Illustration by Steve Brodner

On a Saturday this spring, Jim DeMint appears before a crowd in Manchester, New Hampshire, at an event called “A First in the Nation Freedom Forum.” The Republican senator from South Carolina gets three standing O’s—one just for stepping onstage. It’s at conservative gatherings like this, as well as back in his home state, that DeMint recharges after being inside the Beltway. He’s among his people.

“When I get discouraged in Washington, all I have to do is get out across America and talk to folks like you,” he says.

There couldn’t be a greater disconnect between the atmosphere in this room at Southern New Hampshire University and the reception DeMint gets in Washington. Depending on your perspective, the conservative lawmaker is either a brave champion for freedom or a bombastic showboater out for himself. He’s at once beloved by the grassroots Tea Party and immensely irritating to some of his Republican colleagues in the Senate.

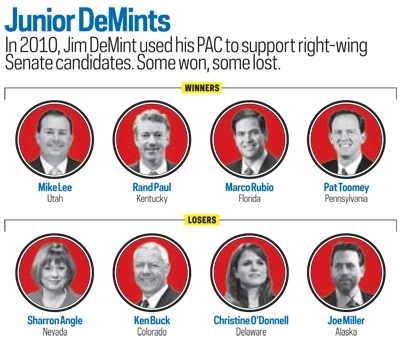

DeMint made waves in the 2010 Senate elections, bucking his party’s leadership by raising a lot of money for antiestablishment candidates who many in his party thought couldn’t win. Sometimes the doubters were right. Sometimes he was. He backed Joe Miller in Alaska, Ken Buck in Colorado, Sharron Angle in Nevada, and Christine O’Donnell in Delaware—all losers, some more embarrassing than others. Some think DeMint’s gambles on fringe candidates are part of the reason the GOP didn’t take the Senate. But DeMint also proved prescient in other races, helping fund such upstarts as Florida’s Marco Rubio, Pennsylvania’s Pat Toomey, and Kentucky’s Rand Paul.

Inside the Beltway, DeMint is seen as breaching protocol in an institution that has great respect for seniority and decorum. When criticized, he swipes back at his Republican colleagues, calling them “weak-kneed,” saying things like “I don’t want to be here six more years with the same people I’m here with now.” Needless to say, this doesn’t help.

Which raises a question: Is Jim DeMint the most hated Republican in the Senate?

Next: Will DeMint run for president?

“Least trusted,” clarifies a former Republican Senate leadership aide. In a club where everything turns on relationships and negotiation, that might actually be worse.

But here in Manchester, DeMint is beloved. A group of Republican presidential hopefuls are speechifying—Congresswoman Michele Bachmann of Minnesota, who delights the crowd of 350 with sharp jokes, and former Pennsylvania senator Rick Santorum, who today could put a teleprompter to sleep. Now here is DeMint—a.k.a. Senator Tea Party—and a man is crying, “Run, Jim, run!”

Will he? Through the spring, as the lackluster Republican field emerges, DeMint has seemed to go back and forth, stoking speculation with a trip to Iowa, then declaring himself uninterested, then opening the door by saying he’ll pray on it, then having those close to him say never mind, he didn’t mean it.

To the people in this room, Jim DeMint could be the future of the Republican Party, whether or not he runs for President. DeMint started an innovative political-action committee and in 2010 helped bring in a bunch of conservative new senators—Junior DeMints, some call them—to help him steer the country toward fiscal responsibility, limited government, and moral decency. Now he’s raising money to do it all over again and more in 2012. He says he has no choice.

DeMint could be the future of the Republican Party. He says he has no choice.

DeMint sees the state of the country in almost apocalyptic terms: debt, spending, a crumbling culture. “I think 2012 is our last chance to turn things around,” he says during an interview before his speech.

Onstage, DeMint paints himself as a whistleblower, standing up to leftward drifters in his own party. He tells the crowd about the time he says he watched an unnamed moderate Republican senator—Ohio’s George Voinovich, as it turns out—get his comeuppance when he was pressured by the “American people” to oppose President George W. Bush’s immigration-reform efforts. That’s your power, DeMint tells the crowd.

