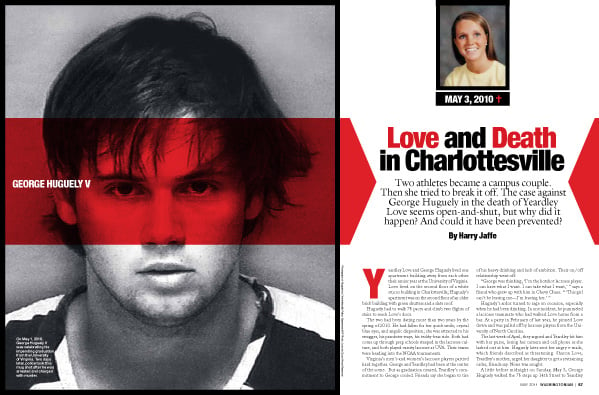

Yeardley Love and George Huguely lived one apartment building away from each other their senior year at the University of Virginia. Love lived on the second floor of a white stucco building in Charlottesville; Huguely’s apartment was on the second floor of an older brick building with green shutters and a slate roof.

Huguely had to walk 75 paces and climb two flights of stairs to reach Love’s door.

The two had been dating more than two years by the spring of 2010. He had fallen for her quick smile, crystal blue eyes, and angelic disposition; she was attracted to his swagger, his prankster ways, his teddy-bear side. Both had come up through prep schools steeped in the lacrosse culture, and both played varsity lacrosse at UVA. Their teams were heading into the NCAA tournaments.

Virginia’s men’s and women’s lacrosse players partied hard together. George and Yeardley had been at the center of the scene. But as graduation neared, Yeardley’s commitment to George cooled. Friends say she began to tire of his heavy drinking and lack of ambition. Their on/off relationship went off.

“George was thinking, ‘I’m the hotshot lacrosse player. I can have what I want. I can take what I want,’ ” says a friend who grew up with him in Chevy Chase. “ ‘This girl can’t be leaving me—I’m leaving her.’ ”

Huguely’s ardor turned to rage on occasion, especially when he had been drinking. In one incident, he pummeled a lacrosse teammate who had walked Love home from a bar. At a party in February of last year, he pinned Love down and was pulled off by lacrosse players from the University of North Carolina.

The last week of April, they argued and Yeardley hit him with her purse, losing her camera and cell phone as she lashed out at him. Huguely later sent her angry e-mails, which friends described as threatening. Sharon Love, Yeardley’s mother, urged her daughter to get a restraining order, friends say. None was sought.

A little before midnight on Sunday, May 3, George Huguely walked the 75 steps up 14th Street to Yeardley Love’s apartment house. He took a left across the parking lot and a right into the outdoor stairwell to the second-floor landing in front of number 9. The white metal door contained a tiny peephole.

The door was not locked.

A classmate of George Huguely’s at Bethesda’s Landon School who also was attending UVA recalls seeing him that Sunday morning. Huguely was dressed in sweats, his hair unkempt, his eyes bleary.

“He was a lot bigger than he was at Landon,” the classmate says. “He was huge.”

Huguely had been lifting weights and working out to keep pace with the best college lacrosse players in the country. The team roster lists him at six-foot-two and 209 pounds.

Yeardley Love was petite; she looked about half his size.

The UVA campus was bustling that first weekend of May. Huguely’s parents, Marta Murphy and George Huguely IV, were in town for senior weekend to celebrate the end of the regular lacrosse season and cheer the teams into the NCAA championship round. They had split up in 1996, when Huguely was nine, and divorced two years later following testy court battles over money and custody of George and his younger sister, Teran.

On Sunday, Huguely joined his father and a few friends for a round of golf at the Wintergreen Resort, in the rolling hills 30 miles west of Charlottesville. Huguely’s roommate saw him drinking a beer at 10 am and “starting to get a little bit drunk,” according to later testimony. Huguely continued to drink on the links; by the end of the round, he was swatting at the ball and skipping holes. After dinner with family members, he continued to drink beers in his apartment. By 11 pm, the roommate said, “he was really drunk.”

When he walked into Love’s apartment sometime around 11:15 pm, she was in her bedroom. Huguely kicked in the bedroom door. Anna Lehmann, a fourth-year biology student who lived in the apartment below, heard arguing and loud banging.

Then silence.

Next: Love's roommate calls 911

Caitlyn “Caity” Whiteley, Yeardley Love’s roommate, arrived at their apartment just after 2 am with her friend Philippe Oudshoorn. Love and Whiteley had grown up near each other in the suburbs north of Baltimore. They were teammates on the UVA lacrosse squad.

They had spent that Sunday together, eating and visiting and drinking. At 10 pm or so, they returned to their apartment. Caity wanted to go out, but Yeardley was tired and a bit tipsy. She took a shower, put her hair in a ponytail, slipped into bed, and took a nap. She had closed the door to her bedroom.

When Caity returned four hours later, she saw the hole in Love’s bedroom door and rushed inside. She found her friend lying face down on a pillow. Whiteley and Oudshoorn couldn’t wake her. They called 911.

“Is there a heartbeat?” the dispatcher asked.

Oudshoorn checked. “No,” he said.

The dispatcher put out a call about an “unresponsive female.”

Charlottesville-Albemarle Rescue Squad members expected to find a student passed out from drinking. They discovered Yeardley Love in a pool of blood.

