Late-night comic Jimmy Kimmel’s last appearance on ESPN’s Monday Night Football climaxed with this comment, which got him banned from the show:

“I’d also like to welcome Joe Theismann, watching from his living room with steam coming out of his ears.”

Kimmel had it right about Theismann watching the Giants/Falcons game on October 15 from his home in Leesburg. Theismann had been let go in March after hosting ESPN’s pro-football broadcasts since 1988. But he was only half right about the steam.

“I’m much more at peace with it,” Theismann told me.

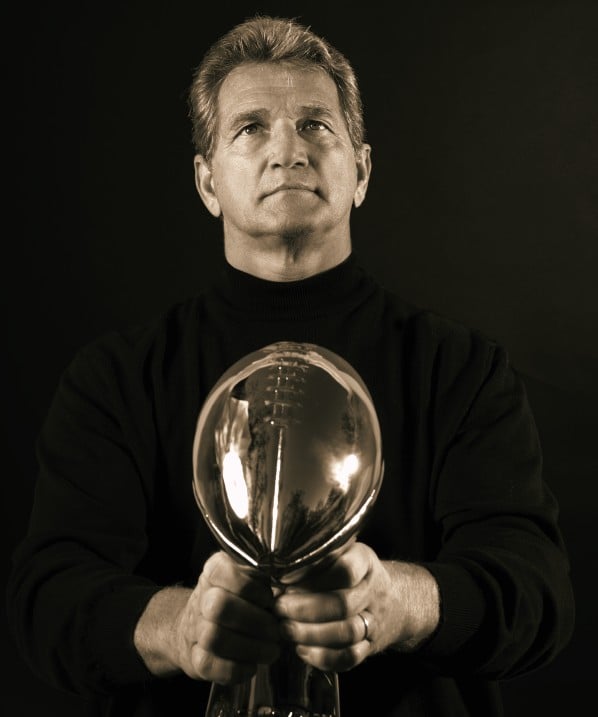

In a pair of interviews—one at his office, JRT Associates, in Sterling, another at his farm outside of Leesburg—the legendary Redskins quarterback and veteran broadcaster talked about his days on the gridiron, his career in broadcasting, his painful departure from ESPN, and his relationship with Tony Kornheiser, the former Washington Post sports columnist who now tries to crack wise from the Monday Night Football booth.

Washingtonians take their Redskins quarterbacks to heart. Sonny Jurgensen? People love the quarterback turned local broadcaster. Joe Theismann splits the town: Some love him, some don’t. Mention his name, and people are quick to say “too cocky.”

“And I talk too much,” Theismann says. “I was egotistical and self-centered in my early years. I’m not proud of that. After people actually meet me, they’ll say, ‘You’re really not the prick I heard you were.’ ”

Joseph Robert Theismann was born September 9, 1949, in New Brunswick, New Jersey. His Austrian father, Joseph John Theismann, ran a gas station and worked in his brother’s liquor store. His mother, Olga Tobias, is Hungarian. She worked for the Johnson & Johnson health-products company until her retirement. Joe’s parents now live in Florida.

Says Theismann: “I was a little bit of a hellion, like my dad.”

At South River High, Theismann lettered in baseball, basketball, and football. Though the family name is pronounced Thees-man, Joe was up for the Heisman Trophy in 1970 after a stellar year as quarterback at Notre Dame. Theismann says Notre Dame’s PR director changed his name to rhyme with the prize (Thighs-man). He finished second in the voting to Jim Plunkett of Stanford University.

Theismann came to the Redskins in 1974 after three seasons in the Canadian Football League. In 12 Redskins seasons, he threw 3,602 passes, completed 2,044, and racked up 25,206 yards through the air—all franchise records. He passed for 160 touchdowns and played in 163 straight games.

He returned punts his first two seasons and didn’t get the QB job until Jack Pardee named him starter over local hero Billy Kilmer in 1978. He would take the Redskins to the playoffs three times in the 1980s and to two Super Bowls with coach Joe Gibbs, including a 27–17 victory over the Miami Dolphins in 1983.

