When Terrence Barnett proposed to her, Yolanda Baker admired the pretty ring, then said no. She wanted the father of her twins to be part of their lives but was afraid of Barnett’s behavior.

When he got angry, Barnett would erupt in violence. Police charged him with threatening Baker, assaulting her, and destroying her property. “This was a man who beat her,” says Robert Hines, Baker’s brother-in-law. “This is a man who broke her wrist and pulled her hair out.”

Baker told Barnett she wouldn’t marry him until he changed. But she wouldn’t leave him. “She said she had kids by him and she really wanted a family,” says Niola Hines, Baker’s sister.

Baker’s mother worried. “I’m so scared he is going to be the cause of your death,” she said one night in 1998 after Barnett smashed the windshield of her daughter’s car.

A year later—on August 1, 1999—Yolanda Baker vanished, leaving behind a trail of questions in a case that has stumped DC police.

Barnett quickly became the primary suspect because of his history of domestic violence against Baker, police said. He didn’t report that Baker had been missing for three days, and he offered different stories to police and her family about her whereabouts.

Police searched Baker and Barnett’s home on 44th Street in Northeast DC and found signs that blood stains had been cleaned up. When crime-scene investigators sprayed a blood-detecting chemical on the walls and floor, a trail of blood glowed bluish-green from the reaction.

“It lit up like a Christmas tree all over the bedroom floor, the walls,” Robert Hines says police told him. “They could tell that there was some real struggling going on, down the stairs to the living room area, on the wall, over some of the furniture.”

The blood trail led out the door to where Baker’s car had been parked, but the car was missing. Weeks later, her black sedan was found in an alley a few miles away. Police told Hines that the wheel well in the back of the car was “full of blood.”

But Baker’s body has not been found, and no one has been charged with her murder.

Baker, who was 35, left behind five-year-old twins, a boy and girl. Barnett, their father, is gone, leaving after a six-year relationship with Baker marred by abuse, arrests, and restraining orders. “He had such a rage in him,” says Hines. “It was a rage like a ball of fire.”

“Are We Any Less?”

Unlike the murder of 24-year-old intern Chandra Levy, most DC homicides never get headlines or news coverage.

DC police recently announced an arrest in Levy’s case. Ingmar “Chuckie” Guandique was charged with first-degree murder in March. The 27-year-old Salvadoran immigrant already is serving a ten-year sentence for assaulting two women in Rock Creek Park near where Levy’s body was discovered a year after her disappearance in 2001.

The case had been an embarrassment for DC police, who were criticized for focusing too much on Levy’s affair with former congressman Gary Condit.

Robert Hines says it was hard for his family to watch the media frenzy. “They pulled out everything. They got dogs, they got the Park Police involved,” he says. “It was hard to come home and turn on the TV and you hear about this massive manhunt searching here and there, and we’re going, ‘Are we any less?’ ”

Each year on the anniversary of her sister’s disappearance, Niola Hines and her husband have contacted the DC mayor, the DC police chief, the US Attorney’s office—anyone they could think of who might help reopen the case. The family believes the DC police botched the initial investigation, allowing leads to slip away and evidence to be destroyed.

After the couple appealed last year to Mayor Adrian Fenty’s office, Baker’s case was reopened as a missing-body homicide by the DC police’s Major Case/Cold Case Unit. The new investigation is part of a project to reexamine more than 3,700 unsolved DC homicides over the last four decades.

Television and the CSI Effect

Advances in DNA technology and new investigative techniques have helped crack some cases, but the 13 detectives in the DC cold-case unit face lots of obstacles, many caused by the department’s missteps. Old homicide files have been misplaced or destroyed. Thousands of items of evidence, including drugs and firearms, have been lost or stolen at the police-evidence warehouse.

Many cold cases hit dead ends, but there have been arrests of surprised defendants for murders that occurred years before. The work bears little resemblance to TV crime shows, where any murder, no matter how old or complex, can be solved in an hour. The shows have heightened the public’s expectations so much that police call it the “CSI effect,” says Lieutenant Michael Farish, who leads DC’s homicide division.

