>> To see all of Washingtonian's Top Lawyers, click here.

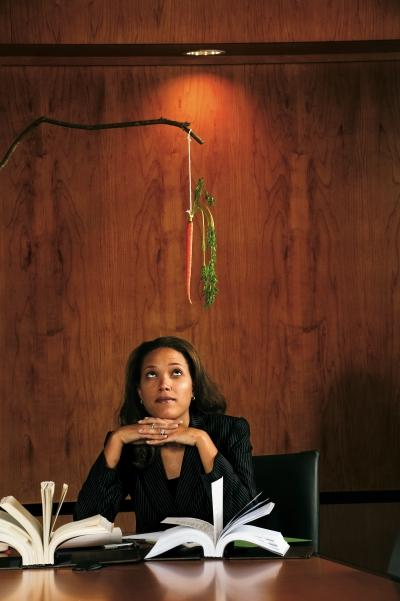

Jonice Gray Tucker sits in the Fairmont hotel’s courtyard. She’s not far from the law firm next door where she recently made partner. Dressed in a camel-colored pantsuit with her hair pulled off her makeup-free face, she’s calm and confident as she talks about her career.

Life is good in this serene spot, tucked away in the District’s prosperous West End, but getting here wasn’t easy.

The Washington native graduated from Yale Law in 2000, landed a clerkship on Maryland’s federal court, and joined Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom—the highest-grossing and maybe hardest-working law firm in the country—as an associate in 2001. She has billed tens of thousands of hours to clients, no doubt hundreds of which she would have rather spent with her two small children. Yet Tucker doesn’t hesitate when asked why making partner was worth the toil.

“To be a part of the decision-making process—not just from a standpoint of case strategy, client contact, and that sort of thing but from a policymaking standpoint internally—mattered to me.”

In other words, Tucker wants to operate like an owner of her firm. It’s the answer that partners across the region tend to give when they’re asked the same question.

Their responses begin to vary when they describe how a lawyer actually goes about making partner in an increasingly competitive business. Making partner is no longer a matter of sacrificing any semblance of a social life to grind through grunt work for seven or eight years. It takes strategy, self-promotion, connections, and—maybe most important during a year when several established law firms dissolved—luck.

Today there’s no simple formula for making partner, or remaining one. And for a bunch of über-competitive young lawyers with Ivy League diplomas on their walls, it can be frightening.

Tucker herself didn’t follow a traditional path. Sure, she spent the requisite eight years as an associate at a major law firm, though that’s not where she practices today. Rather than wait around for her number to come up at Skadden—which made just eight new partners in 2009, compared with 25 in 2008—Tucker left in March to follow partners Andrew Sandler and Benjamin Klubes to the 66-lawyer, DC-based financial-services law firm BuckleySandler. It’s a different world from Skadden, which has nearly 2,000 lawyers across 24 offices. At the new firm, Tucker became a partner.

“It did become important to me to have some prospect of advancing on what I consider to be a reasonable schedule,” says Tucker, who declines to speak specifically about her experience at Skadden. “I felt like it would be a much longer path at a significantly larger law firm.”

Skadden declined to comment for this story, though it’s by no means the only firm with a partnership that appears to be growing more exclusive. Several of Washington’s top-grossing firms slashed the sizes of their new-partner classes this year.

There is, of course, a fate worse than being denied entrance to the partnership: “We get calls pretty much on a daily basis from associates with elite credentials who would otherwise be very well situated to make partner at their firm,” says Washington legal recruiter Abe Pollack. “Now these folks are fighting just to maintain their job security.”

Thousands of lawyers, including many who thought they were on the track to partnership, lost that fight as firms cut people to survive the financial downturn.

One lawyer, in his eighth year of practice when he was laid off by a large DC law office, says he felt he had “a good path” going forward: “I’ve always felt like there are two different people who make partner, one being the rainmaker, the other being the worker bee, the good client-service partner. I was always shooting for that second guy.”

Yet the lawyer, who spoke on condition of anonymity, says there wasn’t enough work at his former firm even to feed the partners overseeing him. Consequently, the client matters on his desk were shuffled off to more senior lawyers, making him expendable.

He has since landed at a smaller firm, where he remains an associate. He says making partner is no longer a goal. The lawyer is precisely the kind Pollack is talking about when he says, “A number of folks will miss their window. That’s the reality.”

When the Music Stopped

The unfortunate souls who will never make partner are victims of the excess that has infiltrated large firms. Salaries shot up during the past decade. In 2007, a booming year for legal business, first-year-associate salaries across major New York and Washington law firms jumped from $135,000 to $160,000. Williams & Connolly, Washington’s preeminent litigation firm, took it a step further, raising first-year compensation to $180,000.