Theismann’s trademark was a combination of “flamboyance, charisma and cockiness,” Michael Richman writes in The Redskins Encyclopedia, but above all he was a competitor. Playing the Giants late in the 1982 season, he threw four interceptions and got his two front teeth knocked out in the first half. With his team down 14–3 in the second half, Theismann delivered a crushing block that freed running back Joe Washington for a 22-yard touchdown. The Redskins won 15–14.

Google “Joe Theismann” and you will find videos of the 1985 injury that essentially ended his career. Playing in the Monday Night Football game, Theismann dropped back to pass. Giants linebacker Lawrence Taylor jumped on his back just as another Giant hit his leg, breaking the fibula and the tibia.

“I learned after the broken leg that it can be a very lonely world out there,” Theismann says. “Life is not about you; it’s about relationships.”

His Redskins career over, Theismann eagerly went into TV broadcasting. In 1985, before the injury, ABC sports czar Roone Arledge chose him over O.J. Simpson to join Frank Gifford and Don Meredith in the booth for the Super Bowl—the seat that the legendary Howard Cosell had vacated.

Theismann worked for CBS in 1986 and 1987 before moving to ESPN in 1988 to broadcast the new cable channel’s Sunday-night football games. He helped anchor ESPN’s NFL broadcasting team until the beheading in March of this year.

Off the field and out of the booth, Theismann kept gossip columnists busy. His marriage to Shari Brown Theismann ended in divorce in 1984. They had three children: Joe, Amy, and Patrick, all of whom are married. His seven-year relationship with actor/TV host Cathy Lee Crosby was the stuff of tabloid columns. His second marriage ended in divorce after three years.

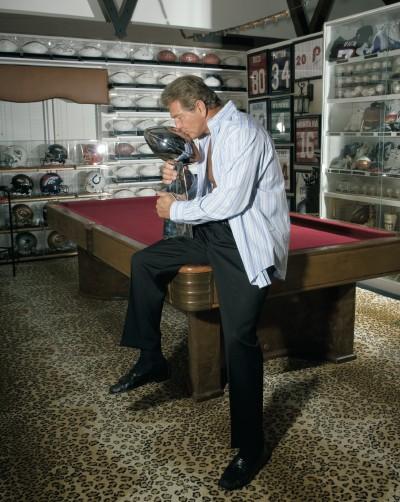

Theismann has been married to Robin Smith for 11 years. She describes herself as “a country girl from Memphis.” They met at a convention where she was representing Helene Curtis haircare products. They live in three homes: a 100-acre spread north of Leesburg near Waterford; his residence in Memphis; and a home in Florida’s panhandle, not far from Joe’s daughter, Amy, who has five children. His son Patrick lives in DC with his wife, Sharon. Joey lives with his wife, Lynn, and their two children in Gainesville, Virginia.

Did getting canned by ESPN hurt as much as the broken leg?

“I think I will be able to recover from this blow mentally much easier than from getting my leg broken,” he says. “You have to get humbled before you get humble.”

Don’t cry much for Joe. He gets paid $25,000 a speech. In the middle of our first interview, his assistant, Sandy Sedlak, slid settlement papers across the table for Theismann’s signature. His deal with ESPN was $8 million for five years. He was less than two years into the contract.

I asked what the settlement was worth. “Can’t say,” he responded. About $4 million is a good guess.

Theismann did smile when he signed the papers.

Being out of the football broadcasting booth must be a shock. What’s your next move?

Football kept me busy for 37 years. It’s really the first time I’ve had a fall where I haven’t worked a minimum of 50 hours a week. This year is a major adjustment for me.

What’s been the hardest thing?

I’ve never been cut. I’ve never had somebody tell me, “I don’t want your services.” I have an ego, just like everybody else, and my ego gets bruised. It got the crap kicked out of it. I was raised on a principle that if you work your butt off and you’re good at what you do and the people you work for tell you you’re good at what you do, then common sense says you’re going to keep your job.

Tell me how it went down.

I was called to a meeting in New York by John Skipper and Norby Williamson, two top ESPN executives. I had an inkling something was going on because in all my years with ESPN, I’ve never been called to a meeting at that level. It’s always been with my producer and my director, so I had a feeling something was going down.

Everybody thought Tony would be leaving. They said there was going to be a change, and the first thing that goes through your mind is, “Oh, that’s a shame. It’s going to be somebody.” And then all of a sudden it’s you, and you’re like, “Whoa, wait a second, me?”