“They think we can turn on special machines and we have all the answers,” he says. “It doesn’t work that way in real life. There are two hard things to tell families—one is that their loved one has been killed, and the other is the case is at a dead end.”

Barnett, who is still a suspect in Baker’s case, stuck to his story that he didn’t know what happened to Baker when detectives questioned him recently and wouldn’t say anything else, says Sergeant James Young of the cold-case unit. But Young believes the case will be solved.

“I think we’ll get it,” he says. “Every family wants closure, and we want these cases closed just as much as they do.”

Following Cold Trails

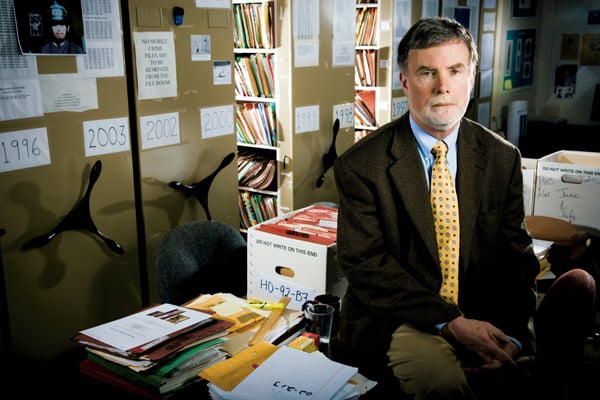

Detective Jim Trainum’s office at DC police headquarters is a warren of file cabinets and stacks of thick binders. A poster from the HBO crime series The Wire—“the most realistic cop show out there,” Trainum says—and a diagram of a semiautomatic pistol adorn the walls along with a white board listing the status of cases.

Trainum, 54 years old with salt-and-pepper hair, has served as a homicide detective, a member of a special team targeting repeat offenders, and a uniformed patrol officer. In the late 1980s, he went undercover for months, posing as a heroin junkie and burglar to get inside a fencing ring operating out of the Florida Avenue Grill in Northwest DC. Tacked to a bulletin board in his office is a photo of him from that time. Wearing large sunglasses and a beret, he’s carrying a “stolen” stereo receiver. Trainum would blow his nose on his clothes and smudge ink from newspapers onto his face. “I was a very convincing junkie,” he says.

As director of the cold-case unit’s Violent Crime Case Review Project, Trainum doesn’t hit the street much anymore. Over the past six years, he and a cadre of interns have reviewed almost 2,000 cold cases, creating a “solvability chart” for each. “We basically developed a sweatshop here where we are doing homicide case reviews,” he says.

They enter the details of each homicide—the names of any suspects and witnesses, potential DNA material, fingerprint and firearm evidence, and possible links to other crimes—into a computer database. Almost 300 homicides have been identified so far as having potential leads.

While some young officers try to hopscotch to the homicide unit as quickly as possible, Trainum says his decade of investigating burglaries, rapes, and other crimes before he became a homicide detective has helped him review cold cases.

“A detective has to understand the dynamics of rape to investigate the murder of a rape victim,” he says. If a husband kills his wife and then tries to cover his tracks by staging a burglary, a detective must know whether the scene looks like a true burglary.

Before joining the homicide unit in 1993, Trainum helped solve his first homicide by connecting a burglar who had a history of violence to the murder of a young woman who had been beaten and sodomized in a Capitol Hill alley.

“My experience is you don’t investigate the murder,” he says. “You investigate the crime that led up to the murder.” In the case of Yolanda Baker, the crimes that preceded her death stretched back for years.

“Have You Seen Her?”

The missing-person fliers that Baker’s family posted after her disappearance show an attractive African-American woman with a wide smile and a short bob. “Have You Seen Her?” the poster asked before listing the descriptions that police use: 35 years old, five-foot-nine, 160 pounds, medium-brown complexion, with a rose tattoo on her left ankle.

The poster didn’t say anything about Baker’s life. Born in 1964, she was called Princess by her family. She was the seventh of eight children of Elmer and Audrey Baker. “She was like our beauty baby, and that’s why we called her Princess,” Hines says of her younger sister. “She was so lovable.”