Hourly billing rates followed suit, and partners at elite firms reaped the benefits. In 2007, New York’s Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen, & Katz posted average profits per partner of $4.9 million, according to the American Lawyer’s annual ranking of the highest-earning law firms. Skadden had the highest profits per partner in Washington in 2007, with the average partner in its office here taking home $2.28 million that year, according to Legal Times.

It was a grand time while it lasted.

Last year marked the end of the gold rush. Profits across Washington’s biggest firms stagnated, while New York firms saw their earnings go down. Wachtell’s partners took home nearly 20 percent less than they did the prior year.

The old pyramid structure of large law firms—with hundreds of associates billing thousands of hours at steep rates to support high partner-level profits—works well in boom years, but it falls apart in a downturn, say legal recruiters and consultants. Clients cut legal costs, and firms can’t sustain the overhead of paying all of those previously profitable worker bees.

That leads to layoffs as well as reluctance to make new partners. If the profit pool is drying up, why would existing partners choose to dilute their shares even further by welcoming new members into the club?

Getting away from that model is one of the reasons Andrew Sandler—the former Skadden partner who convinced Tucker and 11 other lawyers to follow him to BuckleySandler—says he decided to take his practice elsewhere. (Sandler became one half of BuckleySandler last spring when his group of Skadden litigators merged with the DC-based financial regulatory and transactional law firm Buckley Kolar.)

Seated next to Tucker on the Fairmont’s patio, Sandler says that at the smaller firm, a lawyer who demonstrates the ability to manage sophisticated cases and gain the confidence of clients can earn the title of partner. But Sandler hasn’t completely lost touch with his big-firm roots. To become a highly compensated partner, he says, a lawyer needs to create new business.

Sandler feels he has much more flexibility to promote lawyers in a small-firm environment, even if they don’t all get to bring home a million dollars a year.

“If I’m going to ask young lawyers to make the kind of sacrifices they need to make to develop the skill sets and service the clients, I have to be able to look them in the eye and say, ‘If you perform, you’re going to be a partner,’ ” he says. “I felt it was important to operate in a business model where I could do that.”

Wanted: Emotional Intelligence

Behind the glass exteriors of trophy office buildings across downtown DC, thousands of lawyers are still plugging away in the big-firm model, hoping for a corner office and a piece of the profits.

Recently promoted WilmerHale partner Tonya Robinson is one of the elite few who succeeded this year. Listening to her describe her recipe for making partner at Wilmer—the second-highest-grossing firm in the District—is a lot like listening to the overachieving senior-class president tick off the list of extracurricular activities that got her into her first-choice college.

“It’s important to do high-quality legal work, for sure,” says Robinson, a commercial litigator in the firm’s Washington office. “But I don’t think it’s enough. You have to think strategically about how to build your profile.”

Robinson says she worked hard to mentor younger lawyers and look for opportunities that would make her “more visible” to firm management. That entailed serving on pro bono, diversity, and community-service committees.

She also emphasizes the value of great references: “I had partners who were willing to brag about the good work I was doing for them.”

Robinson stands out in other ways. In addition to practicing for nearly seven years at Wilmer, she did a three-year stint advising then-senator Joe Biden as counsel to the Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Crime. At a Washington-based firm like Wilmer—which is home to past government legal stars such as former solicitor general Seth Waxman and former deputy attorney general Jamie Gorelick—high-profile political experience can be an invaluable item on a young lawyer’s résumé.

Wilmer’s co-managing partner William Perlstein made partner at the firm in 1982. He did it the old-fashioned way, starting at the firm as an associate and working his way up over 7½ years. The criterion, he says, has evolved: “It is certainly a broader set of skills. It is certainly not enough simply to be a very good lawyer.”

Perlstein says the firm now factors in what he calls emotional intelligence. To him, that includes well-developed interpersonal skills and an ability to manage large teams working on client matters.

The logistics of making partner have also changed as Wilmer has grown to more than 1,000 lawyers. It now takes 8½ to 11½ years to be considered for partner. Each summer, a 32-partner committee starts collecting evaluations of possible candidates. The committee works closely with the firm’s entire 320-member partnership to solicit views on every candidate. Before the new year, the decision is put to a full vote of the partnership.

Wilmer’s process is similar to that of other large firms. It bears almost no resemblance to the fraternal way lawyers of Perlstein’s generation were welcomed into the club. Perlstein says his fate was decided in the early ’80s by the existing partners as they mulled over their options on a Saturday afternoon.

This year, Wilmer named ten new partners, down from 23 in 2008.

Partnership or Bust

All of that uncertainty and unease is good for business in another sector: the mental-health industry. According to the American Psychiatric Association, 19 percent of lawyers experience depression, compared with 7 percent of the general population.

