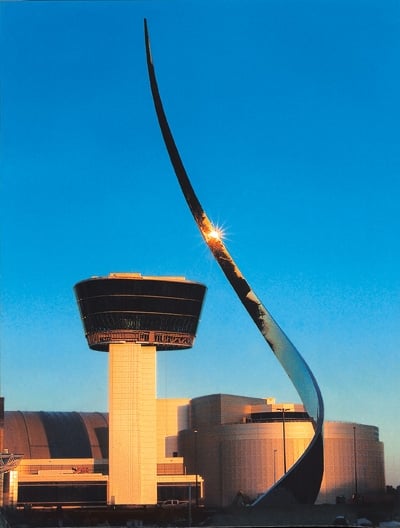

His sculpture “Ascent”—a soaring, polished-steel salute to aerospace—greets some 3 million visitors a year at the entrance of the National Air and Space Museum’s Udvar-Hazy Center near Dulles Airport. “Limits of Infinity” presides over George Washington University’s rose garden, and “Golden Quill” greets visitors to its library. “Serve” adorns Rock Creek Park Tennis Center, as “Symbol of Courage” does Georgetown University’s Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center.

His “Timepiece,” which hung in downtown DC’s International Square for years but disappeared when the lobby was renovated, held the Guinness World Records title as the world’s largest clock. It kept time within a hundredth of a second and indicated when the sun was directly overhead in 12 world cities.

Other works by the sculptor grace US embassies abroad as well as the United Nations Headquarters in New York City and can be found in more than 1,000 private collections. The New York Times has noted that “the best-known works of art shown abroad” by the US State Department include “the photography of Ansel Adams, the paintings of Georgia O’Keeffe, and the sculpture of John Safer.”

C. Douglas Lewis, former curator of sculpture for the National Gallery of Art, called John Safer “a visionary genius whose works in fields as diverse as aerospace, Shakespeare, sports, engineering, and antiquity are rich with a sense of exploration and experiment, yet each remains instantly identifiable as a work of John Safer. He captures what is essential and reduces it to the pure line in space that Aristotle believed to be the basis of sculpture.”

But Safer remains unknown to most of his fellow Washingtonians. Over the course of his eight decades, he has been a real-estate developer; chairman of what was then Financial General Bankshares; chairman of DC NationsBank, which became part of Bank of America; and chairman of Materia, a plastics company.

It’s largely because of Safer’s fundraising efforts that Rock Creek Park Tennis Center exists, and he played a significant role in the Udvar-Hazy Center’s development. He survived World War II as a pilot and was Eugene McCarthy’s campaign manager, but it’s his evocative works of metallurgical poetry that prompt some to call him one of America’s greatest sculptors.

John Safer was born and raised in the District, the only child of John and Rebecca Safer. His father, a Georgetown-educated lawyer, operated a moving-and-storage business. His mother was a social activist, suffragette, and intellectual who had John reading and writing by age four, when she enrolled him in first grade at what was then Maret French School (now Maret School).

Fluent in French, Safer graduated from DC’s Woodrow Wilson High School at age 14. His mother wanted him to go to Harvard, but John felt that his youth and small stature would make him uncomfortable there. So he deliberately flunked his Harvard admission test and spent the next year at Woodward Prep School, housed in the old YMCA building at 18th and G streets in downtown DC.

Woodward Prep was a stopover for boys who had disciplinary or educational problems. Safer had neither, but he had a good time at the school, where he became proficient in squash, handball, and other sports. He would win the bowling championship at George Washington University a few years later. At Woodward, he won the school table-tennis championship and was editor of the newspaper.

After his year at Woodward, Safer enrolled in the neighborhood college, George Washington University. There he came under the influence of Professor Edward Acheson, brother of US Secretary of State Dean Acheson. Edward Acheson taught an economics course that Safer took. During a lecture on the banking system, Acheson explained that the amount of money a bank could lend was based on a formula developed by a math professor decades earlier. Acheson had written to the math professor asking about the formula, only to learn that the professor had died, so he had taken the problem to the GW math department and asked the professors how it was derived, to no avail. Safer was curious and started to work on the formula’s derivation.

“What motivated me I don’t really know,” he recalls, “but when I went home that evening, I looked up the data on which the formula was based and began to think about it. A couple of days later, I went to Acheson with my results. He looked over my figures and asked me to come back that afternoon. It turned out that I had derived the magic formula correctly.”

Acheson had the young man present his explanation to his classmates and soon asked him to work as his assistant.

