Washington’s tap water, most of which comes from the Potomac River, meets or exceeds federal water-quality standards. But new pollutants have emerged that are not removed by current water-purification technology. Evidence suggests that the same contaminants that caused massive fish kills and deformities in recent years are linked to increases in obesity, diabetes, autism, cancer, and other disorders—and that medications and products we use every day might contribute to the problem.

Of all the natural resources in the Washington area, none is

more important than the potomac river. Besides the beauty and recreation

it provides, the area pulls nearly 400 million gallons of water a day out

of it—about 90 percent of our drinking water.

In some ways, the Potomac is cleaner today than it was 40 or 50

years ago. Back then, people were warned not to swim in the river or eat

fish from it; a tetanus vaccination was recommended for anyone who did

swim there. On many days, you could smell the Potomac before you saw

it.

Improvements in wastewater treatment and conservation upgraded

the water quality of the river, which wends its way nearly 500 miles from

its origin in the Appalachian Plateau to Point Lookout, Maryland, where it

empties into the Chesapeake Bay. These efforts helped reduce major

pollutants—such as nitrogen and phosphorous from fertilizers, pesticides,

and soaps—that fed algae, rootless plant-like organisms that grow in

sunlit water. Algae blooms—rapid accumulations of microscopic algae in

water that can stretch for miles—deplete the water of oxygen and release

harmful toxins. They can virtually destroy a river if left to grow

unchecked.

Despite this progress, the river is not “clean.” In 2011, the

Potomac Conservancy, an organization that monitors the river, gave the

Potomac a grade of D, a drop from the D-plus the organization assigned it

in 2007. The conservancy noted that more than a third of the estimated

10,000 stream miles in the Potomac watershed are threatened or

impaired.

Even so, the drinking water in the Washington area is closely

monitored and meets or exceeds every Environmental Protection Agency

water-quality standard. But as some of the old pollutants have been

removed from the river, new ones have emerged that are not removed by

current technology and may be harmful to human health, especially for the

very young.

This emerging class of contaminants, called

endocrine-disrupting compounds (EDCs), a variety of natural and manmade

chemicals from many sources, first came to light in a dramatic way in the

summer and fall of 2002 with massive fish kills along the south branch of

the Potomac River in West Virginia, about 200 miles upstream from DC. Some

of the contaminants are new, and others have been discovered recently

because new measuring techniques permit scientists to identify EDCs in

minute quantities.

Says Luke Iwanowicz, a scientist with the US Geological Survey:

“Many of these emerging contaminants have been off our radar until now,

mostly because we did not have the ability to detect them.”

Jeff Kelble ran a fishing-guide business on the Shenandoah

River, long considered one of the nation’s great fishing rivers,

especially for smallmouth bass. The Shenandoah empties into the Potomac at

Harpers Ferry, West Virginia. Kelble remembers when fish were so plentiful

that they fought over his lures—it wasn’t uncommon for the sport fishermen

he guided to catch 50 to 60 fish in a day, all of which Kelble released

back into the river.

That changed in the last week of March 2004, when Kelble

learned that fish kills had struck the north fork of the Shenandoah. From

his boat, when the murky spring water was clear enough, Kelble could see

redbreast sunfish and smallmouth bass lying motionless on the

riverbed.

Kelble didn’t know what to make of the scene. Had a poison been

dumped into the river? Was this fish kill related to the kills that had

struck the south branch of the Potomac in 2002 and 2003? Had a large

quantity of milk somehow found its way into the water from dairy farms

along the riverbank? Milk has a voracious appetite for oxygen and might

have robbed the river of enough to kill the fish, but when the river’s

oxygen levels were measured, they were normal.

Kelble tried catching fish but had little luck. Finally, he

hooked a smallmouth bass.

“We were excited at first,” Kelble says, “but when we lifted

the fish out of the water, we saw it was covered with red sores that

looked like cigar burns, and it had lost many of its scales. I’d never

seen anything like it. I have an engineering degree—I’m not a

biologist—and I had no idea what was wrong. We caught a few other fish,

and almost all had similar sores on them.” Kelble caught more fish.

