where they could face

the invaders on ground of their own choosing. The British expedition, deep

into unfamiliar enemy territory with a small, heat-exhausted force, faced

ever greater risk of being caught in a trap. Mindful of this, Cochrane

sent a courier from his flagship with instructions to terminate the

mission: In provoking the flotilla’s destruction, it had accomplished

quite enough.

Ross was ready to obey, but to his chagrin, Cockburn insisted

on ignoring the dispatch. The two commanders argued late into the night.

Finally, as August 23 dawned, an exhausted Ross capitulated: “Well, be it

so, we will proceed.” Soon their army was on the march toward the capital

city.

It took another day of slow, sweltering progress before British

troops spotted a large dust cloud hovering a couple of miles ahead.

Drawing closer, they spied the glinting bayonets and musket barrels of an

American army awaiting them, drawn up atop a hill alongside the town of

Bladensburg. One of Ross’s officers, Lieutenant George Gleig, was struck

by the contrast between the foes. All around him, immaculately uniformed

redcoats marched in perfect cadence, “silent as the grave, and orderly as

people at a funeral.”

The Yankee militiamen—though well armed and outnumbering the

invaders—scarcely looked like soldiers at all, dressed in a motley

assortment of uniform parts and civilian clothes. From the moment they

spotted the British, they began filling the air with excited shouts. These

would-be defenders, Gleig scoffed, “might have passed off very well for a

crowd of spectators, come out to view the approach of the army which was

to occupy Washington.”

At first, these “spectators” put up a surprisingly stiff

resistance, loosing volleys of gunfire that cut down redcoats by the

dozens. One bullet severed the strap of Cockburn’s stirrup, and another

killed the marine who stepped in to repair the damaged leather. But then

shouts of “Forward!” sounded up and down the British line, and as the

veteran soldiers marched ahead in lockstep, the Yankee militiamen began to

break and run.

“Never did men with arms in their hands make better use of

their legs,” Gleig wrote. Less than an hour after the first shots at

Bladensburg, the road to Washington lay open.

Amid the thick of the battle, a careful observer on the British

side might have spied a small, scholarly-looking gentleman, who had been

superintending the battle from just behind the American lines, wheel his

horse around and gallop away. The black-clad figure disappeared into the

dusty distance. President Madison had seen enough.

In Washington, panic already had begun to hold sway. Over the

past several days, many of the District’s inhabitants had come to realize

that disaster was imminent, and the streets were now choked with carriages

and carts ferrying refugees and their belongings—as well as a few being

used to rescue precious government property.

One valiant junior clerk, assisted by an African-American

office messenger, took it upon himself to safeguard the Senate’s most

important documents, including secret plans for the ongoing war. A State

Department employee rolled up the original Declaration of Independence and

Constitution to be stashed away outside the city. Yet many other

Washingtonians still refused to believe what seemed

inconceivable.

The battle for the city had been lost here as much as on the

field at Bladensburg—over the course of months and even years. It was lost

during session after session of Congress, when legislators refused to fund

an adequate army, relying instead on haphazardly trained militia. It was

lost when Madison chose an inexperienced political appointee to command

the region’s military defenses a few months before the invasion. It was

lost when Secretary of War John Armstrong refused to believe that the

nearby British fleet posed any danger to Washington. It was lost when the

Secretary of the Navy, sending urgent orders for reinforcements to

Philadelphia, inexplicably consigned them to the regular mail. (His letter

reached the post office on a Sunday.) It was lost when troops rushing to

join the army at Bladensburg were detained for hours in the capital while

a detail-oriented supply clerk made their colonel sign receipts for every

last gunflint. (They arrived after the battle was over.)

Last-ditch plans to defend the city on August 24 came to

nothing. Secretary Armstrong reluctantly let go of a scheme to conceal

heavy artillery and 5,000 infantrymen inside the Capitol. Deeds of valor

in the city that day would be civilian, not military.

That afternoon, as defeated troops from Bladensburg streamed

toward the capital, a 15-year-old slave named Paul Jennings was helping

set the table at the White House. Dolley Madison had requested places for

40 guests, as she expected her husband to return with his Cabinet members

and military commanders for a leisurely meal. Jennings put out fine silver

and china. As he and the other servants awaited the presidential party’s

arrival, hoofbeats sounded through the open window. Instead of the

distinguished guests, it was a messenger bearing news of the

rout.