Safer had one semester left before getting his economics degree at GW when Japan bombed Pearl Harbor. The day after the attack, the 19-year-old joined the Army Air Force as a flying cadet. He served in India, Burma, and China. The most dramatic incident in his military career occurred near the end of the war, when he and several other pilots were selected to land by submarine in Japan, where they would serve as forward air controllers. The officer briefing the men told them their mission was critical—and warned them that none of them would likely survive. Before the mission got under way, atomic bombs fell on Hiroshima and Nagasaki and World War II was over.

At the war’s end, Safer voluntarily extended his service by a year so he could be sent to Europe—he wanted to explore London, Paris, Rome, and Athens and see their great works of art. He had been attracted to art since childhood. As a boy, he had enjoyed the use of a camera, framing pictures of pipes, poles, and other austere architectural forms. In Rome he studied the sculptures of Michelangelo, visiting the artist’s sculptures of the Pietà and Moses again and again.

“Since it is generally agreed that the statue of David in Florence was Michelangelo’s supreme achievement,” Safer says, “that statue became my final target.”

It was a target Safer nearly missed when his two-week trip to Rome came to an end by orders to proceed to Athens. Before leaving, Safer says, “I borrowed a Jeep and drove to Florence and found to my great dismay that the building was closed.” Safer sought out the caretaker’s office. In broken Italian and with exuberant hand gestures, he convinced the caretaker to let him in to see Michelangelo’s masterpieces.

“One approaches the great statue of David by walking between a double row of Michelangelo’s heroic figures rising out of unfinished stone blocks, generally called ‘The Prisoners,’ ” Safer recalls. “Seeing those works and the emotional power generated by the contrast between the polished marble sculptures and the unfinished stone bases fixed firmly in my mind the power of the abstract, a concept that has remained an essence of my sculpture. All of this came to a head in one period of two hours—two hours that undeniably changed my life.”

While in the military, Safer took some electronics training and grew interested in that field. On his return from Europe, he traveled to Boston to meet with the dean of admissions at MIT. The dean told Safer he could be admitted based on his grades, but because he had little college background in math and physics he should take a year of undergraduate courses in those subjects. After four years in the military, Safer couldn’t see himself spending another year “marking time.”

“My father was a lawyer and very much wanted to see me follow the same path,” he says. “So I sent applications to law schools at Harvard, Yale, and Columbia. Yale and Columbia sent back requests for me to write long essays about why I wanted to go to law school. Harvard sent me a form telling me I was admitted. I wrote back that I would be there.”

After law school, Safer chose a line of work that had nothing to do with law—he took a job with a Cleveland television station. In three months, he was program director. He created an evening news program that quickly drew a greater audience than the competition’s. In Cleveland, Safer became more serious about photography and began producing works of abstract photographic art.

Safer’s communications career ended when his father became terminally ill and the son returned to Washington to handle his businesses, one of which was real-estate development. That led the young Safer to a career in finance and a place of power in Washington banking circles. Wingtipped dealmaker became Safer’s daytime persona, but at home it became that of a sculptor.

He says his passion for sculpture was sparked at the old Trader Vic’s restaurant on 16th Street in downtown DC, where one evening he found himself idly twisting a swizzle stick over the flame of a candle and discovered that he could “control shape and space.”

Safer began creating small pieces of sculpture in 1957. He worked mostly with Lucite—sawing, grinding, heating, bending, and polishing the translucent plastic into sculptural forms, first in his basement, then in the studio he had created in his garage.

In 1960, he and some friends decided to create a venue for contemporary art. The Washington Gallery of Modern Art was a short-lived gallery near Dupont Circle. A show of van Gogh’s paintings attracted the largest crowd in its brief history, but the gallery also displayed most of the major names in the art world of the 1950s and ’60s, including Louise Nevelson, Jim Dine, Robert Rauschenberg, and Andy Warhol. When it closed in 1968, its collection was sold to the Oklahoma City Museum of Art for $110,000.

Through the gallery, Safer met Jim Twitty, the only artist he would ever call a close friend. Twitty had retired from the Air Force and then studied painting. He showed up at the gallery with other artists to sand and paint walls to get it ready to show pieces never before displayed in DC. From his appearance in paint-splattered Air Force fatigues and his mild manner, Safer assumed Twitty was a former enlisted man. On opening night, he asked Twitty’s wife, Anne, where the couple had been stationed last. Homestead Air Force Base near Miami, she said—where Jim had been commanding officer.

Now Twitty was a successful artist and teacher at the Corcoran School of Art. His abstract works include “Blue Water,” an acrylic on canvas at the National Gallery. Safer invited Twitty to his home to see his sculptures. “Jim did not seem overwhelmed, made some mildly positive remarks, and told me to keep working,” Safer recalls.

Twitty left Washington for two years to teach at the University of Leeds in England. On his return, Safer invited him to see what he had turned out in the interim. “He told me I was now doing first-rate work and should begin to think of myself as a professional,” Safer says.

Twitty then made a pronouncement. “He told me that a true professional must exhibit his work publicly,” Safer says. “I remember his words clearly: ‘You will never reach your full potential as an artist until you go down into the arena, into the blood and the sand, and face the public and the critics with the possibility that you will be gored and that it will be your blood that will be spilled into the sand.’ ”

Safer says he handled the life-changing advice in a very human way: “I ignored it.”

For more than a year, Twitty pestered Safer to exhibit his work. When Safer said he suspected Twitty’s judgment about his work had more to do with friendship than talent, Twitty replied, “If you don’t think I can be an impartial judge, pick someone you respect who could.” The Washington Star’s art critic at the time was Frank Getlein. Twitty introduced the two, and Getlein was taken with Safer’s art—years later, he wrote the text for Safer’s first art book, titled John Safer.

After the introduction, Getlein arranged for the artist’s first major exhibit, at the Pyramid Gallery near Dupont Circle in 1970. More than a thousand people came to opening night. The show sold out, critical reception was positive, and the Washington Post ran a three-page review with pictures of Safer’s Lucite sculptures. They ranged from “Multicube V,” an eight-foot-high work of interlocking cubes that’s currently at Duke University, to smaller pieces of interlaced Lucite rods.

The Post article caught the attention of Walter Annenberg, a wealthy art collector and then–US ambassador to Great Britain. Annenberg invited Safer to have a show at the embassy in London, and Safer accepted. Weeks passed without further word from the ambassador. When Safer wrote him, a staffer replied that the invitation had been nixed by the embassy’s cultural-affairs officer. On matters of art, even the ambassador couldn’t overrule the cultural-affairs officer.

When Annenberg learned of this, he went to his friend President Richard Nixon, who approached Secretary of State William Rogers, who called Luke Battle, the assistant secretary for cultural affairs, who, it turned out, was a friend of Safer’s and a co-creator of the Washington Gallery of Modern Art. Battle wrote a note to the cultural-affairs officer in London, who quickly wrote a note inviting Safer to have a London embassy exhibit.

In the years following his debut shows, Safer began working in metal. Two forces moved him: “One,” he says, “was that I began to get commissions for large outdoor sculptures, and Lucite is simply not suitable for outdoor pieces.” Nor does it lend itself to monumental works. Second, Safer was as interested in the shapes he was creating as he was in the play of light in and around his sculptures. Producing them in metal would emphasize the lines. In time, he found himself working mostly in bronze and steel.

He typically creates a sculpture first in Lucite, then has it duplicated in metal. He worked initially with a foundry in New York state and now works with the foundry A.R.T. Research Enterprises in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Safer’s Lucite sculptures are generally three to six feet in height; his bronze and steel works range from table size to 75 feet high.

As he began making larger pieces, he moved his machinery, materials, and works in progress into a large industrial space in Kensington. He has been in that studio almost three decades now.

“I am never happier,” he says, “than when I walk in, look around at my tools and equipment, and start to work.”

In 1976, Safer’s Bethesda neighbor Henry Catto—a fan and collector of Safer’s sculpture—was chief of protocol under President Gerald Ford. One of the responsibilities of the office is to select works of art for the President to present as gifts of state. Knowing that King Juan Carlos of Spain was an art connoisseur, Catto selected Safer’s “Limits of Infinity” to give the king. The center part of the sculpture resembles a vertical infinity symbol. “After I carved it,” Safer says, “I was trying to find a way to mount it, and it occurred to me that it would greatly enhance the design if it were enclosed within a metal oval. Well, if you enclose the infinity symbol you have confined it: Voilà! ‘Limits of Infinity.’ ”

At the state dinner following the presentation of the sculpture to King Juan Carlos, Safer went through the receiving line and met President Ford, who in English introduced the sculptor to the king. Safer told Juan Carlos he hoped he would like his work.

“Sadly,” Safer says, “the king showed no reaction to Ford’s words, gave me a brief handshake, and turned to the next person in line. I was disappointed, but my experience with kings is limited, so I thought perhaps kings don’t show much emotion.”