The brood grew up in a working-class neighborhood in Southeast DC before moving to Capitol Hill. Their father, a chef at Walter Reed Army Medical Center, and their mother, a no-nonsense homemaker, sent their children to Holy Comforter–Saint Cyprian Catholic school. “Those were the times when your neighbors saw you doing something and they told your mom or dad and you got it,” Niola Hines says. “We walked the chalk line. My mom was a very strict mom.”

After graduating from McKinley Technical High School, Baker held various jobs before becoming an acute-care technician at Washington Hospital Center. She raised a nephew for several years after another sister couldn’t care for the child. She was known for her generosity, love of good food, and funky dancing style. As friends cheered her on, she would shout “Owww!” and groove across the dance floor.

Then she met Terrence Barnett, a lanky man who worked in a government printing office and had two sons from a previous relationship. For a time, things went well. Baker then found out she was pregnant, not with one child but with two.

Her sister recalls, “She cried and said, ‘What am I going to do with two babies? I don’t even know how to raise one.’ ”

With family support, Baker saw the twins as a blessing. But Barnett’s mood darkened—the beginning of a long path of controlling behavior, jealousy, and unpredictable rage, Baker’s family says.

Amid the violence, Baker wavered, unsure what to do. She called the police and filed restraining orders to keep Barnett away, but she also let him move back into their home in the months before she disappeared.

Barnett was charged with assault in 1997 and with destruction of property in 1999 in two misdemeanor cases categorized as domestic violence by DC Superior Court; he also had been charged with assault in 1994. But prosecutors dismissed the charges each time, according to court records. In 1998, he was arrested on two more domestic-violence charges for assault and making threats. He pleaded guilty and was sentenced to 180 days in jail, but a judge at DC Superior Court agreed to suspend 135 days of the jail time if Barnett completed a year of probation without any incidents.

Barnett would end up back in jail after Baker’s disappearance, but not on a murder charge.

Dancing and Door Prizes

On July 31, 1999, Baker and Barnett went to a college fundraiser organized by Niola and Robert Hines for one of their two sons. The Saturday-night party wound into the early-morning hours with dancing, door prizes, and raffles at a parish hall in Suitland. It would be the last time Niola Hines would see her sister.

Over the next three days, Hines and another sister called Barnett, asking where Baker was because they hadn’t heard from her. He first said she had gone to the store and later said he hadn’t seen her since the party. He left their two children at a friend’s house, Hines says.

When Baker failed to show up at work, her family called the police. Because of his history of abuse, detectives questioned Barnett at the couple’s home, but he said he didn’t know where Yolanda was. He pointed to a broken window and said there had been a burglary, but he hadn’t called police.

Barnett was subject to a restraining order even though he had moved back into the home, so he returned to jail for more than four months for violating probation from his prior domestic-abuse conviction.

After Baker’s car was found, it was towed to an impoundment lot, but it was left outside in rain and snow that flooded the trunk, making it impossible to prove whether enough blood had been spilled to cause death, says Sergeant Young of the cold-case unit. Because of the missing body, that evidence was critical to proving that a murder had occurred.

The DNA in the blood from the trunk wasn’t destroyed, but police didn’t have a known sample of Baker’s DNA. Detectives used a blood sample from one of her sisters for a DNA test to confirm that the blood in the trunk was Baker’s, says Young, who took over the murder investigation after Trainum’s team identified it for review.

The main stumbling block in the initial investigation was Baker’s missing body. At the time, DC police rarely filed murder charges if the body couldn’t be found because it was hard to prove that the missing person was dead. After some successful prosecutions, DC police and the US Attorney’s office are now more aggressive in prosecuting homicides with missing bodies.

If Baker’s body is found, skin cells under her fingernails could provide possible DNA evidence from the killer. The remains also could show whether there was a struggle and whether she was strangled, stabbed, or shot. “Finding the remains is key,” Young says, “because the remains will possibly tell you a story about what happened.”