The stuff the audience loves is precisely the kind of talk that alienates fellow Republican senators. DeMint sells himself as an outsider in speeches and in his newest book, The Great American Awakening, which comes out in July. But at the beginning of each week, he goes back to Washington—and then he has to work with the very people he’s been publicly slamming. There’s only so much gossiping you can do behind coworkers’ backs before they stop wanting to sit next to you.

Next: DeMint is a love-hate kind of guy

The odd thing is, even those who don’t like Jim DeMint can’t help sorta liking him.

There’s his blustery public persona, and then there’s his decorous manner up close: He’s a fit, young 59, attractive and personable, quick to smile even when pondering the national debt crisis or criticizing the “false hope” of Barack Obama’s presidential campaign. He asks after children and self-deprecatingly reminisces about the counterculture moustache and “Afro” he sported in high school in the ’60s. People often describe him as reserved, the consummate Southern gentleman. One DeMint adviser says, “On a personal level, he is probably one of the most nonconfrontational guys you’ll ever meet.”

And yet. This is the senator who declared the stimulus package “a mugging” in a speech at the Heritage Foundation. This is the guy who sees little use for moderates in his own party, who announced in a Wall Street Journal op-ed, shortly after the November midterm elections, that Tea Party Republicans had been elected to “save the country—not be co-opted by the club,” so they’d best put on their “boxing gloves.”

If it were up to DeMint, there would be no Department of Education. Welfare would be phased out, and states, churches, and charities would take care of the poor. DeMint has advocated replacing income taxes with a flat tax or a national sales tax. He voted against George W. Bush’s Wall Street bailout (“One Giant Step toward Socialism” is how he headlined it in one of his books) and against President Obama’s stimulus bill, and he was one of only two senators to oppose Hillary Clinton’s confirmation as Secretary of State.

He has written several call-to-arms books, including 2009’s Saving Freedom: We Can Stop America’s Slide Into Socialism. In that book, DeMint uses “socialism” as shorthand for countless forms of government spending and blames it for Godlessness, immorality, irresponsibility, and laziness.

DeMint stresses that his Republican colleagues are "good people," just before ripping into them. He doesn't have a lot of friends in Washington these days.

In Manchester, during an interview in the university cafeteria, DeMint dismisses the idea of bipartisan compromise. Not now. The country is about to go “over a cliff,” he says, and the Democrats’ vision of “European collectivism” is speeding us toward that fall: “To go out now in this environment and say compromise and work with the other team—it’s like a coach telling players to go work with people who are trying to beat your head in.”

DeMint says that this kind of contentiousness didn’t come easily to him. As he tells it, he had to be dragged by his conscience into this fight. For at least a decade, he has been warning the country that the government is fostering a culture of dependence that could destroy the American way of life.

DeMint says that for his six years in the House, and after he was elected to the Senate in 2004, he tried closed-door persuasion, tried being nice. It didn’t work—his colleagues were too entrenched in a culture of spending and earmarks, in the “self-serving parochial interest that was bilking the federal government, draining it dry.” It was only after the 2006 election, DeMint says, when Republicans lost the Senate, that he realized the stakes were too high and his own party too far off course for him to remain silent.

DeMint often stresses that his Republican colleagues are “good people,” just before ripping into them. He describes many as “friends,” even though by most accounts he doesn’t have lots of friends in Washington these days. “Despite my friendships with a lot of them, despite the fact that they’re good people, they’ve completely lost sight of our constitutional responsibilities,” he says. “And so I set about to replace some of them. I made a lot of people mad.”

Next: DeMint's path to politics

Jim DeMint was raised in Greenville, South Carolina, where he and his wife, Debbie, his junior-high sweetheart, still live.

He was the second of four kids. His parents divorced when he was young. But he talks with fondness about the work ethic of his childhood, which seems to have informed the basic conservatism that blossomed later.

DeMint’s mother supported the family by starting the DeMint Academy of Dance and Decorum in their house. “No one owes you anything,” she would tell her kids. She installed a bell with a rope on a telephone pole and would ring it when she needed help at home. If there weren’t enough dance partners in his mom’s class, Jim, in his awkward preadolescence, would be summoned to dance with a high-school girl.