Later at dinner, Safer was introduced to the Spanish ambassador, who told him that King Juan Carlos loved the sculpture, and he insisted on introducing Safer to the monarch. Not wanting to get the cold shoulder a second time, Safer told the ambassador they already had met. The ambassador persisted, took Safer by the arm, and marched him to the king, introducing Safer in Spanish as the sculptor of “Limits of Infinity.” The King’s face lit up. He told Safer his sculpture would occupy a place of great honor in his collection.

Some years later, when Henry Catto was ambassador to the United Kingdom under President George H.W. Bush, he gave Safer another show at the London embassy. In honor of the ambassador and his wife, Jessica, Safer presented the embassy with his work “Bird of Peace I,” which is now on display in the embassy’s lobby under the Great Seal of the United States.

In the late 1970s, Safer was introduced to Walter Boyne, then director of the National Air and Space Museum, who was looking for a sculpture for the museum. He wanted something that would represent man’s first flight. They began talking about the Wright brothers and Kitty Hawk. Boyne pointed out that the Wright brothers’ flight was the first powered flight but that the Montgolfier brothers’ 1783 balloon ascension in Annonay, France, was actually man’s first flight.

“As I heard those words,” Safer says, “the image came to me of that relatively clumsy balloon rising so slowly that it almost appeared to be standing still but nonetheless was opening space to mankind.” From that image, he created the sculpture “Web of Space.”

Boyne created the annual Air and Space Museum Award and uses “Web of Space” as its trophy. Two are presented each year: one for lifetime achievement, the other for outstanding accomplishment in the air-and-space field. Boyne later wrote the text for the book Art in Flight: The Sculpture of John Safer.

When the Air and Space Museum’s Udvar-Hazy Center was built in Chantilly, Safer was commissioned to create the sculpture that stands at its entrance.

“When I designed it, I was trying to capture a desire inherent in mankind to break the bonds of gravity and soar through the air,” Safer says. Donald Engen, the Air and Space Museum director who commissioned the work—a much-decorated Word War II aviator himself—went to Safer’s home to discuss the proposed piece. When he saw the model Safer had prepared, he said, “No discussion necessary. When I look at ‘Ascent,’ I feel myself coming up off the deck, pulling full power.”

“Challenge,” another Safer sculpture at Udvar-Hazy, was originally commissioned for an office building in Bowie. When Christa McAuliffe, the first schoolteacher in space, was killed in the Challenger space-shuttle disaster, the president of Bowie State contacted the building’s developer and offered to cosponsor the sculpture as a tribute to McAuliffe, the university’s most famous graduate. When Safer learned about the change of purpose for the piece, he was at first stunned.

“I had been working for six months on a sculpture for the lobby of an office building,” he says, “and was told to totally change its theme.” But before he could speak, “images leaped into my mind and I saw my sculpture, ‘Challenge,’ as a completed whole. Even the title came to me at the same instant.”

Safer told the developer he would do as he requested.

“I went to work cutting, grinding, polishing, shaping, and within a week had a model complete in Lucite. I took the model to the art foundry, and within four months ‘Challenge’ was shipped to the building in Bowie.”

Years later, Joy Safer, John’s wife, persuaded the owners of the building to donate the piece to the Udvar-Hazy Center.

John Safer is a fluid writer—several of his written works can be found on his Web site, johnsafer.com. One is a historical account of the late senator Eugene McCarthy and the Vietnam War. Safer was McCarthy’s neighbor and friend—he urged McCarthy to run for President and became his national campaign director. Safer is proudest of an article he wrote on the lasting appeal of Shakespeare’s Hamlet.

But he expresses himself most powerfully in his sculpture.

“When I conceive of a design,” he says, “I can immediately see it as a completed whole. I can look at it from above and below and from all sides. I can see it in such detail that if I could communicate to others the image in my mind, there would be no need to create the sculpture.

“Of course, I can’t communicate that image without actually creating the sculpture, so that is what I must do. And from that point, ‘must’ is the controlling word. That is where the excitement comes in. I can’t wait to see the finished whole. And then, finally, the moment arrives when I can step back and see what I have created. It’s an indescribable sensation, and one of the principal things that make life worthwhile.”

Most important, Safer says, is creating works that make a difference to others: “My ultimate reward is to learn that people who saw one of my sculptures felt better about themselves or the world they live in. My daughter once relayed the remark of a security guard at the Wilmer Eye Institute, who told her that when she felt bad she would sit in front of ‘Quest’ for a few minutes: ‘Then somehow I feel better.’ ”

This article first appeared in the December 2010 issue of The Washingtonian.