Our intervention with my mother, Susan Mary Alsop, took place during duck-hunting season. I flew to Washington from Maine in late October 1995. Soon after arriving in Georgetown, a familiar alarm began to ring in my brain—one that sounded whenever I was about to see my mother.

Susan Mary acquired her surname from her second husband, newspaperman Joseph Alsop. Joe was a newspaper columnist who worked in Washington most of his life. For 30 years his column, Matter of Fact, appeared in nearly 300 papers around the country. She had divorced Joe more than 20 years earlier and moved back into a house her mother owned on 29th Street in Georgetown. It was a beige house that she livened up with bright colors and Louis XVI furniture.

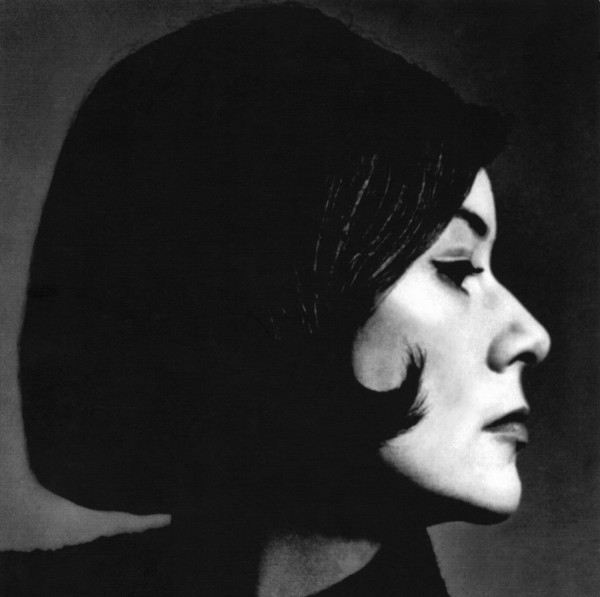

Mother was 77 in the fall of 1995. After leaving Joe, she had made a name for herself as an author and hostess. Leafing through Spade and Archer’s 50 Maps of Washington, DC several years ago, I found a section titled “Susan Mary Alsop’s Georgetown” with a map of one of her favorite walks. On another page she was included on a short list of the city’s “grande dames and power hostesses.”

Susan Mary drove a Honda and was generally frugal, so her elevated status had crept up on me. Perhaps I’d been living in Maine too long. During the past half century, she had established a reputation for her capacity to connect powerful people and for her discretion. I hadn’t realized how far her gift for maintaining emotional boundaries had catapulted her into stardom.

She combined an inner steeliness with the subdued elegance of a Jamesian—or perhaps Merchant/Ivory—heroine. As more than one reviewer observed about my mother’s historical biographies, she belonged in the stories she wrote. Power, diplomacy, and elegance were fused together in both her books and her life.

Mother had two address books—one for America, one for Europe. Reading through them, one sees the outline of her three “careers”—diplomat’s wife in Paris, journalist’s wife in Washington, and, toward the end of her life, successful writer. The names and addresses give credence to the assertion she once made that she wasn’t interested in living “an ordinary life.”

My mother’s stoicism was an asset in her world of artists and statesmen, intellectuals and diplomats. Her elegance was appreciated by most, less so by me. I thought of her as a brave little soldier and was always surprised when my friends told me how warm and engaging she had been with them. Her flair for attracting friends and offering her services to others was legendary. I think it was a survival skill—though she would have laughed politely at that idea and then dismissed it as pop psychology.

Until my stepfather, Joe Alsop, died in 1989, few of us had seriously worried about my mother’s drinking. Mostly our concerns focused on Joe’s. Although Joe and Susan Mary had divorced 15 years earlier and lived separately, they remained a pair. They went to parties together, went on walks together, and focused on their grandchildren together.

My mother had controlled her drinking for years, but after Joe’s death my younger sister, Anne, and I could sense her deep loneliness. When I sat down alone with my mother after lunch once and told her she needed help, she thanked me icily and left the room.

The intervention we planned had been triggered by my sister’s plan to relocate Mother to Salt Lake City, where Anne lived with her husband, John, and their two little girls. Most friends thought that uprooting my mother from Washington was a crazy idea but appreciated that Anne was taking some initiative.