Later, his mother remarried and had two more children. DeMint had a paper route, bagged groceries, and played drums in a cover band, Salt & Pepper, which had black and white members. He went to college at the University of Tennessee, got an MBA at Clemson, and worked for his father-in-law’s advertising firm before starting his own marketing business. He and Debbie had four kids. A Presbyterian, DeMint has written that he had an awakening in his twenties after discovering a group of Christian businessmen who met weekly to discuss the Bible. In time, his understanding of Christianity formed the basis for his political philosophy: God gives freedom; the government takes it away.

He has lived for years with fellow lawmakers in the so-called C Street House on Capitol Hill, which is affiliated with a Christian organization called the Fellowship. “Politics only works when we’re realigned with our savior,” DeMint has said.

DeMint got involved with politics in the early ’90s when he advised another political newbie, Bob Inglis, on Inglis’s first run for Congress. Dave Woodard, a political-science professor at Clemson who was also advising Inglis, says the marketing man seemed to have a knack for assessing the political landscape. He recalls a small gathering in which DeMint “was the last person in the room to speak. And when he spoke, I remember thinking, ‘Wow, I should’ve shut up and listened.’ ”

"Politics only works when we are realigned with our savior."

Inglis won the race and term-limited himself. In 1998, he helped DeMint take over his seat, representing the fourth district of South Carolina.

During DeMint’s three terms in Congress and his first two years in the Senate, he was for the most part an uncontroversial team player. He was elected freshman-class president in 1998 and joined a team of lawmakers working to market the party better. He embraced the earmarks he would later spurn, albeit with some qualms. (“South Carolina is one of the poorest states, and I can’t sit on the sidelines and say, ‘You can give it out, but we’re not going to take it,’ ” he told the Greenville News in 2000.) Years before he would oppose President Bush’s immigration-reform efforts and declare that Americans could no longer trust the Bush administration on the economy, DeMint filled out a 2002 newspaper questionnaire thus: “Most admired person: President George W. Bush. . . . Most unforgettable person: Jesus.”

You Might Also Like:

DeMint did, however, show signs of the stubbornness that sometimes gets him in trouble with party leaders, even as it speaks to his voters. Running for the Senate in 2004, he said during a debate that he believed gay people shouldn’t be permitted to teach in public schools. At first, the negative headlines seemed to catch the candidate off guard. But DeMint refused to back down, adding days later that this was nothing personal against gays, that he’d have said the same thing about an unwed pregnant woman.

In time, DeMint apologized, sort of, without backing away from the original sentiment: He said the issue wasn’t his to decide. But during his 2010 Senate race, he repeated his stance on gay and unwed pregnant teachers, apparently convinced that time would vindicate him, if it hadn’t already.

Still, the pre-2006 DeMint mostly toed the party line. In 1999, a local paper reported, even as then–South Carolina Republican congressman Mark Sanford was warning that Republicans weren’t doing enough to rein in spending, DeMint, as “cochairman of message development” was touting the accomplishments of the GOP-led House. The same year, another paper recounted his efforts to stop his party from “feuding,” saying Republicans needed to be united to elect a Republican President. Said DeMint: “It makes me a little angry when Republicans stand on the sideline and talk about the failures of the Republican Party.”

Next: DeMint starts to make trouble in the Senate

Then, 2006. Everything changed. The way DeMint tells it, the problem wasn’t only that the GOP lost the Senate—in great part, he believes, because Republicans had fallen far short of the promise of limited government—but also that there “was not one discussion about anything we might’ve done wrong,” he says in the Manchester cafeteria. “No ‘post-analysis,’ as we used to call it in marketing.”

DeMint started to make trouble. He was elected chairman of the GOP’s Senate Steering Committee, a group of conservatives that was founded by the late North Carolina senator Jesse Helms. DeMint began calling himself a “recovering earmarker,” arguing that the practice corrupted legislators and distracted them from more important business.And he began to use Senate rules to hold up bills he didn’t like. Because of the way the Senate works, one member can have a big impact on the business of the entire chamber if he or she is willing to say no a lot. “The Senate does so much business by unanimous consent, it just takes one senator to say, ‘I object,’ ” says Senate historian Donald A. Ritchie.