“When the body was turned over, oh, my gosh, there were obvious injuries,” Charlottesville police chief Tim Longo told the Daily Progress.

Love had a large bruise on the right side of her face. Her right eye was swollen shut. Her chin was bruised and scraped. Rescue-squad members “attempted life-saving procedures,” according to police reports.

She was pronounced dead at the scene.

Since Jefferson established the school in 1819,

no student had ever killed another.

Detective Lisa T. Reeves was at home that early Monday morning. Sergeant Shawn Bayles and Detective Michael Flaherty called her to Yeardley Love’s apartment. Reeves put her black hair in a French twist and drove to 222 14th Street. She examined Love, saw the bruising and swelling, and determined that the injuries “suggested her death was not of natural causes.

Reeves, a slim woman with dark-blue eyes, had been a cop more than nine years, the last three in Charlottesville’s investigations bureau. She was no stranger to violence, but murders were rare in this town.

Since Thomas Jefferson established the school in 1819, no student had ever killed another.

Reeves questioned Whiteley and Oudshoorn at the police station. They told her that Love had recently ended her relationship with George Huguely and that he lived down the street. At 7 am Reeves drove back to Huguely’s apartment house at 230 14th. She went up one flight to number 6 and knocked. Huguely opened the door.

“I am Detective Reese,” she said. “I am investigating a crime.”

He agreed to go to the Charlottesville police station; she drove them to the low-slung brick building about a mile and a half away in the center of town. Huguely rode shotgun.

George Wesley Huguely V waived his right to remain silent. He didn’t call his parents. He didn’t contact a lawyer.

“George Huguely admitted that on May 3, 2010, he was involved in an altercation with Yeardley Love,” Reeves wrote in the first of her affidavits, “and that during the course of the altercation he shook Love and her head repeatedly hit the wall.”

Huguely told Reeves he kicked in Love’s door with his right foot. The detective said his leg showed injuries “that are consistent with kicking an object, such as a door.”

In a second affidavit, Reeves wrote: “Hugely stated that at one point during the altercation he saw blood coming from Yeardley Love’s nose” and that after the altercation “he pushed Yeardley onto her bed and left.”

After giving his statement, Huguely was arrested and charged with the murder of Yeardley Reynolds Love.

Police returned to Huguely’s apartment to execute a search warrant. They found the blue cargo shorts he said he was wearing during the assault. His passport was in a pocket.

Next: Huguely's life behind bars

Nine months later, on a sunny Saturday in mid-February, the University of Virginia campus is alive with promise.

The UVA men’s lacrosse team opened its 2011 season against Drexel. It lost the previous season’s NCAA semifinals to Duke, 14–13. The team started the new season ranked number one. It beat Drexel 12–9.

The men’s basketball team pulled off a 61–54 upset of rival Virginia Tech. Parents and students are basking in the midday sun on the Corner, a row of shops and bars across from the campus, or “the Grounds” in UVA parlance.

About four miles southeast of campus, on a hilltop off Interstate 64 toward Monticello, George Huguely is in a four-unit cellblock of the Albemarle-Charlottesville Regional Jail. A 20-foot chain-link fence topped by coils of concertina wire encloses the peach-colored buildings. On this clear day, you can see the tops of the Blue Ridge Mountains rolling away to the north and east. Huguely’s cell has a window, but a jail building blocks his view.

Captain J. Rush is in charge of the afternoon shift. She says the jail houses prisoners in minimum-security, medium-security, and maximum-security units. Which is Huguely’s? “He’s max,” she says.

He’s confined alone in a two-person cell, about 8 by 12 feet. For a few hours a day, he shares a common space housing a table and a TV with three other inmates. The jail has outdoor recreation areas and two gyms, one with a basketball court. “There’s plenty of room to walk around,” Rush says.

Charlottesville Commonwealth’s Attorney Warner D. “Dave” Chapman originally filed first-degree murder charges against Huguely. In January, he added five more charges, including felony murder, robbery, and grand larceny (because Huguely took Love’s computer).

Chapman is preparing for trial and negotiating a plea with Huguely’s defense team, Charlottesville lawyers Francis McQ. Lawrence and Rhonda Quagliana. Neither side seems to want a trial. Chapman did not file a capital-murder charge, which might have allowed a death sentence. Lawyers familiar with the county’s criminal system predict that Huguely is facing ten years to life behind bars, depending on the outcome of the plea negotiations or trial.

"You have to wonder which kid you would rather have—the dead one or the one in prison?"

Few people are willing to talk about the crime—not police, lawyers, families, or friends. The details are too intimate, the feelings too raw. Friends of Huguely feel guilty; friends of Love have been implored by her mother and sister not to talk about her or the incident.

Sharon Love has established the One Love Foundation to fund projects in her daughter’s memory. It has raised $1 million for a new lacrosse field and a scholarship at her alma mater, Notre Dame Prep outside Baltimore. The UVA girls’ lacrosse team retired her jersey on March 6 at the second home game of the 2011 season.

The Huguely family has remained silent. Marta Murphy, George’s mother, tried to have the court records of her 1998 divorce from his father sealed.

UVA has cleansed its files of George Huguely V. “Any record of him has been erased,” says Andrew Seidman, managing editor of the student newspaper, the Cavalier Daily. “The university has ordered a top-down gag order on the matter.”