What did you say?

John barely got the words out, and my immediate question was, “Was it the quality of my work?” He said no. At that point, I felt like it was something I couldn’t control. And if I couldn’t control it, I could sit there and talk until I was blue in the face, but they’d made a decision, and that’s the way it was going to be.

Let’s talk football. What has been your involvement with the Redskins?

The fans have been wonderful to me, and so have the coaches. I’ve had full access to practices. I’ve sat and talked with Jason Campbell, trying to share any information with him about being a quarterback for the Washington Redskins, because I think it’s unique. You look at the history of the people that have been here between Sammy [Baugh] and Sonny [Jurgensen] and Billy [Kilmer] and myself. . . .

You were the last quarterback to stick with the team.

There have been 22 starting quarterbacks in Washington in the 22 years I’ve been away from the game. In tenure, as far as consecutive starts, I think I’m second to Sammy Baugh. We’ve had guys go through here like you wouldn’t believe, but that had to do with the fact that the supporting cast wasn’t very good.

Why has there been so much turnover?

Turmoil at the coaching level and constantly changing philosophies. Constantly changing personnel. Quarterbacks wind up paying the price for the instability.

What did you say to Jason Campbell?

I talked to him about his mechanics. In Jason’s defense, in the four years he was at Auburn, he had four different offensive coordinators—four different people telling him how to do something. Then he comes to the Redskins, and he has two more.

Do you think Campbell will succeed?

I like a lot of things about Jason. I like his toughness, I like his demeanor, I like his accuracy, I like his composure, I like his leadership skills. He steps into a huddle, and guys pay attention. I’ve been at practice, where you see how a guy can lead a football team. If things aren’t going well, is he going to step up and rally the troops so coach doesn’t really get pissed off? He has every ingredient and every quality you would look for in a kid who can be a star.

Why are the Redskins so ingrained in Washington’s psyche?

George Allen had a lot to do with the identity of the Redskins. He took them to the Super Bowl in 1972, and you had characters like Billy and Sonny. You might as well be talking about the Wild West and the James brothers: hard living; two very, very different people. And I learned from both of them.

But you and Billy and Sonny didn’t hit it off.

To be honest, Billy and I never got along. We never liked each other. He had something I wanted, and he had something he didn’t want to give up. I think it got personal. Since then, it’s water under the bridge. We see each other places and play golf in tournaments. We’re cordial, but there was a competitiveness there.

What about you and Sonny?

Sonny and I never had much of a relationship, good or bad. Sonny was the best passer I’ve ever seen. I distinguish between passers and throwers. Throwers are guys who throw the ball hard; passers are guys who are just poetic. He could throw it down the field perfect, or he could throw it five yards perfect.

Billy, on the other hand, couldn’t throw it to save his life. But it was amazing to watch men play for Billy. It was almost like the football team knew that Sonny could deliver without them, and it’s like the football team felt like, “You know what, Billy, we’re going to help you.”

With Kilmer and Jurgensen on the field, how did you become quarterback?

I returned punts the first two years as a Redskin. I snuck on the field. I snuck up behind George Allen—the regular kick returners Herb Mul-Key and Kenny Houston had gotten hurt—and I said, “Kenny’s hurt. You want me to go in and return punts?” And he said, “Yeah, go ahead.”

So I ran by him, and he turned to Paul Lanham, the special-teams coach, and said, “What’s he doing out there?” Paul said, “You sent him in to return punts.” And George said, “No, I didn’t. Get him off the field.”

I never came off.

Who taught you the most about football?

George Allen’s philosophy was run the football, play great defense, don’t make mistakes, and you’ll win games. That hasn’t changed in forever. George was the one who came up with the nickel package and using five defensive backs. He was the one who created the position of special-teams coach. The man was a true innovator.

But the guy I’m forever indebted to is Jack Pardee. He was the man who made me the starting quarterback of the Redskins. And Joe Walton, who was my quarterback coach and coordinator, taught me how to play the position. And Joe Gibbs provided me with an opportunity to play within a system that really showcased my strengths.