DeMint is not known for “being much engaged in the substance and detail of legislative work,” says Norman Ornstein, an American Enterprise Institute scholar who studies Congress. “One of the things that frustrates colleagues is when you’re not involved in the painstaking work of crafting legislation, of finding common ground, or of actually fine-tuning ways to make it work—and then you just show up at the last moment to blow it all up.”

Through 2007 and 2008, DeMint’s increasing willingness to broadcast his frustration led to the perception among some Senate insiders that his highest priority wasn’t passing legislation but enhancing his reputation. Republicans began to complain that he was picking fights with the wrong party and refusing to settle for partial victories rather than no victories at all.

DeMint is not known for "being much engaged in the substance and detail of legislative work."

In 2008, DeMint angered colleagues by forcing a procedural vote on Bush’s global AIDS treatment-and-prevention program on a Friday evening, well after many senators normally leave town. The bill was popular on both sides of the aisle; DeMint objected to the measure’s cost, among other things. But when time came for the vote, DeMint was nowhere to be found. Roll Call reported at the time that “normally mild-mannered” senator Blanche Lincoln, an Arkansas Democrat who’d been forced to buy new airline tickets to accommodate the late vote, walked up to Republican senator John Thune of South Dakota in a fury. “Dude, where the hell is DeMint?” she asked. “I’m trying to get my kids to camp.” DeMint had skipped the vote to attend a family wedding.

“There’s a lot of people who have been very, very unhappy with his nitpicking and his obstructionist” approach, says former Republican senator George Voinovich.

DeMint is sometimes compared unfavorably with Republican senator Tom Coburn of Oklahoma, an ideological ally who has also opposed earmarks and used holds to block what he sees as fiscally imprudent legislation. Coburn has maintained better relationships with his less conservative colleagues and is described by Senate staffers as more of a problem solver—laying out his objections to legislation and working to help pass bills when those objections can be resolved.

“A senator’s power in the Senate is largely derived from their relationships with other senators and other senators’ view of how much they can trust you,” says a GOP staffer who asks not to be named. “And in that respect, DeMint does not have a great deal of influence.”

But another interpretation of DeMint’s evolution is that he sensed a new way of getting things done—or undone. The tactics he honed in recent years are not about hushed conversations in the cloakroom but about eye-popping quotes in the press and provocative e-mail blasts to his supporters. He says he’s discovered that his colleagues respond to feeling the heat rather than seeing the light.

Next: A painful period in DeMint's life

In 2007, when DeMint and a handful of conservative Republicans came out against the immigration-reform compromise that President Bush and both parties were crafting, the South Carolina senator had a breakthrough. He realized that instead of trying to convince his colleagues that the bill amounted to “amnesty” because it would help illegal immigrants acquire legal status, he could take his argument directly to the people by way of talk radio and blogs. He helped incite voter anger and kill the bill.

“The telephone system in the capitol actually crashed,” DeMint says.

“Our phones lit up,” recalls a former Re-publican leadership aide who has been critical of DeMint. The “amnesty” incident was instructive, the aide says, because, well before the emergence of the Tea Party, it demonstrated that a vocal minority in the Senate could fire up the American public and thereby change the national conversation.

After the 2008 elections, DeMint challenged the Senate hierarchy by introducing a radical slate of rules changes for his Republican colleagues, including term limits for many leadership positions and for senators sitting on the powerful Appropriations Committee.

DeMint realized he could take his argument directly to the people by way of talk radio and blogs.

By this point, some of DeMint’s colleagues were sick of what they saw as his divisive and time-consuming tactics. DeMint writes in The Great American Awakening that during a meeting he was persuaded by other senators that one of his proposals was a bad idea and he attempted to withdraw it. But his colleagues wouldn’t let him back away. He had to stand in front of the room while a secret ballot revealed just how disliked his proposal was: 36 nays and only 5 yeas.

“The consensus was that they were really ridiculous ideas and that he needed to be taught a lesson,” recalls a staffer who attended that meeting. “It was clear he didn’t have much support, so the thought was let him do it—and then blast his ass.”