As the first anniversary of Love’s death approaches, echoes of the pain and horror still reverberate—from the UVA campus to Landon and Notre Dame Prep, in conversations among Yeardley’s and George’s peers and friends of the families.

Could this crime have been prevented? What could have provoked—or enabled—George Huguely to take a life? Can the seeds of this tragedy be found in the family’s history, the lacrosse culture?

“You have to wonder which kid you would rather have,” says an acquaintance of George Huguely IV, father of the accused and a longtime Washingtonian. “The dead one or the one in prison?”

Next: Lacrosse—a scapegoat for violence?

Yeardley Reynolds Love and George Wesley Huguely V met as freshmen—or first-years, in UVA terms. Though the entering class had more than 3,000 students, there’s no way the two wouldn’t have encountered each other—they were part of the lacrosse culture, a select group within an elite college.

By many accounts, Love grew up in the embrace of a warm family, with her parents and older sister, Lexie. Her father, John, was an investor. He died of prostate cancer when Love was in high school. Her mother, Sharon, raised the two girls.

At Notre Dame Preparatory School in Baltimore County, Love played field hockey and lacrosse.

“Yeardley was an outstanding young lady—joyous, spirited, a wonderful person,” Sister Patricia McCarron, the school’s headmistress, told Fox News. “We are proud to call Yeardley one of our girls.”

It was as if she was bred for lacrosse, the ball game first played by Iroquois tribes. Her father loved the sport. Her uncle, Granville Swope, played varsity at UVA. For some families in Baltimore County, lacrosse is a way of life.

“To paraphrase the great coach Vince Lombardi,” former Baltimore Sun reporter Jamie Stiehm wrote for the Web site Politics Daily, “lacrosse is the only thing to many families who send their children to single-sex private schools in the green northern reaches of the city.”

The same might be said about the northern suburbs of Washington, where George Huguely V came of age. He played lacrosse at Mater Dei, a Catholic school in Bethesda, and became a star at Landon, a lacrosse powerhouse that often ranks among the nation’s top teams and sends players to Ivy League schools—and UVA.

Both Yeardley Love and George Huguely were recruited to play lacrosse at UVA. As soon as they arrived on campus, they were thrown together, socially and athletically.

“Athletes ate together, traveled together, lived together,” says a Virginia alum. “They had their own lifestyle. If sororities and fraternities had their own private culture, athletes had one even beyond that—whatever the sport. Lacrosse was not that different.”

Love and Huguely met and bonded through lacrosse connections, and when they started dating they were part of a close community. Lacrosse carries connotations of wealth and privilege along with its elite athletic image, which creates a stereotype through which some observers seek to explain Yeardley Love’s violent death.

"Athletes ate together, traveled together, lived together. If sororities and fraternities had their own private culture, athletes had one even beyond that."

Lacrosse has become a kind of scapegoat for the crime—as have Landon and to some extent UVA. But it’s probably more instructive to look to the families for clues.

Both students have strong and caring mothers.

“Marta is one of the nicest, sweetest people you will ever meet,” a man who knows the Huguely family socially and professionally says of George’s mother.

In the days after her daughter was killed, Sharon Love went to Charlottesville to comfort Yeardley’s friends and lacrosse mates. She met with the boys’ and girls’ squads and encouraged both to play in the NCAA tournaments. She has never uttered a negative comment in public about any aspect of her daughter’s demise.

When Yeardley’s father, John, died in 2003, his wife and daughters bonded in his honor. In her eulogy for Yeardley, Sharon Love said of her daughters: “Rather than giving in to grief, they vowed to stick together and make their father proud.”

Next: Huguely's broken family

George Huguely is the fifth generation of a prominent family in the nation’s capital.

The Huguely family’s roots are in lumber. Next year will mark a century that the Huguely family has been in the lumber trade in the capital. In 1912, George W. Huguely Sr. and William Galliher opened a lumber yard at what was then James Creek Canal and N Street, Southwest, close to the Maine Avenue waterfront.

In 1916, Galliher & Huguely moved north to the corner of Sherman and Florida avenues, near historic LeDroit Park. The capital was a boom town, and the Huguelys prospered by supplying lumber for houses as the city spread north and west.

Huguely bought out Galliher in 1929, and the family has run the company since. Unlike the Hechinger family, which expanded from one store to a regional chain before it failed in 1999, G&H maintained a single location, now a few blocks south of the Maryland line.

When Huguely Sr. died in 1937, he left a $1.4-million estate to his wife, Mabel, and son. George Jr. graduated from DC’s Central High, now Cardozo, and the University of Pennsylvania. He ran G&H for 30 years, from 1937 until he retired in 1967.

The second George did well and lived well. He was a member of Columbia Country Club in Chevy Chase. He liked to sail, bought property in Annapolis, and joined two yacht clubs, Corinthian and Annapolis.

George Jr.’s sons—George III and Geoffrey—expanded the family business into real estate and development, opening the Huguely Companies at 4424 Montgomery Avenue in Bethesda.

The Huguelys went to the best local prep schools and universities. George III, George V’s grandfather, went to Sidwell Friends and the University of Virginia. His great uncle Geoff went to Landon, as did his son, Scott, George V’s uncle, who now runs the lumber company on Blair Road. George IV, father of the accused, worked for a time at the lumber yard but ultimately preferred the family’s real-estate and investing firm.