In the early summer of 1995, Anne and John drove down the coast from our summer house in Northeast Harbor, Maine, with Mother to visit me in Camden. Her move to Utah seemed decided without much discussion. But when I visited her alone in Northeast Harbor later in the summer, I could tell she was terrified.

I had been pushing for an intervention for some time. Anne began to have doubts when she heard reports of Mother passing out in Northeast Harbor. As my sister began to realize how disturbing our mother’s alcoholism would be for her two little girls, we agreed to try an intervention.

Anne likes to say life is “whitewater”—a feeling that lay just below the surface of our upbringing. She once told a reporter that, growing up in Washington, we expected “the roof to come crashing down at any time.” We’re both so conditioned to the idea of Armageddon that I sometimes wonder if we don’t invite it.

We have an unusual aptitude for bilateral vision. When Anne and I are in a restaurant, we’re instinctively aware of the people around us; like camp survivors, we tend to be always on our toes, looking around corners. The center of the action always tends to be somewhere else; certainly it was never us.

In August 1995 I referred Anne to the Freedom Institute, a substance-abuse center in Manhattan. Anne called the director and liked her. She recruited three of my mother’s close friends to join us for the intervention.

When we arrived in Washington, Mother assumed we had come to divide up the furnishings of her Georgetown house, which was being readied for sale. I sensed that she had agreed to move to Utah in large part to please Anne. The evening before the intervention, Anne and I went through the downstairs dividing up furniture with yellow stickers.

When we were finished, my mother took us out to dinner at the Mayflower Hotel with some friends, a younger couple who were devoted to her. As I watched people drink their wine and martinis, I wondered how my mother would look at an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting.

The chain of love, as the group of interveners is sometimes called, gathered in a hotel room off Connecticut Avenue the following morning. Anne and I were joined by two strong women who were among my mother’s oldest friends: Nancy Pierrepont, a New York interior decorator who had helped Mother redo her Georgetown house, and Polly Fritchey, another Washington power hostess. Anne also had invited Charles Whitehouse, a retired career ambassador and a cousin of my mother’s. He represented the Foreign Service, my mother’s spiritual home.

The other half of our group was family: Anne’s husband, John, and my daughter Eliza. She had visited Mother that summer in Maine and, like Nancy Pierrepont, had seen her lying on the floor drunk and spent a long night helping the nurses watch over her.

The initial goal of an intervention is to persuade the alcoholic to accept treatment. What gave our group an edge in dealing with my mother was that her close friends were involved. They were breaking the cardinal WASP rule against talking about an embarrassing personal secret. The friends present were her real family. When it came to important decisions, my mother depended far more on friends than on family. The fact that both groups were united amounted to a palace coup.

Whatever qualms Mother’s friends may have had about AA, they had agreed to step forward and confront her. They did so because they were far more down to earth than she was and had no illusions about the seriousness of the situation. Behind the pinstripe suits and elegant clothes, they understood the perils of substance abuse and had seen the consequences of Susan Mary’s drinking. Like my mother, they were intensely loyal.

John escorted my mother to the hotel in a limousine on the pretext that she was needed for a family meeting. She walked into the room wearing a beige raincoat and Tyrolean hat. She looked dowdy in comparison to Connie Murray, the Freedom Institute counselor, who had a Park Avenue look.

It was impossible to gauge my mother’s reaction. Her manners camouflaged her real feelings. She sat down and waited with a benign smile to see what was going to happen next.

We had been told to use nonaccusatory language. Each of us expressed our love for her and then detailed examples of alcoholic behavior that caused us concern. “Love” is probably the wrong word for what we were expressing; in light of our controlled behavior, it was more devotion and loyalty. Either way, the counselor guided the conversation as we took turns telling our stories.

The most troubling instances were the most recent, particularly events that Eliza and others had witnessed at the end of the summer. One example involved Mrs. Pierrepont’s arranging for an ambulance to take my mother to the hospital after she had passed out on the floor of her house. Polly Fritchey had been visiting Northeast Harbor that August and had seen Susan Mary fall into the bushes after a cocktail party given by their friend Brooke Astor.

