Portraits by Vincent Ricardel

Under the soft September moonlight, the Hummer stretch limousines lined up at an elementary-school parking lot in Laytonsville, Maryland. They were waiting to whisk 800 guests to the post-wedding party of makeup artist and eyebrow specialist Erwin Gomez and his partner, James Packard. As passengers stepped inside the limos, they saw television monitors that played a loop of national and local news clips of the couple—who had wed seven months earlier, in February 2004, in San Francisco.

The Hummers, outfitted with neon lights and stocked with full bars, wove through a residential neighborhood for ten minutes before parking in front of Gomez and Packard’s 8,000-square-foot mansion.

Outside, a tented stage showcased a drag-queen cabaret. A multi-tiered chocolate fountain anchored a dessert buffet next to the romantically lit back-yard pool. An Entertainment Tonight camera crew circulated among socialites, clients, and notables including Fox 5’s Sue Palka, Latin/Mexican singer Jimena, and Saudi princess Reema bint Bandar al-Saud. (As a former Gomez client, I attended the party.)

Media outlets such as the New York Daily News had pounced on the story that Gomez had invited Barbara and Jenna Bush—Gomez clients—during an election year. At the party, rumors spread that the gunmetal-gray Hummer parked on the front lawn and adorned with a large red bow was a gift from the absent twins.

The reception was meant to be the crowning event in a publicity blitz to celebrate Packard and Gomez’s status as a poster couple for gay marriage, a role they had assumed since the Washington Post featured them in a front-page article about their union.

Except that it was a sham.

At least that’s how Gomez now describes the wedding: “James thought getting married would be a good stunt—and obviously it worked, because we got so much publicity.”

But the relationship was rocky and both men had already cheated on each other. The Hummer “gift” was Packard’s idea, Gomez says; Packard bought the car, then hinted to guests that the Bush twins had delivered the present.

When San Francisco mayor Gavin Newsom legalized gay marriage, Packard had convinced Gomez to get on the next flight there. They were the ninth pair married at San Francisco City Hall. “James wanted us to be one of the first gay weddings,” Gomez says. “In the back of my mind, I thought this was going to help our relationship be stronger. I was thinking it will help our gay community to be recognized. That’s why I had to pretend I was still in love.”

Gomez says he kept up the facade—through scandals, lawsuits, murder threats, and the rise and fall of his Georgetown salon—until late last year, when he walked out of the building that bore his name.

Next: “I got taken advantage of.”

Gomez, 46, speaks softly, curled up on a chair with his two teacup-poodle puppies in his Dupont Circle one-bedroom apartment, a far cry from the eight-bedroom Laytonsville home that’s now in foreclosure. The feel here is not so different from his salon; house music thwomps gently in the background, kiwi and pomegranate soy candles flicker, a pewter tray with handles shaped like dragons—the salon’s Filipino-inspired symbol—holds bowls of jellybeans and chocolate-covered raisins. The decor is modern and warm, with an Asian edge. “I like it really warm because I have a warm heart,” Gomez somehow manages to say without sounding insincere.

Clients come and go, settling at the waxing station and makeup table two feet from the kitchen. His work remains steady—he shapes brows for about 20 clients a day and does about 20 makeup jobs a week. On occasion, he does makeup for guests on CBS’s The Early Show.

But much has changed since the days when he did actress Eva Longoria’s makeup at an awards ceremony and oversaw the makeup and hair for luminaries such as Vice President and Mrs. Biden and singer Tim McGraw for the Oprah show filmed at the Kennedy Center to commemorate President Obama’s inauguration. He also made up Obama’s sister-in-law, Kelly Robinson, in the Lincoln Bedroom on Inauguration Day. While waiting for Robinson, Gomez says, he introduced himself to Michelle Obama and massaged the future First Lady’s hands.

In July, Gomez filed for bankruptcy. His salon is closed and its building is for sale. His personal properties are either in foreclosure or tied up in litigation, and Packard—who he says nearly destroyed his life—has disappeared.

A few companies have offered Gomez opportunities—including the TV network Animal Planet, which approached him about being a guest on a reality fishing show—but Gomez declined the offers. “I have to figure out how I’m going to survive, and first I have to focus on happiness and on retaining my clientele,” he says. “I truly believe things are going to fall into place. I’ve done everything right, and I’m not worried about karma. I got taken advantage of.”

“I have to figure out how I’m going to survive. I’ve done everything right, and I’m not worried about karma.”

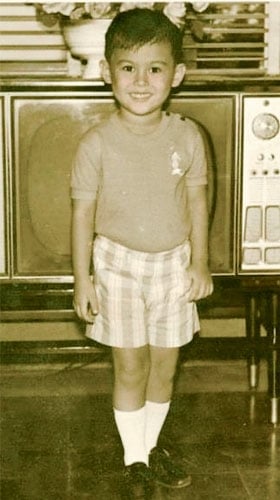

Gomez has always been ambitious and driven, says his mother, Teresita Gomez. Their conservative Catholic family moved from the Philippines to Orange County, California, when Gomez was nine. While he threw himself into after-school activities—volleyball, choir, cross country—at home he spent hours drawing. His favorite muse? Wonder Woman. When Gomez did actress Lynda Carter’s makeup in the late 1980s, he was too nervous to tell her she had inspired his career.

