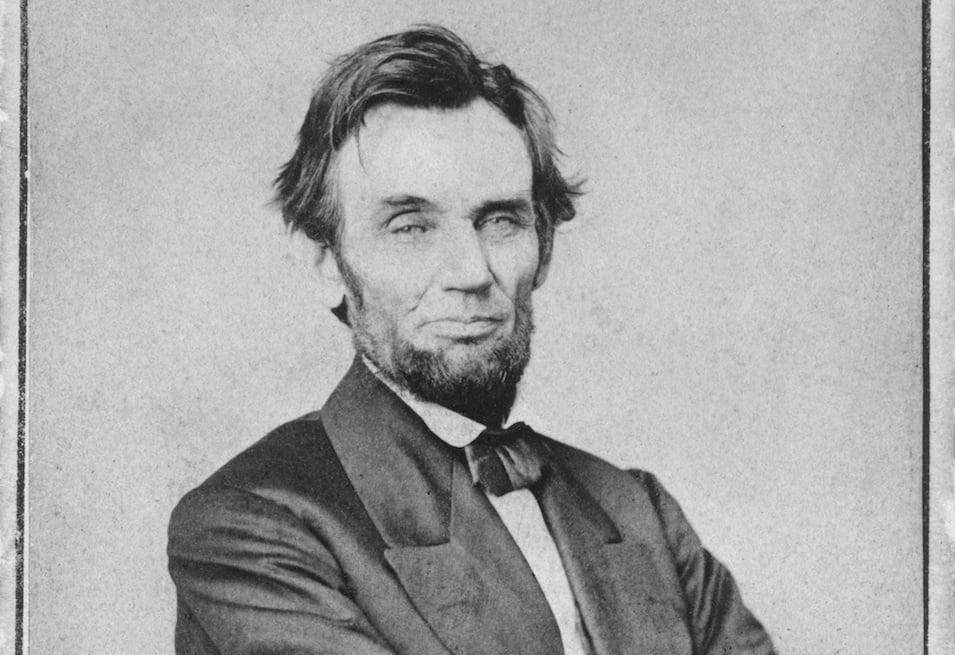

No American president has ever matched the iconographic ethos of Abraham Lincoln. History wouldn’t be the same without his face; it’s etched onto the five dollar bill, Mount Rushmore, and a towering memorial.

An HBO documentary called Living With Lincoln, which premiered Monday at 9 PM ET, looks into the significance of his imagery. Peter Kunhardt, who directed the film and worked on it alongside sons George and Teddy, narrates his family’s obsession with Lincoln photographs. Lincoln was the most photographed man of the 19th century, and the Kunhardt family came to hold hundreds of those photos.

Their collection began over a century ago with Kunhardt’s great-grandfather, Frederick Hill Meserve, whose father met Lincoln after the Battle of Antietam in 1862. Years later, Meserve started amassing the President’s photographs. “Photography was only taking off the in late 1850s and 1860s, so [Meserve’s] timing was ideal,” Kunhardt says. “Lincoln had a very good sense of self-promotion in knowing he needed it in his political career. He purposely sat down for lots of photographs. Other people just weren’t doing it in those days to the degree he was.”

“[Lincoln] was the man about town, certainly during the Civil War, in Washington,” says James Barber, a historian from Alexandria who curates exhibits at the National Portrait Gallery. “He would walk down to photography galleries and sit for a few photographs. He liked doing this. It was a chance for him to chat with a photographer. It was a way for him to slow things down.”

Meserve went on to consult on Lincoln’s likeness for his memorial. He also contributed the portraits used to etch Lincoln onto the five dollar bill, the penny, and Mount Rushmore. “There was a fervor about memorializing him,” Kunhardt says. “[Meserve] was the one they turned to to get a clear image of what Lincoln looked like. He was a conduit through which research was done.”

He eventually brought together a staggering collection of Lincoln memorabilia. The Yale Beinecke Library recently purchased 68,000 images, in addition to thousands of prints, books, maps, and other documents. Barber helped the Kunhardts develop a numbering system to organize their collection. (The Portrait Gallery currently houses 5,000 glass plate negatives purchased from the Kunhardt family.)

Living With Lincoln delves into the President’s fascination with portraiture but also centers on Kunhardt’s grandmother’s dedication to her father’s Lincoln fixation, as well as her aspirations as a children’s book author. Despite depression and the weight of what had become a familial duty, she held firm in her commitment to the collection.

“The [film’s] message was bigger than Lincoln and bigger than our family,” Kunhardt says. “At the core of this is life-work balance.” For Barber, the endurance of Lincoln’s legacy is as much about the President himself as it is about those who spent decades materializing it. “That’s the one very interesting characteristic about the man: He wasn’t handsome, and he wasn’t much to look at, but he almost seemed to be fascinated by the photographic process,” Barber says. “He was a man who was very concerned about how history would remember him.”