Washington’s legal community got a reminder of how serious this issue can be when Mark Levy, the 59-year-old head of Kilpatrick Stockton’s Supreme Court practice, shot himself last April in his 11th-floor office. Levy, who was a counsel in the Atlanta-based firm’s Washington office, had been laid off two days earlier.

He was one of more than 5,000 lawyers let go from major law firms since January 2008, according to the Web site Law Shucks, which tracks legal layoffs. Many lawyers still lucky enough to have their jobs have been affected by salary freezes or pay reductions.

With the profession shell-shocked from those cutbacks as well as entire law-firm dissolutions, anecdotal evidence indicates that lawyers are only getting gloomier. The American Bar Association invited a psychiatrist to speak about depression at its annual meeting in Chicago. And more than half of respondents to a recent poll conducted by the blog Above the Law said they suffer from depression, anxiety, or another mental illness. A third said they struggle with sleep problems and chronic fatigue.

Why stay in such a profession? The money can be great, but mental-health professionals say the reasons go beyond that.

Paul Appelbaum, a professor of psychiatry at Columbia University, treats lawyers. He says many young lawyers’ identities have become so bound up in their achievements that their self-image becomes dependent on always being able to make their next goal. “For the ones who do, that is often very satisfying,” Appelbaum says. “For the ones who fail to, that can be an enormous blow to their self-esteem—and one that leaves them anxious, depressed, and uncertain where they go next in life.”

Washington psychologist Renana Brooks echoes that perspective. She says more lawyers are seeking her help after being laid off or not making partner. The disappointment, she says, “is enough to send them to the mental institution.” She’s not joking: “What it takes to be a partner is a singular focus on doing anything at all costs to succeed.” If that doesn’t work out, Brooks says, lawyers can lose their entire identity.

Ask any lawyer to recall the moment he or she first made partner and the import of that milestone is evident.

Jennifer Trock, one of the newest partners in the Washington office of Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman, was out of town meeting with clients the week she expected to find out whether she had made partner.

“I intentionally left my phone on,” she says. “I was staring at it every five minutes.” But the call never came.

It was only after Trock returned to the office the following week that she got the news. Her practice group’s head partner called her into his office and put her on the phone with the firm chairman. Then out came the Champagne.

The memory still eliciting a big smile, Trock says: “They timed it so everyone on the floor could come by and do a toast.”

Congratulations! Now Work Harder

Eventually, that happy moment fades and the reality of actually being a partner sets in. There was a time, 10 or 15 years ago, when making partner was akin to getting tenure. The traditional compensation model for partners worked in lockstep, with partners automatically getting a larger share of the firm profits each year. A senior partner could play a round of golf in the middle of the week and still sleep soundly.

With a few exceptions, that system is now extinct.

“One of the things that probably no law firm talks to associates about enough is the idea that partner is not a reward for being a good associate,” says O’Melveny & Myers’s Washington managing partner Brian Brooks. “Partner is just a different job.”

Like nearly all large firms today, O’Melveny compensates its partners based on performance. Says Brooks: “Partners who have a very unproductive year will fall in [profit] shares—and I suppose, in theory, could fall in shares enough that they might decide, you know, that staying here wasn’t the right career move for them.”

Brooks says O’Melveny doesn’t have a history of laying off partners, but in general, lawyers and legal-industry experts say underperforming partners are no longer immune from getting pink-slipped.

Firing partners is a much more delicate procedure than letting dozens of associates go in one fell swoop. Partners are asked to leave quietly, say the legal recruiters who are retained to place them at new firms.

Susan Manch, a Washington consultant who specializes in lawyer outplacement, says partnership agreements typically mandate a full vote of the partnership to force a partner out. However, she says most of the fired partners she works with didn’t invoke that provision; they knew it wouldn’t save them. Firm management, after all, wouldn’t have asked them to leave without first securing the support of the other partners.

Manch says getting fired as a partner is worse than getting laid off as an associate. Partners have typically had the chance to build more attractive résumés and client bases, but they’ve also likely spent years building a lifestyle that’s unsustainable once they’re out of work. Manch says getting let go hurts a lot more for partners who have million-dollar homes, kids in private school, and spouses who don’t work than for associates who have just leased a BMW.

Part of the problem for new partners is that suddenly they’re expected to generate business in a way that wasn’t required when they were associates. If they don’t figure it out, all bets are off on their job security.

Manch notes that some firms have begun training programs to help associates sharpen their business-development skills before they’re up for promotion to partner. But for the most part, she says, “people are made partner and they’re just sort of thrown to the wolves.”

If only law schools taught wilderness survival.