George Wesley Huguely IV didn’t follow the family path to elite education. The announcement of his engagement to Marta Lissette Sanson in September 1983 says he attended the University of Tampa and the University of Maryland, but it doesn’t mention a degree. Marta got a business degree from Georgetown. The two were married on December 30, 1983.

George V was born September 17, 1987; Teran came in January 1990. Marta, a tall blonde, had done some modeling for Saks Fifth Avenue. She stayed at home to care for the children.

The father didn’t make much of a name for himself in business or development circles, according to real-estate executives. But friends say he earned a reputation as a partyer. He frequented bars in DC such as Mr. Day’s, Nathans, and Beowulf, and was a regular at drinking establishments in Bethesda and Rehoboth Beach, Delaware.

“He was a bar guy,” says a friend of the family. “Not such a bad thing.”

But probably not a good thing for his marriage. Marta and George IV separated in February 1996, according to divorce proceedings filed in Montgomery County Circuit Court. George moved out of the family home on Spring Hill Lane in Chevy Chase.

The parents clashed over George V and Teran. Marta said her husband saw the two children during “brief evening visitations or vacation time.” He occasionally threatened to move back in. On Christmas Day 1996, George IV arrived at Spring Hill Lane, “forced himself into the home,” and took up temporary residence, his ex-wife said in court papers. Marta took the children and moved in with her sister.

Nine days later, on January 3, 1997, Marta filed for divorce. She also filed a motion to have her husband enjoined from “entering” the home. He moved out; she returned with George V and Teran.

Next: "Was there a murderer inside of him?"

In the first months of the nearly two-year divorce proceeding, the parents were admonished not to argue in front of the children. A judge ordered them to attend “coparenting skills enhancement” classes. Under court order, they agreed to discuss the children only if neither was in earshot.

The battle then moved to money. Marta asserted that her developer husband earned more than $100,000 a year. But George asserted in court papers that he was broke and lived off his family.

He claimed in court filings that he and his wife had been living “an unrealistic lifestyle that included a $600,000 home in Chevy Chase (with over $600,000 of debt), a boat, luxury automobiles (BMW and Range Rover), the most costly of private Catholic schools for their two children.”

He said that “the only reason” they hadn’t “lost their home, or worse yet filed for bankruptcy, is because of the largess of her husband’s family . . . .” His father, George III, had lent him more than $1.5 million, he said, adding that he had to liquidate a $450,000 trust set up by his grandfather, George Jr., “to help the family survive.”

Marta argued that her husband was stiffing her and the kids “while continuing to spend excessive amounts on himself for his boat, country club, and vacations.” She said he had told her on many occasions that he would “act poor until he gets rid of her” and then would build a house on a lot he had recently bought. George IV now lives in a house on that lot on River Road.

Meanwhile, he wasn’t keeping up with support payments and legal costs ordered by the court. By December 1997, he owed Marta $11,476.43. Judge James Ryan, who has since retired, found George IV in contempt and sentenced him to ten days in jail unless he made a $1,000 payment. He paid.

“Every time he got in trouble,” says one acquaintance, “his father would bail him out.”

Frustrated in her attempts to acquire financial information, in the fall of 1998 Marta Huguely had her husband’s parents, George III and Elizabeth Huguely, subpoenaed to testify as well as his uncle Geoffrey. Marta’s attorneys moved to garnish funds from the father’s bank accounts and proceeds from property held by the family development firm.

Over the mantle is a boar's head that George Huguely jokingly referred to as "Marta".

Marta Huguely got her divorce on November 4, 1998. The final settlement’s details aren’t public, but it did spell out that Marta would remain in the Spring Hill family home for 14 months, at the end of which her ex-husband was to pay her $100,000. Four years later, she and the children were still in the house because George still owed her money.

The court granted Marta the right to restore her former name, Marta Lissette Sanson.

George IV finally settled up in 2004.

George and Marta pledged in court not to criticize each other, a pledge they might technically have kept. But at George Huguely’s home on River Road, visitors report that over the mantle is a boar’s head that he has jokingly referred to as “Marta.”

“I’m not sure that’s very funny to the children,” one visitor says.

But it might have set a tone for his son, George V.

The boy was ten when his parents were at war in court. He was attending Mater Dei. Its motto is “Work hard, Play hard, Pray hard, and be a Good Guy!” The school has a dress code and a strong educational program; its application asserts that “character development is the school’s top priority.”

Athletics are another priority. George V played football, basketball, and lacrosse at Mater Dei. Its best athletes go on to Georgetown Prep or Landon. George V chose Landon, perhaps because his great uncle Geoff and his uncle Scott had played sports there.

Huguely excelled on the athletic field. He was quarterback on the football team and started his senior year. But the most exalted game at the sports-focused school is lacrosse. Huguely became a star, which ensured him a place at the top of the teenage social order and potentially an invitation to play lacrosse at a top college.

“The kids on the lacrosse team drove big SUVs, they hung out together on weekends, they drank a lot,” says a Landon graduate who didn’t play lacrosse but was part of the crowd. “They got the girls.”

“He was a pretty playful kid,” says a lacrosse teammate. “He was not a great student, but he didn’t care. He was more interested in having fun.”