“Between 50 and 60 percent of the fish had lesions,” he says.

Kelble, now a conservationist with Potomac Riverkeeper—a

nonprofit that monitors river quality throughout the four-state Potomac

watershed—estimates that in 2004 and 2005, 80 percent of the adult

smallmouth-bass population was wiped out in the Shenandoah River. The bass

are back, Kelble says, but he still sees sick fish.

Vicki Blazer, a fish pathologist with the US Geological Survey

(USGS), had the job of finding the cause of the fish kills. Working out of

Kearneysville, West Virginia, Blazer led a team onto the rivers to collect

dead and dying fish. Electroshocks in the water stunned the fish and

brought them to the surface, where Blazer’s group netted them and put them

into water buckets to which an anesthetic was added.

As Blazer dissected scores of smallmouth bass, she was

surprised to find that many of the males had characteristics of both

sexes. Some 80 percent of the male fish had oocytes—precursors of egg

cells produced by females—in their testes, a condition known as

intersex.

Intersex among some species of fish is not unheard of but,

Blazer says, “you just don’t see this intersex phenomenon with

bass.”

Ed Merrifield, president of Potomac Riverkeeper, calls the

river fish kills “the canary in the coal mine.”

Our region is not alone. Fish die-offs have been reported in

waterways throughout the United States. Last September, thousands of white

bass died in the Arkansas River with no clear explanation. Beginning in

2008, fish kills and fish with lesions were seen in the upper James River,

and lesions were seen on the Jackson and Cowpasture rivers in Virginia as

well. Intersex fish also have turned up in the Great Lakes and the

Mississippi River.

Back at the lab, Blazer and her colleagues examined fish tissue

microscopically and discovered that some bass had bacterial infections

while others had fungal infections and still others were afflicted with

parasites. This finding led her to conclude that the plague killing the

fish wasn’t a toxin, a bacterium, or any single agent but resulted from

immune suppression that permitted opportunistic infections to flourish and

kill the fish.

“I think the fish kills were caused by the same chemicals in

the river water that are inducing intersex,” Blazer says. “Besides leading

to intersex, exposure to these chemicals, particularly estrogenic

hormones, depresses the immune system. The intersex occurs when the fish

are exposed to these estrogenic compounds at a young age.”

The study found that even bass with no signs of intersex

contained detectable levels of at least one endocrine-disrupting

compound.

Based on a USGS study published in Fish & Shellfish

Immunology in 2009, it appears that estrogenic compounds can lower

levels of hepcidin, an iron-regulation hormone found in mammals (including

humans), amphibians, and fish. Researchers believe hepcidin acts as a

first line of defense against certain disease-causing bacteria, viruses,

and fungi, which could explain why intersex fish and the fish kills

occurred at the same time.

Blazer and her colleagues published their findings in 2007 in

the Journal of Aquatic Animal Health. The report concluded that

intersex fish were “an important indicator of potential endocrine

disruption.”

What About Bottled Water?

As with tap water, where it comes from and how it’s processed are key. Read more.

Blazer has found intersex fish on both the lower and upper

branches of the Potomac and on both forks of the Shenandoah. She says the

fish kills and intersex are most prevalent along the most agricultural

areas of the rivers—where dairy, cattle, and poultry businesses reside—but

that those are probably not the only sources of the chemical soup that

kills fish.

Kelble says he saw the highest mortality in the upper reaches

of the Shenandoah, which are close to the highest-intensity animal-feeding

operations. The nine-county Shenandoah Valley has more than 900 poultry

farms, with more than 87 million chickens in Rockingham County alone. On

several occasions, Kelble and others have seen cattle herds wading in

tributaries of the Shenandoah. The residue of human and animal excrement,

which holds both natural and manmade chemicals, is considered a

significant source of EDCs. The USGS reported that a higher incidence of

intersex fish occurred in streams that drain areas with intensive

agricultural production and high human population when compared with

non-agricultural and undeveloped areas.