But DeMint has his own version of events like this one. He talks of being made to pay for speaking the truth, of being railroaded in the press by his Senate colleagues and needing to defend himself. He describes this period as “very painful,” characterized by a “constant effort by people to marginalize me.” At one point, he writes, when he was leading the weekly Senate Steering Committee lunches, only one colleague—former Nevada senator John Ensign—would sit next to him.

Does DeMint want to run for President next year? DeMint recently told the Hill that some people wanted him to run, and he couldn’t help but consider their wishes out of respect. Afterward, allies attempted to walk back his words. “He’s not going to run,” said someone familiar with the senator’s thinking. “It would literally take an act of God.”

DeMint has even suggested he won’t run for another Senate term in 2016. “I’m thinking of finishing my term and getting back to my country-music career,” he playfully demurs.

It’s possible DeMint’s goal is to be doing precisely what he’s doing now, and damn the consequences in Washington. His constituency isn’t the political elite or those influenced by it. It’s a swath of people who like him better the more he irritates the political establishment, a section of America nearly as disgusted with free-spending Republicans as it is with “socialist” Democrats. DeMint—who says that when he first started in advertising he had to teach himself to craft the emotional appeals that consumers (and voters) respond to—has hit upon a winning message.

“He has done something that I think may be a new model, which is to wield power from the outside, not the inside,” says GOP pollster Kellyanne Conway, a DeMint admirer who describes him as “fearless and guileless.” Rabble-rousing may not garner DeMint the influence that would help him pass legislation, but it may shift the conversation within the Senate Republican conference a few inches to the right. And that in turn enhances his brand, allowing him to continue to make speeches and fundraise and back more “outsider” candidates. All of which shifts the Republican conference a little more to the right. “He’s the marketing guy,” says DeMint’s former state director, Luke Byars. “He knows sometimes you have to throw a bigger rock in the pond to get big waves.”

Next: The 2009 emergence of the Tea Party

If DeMint seems remarkably certain of himself despite the blowback he gets in his day job, if compromise is to him a dirty word, it may be because he sees this fight in grand terms. His tendency to see politics in a moral light means that he’s as quick to deflect blame from himself as he is to foist it on others. In front of certain audiences, he takes credit for being a provocateur; at other times, he presents himself as an innocent without a choice, pursuing his principles at great personal cost.

For instance, in 2009 he declared that Obama’s health-care legislation would be the President’s “Waterloo” (“If we’re able to stop Obama on this . . . it will break him”) and was criticized not just by Democrats but by his own party for it. But in The Great American Awakening, DeMint tries to deflect responsibility. “I only used Waterloo once on a conference call,” he writes—as if he didn’t know that senators making provocative statements tend to get quoted in the press. “It was Obama and his surrogates who made it a national issue.” After that, DeMint writes, there wasn’t much he could do—apologizing was impossible, and apparently so, too, was not using the term again: “I decided to use Waterloo as the battle cry for the freedom movement.”

In early 2009, as the Tea Party was emerging, DeMint found himself vindicated. For years he’d been trying to figure out where America was going and why, reading the likes of Austrian Friedrich Hayek on free-market economics. Suddenly, the themes he’d been talking about for years—socialism, a culture of dependence, the debt crisis—were the topics of angry protests across the country.

"I appointed myself as a spokesman for freedom-loving Americans."

“He saw it before anyone else did, but it was largely because the moment met the man rather than the other way around,” says a longtime DeMint adviser.

DeMint seized that moment. “I appointed myself as a spokesman for freedom-loving Americans,” he writes in The Great American Awakening.

Then later that year, Debbie DeMint was diagnosed with breast cancer and her husband considered not running for reelection. It was Christmas, they were home in South Carolina, and he put the decision in Debbie’s hands. She’d never been an eager politician’s wife. But everywhere they went, people thanked DeMint for his reform efforts—and thanked Debbie, too. Debbie, who would later endure surgery and radiation before being declared cancer-free, surprised DeMint by urging him to run again. They prayed for God’s help in the coming year, and as DeMint sees it, God answered that prayer emphatically.