Says another classmate who played basketball with him: “George had the wealth and entitlement, he was an elite athlete, and he could party hard. You could also see there was a temper there.

“Was there a murderer inside of him? No,” he says. “But a temper and a potential for issues? Yes.”

Next: "George was a big drinker, and his father allowed it."

Landon has an honor code, and violators are brought before the student council. The school refused to comment on Huguely, but a classmate says, “I cannot recall ever hearing him connected with any violations.”

Students say the teacher who had the most influence on Huguely was Robinson “Robbie” Bordley. A Landon grad, he’s taught history for more than 40 years, but his claim to fame is running Landon’s top-rated lacrosse program. He also coaches football.

“Mr. Bordley looked out for George,” says a classmate. “He stood up for him with teachers. They were really close.”

Neither Bordley nor any other faculty member at Landon would comment about Huguely, citing the ongoing criminal case.

No one, male or female, recalls George Huguely’s being aggressive toward females. “Cocky for sure,” says one friend, “but that’s it.”

Students and friends interviewed agree on one thing: Huguely drank a lot.

“That was our scene at Landon,” says one teammate.

But Landon grads point out that the school’s drinking scene was no different than those at Washington’s other boys’ prep schools. “It’s tempting to single out Landon,” says one, “but Landon was not the cause of this tragedy. Maybe it was something in his family life.”

At UVA, George Huguely was no longer a lacrosse star. The team was loaded with top players, some of the best in the nation. Huguely made the squad but was on the second midfield. He played in almost every game and scored some goals but rarely started.

He majored in anthropology and began dating Yeardley Love in his first year. He never joined a fraternity, though he spent a lot of time at the Delta Kappa Epsilon house. And friends say he drank, often with his father.

After the divorce, George Huguely IV moved to a yellow farmhouse on River Road in Potomac, past Swains Lock. He frequented the restaurants Hunter’s Inn in Potomac and Tower Oaks Lodge in Rockville. He never remarried. Women he dated were treated to parties at the yellow farmhouse, visits to a nearby gun club, and trips to Manalapan, Florida, where he kept a boat.

“He had a total Peter Pan complex,” says one. “But he did seem devoted to his kids.”

Marta Sanson remarried; her last name is now Murphy.

"It's tempting to single out Landon, but Landon was not the cause of this tragedy."

George IV tried to spend time with George V in both Potomac and Charlottesville. Through the Huguely Companies, he bought property in Albemarle County, but the venture went into foreclosure last December.

George IV treated George V and his lacrosse buddies to weekends at the family’s beach house on North Carolina’s Outer Banks and took them out on the family’s 40-foot yacht, the Reel Deal. The father, then in his late fifties, liked to show up for lacrosse-team parties. “He tried to be one of them,” a friend says.

“George was a big drinker,” says a former student, “and his father allowed it.”

They didn’t always get along. George IV once called police in the Palm Beach community of Manalapan to report a domestic incident. The two had argued, and the son had jumped from the boat and refused to return. Another vessel picked him up.

It wasn’t the son’s first brush with the law in Palm Beach. In 2007, he was charged with possession of alcohol by a minor.

In his senior year, George seemed to lose his athletic intensity. He got a little soft. “He looked like a teddy bear,” says a UVA official. The Washington Post reported that his teammates called him “Fuguely,” a combination of his name and a common curse word.

If there was a missed opportunity, an event that might have derailed Huguely from his violent train wreck in 2010, it was his arrest in Lexington, Virginia, on November 14, 2008. Officer Rebecca Moss discovered Huguely wobbling drunk into traffic near a fraternity at Washington and Lee University. She told him to find a ride home or face arrest. He began screaming obscenities and making threats.

“Stop resisting,” Moss said. “You’re only making matters worse.”

“I’ll kill all you bitches,” he said, according to Moss’s report.

Moss and another female officer tried to subdue Huguely. He became “combative,” the police chief reported. Moss stunned him with a Taser, put him in a squad car, and took him to the police station.

At his court hearing a month later, Huguely said he didn’t remember much about the night and apologized. He pleaded guilty to public swearing, intoxication, and resisting arrest. He was fined $100 and given a 60-day suspended sentence.

Huguely bragged about the incident to friends, but he never reported it to the university or to his lacrosse coach, Dom Starsia, as both the team and the university required.

Rather than sobering him up, the incident seems to have given him greater license.

Next: From Yeardley's apartment they took towels, sheets, and a pillowcase—all covered in red stains

A feature of Huguely’s rages was that he didn’t remember them the next day, according to friends. But he recalled much of what happened that fateful Sunday night/Monday morning.

It was about 7 am when Detective Lisa Reeves knocked on Huguely’s door. He was lucid enough to tell her details of the previous few hours. He explained that he and Yeardley Love had been dating for “over two years,” Reeves wrote in an affidavit, and had just ended their relationship. And that within the past few days they had “shared e-mail correspondence.” He described their “verbal and physical altercation” at her apartment. He said he had slammed her into a wall and shoved her onto her bed.

Then, he told Reeves, he took her Dell laptop computer and walked out of her bedroom, through the apartment, and down the steps to 14th Street. He took a right, walked past his apartment building to a side street, saw a dumpster, and threw the Dell into it.