Blazer also has found intersex fish in the Conococheague Creek

and the Monocacy River in Maryland. She believes the intersex fish are the

result of a “toxic soup” of endocrine-disrupting compounds that are

finding their way into the Shenandoah and Potomac rivers. This mixture

comes from homes, farms, and industry and has been added to the water for

years. When it reached critical mass, tens of thousands of fish

died.

So what do dead fish 200 miles upstream from Washington have to

do with the quality of water we drink?

EDCs are a broad class of molecules that the EPA defines as

natural or synthetic agents that interfere with “natural blood-borne

hormones that are present in the body and are responsible for homeostasis,

reproduction, and developmental process.”

Natural hormones are secreted by endocrine glands into the

bloodstream and bind with specific cell receptors. Once bound, the

receptor carries out the hormone’s instructions, either modifying existing

proteins or directing the cell’s DNA to produce specific proteins. Because

EDCs mimic natural hormones and interfere with the endocrine system, they

can adversely affect normal growth, cognitive function, metabolism, and

reproduction in animals and humans.

Measuring their risk to human health has been hard because they

interact in complex ways at minute concentrations, both alone and in

combination with one another.

How they act in combination remains unclear. EDCs have been in

the environment in one form or another for more than 50 years and are

present in hundreds of millions of people worldwide. At last count, more

than 80,000 synthetic chemicals, mostly derived from petroleum and

vegetable sources, are in use today. The process of making these

synthetics involves toxic catalysts and reagents. Few of these 80,000

chemicals have been tested to determine what effect they have on

humans.

Individuals respond to EDCs in different ways, but one thing is

clear: Never before have humans had so many diverse synthetic chemicals

assaulting their bodies, a phenomenon some observers have called “the

largest uncontrolled science experiment in history.”

EDCs are present in many household items, such as

preservatives, plastics, cosmetics, and antibacterial soaps that contain

triclocarban, an endocrine disrupter that is flushed into wastewater and

ultimately into the river. Scented soaps and shampoos, hair-coloring

agents, skin creams, and sunscreen lotions contain them, as do some

spermicides, toilet papers, and facial tissues.

They’re also found in birth-control pills, hormone-replacement

therapies, and androgen-blocking or androgen-enhancing agents.

Chemotherapy and thyroid medications, antibiotics, and other prescription

drugs, some of which contain EDCs, enter the environment when they’re

excreted into wastewater and flushed down the toilet. Pharmaceuticals can

enter the water supply directly when unused pills are thrown

away.

In 2008, the Associated Press published a series of stories

entitled “Pharmaceuticals Found in Drinking Water.” The AP conducted a

survey of water quality and found that pharmaceuticals were present in the

water systems of two dozen major metropolitan areas. Washington’s drinking

water contained evidence of six drugs, including carbamazepine (an

antiseizure medication), monensin (an antibiotic used in animal feeds),

sulfamethoxazole (an antibiotic often given for ear infections), ibuprofen

(Motrin and Advil), naproxen (Aleve), and caffeine. Philadelphia’s

drinking water contained evidence of 56 drugs and byproducts. The AP

estimated that the health-care industry flushes 250 million pounds of drug

waste down drains each year.

In tests conducted by the USGS between 2003 and 2005, trace

amounts of 26 chemical compounds were detected in Potomac River water,

including the herbicide 2,4-D, a component of Agent Orange, and

insecticides including DEET. Atrazine, a chemical commonly used in weed

killers, has been associated with intersex in amphibians and has been

found in many rivers, including the Potomac. Studies revealed that male

frogs exposed to atrazine produce eggs in their testes, the same

phenomenon seen with intersex fish.

EDCs also enter the Potomac watershed from antibiotics and

synthetic hormones given to cattle and poultry to prevent disease and

stimulate growth. Once excreted by the animals, the chemicals find their

way to the river, usually via rain runoff. In Shenandoah and Potomac

tributaries upriver, cattle are allowed to walk into the water, a form of

“direct deposit,” Blazer says.