Anne and I were the last to speak. Anne was the only one to show her feelings with real passion. “Mummy,” she said, “I adore you, but I can’t put my daughters at risk by having you live next door if you’re going to keep up the smoking and drinking.”

Finally I spoke. I had been in encounter groups of this type before, but with my mother and sister both in the room I felt on uneven footing. It felt almost reassuring to notice that Mother was clearly not interested in what I was saying, and I can’t remember a word of what I said. I knew she realized that this gathering wasn’t about words; her mind was racing ahead to anticipate our agenda. The moment was simply another of the many dances we had done all of our lives. She was pretending to listen attentively, but her mind was calculating the best escape route.

After each of us had spoken, my mother asked in a puzzled tone what we wanted her to do about it. Connie Murray, the counselor, had the answer. She told my mother we had found a program, the Chemical Dependency Family Program at St. Mary’s Hospital, which had a good reputation for treating older people. Susan Mary was shocked to hear that the hospital was in Minnesota and that we had booked a flight for her that afternoon.

I was fairly sure my mother would accept our suggestion that she seek help—at least temporarily. We were too unified in our approach, and our language too direct, for her to dismiss us outright. She hated public scenes and was accustomed to using courtesy as a weapon to buy time on the rare occasions when she was cornered by circumstance. I also knew she couldn’t abide waiting around.

Although Mother expressed concern about outstanding commitments, such as an upcoming dinner party she was hosting, she didn’t belabor the point. It wasn’t in her nature to be ungrateful when special efforts were made on her behalf, and there was no way she could understand our intervention as anything but a special effort. She was momentarily trapped by her unforgiving code of manners.

The maids had my mother’s bags packed when we returned to 29th Street. Soon I was alone with her in a taxi headed for National Airport. She fumbled through her handbag checking for phone messages she might have missed that morning. She had several messages, including one from Yitzhak Rabin’s wife and one from Colin Powell’s wife.

As the taxi drove along the Potomac River, it struck me that my mother had never been to the American Midwest. The daughter of a diplomat, she was born in Rome and as a girl lived in Romania and Argentina. She had visited Europe’s cathedrals, walked around Vienna and St. Petersburg, danced under the chandeliers at Versailles, and floated down the Grand Canal to Venetian costume balls. She had dined privately with Presidents Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon. Yet she had never been to the heartland and had never eaten a Big Mac.

A tenet of Alcoholics Anonymous is that social status is irrelevant, an impediment to the honesty needed to address the pains and fears of alcoholism. Facing the disease takes a special courage, a willingness to expose your vulnerabilities rather than disguising them with sophistication and wit. My mother was courageous, but she always devoted her strength to covering up pain, not revealing it.

AA assumes we all share certain basic feelings, that we’re more alike than we are different. My mother’s life was predicated on an entirely different principle. She reveled in her uniqueness. On a certain level, she had a point. Susan Mary had not only outlived most of her contemporaries; she had also begun to blossom as an author of well-received biographies and architectural essays when many of her peers were preparing to retire. In 70 years, she had crafted a distinctive life in Paris and then in Washington. In her mind, she had done this essentially by herself. Her sense of uniqueness was well earned.

Using a veil of self-effacement and manners, she almost always got her way. She orchestrated everyone around her. She had a knack for making people believe she was fascinated by them even when she was itching for them to leave. She was intellectually redoubtable. She was also physically resilient, having conquered colon cancer and lived for more than half a century as a cigarette-smoking anorexic. So who was going to convince her that something as familiar as booze was stronger than she was?

Exile is a familiar experience for me. Beginning when I was nine, I was shipped off each year from Paris to Beachborough, an English boarding school outside Oxford. At 13, I was sent from Washington to Groton, a boarding school in Massachusetts, where I spent the next five years.

At age four, I had been sent from our house in Paris to a French school. I remember the first day well because I vomited in the classroom. That earned me a yearlong reprieve from school. In my experience, the void of being abandoned is registered most acutely in the stomach.

Now, on her way to Minnesota, it was my mother who was being exiled, and it was she who was having “tummy problems,” as she called them. She rose from her seat several times on the flight to go to the toilet. At one point, she leaned toward me and conceded, “I don’t think I’ve ever felt so depressed in my life.” A little later she promised, “Don’t worry—I’ll behave.”

Well into the flight I noticed Senator Paul Wellstone working the aisles on a trip back to his home state. I marveled at his energy but was relieved my mother didn’t recognize the disheveled liberal from Minnesota as he moved down the aisle fishing for eye contact. Unlike Colin Powell or Yitzhak Rabin, he had never made the guest list at 29th Street.

When we reached the hospital, it was late afternoon. I brought my mother up to the third floor, where the “seniors” stayed. The ward seemed calm, and I was pleased that Mother had a private room.

In our family, goodbyes are abrupt, and this was no exception. I left my mother and returned to Maine. I wrote her several letters, our customary way of communicating. My stepfather, Joe Alsop, had even proposed to my mother using airline stationery.

In one letter I tried to explain how we were trapped in our family by words, by our addiction to writing, by our tendency to intellectualize. Although I wrote, “The program seems so bloody simple that it almost demeans us,” I found myself employing the simplistic bromides of the rehabilitation program itself. I even resorted to clichés from my upbringing—phrases like “I’m so proud of you” and bloodless pronouncements like “You will, of course, make up your mind about the length of treatment after the evaluation is completed.”

I cringe when I read these letters. “Try to realize,” I wrote, “that whatever you do or say, you are and have been forever a real success in my eyes.” Why couldn’t I tell her that in some ways she was a success but that she had never been a good mother? Though I hoped I would somehow connect with her, I couldn’t divorce myself from the fear that this was still one more charade.

Before returning to St. Mary’s Hospital, Anne and I had a conference call with our mother and Kal, her counselor. Susan Mary explained coolly that she would be leaving the program early, as she had committed to hosting a dinner for Architectural Digest in Washington. Anne’s voice rose and faltered as she reminded Mother that she had promised to complete the program in order to move out to Utah.

“Oh, but I thought you knew,” my mother responded calmly. “I have no intention of moving to Utah.”

About ten days later, I flew to Minneapolis to join Anne and John in the Seniors Family Program, an opportunity to address the issues of alcoholism as a family.

When I saw my mother, one of the first things I noticed without surprise was how much she was trying to take care of the staff. She was constantly complimenting the counselors. Kal told us how impressed he was by my mother’s diplomatic skills.

On October 31, I headed for the hospital cafeteria, where I saw Fran, our family counselor, walking out with some people. As she passed, she gave me an unusual look. There was tenderness in her eyes and none of the detachment most counselors maintain. I was feeling raw from a verbal attack from Anne earlier that morning in our family counseling session, so this compassionate glance left me unnerved.

All of a sudden I realized that some kind of secret was being kept from me. The combination of my sister’s flare-up and Fran’s glance told me that there was something going on.

When Anne, John, and I reconvened at St. Mary’s with Kal and Fran after lunch, I told the group—looking mainly at my sister—that I was leaving on the next plane unless someone told me what was up. The counselors nodded, and without much discussion we retreated to another room, where my mother soon joined us.

The room was just big enough for our small group. Not looking at anyone in particular, my mother started by telling of Duff Cooper’s death in 1954.

Duff Cooper was a familiar name. I knew he was the only cabinet minister in Neville Chamberlain’s government to resign over the Munich Pact of 1938 and was the British ambassador to Paris after the war. I had also learned a decade before, by reading John Charmley’s biography of him, that Duff had had an affair with my mother, but I had never talked with her about it. I had read Duff’s biography of the French diplomat Charles Maurice de Talleyrand before even knowing of their affair. My main impression of Duff Cooper was as a quasi-literary figure.

Most of my mother’s recitation focused on Duff’s wife, Lady Diana Cooper. Mother explained how his body had been taken off the ship on which he had died and had been brought back to Paris. Lady Diana, she said, “was so brave.” She had asked my mother to accompany her on the special train that would be taking her husband’s body back to London and the service at Westminster Abbey.