At 15, Gomez asked then–fashion photographer Farzad Kasrabod, after seeing his work in a magazine, for help breaking into the business. Gomez began assisting Kasrabod with makeup, styling, and photography.

“He was just a natural,” Kasrabod says. “He started doing makeup, and models would hire him. I would recommend him to art directors and boutique owners, and he started getting noticed.” Kasrabod was most impressed by Gomez’s people skills: “He would become your friend, like he’s known you forever. He won everybody’s heart.”

A year later, Gomez walked up to the Chanel counter at a department store in Costa Mesa, California, and talked his way into a sales job. Gomez worked as a counter salesman every day after school while practicing makeup on his friends at home. Six months later, Chanel promoted him to makeup artist.

After two years at Chanel, Gomez attended Saddleback College in Mission Viejo, California, where at his parents’ behest he studied nursing in addition to fashion. On the side, he bounced among various Orange County salons, working as a makeup artist and receptionist.

His father, a pharmaceutical representative, and his mother, a post-office supervisor, didn’t support Gomez’s aspirations at first.

“I came from a very strict Spanish-Filipino family,” he says. “It was hard enough for me to come out—they weren’t familiar with homosexuality, they weren’t familiar with someone who was an artist. They imagined the fashion business as drugs, sex, and rock and roll.”

In Gomez’s early twenties, his partially deaf boyfriend moved to Washington to attend Gallaudet University and Gomez followed him. The relationship ended, but Gomez stayed.

After stints with Prescriptives and Yves Saint Laurent, Gomez landed at the Elizabeth Arden Red Door Spa in Chevy Chase DC. Sharilyn Abbajay, who hired Gomez in 1994, was looking for someone to help her rebuild the makeup and retail business’s brand; Elizabeth Arden then had a somewhat stodgy reputation.

“I can still see him coming up the stairs for the interview, and it was almost a gift from above,” Abbajay says. “He was cool, trendy, and he could still blend. He just had such a magic about him.”

Next: “No matter what happens, he rises above.”

As Red Door’s first national makeup artist, Gomez traveled to teach other makeup artists how to apply and sell products. He had one of the company’s highest client-retention rates.

Gomez developed a signature cosmetic style that he describes as “timeless and classic, flawless glamour, and all about the eyes.” Clients say Gomez has a unique ability to make the eyes “pop.”

Many consider him a friend. Elise Lefkowitz scheduled Gomez regularly to put makeup on her housebound mother, Estelle Gelman, who endowed George Washington University’s Gelman Library.

“He was always there for us,” Lefkowitz says. “The day of the funeral, I didn’t want the funeral people to do her makeup, so he came and did it for her. That’s a true, true friend. And he brought someone to do her hair. For free. I can’t count anybody closer to me than that.”

Gomez donates his services and expertise to several charities, including the Hispanic Heritage Foundation. Several times a year, he meets with youth involved with the foundation to teach them about careers in the beauty industry. At the foundation’s annual awards ceremony, Gomez handles the makeup for all honorees, who in the past have included celebrities such as Antonio Banderas, Rachel Weisz, and America Ferrara.

“I tried to pay him, but he won’t take it,” says HHF president and CEO Antonio Tijerino. “He’s one of the greatest spirits I’ve ever come across in my life. No matter what happens, he rises above. And that is a really difficult thing to do, especially here in Washington.”

And yet when it comes to Gomez, to sift reality from embellishment is to negotiate a blurry web. Gomez will say he performs his services “on location,” but he does most of his work in his apartment. In June, he said he was going to do makeup for “the Captain America premiere.” In fact, Lanmark Technology Founder Lani Hay had hired him to do her makeup for a related event honoring Stan Lee and a Navy SEAL. Did Gomez meet Captain America star Chris Evans? Yes. Did he do makeup for any of the film’s actors? No.

Gomez often speaks about his humbleness, but his tiny bathroom is dominated by a three-by-two-foot poster of himself striking a pose for a charity campaign. His living-room walls are lined with 45 plaques he bought to display mentions in magazines such as Allure and Redbook. He can be both naive and savvy, genuine and cagey, humble and glamorous. He’s proud and passionate about his artistry but can at times seem similarly besotted with his name. As if to memorialize these contradictions, a tattoo scatters stars down his forearm, some colored in, some empty, “to represent my success and the holes where I fell.”

Soon after Gomez began working at Red Door in 1994, he met James Packard, dashing and confident, at a Rehoboth Beach party. At the time, Gomez says, Packard was running a Dupont Circle escort service. As the couple grew serious, Gomez asked Packard to give up the escort business.

Packard turned to a friend, millionaire John J. Warfield, who partnered with Packard to form J.J. Development, a real-estate company. Its first project was to restore the historic True Reformer building on U Street in DC.