“We don’t have smoking guns that tell us what specific

chemicals may be causing problems in the river,” says Potomac

Riverkeeper’s Ed Merrifield, “and it could take years to find out what

chemical or chemicals cause intersex fish.”

Even if we could identify potentially dangerous EDCs, current

municipal water-filtration methods in our area cannot remove them, nor

does the EPA require them to. A recent USGS study of several rivers

nationwide, including the Potomac, reported the same concentrations of

some compounds in the river water before and after it went through the

filtration process.

Many of the EDCs that flow into the Potomac River and other

bodies of water are thought to be estrogenic, meaning they mimic estrogen

hormones in the body.

“Estrogenic compounds are important, but they are just part of

the picture,” says the USGS’s Luke Iwanowicz. “We have also found

androgenic compounds in the river that we suspect come from livestock

feeding, and we’d like to find out what else is in the river. A lot of

people throw away anti-inflammatory medications, and I also want to see if

there are thyroid hormones in the river. I’d be shocked if there

weren’t.”

“The exposure to EDCs that we get just from drinking water is

probably a very low level,” Blazer says, “but we know EDCs get past the

placental barrier and enter the embryo, when the organism is most

sensitive, and this is when we really need to worry because very low

levels at those times will have a harmful impact. The changes initiated by

EDCs may not show up until the person goes through sexual maturity or

later. There are all sorts of things we don’t understand right

now.”