More than any other Americans in 1814, James and Dolley Madison

could have claimed Washington as a place of their own creation. As father

of the Constitution, the President himself had devised the federal system

that provided—and still provides—its raison d’être. He had been among the

earliest advocates of the capital’s location on the Potomac River, and he

and his wife had been among its first prominent residents. Dolley Madison,

during eight years as frequent White House hostess under the widowed

Jefferson, then five years as First Lady, had brought to life the

capital’s social ecosystem. James Madison stands as founding father of one

version of Washington: the city of House, Senate, and Supreme Court.

Dolley’s spirit presides over another: the city of power lunches,

lobbyists’ receptions, and embassy parties.

Now the couple presided over Washington’s destruction, the

result of a war that the President had advocated and an invasion he had

done little to guard against. With her husband nowhere to be found, the

First Lady did all she could. She stuffed some White House silverware into

her handbag, grabbed her copy of the Declaration of Independence, and

asked Jennings and another slave to remove Gilbert Stuart’s portrait of

George Washington from its frame for easier transport. Then she locked the

front door and climbed aboard a waiting carriage. Among the last refugees

to leave the White House was her beloved pet macaw, carried out in the

arms of a slave.

An enduring myth of that day is that Dolley Madison cut the

Stuart portrait out of its frame. The painting shows no evidence of this.

Other oft-told stories about the burning of Washington rest on similarly

shaky foundations, including an anecdote about Cockburn and his officers

play-acting a legislative session in the abandoned House chamber, with the

admiral proposing from the speaker’s chair, “Shall this harbor of Yankee

democracy be burned?” I’ve found no firsthand British accounts of that

scene.

Much better documented is the banquet hosted at the White House

not long after Dolley Madison’s precipitous departure. Arriving at the

mansion, famished British soldiers were delighted to find the sumptuous

repast still laid out. After partaking generously of the food

and—especially—drink, they finished, in Lieutenant Gleig’s words, “by

setting fire to the house which had so liberally entertained them.” First,

many grabbed souvenirs, including the President’s cocked hat and dress

sword and his wife’s portrait. Cockburn joined in the fun with lewd jokes

at the First Lady’s expense. The cleanest one was when he grabbed the

cushion from her chair, quipping that he wished to “warmly recall Mrs.

Madison’s seat.”

Truth be told, more eyewitness accounts attest that the

redcoats’ behavior was restrained, even chivalrous—at least as much as

could be hoped of an invading army. With few exceptions—such as the

offices of a leading pro-war newspaper—Cockburn and Ross enforced a rule

that no private property should be harmed. Besides the White House, the

only residence deliberately burned was a house on Capitol Hill from which

some stray shots were fired, killing Ross’s horse from beneath him.

Officers torched the Treasury building but spared the Patent Office and

banks. Americans themselves burned the Navy Yard to keep its vessels and

supplies from falling into enemy hands; its storehouses full of lumber,

cloth, oil, and tar made an inferno rivaling that at the Capitol. A

detachment of redcoats followed up the next morning to demolish what the

first blaze had missed, and several dozen were killed and wounded after

accidentally igniting a cache of gunpowder.

Then, almost as suddenly as the British had arrived, they

vanished. Just after dark on August 25, barely 24 hours after they had

torched the Capitol, the invaders withdrew back toward Bladensburg and the

safety of Admiral Cochrane’s ships.

For those few inhabitants who had remained in the city, the

past two days’ events would linger as a set of surreal images, vivid in

color and blurry in outline. Almost 200 years later, despite all the

history the capital has seen since, their descriptions of the invaders

still possess the quality of lucid dreams.

One of the Washingtonians who recorded his memories was Michael

Shiner, a young slave apprentice at the Navy Yard. “As son as we got a

sight of British armmy raising that hill they looked like flames of fier,”

he wrote, “all red coats and the stoks of ther guns painted with red ver

Milon and the iron work shind like a spanish dollar . . . .” Shiner was

one of the last living witnesses to the tragedy of August 1814, surviving

for nearly another seven decades. He would carry those terrible days with

him for many long years, through emancipation, the Civil War, and beyond,

into a Washington vastly altered from the fledgling capital that the

redcoats had burned.

Adam Goodheart, director of Washington College’s C.V. Starr Center for the Study of the American Experience, is the author of “1861: The Civil War Awakening.”

This article appears in the August 2012 issue of The Washingtonian.