Police can’t force Barnett to give a DNA sample without a search warrant, Young adds, and the case is still under investigation. Barnett has moved away from DC and couldn’t be reached for comment.

When he was questioned recently, all Barnett would say is that he hadn’t seen Baker since the night she disappeared.

Some Lost, Some Stolen

Even though there’s no statute of limitations for murder, many DC homicide files have vanished. Most of the files from the 1960s have disappeared, the 1970s files are hit or miss, and the 1980s files are only slightly better, Trainum says.

“We were destroying evidence. We were stripping case files. We were making cases unprosecutable ten years after the crime,” he says. Many files were destroyed by employees who “were just not thinking ahead.” Under a new law approved by the DC Council, all open homicide files now must be kept for 65 years.

The storage of evidence at the police-evidence warehouse—a former furniture warehouse in Southeast DC—has posed more hurdles. The warehouse uses an outdated computer-inventory system that isn’t backed up and is prone to crashes. For many years, index cards were used to catalog evidence from thousands of cases. “It’s like your grandmother’s attic,” Trainum says. “We have no idea what we have over there, especially with older evidence.”

In 2008, the DC Inspector General’s Office published a long list of problems, including a leaking roof, an insecure drug-evidence vault made from plywood, and a lack of heating or air conditioning that allowed DNA evidence to deteriorate in extreme temperatures. Boxes were piled so high that evidence near the floor was crushed, with unknown fluids leaking onto the concrete floor.

Out of more than a million pieces of evidence stored in the warehouse, inspectors randomly selected 120—including drugs, firearms, and cash—that should have been there. More than a third of the 120 items had vanished, among them $16,453, eight handguns, a shotgun, and drugs including cocaine, amphetamines, and marijuana. Warehouse officials told inspectors they didn’t know if the evidence had been lost, destroyed, or stolen. The city broke ground on a new $20-million warehouse in May. It will have computer coding of all evidence and refrigerated DNA storage.

Even high-profile cases haven’t been immune to the problems. DC police lost the entire case file from the “freeway phantom” murders, the most notorious unsolved serial-killer case in DC history. In 1971 and 1972, six African-American girls were kidnapped and strangled before their bodies were dumped near freeways in DC and Maryland. The killer still hasn’t been caught, despite a $150,000 reward, and none of the evidence from the murders can be found at the evidence warehouse.

“Maybe it’s over there in some box and we haven’t stumbled across it,” Trainum says. “Who knows?”

Instead of giving up on the case, Trainum and his interns have rebuilt the freeway-phantom files, which now fill a long row of three-ring binders on a shelf in his office. He gathered information from retired DC detectives, the FBI, and police in Prince George’s County, where the last victim’s body was found.

Fluid believed to be semen was found on the last victim’s clothes, evidence that might identify the killer. But a DNA test is on hold, along with DNA tests in most cold cases, because DC police rely on the FBI’s overworked DNA lab in Quantico.

“We’ve been sitting on a lot of stuff,” Trainum says.

For current criminal cases in the District, it takes about nine months to get DNA test results from the FBI lab. Cold cases are at the back of the line. The backlog should be cleared after the DC police department opens its own lab in Southwest, part of a $218-million project with a mix of District and federal funding. Plans are under way for a six-floor building at Fourth and E streets, Southwest, to house the new forensic lab, a public-health lab, and expanded facilities for the medical examiner’s office. Crime-scene investigators and firearms and fingerprint units also will move into the building so evidence can be examined and tested in one place, reducing the risk of loss or contamination, says lab director William Vosburgh.

Meanwhile, some DNA samples are being sent to a private lab for testing. “It’s not like every case has a treasure trove of evidence,” Vosburgh says. “A lot of cases don’t. It’s one of those things where you never know what you have until you try it.”

Baker cried when she learned she was having twins, but she came to see them as a blessing. The children were five when she disappeared; now they’re in high school. Family photo courtesy of Robert Hines.