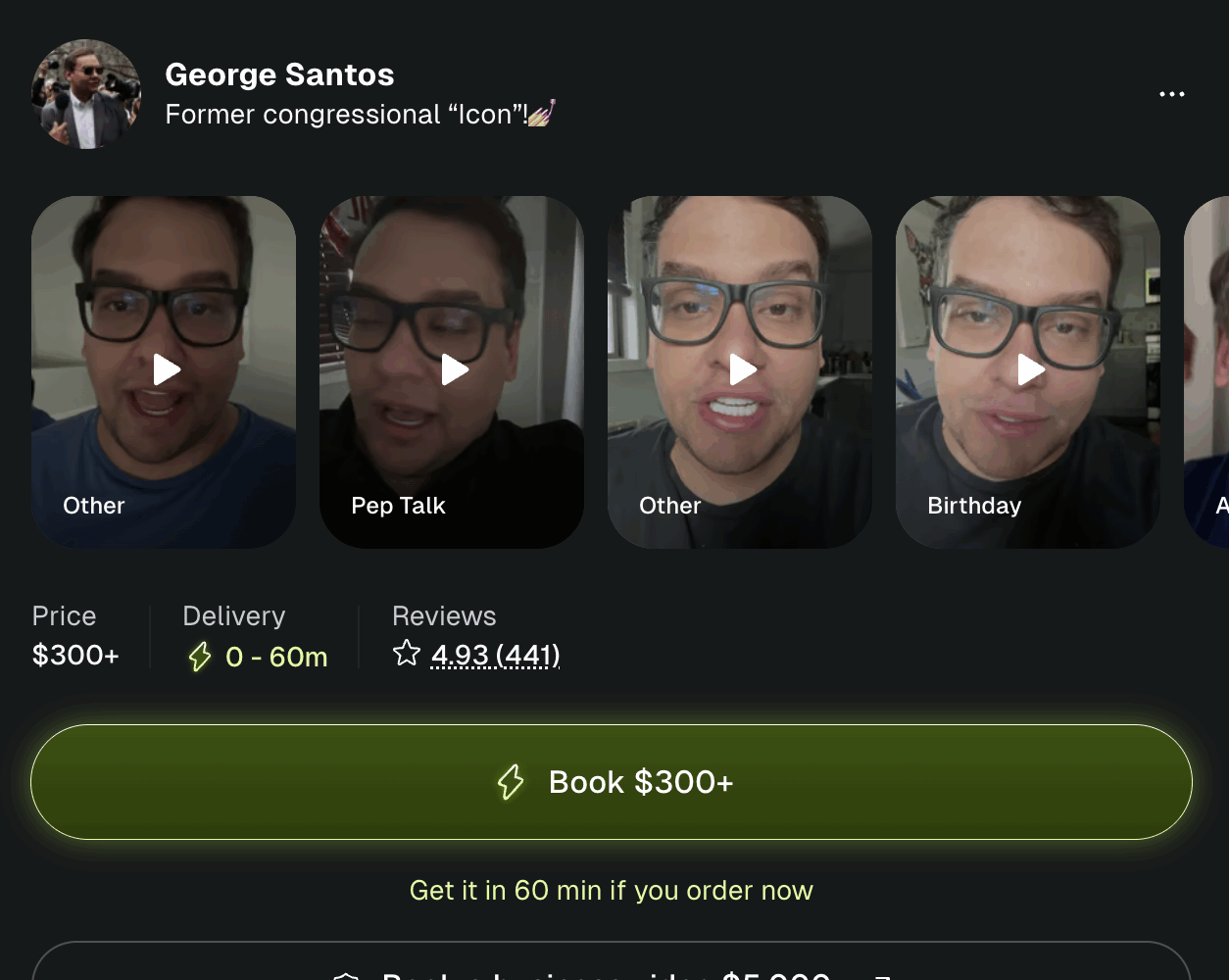

Check Your Beauty Product Labels

Many products contain EDCs that can remain in the water coming out of your tap even after it’s been treated. Read more.

In time, the impact of EDCs on humans will be better

understood. The technology for measuring human exposure to synthetic

chemicals has advanced in recent years. Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention (CDC) labs now can monitor human blood and urine for more than

200 so-called halogenated and non-halogenated chemicals and their

metabolites. These include pesticides and chemicals used in cosmetics,

perfumes, detergents, toys, plastics, and fire retardants. But the ways in

which different EDCs might combine in the human body will likely remain

uncertain for some time.

The Washington Aqueduct, headquartered on MacArthur Boulevard

in Northwest DC, is the major supplier of drinking water for the District

and parts of Northern Virginia, including Arlington and Falls Church. The

aqueduct distributes some 160 million gallons of drinking water a day, and

on hot days up to 180 million gallons.

The Washington Suburban Sanitary Commission, in Maryland,

distributes water from the Potomac to homes and businesses in Montgomery

and Prince George’s counties and has two reservoirs on the Patuxent River

that distribute water to parts of Prince George’s.

Fairfax Water serves Fairfax County and Alexandria; 55 percent

of its water is drawn from the Potomac and the remaining 45 percent from

the Occoquan Reservoir. These are the area’s three major suppliers of tap

water.

Tom Jacobus, general manager of the Washington Aqueduct, says

current water-filtering technology doesn’t neutralize EDCs that enter the

system from the river’s intake pipes, but he notes that those levels are

very low.

“The problem right now is we don’t know the effect of very low

levels of EDCs on human health,” Jacobus says. “So we are trying to decide

what kinds of water treatments we may need to go after some of these

endocrine-disrupting compounds. Right now I can say without qualification

that our drinking water meets all federal standards and therefore is safe

to drink. But that is not a good enough answer, because safe enough for

whom? So we are looking into the possibility of installing ozone UV [a

technology that has the capacity to remove many EDCs from water] to

further ensure that we can neutralize the anthropomorphic activity of EDCs

in the water, but there are significant costs to this and other new

technologies as well.”

The Blue Plains Advanced Wastewater Treatment Plant, in

Southwest DC, the world’s largest such plant, treats and discharges 370

million gallons of Washington-area wastewater a day—up to a billion

gallons during rainstorms. Untreated water is piped in from the District,

suburban Maryland, and Fairfax and Loudoun counties and is pumped back

into the Potomac River after it undergoes tertiary treatment. Says George

Hawkins, general manager of the District of Columbia Water and Sewer

Authority: “We put back water into the Potomac that is often cleaner than

the water in the Potomac. It is a remarkable technical

achievement.”

But just as the Washington Aqueduct doesn’t filter out EDCs,

neither does Blue Plains or upriver wastewater-treatment plants in

Rockville and Poolsville, whose treated wastewater goes into the Potomac

and finds its way to the Washington area’s water-intake pipes, to be

recirculated through our freshwater supply.

Hawkins, former director of DC’s Department of the Environment,

says the water industry is paying a lot of attention to EDCs. A local

group formed to investigate the issue decided that not enough science is

currently available about EDCs to justify the expense of trying to remove

them.

“We need to know which of these new contaminants may pose the

greatest health dangers so we can develop a plan,” Hawkins says, “because

right now our ability to detect these chemicals as low as one part per

trillion has outstripped our ability to know what their consequences may

be. But does this issue of endocrine disrupters keep us awake at night?

You’re doggone right it does.”

In the best of all worlds, the Clean Water Act of 1972 might

have eliminated the EDC problem in the water supply before it began, or at

least reduced it, because a goal of the act was to prevent all manmade

pollution from entering our waterways. While that law has led to

improvements in the quality of many of our nation’s waterways, it is also

routinely ignored. According to EPA data reported in the New York

Times in September 2009, between 2004 and 2009 there were 506,000

violations of the Clean Water Act nationwide.

In 1996, Congress created an EPA office dedicated to EDC

research, called the Endocrine Disruptor Research Initiative. It has yet

to release significant information about the risk of EDCs to metropolitan

drinking water.

Now that we know our drinking water contains EDCs, here is the

question: Even at the very low concentrations that EDCs reach Washington’s

water-intake pipes, is there evidence that they pose human health

consequences? If so, what are they?

Two of the most remarkable aspects of the current obesity

epidemic are its scope and the rapidity with which it has grown. Between

1980 and 2008, obesity rates have doubled worldwide, according to a study

published in the British medical journal the Lancet, and other

studies have shown a threefold increase in North America and Europe. The

epidemic cuts across socioeconomic, age, and sex lines.

In 2000, no state in the US had an adult obesity rate higher

than 30 percent, according to the CDC. By 2010, 12 states had reached that

level, and another eight states are close. It’s estimated that more than a

third of adult Americans are clinically obese and that 68 percent of

Americans age 20 and older are overweight or obese.

Obesity is considered a threat to human health by the National

Institutes of Health and the World Health Organization. WHO says more

people in the world now are obese than are undernourished. A risk factor

for Type II diabetes, cardiovascular disease, stroke, and high blood

pressure as well as for breast, colon, and renal cancers, obesity is a

major force driving up health-care costs.

Why have we gotten so fat so fast? In children, the rapid rise

of obesity and Type II diabetes has been linked to everything from too

much TV and video games to fast food and the lack of physical education in

schools. A recent WHO statement lays the blame on less exercise coupled

with increased consumption of “nutrient-poor foods” with high levels of

sugars and saturated fats.

All of these factors probably are contributing to the rise in

obesity, but until recently no one linked the epidemic to the disruption

of hormonal regulation, which can change our bodies and diminish our

ability to stabilize weight.

A 2009 statement issued by the Endocrine Society, called

“Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals,” found “alarming signals” that EDCs may

be triggering obesity and other serious health problems. In many if not

most cases, research indicates that prenatal and early childhood are the

most vulnerable periods because exposure can affect development. Health

problems may not be seen until many years later; this situation has given

rise to an area of scientific inquiry called “the developmental origins of

adult disease.”

The report noted that the increasing incidence of obesity

matches the rise in industrial chemicals in the environment, and it cites

a number of scientific studies linking certain EDCs (called obesogens) to

obesity.