In the interview in Manchester, DeMint suggests that during his 2010 campaign, “God gave us” Alvin Greene, his remarkably weak Democratic Senate opponent, so that DeMint could transfer nearly $2 million of no-longer-needed campaign funds to GOP state party organizations across the nation.

You Might Also Like:

DeMint founded his PAC, the Senate Conservatives Fund, in 2008. He says he got sick of making fundraising calls for the National Republican Senatorial Committee and hearing from donors angry about the state of the Republican Party. As DeMint saw it, they were right to be angry.

The Senate Conservatives Fund would be different from the NRSC. It would support only conservative candidates, even in states where the powerful NRSC thought a moderate had a better chance of winning. And unlike most senators’ leadership PACs, which give small, direct contributions to many politicians, the Senate Conservatives Fund would give heaps of money to a chosen few, with tactics borrowed from ideological PACs such as the Club for Growth and Emily’s List.

For the 2010 cycle, DeMint’s PAC raised $9.3 million. That’s not much compared with a machine like the NRSC, which raised more than $84 million, but it’s more than any other politician’s leadership PAC, according to the Center for Responsive Politics. DeMint’s anointed candidates benefited from hundreds of thousands of dollars—in one case, close to a million—raised for them or spent on their behalf by the Senate Conservatives Fund.

DeMint made his first big move in April 2009 with his decision to back Pat Toomey for the Senate over Arlen Specter in Pennsylvania. DeMint approached Specter, his sitting Republican colleague, to break the news. Then, as DeMint recalls, he attempted to soften the blow by adding, “I value your friendship.” Specter got up and walked away. “I’ve heard enough,” he said.

Specter was facing bad polls, and shortly after DeMint announced his support for Toomey, Specter switched parties. This chain of events and other moves by DeMint prompted a debate among Republicans that intensified as the election season wore on. Did it make sense to shear the party of moderates and place renewed emphasis on cutting taxes and spending, as DeMint and others argued? Or was it better to broaden the party’s tent—and potentially its appeal?

Next: DeMint and his fund's success pays off

And furthermore, wasn’t it naive to pretend that a Republican senator from a blue state like Pennsylvania should have the same platform as a senator from a red state like South Carolina? If electing only the most conservative Republicans meant being relegated to ever-smaller minorities, how could the party hope to have any impact or staying power?

“I would rather have 30 Republicans in the Senate who really believe in principles of limited government, free markets, free people, than to have 60 that don’t have a set of beliefs,” DeMint told the Washington Examiner.

“Some conservatives would rather lose than be seen as compromising on what they regard as inviolable principles,” Texas senator John Cornyn, the head of the NRSC, told the New York Times.

DeMint’s first gamble paid off. Specter the Democrat lost to his opponent in the primary, Representative Joe Sestak, who barely lost to Toomey in the general election.

DeMint and the Senate Conservatives Fund went on to endorse a number of long-shot candidates, including Marco Rubio, the young, charismatic former speaker of the Florida House of Representatives, who at one point trailed popular Florida governor Charlie Crist in polls by 30 points. Rubio’s come-from-behind victory got a boost from DeMint’s branding and from the Senate Conservatives Fund, which supported him to the tune of almost $590,000.

DeMint also backed winning insurgents in Utah (Mike Lee) and Kentucky (Rand Paul). In the Utah campaign, DeMint didn’t endorse Lee until after Republican incumbent Bob Bennett was eliminated at the state’s GOP nominating convention, leaving two Tea Party candidates to battle it out in a runoff. But DeMint cut an endorsement video for Lee ahead of time, to be shown once Bennett was out of the race. DeMint says he knew his colleagues would be “miffed” about this but felt he had no choice. Bennett was “a friend of mine,” but he wasn’t conservative enough and was going to be eliminated anyway.

As for Paul, DeMint backed him despite the fact that minority leader Mitch McConnell, the senior senator from Kentucky, endorsed secretary of state Trey Grayson. DeMint knew some might see his move as “an unforgivable act of insubordination,” he writes, but “[s]omething had to be done.”

"Murkowski's betrayal provides more proof that big-tent hypocrites don't really care about winning a majority for Republicans."