Reeves asked Detective James Mooney to check the dumpster, where he found the Dell laptop. She sent it to Fairfax detective Albert Leightley for forensic analysis; he was able to retrieve e-mail correspondence. The exact words were blacked out in affidavits, but they accorded with Huguely’s admission to Reeves and confirmed reports by Love’s friends that Huguely had sent threatening notes to her.

At the police station, detectives clipped hairs from Huguely’s arms and legs and took a swab from his mouth to record his DNA. They searched his apartment and retrieved a white UVA lacrosse T-shirt with red stains on it and the shorts he was wearing during the assault; his passport was in a pocket along with the keys to his Chevy Tahoe.

From Yeardley’s apartment they took towels, sheets, a pillowcase, and a bed apron, all with red stains.

Love’s roommate told police her friend was wearing only panties when she discovered her body. Huguely told Reeves she was wearing a black T-shirt and panties when he left her bedroom. Reeves said she reviewed crime-scene photos and saw the rumpled T-shirt on the floor, as if it “had been dropped.”

It seems to be the only piece of information Huguely had wrong.

A feature of Huguely's rages was that he didn't remember them the next day, according to friends. But he recalled much of what happened that fateful night.

News of Love’s death broke Monday morning. Students stood outside libraries and classrooms, cell phones to their ears.

“I saw George’s photo on the news,” says one of his Landon classmates. “I couldn’t believe it.”

The killing slammed the campus just as seniors were preparing for graduation and making plans for beach week. They had been worried about finding jobs—now they were grieving for two classmates.

“When everything seemed so perfect,” says UVA spokesperson Carol Wood, “and all the seniors had their futures laid out before them, to have this happen to one of their own was more than they could bear.”

Marta Murphy had been on campus for senior weekend. She put out a statement a few days later: “I hope that people can understand that both George’s father and I love our son. We will support George in any way we can—just as any mother or father would do for their child.”

George IV had been in Charlottesville, too, but he didn’t speak publicly.

The men’s and women’s lacrosse teams faced both the tragedy involving two of their own and the prospect of taking the field in the NCAA tournaments. Sharon Love and her daughter Lexie met with both teams.

“They were in that room offering them support and comfort,” says Carol Wood. “She’s a pretty strong woman.”

Sharon urged both teams to play.

Next: "Is Landon to blame for the Huguely situation?"

David Armstrong, headmaster at Landon, woke up that Monday morning in an upbeat mood. He had headed the prep school for six years. Members of the graduating class had been admitted to top colleges. The Landon community had just celebrated its annual azalea festival.

The night before, an old friend and fellow educator had phoned. “Is there a downside to being a headmaster?” the friend had asked.

“On any given day,” Armstrong responded, “something can happen that turns my world upside down.”

Armstrong, 63, had come to Landon in 2004, two years after its faculty had discovered that students had shared answers during an SAT exam. Most were lacrosse players, and one of them was the son of coach Robbie Bordley. In 2006, Armstrong had had to deal with the backwash from the Duke lacrosse scandal, when members of the team were accused of raping a stripper. Five had attended Landon. All were exonerated, but Landon was sullied in the process, and Armstrong was put on the defensive.

On this Monday morning, the headmaster’s cell phone rang as he was walking across the campus.

“Get on the Internet,” the caller said. “We might have a problem.”

“The rest,” Armstrong says in a conference room by his office, “is history.”

News stories about the UVA killing mentioned Landon and repeated the stereotype that Huguely had come from an “elite” school in a “privileged world” where lacrosse players were enabled and allowed to break rules.

Within a week, at least one carload of kids drove by Landon’s playing fields on Wilson Lane yelling, “Murderers!” at students.

“That was disappointing and hurtful,” Armstrong says. “We wanted to make sure our boys were not exposed to unfair insults.”

Neither Armstrong nor anyone else in an official capacity at Landon will comment on George Huguely. But there’s a sense among parents and board members that George Huguely V was a fine student and athlete during his years there. “Why should Landon have to take the blame when the boy was out of our community for four years?” a Landon board member asks.

Landon “hunkered down,” in the view of one parent, and “treated the Huguely matter as if it would just pass. It didn’t.”

The board hired a public-relations firm to try to ameliorate the negative publicity. Still, the press sometimes branded Landon a school for rich bullies.

“I could understand the reaction,” Armstrong says, “but I wasn’t happy. Parts of it were unfair, and the allegations were unjust. I worried less about the press and more about the boys.”

The school held meetings and hired counselors to meet with students. Some faculty contacted Landon alums in Huguely’s UVA class to see how they were handling the tragedy. “We felt a sense of community,” one said.

Some parents and students do criticize Landon for letting athletes, especially lacrosse players, seem to violate rules without facing consequences. But the school has more fans than detractors.

Within a week, at least one carload of kids drove by Landon's playing fields on Wilson Lane yelling, "Murderers!" at students.

“Is Landon to blame for the Huguely situation?” asks Herta Feely, whose two sons are graduates. “Absolutely not. My boys got great educations, and they played sports. It has great athletic programs, but it also has equally good music programs. It has a real brainiac group and a great artistic group.”

Every summer, Landon convenes meetings to evaluate the past year and to plan the next. Last summer, it brought together alumni, trustees, parents, and staff for 14 open forums. “Huguely was the catalyst,” says Armstrong. “Our introspection was certainly much greater, our self-evaluation much deeper.”

Says one parent who attended the sessions: “When we dug deep, we found Landon had problems that needed to be addressed.”

The meetings resulted in many initiatives—but few major changes. The school still stresses “character education,” Armstrong says. “Every student signs honor and civility codes.”

Not everyone thinks that’s sufficient. “It’s clear the school is talking the talk,” says one parent, “but it doesn’t always walk the walk.”

Next: UVA grieves over Love's death

At the candlelight vigil for Yeardley Love three days after her death, UVA’s then-president, John Casteen III, implored students to pay attention—and call attention—to friends who might be in need.

“Don’t hear a scream and not report it,” he told the 5,000 students holding candles in the school’s amphitheater. “Don’t watch abuse. Don’t hear stories of abuse and stay quiet.”

Casteen, in the final months of his 20-year term, was distraught. He met with students, faculty, the Loves, the Huguelys. He wrestled with the what-ifs.

What if George Huguely’s arrest and prosecution in Lexington for drunkenness and fighting with cops had been reported to UVA?

A week after the killing, Casteen met with Virginia governor Bob McDonnell to ask if local law-enforcement authorities could share arrests with universities. McDonnell was noncommittal.

What if Huguely’s teammates had reported his drunken rages, as they should have done under the lacrosse team’s rules? What if Huguely had told his coach about the arrest, as required by the team’s honor code?

One thing has become clear: Athletic honor codes rarely work. Whether at prep schools like Landon or universities like UVA, athletes rarely snitch on themselves or others.

The questions raised in May by the Washington Post’s Sally Jenkins in a column about Huguely remain salient: “[H]is teammates and friends, the ones who watched him smash up windows and bottles and heard him rant about Love. . . . Why didn’t they turn him in? . . . Why did they not treat Yeardley Love as their teammate, too?”

"When everything seemed so perfect, and all the seniors had their futures laid out before them, to have this happen to one of their own was more than they could bear."

These questions also plagued UVA student leaders.

“A lot of people were second-guessing themselves,” fourth-year student Sharon Zanti recalls. “You could see it on the faces of the coaches afterwards. There was a lot of horrific grief on the part of friends and faculty.”

Zanti, fourth-year student Danielle MacGregor, and student-government president Colin Hood spoke with me on a late-winter Sunday on the UVA campus. The students and the university, they say, has used Love’s killing as a catalyst.

“We pulled that night apart,” MacGregor says. “What could we do? What could we change? We settled on bystander behavior. Students need to be trained to react. How can we get people to not be a bystander?”

UVA’s new president, Teresa Sullivan, called for a Day of Dialogue at the start of classes last fall. Pillars around the iconic Rotunda were draped in black. In meetings and conferences, the central question was “Are you your sister’s or brother’s keeper?”

The answer, at least for student leaders, was an emphatic yes. After the Day of Dialogue, they developed a program called Let’s Get Grounded. It offers students a 90-minute training session in how to recognize and react to potential problems, such as alcohol abuse, bullying, and violence. “We are encouraging people to look out for one another,” MacGregor says. “You don’t have to know someone to be an active bystander.”

At a campus known for heavy drinking, how many of their schoolmates are taking them seriously? So far, 1,200 out of more than 15,000 students have enrolled in the program and taken a pledge to intervene if they sense someone is in jeopardy.

“I don’t think anyone faults us for trying to fix it in this way,” Zanti says. “Being an active bystander doesn’t mean you are solving problems, but it can be a start.”

Next: Charlottesville may be the only place in Virginia where the death penalty is hard to get

Charlottesville is a good place for a student to kill someone.

In the wee hours of Friday, November 8, 2003, Andrew Alston, a third-year UVA student, went drinking with friends and his brother, Kenny. They hit at least a couple of bars on the Corner, starting at the Biltmore Grill, moving to O’Neill’s Pub, and grabbing a few burgers at the White Spot.

At 1:30 am, Alston and his friends encountered Walker Sisk, a Charlottesville native, and his friend, Jimmy Schwab. Both were volunteer firefighters well known and liked in the local community.

It’s safe to say that all parties were intoxicated. They began yelling at one another, and a fight ensued. Sisk was stabbed 20 times and was left lying in the street. Police followed a trail of blood to 222 14th Street—the apartment house where Yeardley Love would die a few years after that.

The case went to trial a year later. The defense suggested that Sisk had stabbed himself.

The prosecutor sought a second-degree murder conviction, which carries prison time of up to 40 years. The jury found Alston guilty of voluntary manslaughter. The charge carried a potential sentence of ten years; the jury sentenced Alston to three.

“People feel kicked in the stomach,” said Chief Doug Smythers, then leader of Sisk’s Seminole Trail Fire Department.

Town residents were outraged but not surprised. “Charlottesville is not a red-meat town,” says Hawes Spencer, editor of the Hook, an alternative weekly newspaper. “If you are the defendant in a crime, you definitely want to litigate in this town.”

Virginia is known as a law-and-order state, where the death penalty is often sought and carried out. Charlottesville, because it’s home to the university and the liberal community that surrounds it, is an anomaly. “Charlottesville is an oasis in many ways,” says David Heilberg, a veteran criminal-defense attorney. “It may be the only place in all of Virginia where the death penalty is hard to get.”

The Huguely case has eerie similarities to the Alston case, beyond the fact that police found Alston at 222 14th Street. Alston came from a wealthy family, and his parents financed his defense.