The first-of-its-kind statement went through “incredible

scrutiny,” says Dr. Andrea C. Gore, one of the coauthors. It’s 54 pages

long and lists 485 scientific papers to support its claims that EDCs

appear to be triggering obesity and other human-health problems, including

diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

Says Gore, a professor of pharmacology and toxicology at the

University of Texas: “We felt there is a very strong weight of evidence

supporting the link between endocrine disrupters and dysfunctions in all

the endocrine systems in humans and wildlife. Much of that is based on

very good lab research that has been coming out in recent years. So the

reason we were able to make such a strong statement is that the data

really support it.”

The report says: “The literature demonstrates a role of EDCs in

the etiology of complex diseases such as obesity, diabetes mellitus, and

cardiovascular disease, yet these processes are still poorly

understood.”

The report goes on to explain that “even infinitesimally low

levels of exposure—indeed, any exposure at all—may cause endocrine or

reproductive abnormalities, particularly if exposure occurs during a

critical developmental window.” Surprisingly, the report found that “low

doses may even exert more potent effects than higher doses.”

Because EDCs are ubiquitous in the environment, it’s unclear

whether those we get from drinking water play a prominent role in human

health, but a reasonable assumption based on the fish kills and other

evidence is that they could.

EDCs have also been linked to the rising rates of breast and

prostate cancers, both of which are hormone-related. There are undoubtedly

many environmental and genetic factors involved in cancers, but one of the

strongest pieces of evidence for the role of EDCs in prostate cancer came

out of a large epidemiological study conducted by the National Cancer

Institute and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. The

study evaluated more than 55,000 agricultural pesticide applicators in

North Carolina and Iowa and found that exposure to pesticides, some of

which may interrupt normal hormonal balance, increased prostate-cancer

rates in men with a family history of the disease, leading the authors to

speculate that the pesticides interacted with genes in those

men.

According to the Endocrine Society paper, several signals

suggest that people may be at risk for reproductive compromise because of

EDCs. Declining male sperm counts reported in countries around the world,

including the United States, may be linked to EDC exposure, the report

says. Additionally, young women in the 15-to-24-year-old group currently

have the fastest-growing rate of involuntary subfertility. Subfertility

doesn’t mean that a woman can’t bear children but that she may encounter

more difficulty and delay in becoming pregnant than would otherwise be

expected.

There are some indications that hypospadias, a malformation of

the urethra, may develop in a baby boy when a genetic susceptibility is

triggered by environmental exposure prior to pregnancy or within the first

16 weeks of fetal development, the time when the urethra develops.

Epidemiologic studies suggest that environmental exposures increase the

incidence of hypospadias and other birth defects.

According to the CDC, metabolites from one type of phthalate

were found to be five times higher in the urine of American women ages 20

to 40 than in any other segment of the population. Phthalates make

plastics flexible and are used in perfumes, nail polish, and shampoos. The

phthalate from the study, dibutyl phthalate, has been found to be

estrogenic in laboratory animals, leading to developmental disorders in

male offspring. It also interferes with the thyroid system.

A study in the United Kingdom found that the male children of

vegetarian mothers, who consumed more phytoestrogens from agricultural

fertilizers than mothers on regular diets, had five times the rate of

hypospadias as the sons of nonvegetarian mothers.

Many theories have been advanced to account for the increasing

prevalence of autism in children, a disorder the Autism Society of America

calls “the fastest-growing development disability” in the world. A CDC

report in the June 2011 issue of Pediatrics reported that the

percentage of children and teens in the US diagnosed with developmental

disabilities such as autism has increased by 17 percent since the late

1990s. This upward trend of neurological impairment was also seen in the

increased prevalence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder as well

as stuttering and learning disabilities.

While genes probably play a role, there is growing suspicion

that EDCs are also involved in a range of neurological impairments,

including autism.

Gore notes that autism is a complicated disorder and has no

single cause. But, as with obesity and hormone-related cancers, she says,

“the timing of autism’s increase in the population also coincides with the

rise of EDCs in the environment. We don’t want to overinterpret the data,

but the ways in which we’ve changed the environment appear to be changing

how our brains develop. Low-dose exposures in early development are very

important and very potent, but the problem is it is hard to detect

them.”