Warfield, an investor and a Civil War buff, owned a railroad in Keokuk, Iowa, for a time before moving to Harpers Ferry. He bought trolleys from Philadelphia’s Main Line and restored them in Keokuk. During the great flood of 1993 along the Mississippi and Missouri rivers, Warfield put the trolleys on an existing track across a dam. For more than a month, the trolleys were the only connection across the river from the Quad Cities down to St. Louis.

“Hospital workers, factory workers—a lot of people would not have kept their jobs if not for John,” says Liz Clark, who was Warfield’s companion for 20 years. “And he ran those trolleys free, out of his own pocket.”

J.J. Development’s success convinced Gomez to open a salon with Packard, a dream he’d had for a long time. “John was a really good person, and the kind of person not about to get screwed,” Gomez says. “When he invested lots of money to be partners with James, it gave me more confidence—like, okay, I know you can do this.”

Next: No one knows the real James Packard

“James’s background has always been such a mystery,” says Morenike Abdullah, a friend of the couple’s who became the Erwin Gomez Salon & Spa’s general manager in 2008. She says he would tell people he was from the Packard automobile or Hewlett-Packard families, “but we knew it wasn’t true.”

It’s hard to find people to speak publicly about James Packard. His parents and sister declined to comment; neither an aunt nor longtime friends would speak on the record. Some sources had second thoughts after being interviewed and asked to be removed from this article. One claims to have witnessed Packard threaten to kill Gomez and himself. Multiple people were reluctant to talk about Packard for fear he would seek revenge. As one former employee says, “Even talking about him gives me the heebie-jeebies.”

Former friends guessed Packard was living in Florida with his friend Mary Ann Williamson, but she says she hasn’t seen him since February, and she sent a Facebook message saying: “There would be nothing that I would like better than to have James be able to tell the REAL story. I am not in a position to become involved in this mess. One day the truth will be able to come out. . . . He did not deserve what happened to him. Unfortunately, I have lost contact with him. I pray for him every day. He is a good person.”

“One day the truth will come out . . . He did not deserve what happened to him.”

Packard, 43, was adopted at birth and grew up in Frederick. He told friends he had a good relationship with his adoptive family and was especially close to his grandparents. He attended the Chelsea School in Silver Spring, a school for learning-disabled students. According to someone at the school, the unattributed quote beneath his senior-year photo reads, “Anxiety and distress interrupted occasionally by pleasure is the natural course of man’s existence.”

Packard attended Albertus Magnus College in New Haven. In the late 1990s, he found members of his biological family, including two aunts and an uncle, many of whom live in Virginia. His father and an uncle committed suicide before Packard had the chance to meet them.

In Washington, Packard gained a reputation as a partier who was plugged into various social scenes.

“James is eccentric, energetic, always enthusiastic, and excited about seeing different places and meeting new people,” says event planner Timur Tugberk, a Packard friend. “He’s a very driven and passionate individual. He gets emotionally invested in a lot of things, whether friendship or business.”

By some accounts, this emotional investment spilled into litigiousness. Packard has been in and out of court more than 20 times in Maryland alone, both as plaintiff and defendant. Among his targets: three neighbors, his former best friend, and his wedding planner.

By the time Gomez and Packard cut the Stella’s Bakery cake at their six-figure wedding reception, Gomez had begun to fear for his safety. Packard had been diagnosed as bipolar, Gomez says, and his behavior was increasingly erratic.

One spring, Gomez, his mother, and Packard attended an Easter brunch at friend and client Colleen Walling’s home near Annapolis. Packard was “very loud and not very respectful,” Walling says. “Erwin got very embarrassed and took him out in the driveway and tried to calm him down.”

Packard, Gomez says, “accused me of putting too much salt on his egg and trying to kill him. He put my mother and me in his car and said he was going to kill us. He was driving really, really fast—at least 100 miles an hour—and wouldn’t let us out of the car. My mom was crying, I was crying, begging, ‘Please don’t put us in danger.’ ”

“He was out of his mind,” Teresita Gomez says. “I was praying. I didn’t know what to do. He was hallucinating.”

Eventually, Packard regained control of himself. He told Gomez he loved him and, crying, let Gomez and his mother out of the car in a field in Frederick.

In 2005, Gomez gave Red Door management several months’ notice that he planned to open his own salon in Georgetown. Hoping that Red Door would pay him more to stay, Gomez—who had worked at the Chevy Chase location for 12 years—allowed Packard to speak to executives on his behalf.

The salon balked. Red Door sued Gomez for breach of contract, among other counts, claiming that he and Packard (whom Red Door also sued) took client lists and employees from the salon. Gomez maintains that he already had his clients’ contact information and they had his. Hairstylist Valerie Carrasquillo left Red Door with Gomez as his salon’s first hire, but she says Gomez didn’t do anything wrong by offering her a job. She was such close friends with Gomez and Packard that she named them her son’s godparents. Eventually, Red Door, Gomez, and Packard came to an agreement.

Next: Gomez begins to fear for his safety

James Packard and Erwin Gomez were the ninth pair married at San Francisco’s city hall after the mayor legalized gay marriage. Photograph of wedding by Kimberly White/Newscom

By the time Gomez and Packard cut the Stella’s Bakery cake at their six-figure wedding reception, Gomez had begun to fear for his safety. