Walking around Cheye Calvo's living room in the Prince George's County town of Berwyn Heights, it's hard to believe it was a scene of such violence and heartbreak. Calvo stands by the fireplace in a green L.L. Bean sweatshirt, jeans, and Crocs.

"Want to see them?" he asks, pointing to a wooden box. On top of it are a framed picture of two black Labradors, a figurine of two dogs, and a stuffed toy puppy. He opens the box, revealing two large Ziploc bags. He takes one in his left hand–"Payton," he says—and lifts the second in his right:"Chase. You know by size."

At seven years old, Payton was slightly larger than four-year-old Chase. Calvo had both dogs cremated in August 2008 after they were shot in a botched drug bust by the Prince George's County Sheriff's Office and the county's Narcotic Enforcement Division.

Calvo, the mayor of Berwyn Heights, sued the sheriff's office and police department. In January, just before the trail was to begin, the two sides reached an agreement to settle out of court. Though Calvo will be paid an undisclosed sum, he says his aim in bringing the suit was to change policies on the use of SWAT teams.

Calvo's case isn't the only recent lawsuit over the use of SWAT teams by local law-enforcement agencies. One week before Prince George's settled with Calvo, another high-profile case came to a close: Fairfax County agreed to pay Anita and Salvatore Culosi Sr. $2 million in reparation for the death of their son, 37-year-old Fair Oaks optometrist Salvatore Culosi, who was shot during a SWAT raid in 2006.

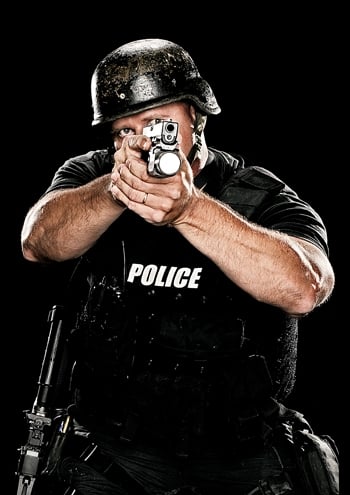

The use of SWAT'—Special Weapons and Tactics—teams was once reserved for worst-case-scenarios. In the United States, the units were first formed in the late 1960s in response to incidents such as the 1966 University of Texas massacre—in which a sniper shot and killed 16 from atop a campus tower—and the 1965 Watts riots in Los Angeles. SWAT teams were designed to defuse situations that would put the public at high risk, such as terrorist threats, hostage situations, and riots. The paramilitary-style units are more heavily armed than regular-duty police officers, often carrying submachine guns.

But the use of SWAT teams has become surprisingly common among American police forces. According to a study by Eastern Kentucky University criminologist Peter Kraska, SWAT deployments in the United States went from about 3,000 in 1980 to 45,000 by 2007.

The Calvo and Culosi cases generated media attention and have led to changes in Prince George's and Fairfax counties. But some think it will take another violent incident before more police departments rethink their policies on when and how they use SWAT teams.

"Even if SWAT teams get the address they're looking for every time, you're sending cops dressed up like soldiers to break people's doors down, usually in the middle of the night, for a nonviolent offense," says Radley Balko, author of a 2006 Cato Institute report, "Overkill: The Rise of Paramilitary Police Raids in America." Says Balko: "That's not an image most people in a free society would see. I guess they do now."

Next: In Maryland, SWAT teams were deployed 1,618 times between July 1, 2009 and June 30, 2010.

What happened at Calvo's home on the evening of July 29, 2008, was well covered by national media: After walking his dogs, he brought in a package addressed to his wife, Trinity Tomsic, thinking it was a shipment of gardening supplies. He was wrong. The package contained 32 pounds of marijuana that had been intercepted by police and then delivered to his home.

Calvo was upstairs when he heard his mother-in-law, Georgia Porter, scream. The Prince George's Sheriff's Office SWAT team had burst through the front door and killed both dogs. Tomsic came home to find Calvo and Porter handcuffed, pleading their innocence.

About a week later, then-sheriff Michael A. Jackson and then-police chief Melvin C. High—now the sheriff—held a press conference in which they said that a FedEx driver had been delivering large quantities of marijuana—totaling 417 pounds—to unsuspecting recipients so an accomplice could retrieve it before the addressees arrived home. High was nevertheless reluctant to clear Calvo and Tomsic from any wrongdoing, and both departments continued to defend their officers' actions.

As traumatic as Calvo's experience was, what happened to Salvatore Culosi was much worse. On January 24, 2006, Culosi went outside to pay a friend—undercover detective David Baucom—money he owed for a sports bet. Since meeting Culosi in October 2005, Baucom had encouraged him to increase what had begun as friendly wagers on sporting events to larger bets. When Culosi wagered $1,500 and lost, Baucom said he'd come by to collect his winnings.

Little did Culosi know that Baucom had called in the Fairfax SWAT team to have him arrested for running a gambling ring. It was during this surprise initiative—in which SWAT officers arrived in military-style gear—that officer Deval Bullock says his finger slipped on the trigger. The bullet tore through Culosi's chest, killing him.

By the time the parents' case was due to be heard on January 18, there was only one remaining defendant, Bullock, because US District judge Leonie M. Brinkema had dismissed the suit against the county, police chief David Rohrer, and Lieutenant James Kellam, head of the SWAT team. The family filed a motion to reconsider with Brinkema and appealed to the Fourth US Circuit Court of Appeals in an effort to get those defendants reinstated. After both efforts failed, the Culosis agreed to a settlement with the county in January.

Neither Maryland nor Virginia has a state law governing the use of SWAT teams, so each jurisdiction is left to do as it sees fit. There is also no DC or federal law governing the District's SWAT deployments.

In Maryland, SWAT teams were deployed 1,618 times between July 1, 2009, and June 30, 2010. Twenty-three percent of the deployments, or 373, were in Prince George's County, including 200 for nonviolent crimes. In the same period, Montgomery County had two deployments for nonviolent crimes, Howard County had 28, and Anne Arundel had 53.

No such statewide statistics are available in Virginia. However, Fairfax County Police spokesperson Mary Ann Jennings says Fairfax had 105 deployments for that same period. After repeated requests, neither Arlington nor Alexandria provided its data. According to Lieutenant Robert Glover of the Special Operations Division, the District's police department had 76 deployments; of those, none were for nonviolent crimes.

Comparisons among jurisdictions can be tricky. Like Prince George's County, Baltimore City has lots of drug-related crime and yet doesn't use SWAT teams nearly as often—the city had only 64 deployments for nonviolent crimes in that same period.

But that may be an unfair comparison, says Baltimore police spokesman Anthony Guglielmi: "We have a dedicated unit that does drugs and violent crime—that's all they do. Our guys are specially trained in drugs because it's Baltimore."

Still, when sending a SWAT team is an option, Guglielmi says, his department always uses a risk assessment to determine whether a SWAT team is an appropriate use of force—something Prince George's doesn't do. Guglielmi was reluctant to go into the specifics of the checklist—it's not something he wants would-be criminals to know—but he says it takes into consideration whether a suspect has a criminal background, whether he or she has weapons, and whether the incident poses a threat to the public.

Montgomery County follows a similar procedure, says Captain Darryl W. McSwain, director of the police department's Special Operations Division. All of the county's search warrants are reviewed by an executive officer, and if a SWAT team is being considered, the SWAT sergeant or Special Operations Division deputy director looks for details—the location of the incident, whether the suspect has a violent history, gang affiliations, prior arrests, firearms—that may indicate the need for a SWAT team. Low-risk warrants are served by detectives and patrol officers who aren't as heavily armed.

In a case like Calvo's—in which drugs were sent to an address whose residents had no criminal background or registered weapons—McSwain says the use of a SWAT team wouldn't be automatic: "Unless there is a reason to believe that the warrant service would be high risk, we would not automatically assume the risk."

According to Prince George's police spokesperson Captain Mistinette Mints, prior to the Calvo case the county issued all of its search warrants—regardless of the details of the case—by sending a SWAT team outfitted with shields, helmets, and a battering ram.

Next: I look out the glass pane to a gun in my face and someone saying, 'Open the door.' "

In a Berwyn Heights living room a couple of blocks from Calvo's home, Charles and Wanda Harris talk about how such a scenario can affect a family.

"It was about 6 AM when they were beating on the door," says 51-year-old Wanda as she recounts the events of March 23, 2009. "I couldn't imagine who was beating on the door. I look out the glass pane to a gun in my face and someone saying, 'Open the door' "

The Prince George's police SWAT team was searching for a gun it believed belonged to the Harrises' 20-year-old son, Charles III. A day earlier, the couple's 16-year-old niece, who had been living with the family since her mother died in 1996, called police to say her cousin had pulled a gun on her.

"We don't even have a gun in the house," says the elder Charles Harris, shaking his head. "Never had a gun in the house. My son is a good kid."

The niece had lied to help her 25-year-old sister, who was living in the District, obtain custody of her. It worked: The younger Charles was charged with assault in the first and second degrees and with use of a deadly weapon. A warrant was issued for his arrest. Charles—a graduate of Bladensburg High School who had taken honors classes and run his father's cleaning business for six months while his father was laid up by acute anemia—spent a month in jail before the family could afford bail, which defense lawyer James Zafiropulos got knocked down from $300,000 to $1,800.

The SWAT team ransacked the younger Charles's room—pulling out drawers of clothes, breaking bowling trophies he'd won as a child. They found nothing, and charges were dropped that July.

The incident was two years ago, but it still haunts the family. "After going through this, he can't get himself together," Wanda says of her son. "He just can't."

Since the Culosi incident, Fairfax police have started to use a threat assessment to determine whether a SWAT team is needed. Previously, a detective made a request for a SWAT team simply by calling a Special Operations commander. Now, unless it's a hostage situation or other threat that requires an immediate tactical response, that same officer would need to fill out an eight-page form and have three levels of command sign off on it.

Nicholas Beltrante, an 83-year-old retired DC police sergeant who lives in Alexandria, wants the county to hold the police force accountable for mistakes and miscalculations. That's why he formed the Virginia Citizens Coalition for Police Accountability last April.

Beltrante is campaigning for a citizens' review board to become a part of Fairfax County's government—something he thinks should be a given for such a large community. He's garnered the support of organizations such as the ACLU of Virginia and the National Police Accountability Project.

In a letter to Beltrante last June, Fairfax County Board of Supervisors chairman Sharon Bulova said the board would pursue his suggestion and had recently met with Police Chief Rohrer to discuss it. More than six months later, Bulova wrote to inform Beltrante that the police chief can't make a decision until Fairfax County Executive Anthony Griffin and County Attorney David Bobzien have reviewed the matter. According to a county spokesperson, there should be a decision soon.

In Calvo's case, the details of his settlement with the county aren't final, but it will mandate changes in police policy. And the settlement is a legally enforceable document he could use to sue if those new rules aren't followed. Calvo hopes he doesn't have to take that step. For now, he's looking ahead.

Calvo is celebrating his upcoming 40th birthday by hosting a fundraiser on March 26 for the Payton and Chase Fund for Animal Causes, a community fund he recently launched. The goal is to raise money to support animal rescues and encourage the humane treatment of animals.

Calvo doesn't want to be known always as "the mayor whose dogs were shot." He and Tomsic plan to start a family one day and move on from this ordeal. Yet an occasional missive from a stranger won't let him move on entirely. "I got a message last night on Facebook about a SWAT raid in Bowie," says Calvo. "They're still out there."

This article appears in the April 2011 issue of the Washingtonian.