Surprising a Murderer

One of the cold-case unit’s first DNA hits led to the 2006 arrest of Melvin Jackson Jr., the 56-year-old deacon of a storefront church on Trinidad Avenue, Northeast. He’s awaiting trial on a first-degree murder charge for killing Raymonde Plantiveau 25 years ago.

Plantiveau, a 57-year-old French woman, was visiting her daughter in 1983 when she was attacked and stabbed to death during the burglary of a home on 39th Street, Northwest, just north of Georgetown University. After reopening the case and searching through the evidence warehouse, detectives found semen from a rape kit taken after Plantiveau’s death. It took more than a year to get the DNA results back from the FBI lab.

The DNA results were entered into an FBI-run database called the Combined DNA Index System, or CODIS. DNA samples, usually in the form of saliva on a cotton swab, are taken from offenders across the country after they’re convicted for certain violent crimes. If an offender is released and later commits a crime where DNA evidence is found, it often can be linked back to him through the national database. In Jackson’s case, a DNA sample taken after a 1970s robbery conviction in Virginia matched the DNA evidence from Plantiveau’s killing.

“It was a brand-new experience for us,” Trainum says.

In 2007, the cold-case unit made another DNA match from a botched heist a decade earlier at the DC Teachers Federal Credit Union on D Street, Northeast. A robber had shot and killed security guard Thurman Brown during a struggle but left his baseball cap at the scene. A DNA sample from the cap led to a murder charge against 53-year-old John Williams, an ex-convict who had served time for armed robbery and other crimes. He’s still awaiting trial.

Police departments in the suburbs have fewer cold cases to investigate, but they also have had successes with DNA hits. In May, the Prince George’s County Police Department charged 32-year-old Matthew Lamar Bethea of Glenarden with first-degree murder in the killing of 14-year-old Nia Aisha Owens, who was last seen walking to Northwestern High School in Hyattsville in 1996. Her body was found in woods near the school, and police say Bethea was linked to the slaying by DNA evidence.

The Montgomery County Police Department announced last year that detectives had solved the 1982 slaying of 20-year-old Wendy Lou Stark, a University of Maryland student kidnapped outside the Hillandale Shopping Center. She was sexually assaulted at an unknown location and shot several times after she escaped from her attacker’s car in a neighborhood just north of Kensington.

After locating the misplaced evidence and conducting DNA tests, police reported that they had linked the killing to Gerald Anderson Abernathy, an escaped inmate who had been hiding out in the area at the time of the killing. Abernathy died in 2007 from lung cancer while serving a life sentence for kidnapping and murder in North Carolina.

In 2005, police in Northern Virginia used DNA tests to link Alfredo R. Prieto to the rape and murder of a 22-year-old woman who had been shot with her boyfriend in a vacant lot near Reston in 1988. Prieto, who is on death row in California for the rape and murder of a 15-year-old girl, received two more death sentences last year for the Fairfax County slayings.

Prieto, 43, also was charged for the 1988 rape and murder of a 24-year-old woman behind McKinley Elementary School in Arlington. Prosecutors decided not to try him because he already is facing three death sentences.

“I Miss You Holding Me”

Baker’s family held a memorial service after her disappearance when it became obvious she had been killed. Her twin son and daughter wrote notes to their mother in the large-print letters of small children. “Dear Mom I love you,” her son wrote. “You were The Best Mom and I miss you. I miss you playing with me. I miss you holding me.”

The twins, who are now 15-year-old honor-roll students, are being raised by one of Baker’s sisters in the Washington area after the family won a custody fight with Barnett. “It’s still painful,” Niola Hines says. “Even though they are teenagers, you can see it in them. We do what we can do and we do the best we can, but it’s not the same.”

Hines hasn’t given up hope that her sister’s body will be found and her killer brought to justice.

“I pray on it every day,” she says. “It’s something that stays with you. It never leaves you.”

On June 23, one day before this story appeared in print, DC police arrested Barnett and charged him with second-degree murder in the ten-year-old case. Read more about it, here.

This article first appeared in the July 2009 issue of The Washingtonian. For more articles from that issue, click here.