For example, a large body of evidence from the Great Lakes and

other areas links maternal polychloride byphenyl (PCB) exposure, largely

from fish consumption by mothers during pregnancy, to lower IQs in

children. One avenue by which PCBs are believed to do this damage is

through thyroid disruption. Normal thyroid function is vital to proper

neurological development.

“A loss of four or five IQ points may not seem like such a big

deal,” Gore says, “but when you consider the whole shift of the

population’s IQ because people are being exposed to these contaminants,

there could potentially be a dumbing-down of the population.”

Once used widely by industry for many purposes, including as a

lubricant and coolant, PCBs were banned in 1979 because of environmental

concerns. Made by combining benzene and chlorine, PCBs—which are

classified as endocrine disrupters—sink to the bottoms of rivers and

lakes. They enter aquatic plants and, when fish eat them, become part of

the human food chain. When people consume them, they get stored in

fat.

PCBs also aerosolize—meaning they break down over time and can

turn into a fine, powdery substance carried by wind—and as a result are in

virtually every body of water in the world, including the Potomac River.

The EPA has issued a PCB advisory warning against the consumption of fish

from the Potomac, especially of bottom feeders such as carp and

catfish.

Scientific studies show that salmon raised in fish farms in the

Atlantic Ocean have a heavier burden of PCBs than salmon caught in the

wild—in part because farm-raised salmon don’t swim as vigorously as those

in the wild and as a result have more body fat. Although there are fewer

PCBs in the environment than before, because of their long half-life they

continue to pose a danger to humans, especially during early

development.

The best way to prevent EDCs from entering Washington’s

drinking water would be to keep them out of the Potomac River in the first

place. Tom Jacobus notes that the Potomac River Basin Drinking Water

Source Protection Partnership was formed by area water utilities in 2004

to address this issue. Although the body has no enforcement powers, it’s

working with the Environmental Protection Agency and agricultural

extension services in the states to raise awareness of the consequences of

such practices as allowing cattle, especially those treated with hormones,

to roam freely in tributaries. Efforts are also being made to convince

cattle and chicken operations to control runoff into the river. Jacobus

says the message is simple: “If you have a cattle-feeding operation that

uses a lot of hormones, please don’t let the cattle have access to the

water, and control your runoff.”

Jacobus says the best way to keep EDCs from the river is not to

put them there in the first place. “I would also ask people not to throw

your pills down the toilet and to look at labels on personal-care products

and avoid those that may have EDCs in them.” This is an important message

but one unlikely to be heeded by most people.

Because there are hundreds if not thousands of chemical

compounds, Jacobus says, water officials are trying to get a clearer

understanding of the classes of chemicals and to regulate them: “We are

looking at new and innovative treatment techniques, and within two years

we will have treatment plans for some EDCs. We need to determine as an

industry what these treatment levels should be, and we need to look at

cost-effectiveness. Some of these EDC-removal technologies could cost $100

million. Ozone treatment, for example, works through electricity, so it’s

expensive to operate. We’re not resisting this, but we don’t want to get

ahead of the science.”

For now, Jacobus says, the Washington Aqueduct will continue to

monitor the EDC issue. “We have a lot of confidence in the EPA, but at the

same time we want to do better than EPA regulations because our customers

want to us remove some of the unknown,” he says. “We are also involved in

a cooperative research project to understand more about

endocrine-disrupting compounds and their role in drinking

water.

“From the science we know now, we do not see a threat to

drinking water at levels we can detect. But are we looking at it and

thinking of future treatments? Yes, we are.”

Contributing editor John Pekkanen has written about health and medicine for more than three decades. His September 2011 article, “Coming Back: Battling the Invisible Wounds of War,” about military servicemembers with brain injuries that would have been fatal in earlier times, can be found here.

This article appears in the July 2012 issue of The Washingtonian.