But would George Huguely fare well before a local jury, given his admissions to Detective Reeves hours after Love’s death?

“Probably not,” says Heilberg, president of the Virginia Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers. “There’s not a whole lot to be gained by the defense to go to trial. There are cracks in the case, but not big enough for water to flow through.”

George Huguely V appeared in court via video the day after he was arrested. He wore a gray-and-white prison uniform. His eyes were glazed, his hair rumpled. The public hasn’t seen him since. He waived the right to appear at hearings.

His lawyer, Charlottesville defense attorney Francis Lawrence, has said little beyond his comment in the days after the killing, when he termed it “an accident with a tragic outcome.”

Says newspaper publisher Hawes Spencer: “People went ballistic. The Alston case was still fresh in their minds.”

Commonwealth’s Attorney Dave Chapman filed first-degree murder charges. In July, the Charlottesville medical examiner ruled Love’s death a homicide by blunt-force trauma.

At a December 15 hearing, Francis Lawrence demanded Yeardley’s medical records. He produced experts who testified that she might have died from insufficient blood flow to the brain, caused in part by drugs and alcohol. They said she had amphetamines in her system, which can increase the risk of cardiac arrhythmia. The amphetamines might have come from Adderall, a prescription drug found in Love’s backpack. The pills are standard study aides in college dorms.

The judge denied Lawrence’s request for records covering medications beyond Adderall.

George's lawyer, Francis Lawrence, has said little beyond his comment in the days after the killing, when he termed it "an accident with a tragic outcome."

On January 7, Chapman added more charges: felony murder, which includes murder during the commission of a robbery; robbery; burglary; entering a house with intent to commit a felony; and grand larceny.

Most observers saw this as a move to strengthen the prosecution’s position during plea negotiations. Francis Lawrence saw the bright side: “We think it is significant that the amended charges acknowledge that there was no premeditation.”

Chapman, who has to answer to voters as well as his sense of justice, most likely will start by demanding first-degree murder, with a range of 20 years to life without parole. But he might be satisfied if Huguely pleads to second degree, which would allow a sentence of up to 40 years. “That would be a huge win for Lawrence,” says Heilberg.

Lawrence might start by asking for manslaughter, the sentence handed down for Andrew Alston. It carries a maximum sentence of ten years.

Says Heilberg: “Fran would think he’d died and gone to heaven.”

The question becomes at what point the Huguely family will agree to a deal. Will family members accept George V’s spending 40 years behind bars? Thirty? Twenty? Will they prefer a trial that would expose the young man to weeks of gruesome testimony and details of the night Yeardley Love died?

Next: "She’s dead, George, and you killed her.”

On Monday, April 11, 2011, Sharon Love sat next to her daughter Lexie in the front row of the cavernous chamber of the Charlottesville Circuit Court. Across the courtroom sat the Huguely clan—Marta and her new husband; George IV; George V’s sister, Teran; his grandmother Elizabeth; and other relatives.

The families had traveled to Charlottesville for the first substantial preliminary hearing in the criminal case. Lawyers presented evidence to help Judge Robert Downer determine whether to send charges to a grand jury. Huguely, the accused, waived the right to appear in person or by video.

A parade of witnesses, starting with Caity Whiteley, testified about the details of that first weekend of last May. Whiteley spoke clearly and without emotion about discovering her roommate. “Her hair was all messed up,” she said. “I pulled it from her face and saw the blood. Her eyes didn’t look right. I shook her shoulder. She didn’t respond.”

Francis Lawrence, a tall attorney whose white hair and mustache invite comparisons to Mark Twain, outlined the way he would defend George Wesley Huguely. “He had no intention, no motive,” Lawrence said. “George did not know that Miss Love was dead or had any significant injury.”

During the interview with Huguely on Monday, May 3, videotaped by police, he appeared not to be aware of Love’s fate.

“She’s dead, George,” Detective Reeves said on the video, “and you killed her.”

“I didn’t, I didn’t, I did not,” Huguely responded. “I never did anything that could do that to her.”

Commonwealth’s Attorney Dave Chapman presented witness after witness who punched holes in Lawrence’s defense. Most damaging was testimony by the accused’s roommate and teammates.

Kevin Carroll, Huguely’s roommate, said he was drinking with Huguely in their apartment that Sunday night. Huguely was “angry” because “his dad wanted him to sign something he didn’t want to sign.”

Carroll testified that he went out for more beer just after 11. When he returned, Huguely wasn’t there. Huguely returned after midnight and said he had been downstairs in teammate Chris Clements’s apartment with Clements and another lacrosse player, Will Bolton.

But Clements testified that he had heard Huguely coming down the stairs and locked his door. When Huguely asked to visit, Clements said, “Go away—I’m studying.”

Will Bolton also testified that he hadn’t been with Huguely in Clements’s apartment, as Huguely claimed. With that, Huguely’s alibi was punctured.

It was in that hour that George Huguely had walked the 75 paces to Yeardley Love’s apartment and back.

After you've read the story, head to the comments section below to share your thoughts on:

- Could Love and Hugely's teammates and friends done more to prevent this tragedy?

- How much, if at all, did the culture of lacrosse play a part in Love's demise?

This article appears in the May 2011 issue of The Washingtonian.