I had no idea why Mother was talking about an event that had happened almost 50 years earlier. Perhaps she was going to make an esoteric connection with Duff’s legendary drinking problems?

After a while, Kal nudged my mother. She looked up as if suddenly remembering, placing her palm on her forehead, and said, “Oh, yes, of course, and he’s your father.”

Anne later confessed that Mother had shared the “big secret” with her several years earlier after they had had several drinks.

Images of my father—or the man I had always believed was my father, Bill Patten, an American diplomat who was my mother’s first husband—flashed through my mind, especially the moment when I heard he had died. My English headmaster at Beachborough, whom we called Froggy, had opened the door of my classroom in 1960 to tell me that my mother was waiting to see me. He led me through the front parlor of my prep school and into his sitting room. There I saw my mother and her friend Marina Sulzberger sitting on his sofa. I knew instantly why they were there.

Hearing now about my real father, I broke down in tears and without saying a word left the room. I walked the corridor with the image of Bill Patten broken into pieces. John joined me and put his arm over my shoulder. When we returned, I was still too shocked to say much.

The most obvious tension in the room when I returned was between my mother and Anne. My sister claims that I asked Mother why she hadn’t told me before and that she said something to the effect that I was “too pathetic.” My sister may be right, but I have no recollection of asking the question, and I don’t recall my mother saying those words.

I suppose it felt better to have a First Lord of the Admiralty as my dad rather than the milkman, but as I returned to my hotel room later, I began to feel very sad for Bill Patten and a little sad for myself.

Despite our entreaties, my mother decided to terminate her treatment early, declaring victory over us once again. At the end of the family weekend, the patients and their families in our group stood in a circle and said goodbye.

My mother and I never talked about St. Mary’s again. If I hadn’t kept a diary of the events leading up to the intervention, the whole experience might have faded like a surrealistic dream—my mother kidnapped and shipped to a distant planet. It wasn’t hard for her to convince herself and her Georgetown friends that it had all been an embarrassing mistake.

Some of her friends have told me she made light of the whole episode. What none of us, including her lawyer, knew until after she died nine years later is that she had signed a contract to sell her Georgetown house in anticipation of moving to Salt Lake City before we left for St. Mary’s. Fortunately, the real-estate broker found a way of nullifying the contract.

Within a couple of years, Mother had slipped out of the agreements she had made to sobriety at St. Mary’s. She may have controlled her drinking more carefully, but she continued to smoke and drink. What saddened me more than her drinking was the battered hope that I could ever really connect with her.

After the intervention, my mother decided she wanted to spend Christmas with me in Camden. This was unprecedented; voyaging to Maine in the dead of winter wasn’t something she did unless her summer house had been broken into.

I picked her up at the Portland airport, and on the way to Camden we stopped at a bakery for coffee. She told me she had brought me one of her last important pieces of jewelry, a lovely emerald-and-diamond brooch. There was a moment of panic when she couldn’t find it, but she returned from the ladies’ room with relief on her face. She had secured the brooch with a safety pin to her underwear.

My daughters and ex-wife rallied around and played cards with her in the kitchen. But there was no way of overcoming the penitential undertone of her presence. I couldn’t even keep her physically comfortable. With her thin frame, she was always cold. When I asked if she was comfortable, she would insist she was wonderfully warm, but she later sent me two electric heaters as a thank-you present.

My mother wasn’t drinking that Christmas, but she was clearly white-knuckling through the holidays and living for her cigarettes. On the Sunday before Christmas, we arrived at church too early, and she refused to sit and wait. The strain on her that week was palpable.

In my diary I tried to describe the feeling: “Is it my aloneness or my aloneness from her?” I thought of the vacant look in my mother’s eyes in a photo of her sitting with her legs across Duff’s lap at the Volpi Ball in Venice 40 years earlier. I wondered whether he had been able to fill some of that emptiness in her.

Loyal friends such as Marietta Tree’s brother, Sam Peabody, were faithful summer guests during the last decade of my mother’s life, but it wasn’t a happy time, and Mother was depressed about her lack of energy. Thanks to my sister, she received superb care from live-in nurses, who fed her, cleaned the house, and did their best to control the cigarettes and booze. One big fear we had was that she would set fire to her sheets, as she often smoked while lying in bed. Fortunately, the nurses slept in her room, attending to her every wish.