Did the camaraderie and roughneck spirit of the Redskins in the 1980s, when Jack Kent Cooke owned the team, create a kind of glue and help make them so successful?

Absolutely. That’s why I called that group of guys the characters with character. When we arrived in Pasadena for the Super Bowl in 1983, the linebackers had all put on battle fatigues on the plane because they were going to war. The wide receivers—Charlie Brown, Virgil Seay, and Alvin Garrett—were called the Smurfs. They went off to Disneyland with the little purple guys from the Smurfs TV series. Riggins? John was John. Friday night before the Super Bowl, at Mr. Cooke’s party, John’s in white tails, cane, top hat, tux, and I think a pair of shorts and cowboy boots.

Sounds as if you had a blast.

Oh, yeah. We had the 5 o’clock club, where the offensive linemen and Riggins would go drink after practice. George Allen used to have cake and ice cream and milk for us on a Friday afternoon if we had won. Joe changed that to barbecue. We’d have a big barbecue on Friday. When practice was over, you could hang around. Guys didn’t race away from the park like they do.

What kind of locker room did Gibbs run?

Back in the beginning, he never came to our locker room. I played for Joe Gibbs for 41⁄2 years. I can count on one hand the number of times he walked through our locker room. He wanted the football players to own their locker room. He didn’t want to police us, he didn’t want to babysit us, he didn’t want to know what was going on in there. He really treated us like men, and that’s what he tried to do with this team today. He’s tried very, very hard to get the players to take over the locker room. But because of free agency and the turnover, you don’t establish that. You don’t have guys who’ve been there six or seven years.

Who kept order?

Dave Butz, one of the first 300-pound defensive linemen, was the enforcer. You didn’t mess around with Dave. If there was a guy screwing around, the players would come around and say, “You need to get your act together; we don’t tolerate this.” You want to create an environment where guys want to hang around. You build the character of a football team away from the field.

Is that happening now with the Redskins?

It’s starting to, but the big question that will loom is Joe. He’s got one year left on his contract. Will there be a coaching change?

I think Joe will fulfill his contract, but I don’t think he’ll go past that. Dan Snyder might have to look at a five-year extension, and I don’t know if Joe would want to go into his seventies. Taylor, his grandson, is not well, and there are lots of family issues. Joe is a very strong family man, a very strong Christian, and he has family issues that he feels like he should attend to more than a football team. Joe Gibbs has brought back professionalism; he’s brought back pride, a work ethic, class. He’s basically given Dan everything that Dan could want with regard to the way a professional organization should be run. The thing he hasn’t been able to do is deliver a championship.

How about just a winning season?

We were 10–6 two years ago, but the one thing he hasn’t been able to do is get this football team to a point of dominance. The Cowboys right now are the best team in the NFC. The three best teams in football are New England, Indianapolis, Dallas.

Would you consider being coach?

I wouldn’t be qualified to coach; I haven’t had the experience. Coaching is like teaching.

I think I’ve had the experience from a personnel standpoint to run an organization. I’ve spent a lot of time talking to people who’ve owned teams, trying to understand from an ownership perspective what they’re looking for in a ball club. The challenge of building something would be exciting. I don’t want to get away from the game of football. I love professional football. When ESPN offered me college football, I respectfully declined because I’m a professional-football guy.

One of the things I’ve considered doing is forming a quarterback camp to teach young guys how to play the position, teach them about the leadership aspect of it, the preparation, the mechanics, the mental aspects.

Let’s return to ESPN. Do you know why the network let you go?

The meeting with those two executives only took about 15 minutes. First they said that I’d had a wonderful year. Our ratings were up 47 percent. I did everything I was asked to do, and they felt like it was my best year in broadcasting.

And then came the “but”—“But we really want to do something different with the show, we want to take it in a different direction, and we noticed that when the broadcast came back to you, you talked about football.” They want to make it more of an issue show and not a football show.

How did you respond?

It’s the first time I’d ever been fired. As I said before, in everything I’ve done in my life—whether it was my relationships, my marriages, my work—I have always made the decision to leave. This is the first time that someone had chosen something for me.

What did you do?

I remember walking out and calling Robin. She said, “Did we get a raise?” I said, “No, I got fired.” She thought I was joking. “No, I got fired.” It was like dead silence on the phone.

I was mad for about two months. I was angry because I felt like it was something I built—I was part of the foundation of NFL football on ESPN. And now I wasn’t a part of it anymore. Just like that.

When I broke my leg, I had the experience of being taken away from something I loved very much. So I reflected back on how I felt then. It took me three years to get over that. It took me about two months to rationalize how I was going to deal with getting fired.

What was that process?

Instead of getting mad and hating people, I found myself thinking about the great times and the lessons I’d learned. I just don’t believe in hate. If I can’t control it, there’s no sense in getting upset about it. The best thing for me to do was focus on what I could control, and that was my future. So I directed myself toward more positive things.

Are you angry with ESPN?

I love ESPN. I love everybody at ESPN. I have worked with some of the greatest people. Mike Patrick and Paul McGuire are some of my best friends. I’ve learned from every one of them. You’re never going to hear me say anything bad about ESPN.

Come on, Joe, they slammed you.

I feel like they did me wrong. I don’t like it, I was hurt by it, but I’ll tell you: My experiences with the people there were absolutely phenomenal. I have no regrets. We built the brand. I have the utmost respect and admiration for every person I’ve ever worked with there, including Tony.

How can you not be angry with Tony Kornheiser?

The way I looked at this, Tony and Jaws [Ron Jaworski] did a segment on Pardon the Interruption [an ESPN talk show with Kornheiser and his Washington Post colleague Michael Wilbon] last year. I think that the executives in the company liked the way that short segment looked. They told me they were replacing me because I talked about football. When I asked them who was going to replace me, they said Ronny. And I said, “Ron’s more anal about football than I am.” Ron and I are the same football guys. So I’m being replaced by myself.

But I think that the interaction that Tony and Ron had on PTI probably was the motivation for them to make the change.

People assume you and Kornheiser didn’t hit it off. True?

Not at all. What’s funny is that I worked my ass off to help Tony understand how to broadcast from a booth. From simple things like not having water bottles when they come to us on camera. I was the one who made sure he had his face cloth up there, that he kept it in front of him, helping him put his earpiece in.

How do you think Kornheiser’s doing?

I don’t know. But let’s be honest—it’s Tony’s show. The show is about Tony. But in the middle of last year, Tony was talking about leaving. I said, “You can’t go. We have a chance to do something special here. I don’t want you to leave.”

He’ll tell you that. I wanted Tony to be there. I wanted him to stay. He talked about only doing two years. He’s finding out how hard it is, being on the road. This has not been easy for him by any stretch. But this has become Tony’s show.

What was it like on the set with him?

Tony would script his entire opening. I don’t like to rehearse. I’m like—let’s sit down and go. Tony’s role was to be cute, to come up with unique statements and observations. Mine was to do football. That’s the way it was explained, and that’s the way it played out for us last year. When we had a guest in the booth, Tony would ask the questions. The problem is Jamie Foxx is a friend of mine. Charles Barkley is a friend of mine. So I would wind up getting into the conversation; they’d bring me in.

Kornheiser describes himself as a bit neurotic.

Tony is the most neurotic person I’ve ever known in my life. I mean, God bless Amy Shapiro, his assistant. She’s a saint. She makes sure he has his pretzel. She makes sure he has his face cloth. She makes sure he gets someplace on time. She handles all his scheduling. She’s marvelous at taking care of him. He doesn’t pay her enough. You can put that in big print—“Tony, you don’t pay Amy enough to put up with you.”

Did you really walk away with no hard feelings?

Like anything else, there’s a minor regret. I felt like toward the end of the year we had something going. We had started to develop a chemistry, a feel for one another. We could play off each other. And the regret is I didn’t get a chance to see how really good it could have been.

In a way, Monday Night Football has been your stage.

I played on Monday night, I was hurt on Monday night, I worked on Monday night, and I got fired from Monday night. So now, my life has come full circle.

Have you had any conversations with Tony?

We’ve talked a couple of times. I wished him a lot of luck and said I would miss him. When I got let go, I got calls from the commissioner of football, coaches, the people at ESPN, including the executives and the guys who fired me, players I’ve known, owners—everybody. The first was [Denver coach] Mike Shanahan saying, “What the heck happened?”

What did Tony say?

He thanked me for the time we spent together. He thanked me the most for helping him get into restaurants when he couldn’t get in. He says, “If you want to go out to dinner, you go out with Joe Theismann because there’s always a table available.” He thanked me for helping him.

Does that help you begin the next phase of your life?

In a way, the broadcast became a set of blinders for me. It was all I knew; it was all I did. My life was consumed with coaches and players, reading articles, studying film. Now I have 50 hours a week to myself that I didn’t have before.

How does that feel?

Think of me as a recovering broadcast addict. I’m going through withdrawal. I don’t know what I’m going to do next. I’m at a very interesting place in my life mentally.

What’s the hardest part for you?

Trying to make the right kind of decision for what I get into next. My days are full already. I manage my own investments. I’m traveling four and five days a week, giving speeches, signing footballs. It can be frenetic. Still, I wake up some days with no game plan. I can be very regimented. Now I’m not sure about how the days will unfold. I’m adjusting.

You seem to be adjusting pretty well.

I think of myself as the kid who’s lived dream after dream after dream. I’ve had three careers: one in football, one in broadcasting, and I still have one in speaking. I really feel like I can change people’s lives. I honestly believe that by having the time that I have with them, somebody in that room is going to think about something I said, and it will make a difference in their life. It gives me great impetus and passion.

Did getting fired teach you anything about yourself?

Sure. You never, ever want to find yourself working for the acknowledgment and satisfaction of someone else. When you do your job, you do it with a great amount of pride because you want to be the best. If your best is really good but not good enough for them, that doesn’t matter as long as you can look at yourself in the mirror and say, “I’m proud of my body of work. I’m proud of the opportunity I had, and I’m leaving it at that.” So for me, that’s the lesson I learned from this.

The good Lord closes a door and then he opens a door. I believe this very firmly. Sometimes you don’t know where that door will lead, but it’s sure worth walking through to find out. And I don’t know what’s out there.

And if you could play one sport now?

I would play golf every day if I could. Come to think of it, I do.

What’s your handicap?

One—most of the time.

Joe as a Three-Time Cover Boy

Joe Theismann has landed on the cover of The Washingtonian three times, always with a splash.

July 1978

The brash Theismann predicted—accurately—that he would topple Billy Kilmer in the coming season as the Redskins’ starting quarterback.

He posed shirtless and said, “My nickname is ‘Hollywood.’ And I don’t mind admitting I like doing things out of the ordinary. I like flashy cars—American makes. When I was in high school, I was the hit of the drive-ins—in a 1963 Rambler, until my dad got me a convertible. Even now, I’m the kind of guy who likes to rent a limousine when we go out on the town.”

He also admitted that he had problems keeping his ego in check: “My mouth has always preceded my performance.”

September 1984

A year after the Redskins’ first Super Bowl win and months after Theismann separated from wife Shari, she posed tearing up her husband’s 1978 cover.

“Success ruined our marriage,” she said. “Or perhaps Joe’s inability to handle that success. He lost his values.

“After he won the Super Bowl in ’83, he had all these speaking engagements and got a part in this new Burt Reynolds movie. If there was a place he could stick his name, he would do it.

“Joe likes the limelight. He likes the accolades, loves the applause, needs the audience.”

August 1987

His playing career over, Theismann talked about his first date with TV star Cathy Lee Crosby, his fractious relationship with coach Joe Gibbs, and the injury that ended his career.

“When I asked Joe Gibbs later why he never came by [the hospital after the broken leg], he said he had been busy that week getting ready for the next game.

“I said, ‘Okay, but what about the night it happened.’

“He said, ‘I was tired.’ Yeah. Right. I was a little tired myself that night.

“ ‘You could have stopped by sometime,’ I said. ‘You talk about how much I meant to this football team and you give me all your bullshit about caring about people, but when it comes down to brass tacks, you don’t even stop by.’

Joe said, ‘I’m really sorry. . . .’

“This game has so much beauty and so much pain. There are moments you wish you could preserve forever. Not many people ever experience such great highs. But then it’s over. It just ends. All is quiet, and all is dark.”

National editor Harry Jaffe writes the monthly Post Watch column. In September 2006, he profiled Redskins owner Dan Snyder.