Not all of DeMint’s candidates worked out. In Colorado, DeMint endorsed Ken Buck over former lieutenant governor Jane Norton, who was considered the stronger candidate for the general election. Buck won the primary but lost the race to a Democrat, Michael Bennet. And a few of DeMint’s candidates were seen as so extreme or erratic that DeMint’s support for them shredded his credibility. In Nevada he endorsed Sharron Angle (famous for warning that frustrated voters might turn to “Second Amendment remedies”), and in Delaware he backed Christine O’Donnell, who—it was revealed during the campaign—had once come out against masturbation.

In the Alaska race, DeMint butted heads with another colleague. After losing the primary to Tea Partyer Joe Miller, Republican Lisa Murkowski launched a write-in campaign, prompting DeMint to release a fundraising e-mail on Miller’s behalf denouncing her. “Murkowski’s betrayal provides more proof that big-tent hypocrites don’t really care about winning a majority for Republicans,” he wrote. Murkowski managed to claw her way back to a seat despite DeMint’s considerable efforts for Miller, in the amount of $780,000.“The real question is, what’s his desire?” Murkowski told Politico after the elections. “Does he want to help the Republican majority, or is he on his own agenda, his own initiative?” She answered her own question: “I think he’s out for his own initiative.”

Some Republicans blame DeMint for lost seats, saying the party would be in a stronger position to retake the Senate in 2012 if not for his efforts. “We could have more Republican senators right now as a conference,” says Republican strategist Ron Bonjean, a former top Senate aide. “Trying to elect conservative Republicans in states where they’re unlikely to get past the primary is like chasing windmills.”

Next: DeMint's strange place in the future

Jim DeMint is in a strange place now, powerful outside the Senate and marginalized within it. In the wake of the 2010 elections, he won a legislative victory, forcing a ban on earmarks despite initial objections from McConnell and others.

A few months later, in the new Senate, DeMint jockeyed for a position on the Finance Committee. He lost, prompting some DeMint allies to suggest that McConnell might be purposely snubbing him.

But now there are more “outsider” senators in the Republican conference with DeMint, and the South Carolina senator says that together they’re changing the culture of the place. Utah’s Mike Lee, a constitutional lawyer who clerked for conservative Samuel Alito before he was appointed to the Supreme Court, says he hopes to take his cues from DeMint: “He is a firm believer, as am I, that from time to time you have to take a stand even when it’s unpopular and even when you know that others around you aren’t going to agree with you.”

DeMint has declared that he’ll raise $15 million for 2012. Now, when Republican candidates come to Washington to make the rounds, seeking to develop relationships and perhaps garner endorsements, the Senate Conservatives Fund’s Capitol Hill rowhouse is an important stop.

The endorsement of the senator "is like the Good Housekeeping seal of approval for conservatives."

The endorsement of the senator “is like the Good Housekeeping seal of approval for conservatives,” says Jennifer Duffy, who analyzes senate races for the Cook Political Report. “It legitimizes you as a candidate.” Already, says Matt Hoskins, spokesman for the Senate Conservatives Fund, about 30 Senate hopefuls have met with DeMint.

You Might Also Like:

Michael Steele Stumbles, Blunders, and Falls—Then Springs Back to Life

Next year is a presidential-election year, and there’s little doubt that the narrative of that race will overshadow everything else, including the GOP’s quest to retake the Senate. But assuming DeMint’s allies are correct about his unwillingness to launch a presidential run, that doesn’t mean his endorsements and his PAC can’t have an outsize impact. Any savvy Republican would be wise to heed the lessons of 2010 and its antiestablishment wave.

Not too long ago, Utah senator Orrin Hatch, who’s been reaching out to Tea Partyers in advance of what may be a tough reelection effort, said something that made him sound an awful lot like Jim DeMint. “I live for the day when we have 60 conservative Republicans in the Senate,” he told a newspaper.

The way DeMint tells it, the fate of the nation hangs on his colleagues’ seeing what he sees—that this is it, this is the moment.

There is a “great tension in America today,” DeMint says in Manchester, his soft voice belying the urgency of his words. “Are there enough Americans who are fiercely independent? Who really want to live free?”

This article appears in the July 2011 issue of The Washingtonian.