In August 1998, Anne wrote our mother a letter: “Mummy, we had a two-, almost three-year haven. You came back to yourself. Engaged, honest, funny, no-holds-barred fantastic Susan Mary. Now the disease has kicked in; the remission is over. We’re losing you again. . . . You shake when you pour your tea. You are lying about your drinking. . . . Mama, I know you hate being told this. You are uncomplaining. You have emphysema. You are brave and you are lonely.”

A sign to me of the effects of my mother’s drinking was some uncharacteristically critical remarks she let slip about Nancy Reagan. In the early 1990s she had been quoted as referring to the former First Lady as a superficial person. I remember her friends being a little shocked.

Anne and I had enlisted the help of a substance-abuse expert at Georgetown University Hospital. He visited my mother but was experienced enough to see that behind her good manners she wasn’t about to take a recovery program seriously. The following spring, Anne wrote her another letter:

“Do not kid yourself: Your drinking took you to Georgetown Hospital. You were in detox, Mum, not for flu but for having abused your body, lost your mind, not made sense, lost your bodily controls. Alcoholics lie. You lie about your not drinking, you lie about pills you take and don’t take. It’s part of the disease. . . . Stop feeling sorry for yourself. Get real! You are not the only one in the world with this disease. You can get help.”

It had been four years since our intervention, and though Mother now substituted wine for Scotch and vodka, she had been drinking and smoking for the last few years. She had clearly beaten all the averages, but with most of her close friends gone, she was very lonely.

She also was quietly coping with incipient blindness. Her cataract operations were complicated by glaucoma. Toward the end of her life, she was virtually blind in one eye and could read only with a magnifying glass. Her principal consolation was a constant diet of books on tape.

In her eighties, my mother started to slip into dementia. A new summer resident and recent friend of hers, Charles Butt, lent her his private jet to fly back and forth from Maine during her last few summers. By the summer of 2002, she was spending nearly all of her time in her bedroom that looked out over the ocean. She would spend most of her days listening to audio books and at times seemed unresponsive to visitors.

Occasionally she would let out short, high-pitched screams we could hear from another room. I noticed them more clearly in her Georgetown home. They didn’t come from physical pain. They sounded to me like a final release of anger, like the million pent-up complaints and sadnesses that she had suppressed for 80 years.

She held on for another two years. In the spring of 2003, her doctor recommended hospice care. During the last month of her life, in the summer of 2004, my sister and I and our families gathered once again at 29th Street in Georgetown. My mother’s doctor, a Carmelite nun, suggested we hold a service for her because all of her grandchildren were there. We stood around her bed with the nurses who had lit candles and read some prayers. Each of the grandchildren shared their feelings for her.

Not knowing how much longer Mother would linger, I returned to join my wife, Sydney, in our house in the Pyrenees. My mother battled gamely for two weeks, though she did mention the idea of suicide to her doctor. She stayed in her little bedroom on 29th Street.

Her doctor speculated half seriously that maybe my mother was hanging on with such tenacity because, as a polite hostess, she didn’t want to leave the party before all the guests had gone. She gently explained to Mother that it was all right to let go and move on to a more peaceful place. Anne was there for that talk and remembers that Mother looked up toward Anne and said, “Tell her to go away; she’s being a bloody bore.”

On the afternoon of August 18, 2004, my sister called me at our home in the Pyrenees and said, “I have good news.” Our mother’s little body had finally given up.

Earlier that day, Sydney had performed in a piano-and-flute concert in our house. When I introduced the performers to our guests, I had mentioned that my mother was close to death. I said I could feel her spirit hovering above us and perhaps coming home to France. After Anne called, I walked out into the garden and looked up at the stars. I felt that—at last—my mother was not so far away.

Have something to say about this article? Send your thoughts to editorial@washingtonian.com, and your comment could appear in our next issue.

This article appears in the July 2008 issue of Washingtonian. To see more articles in this issue, click here.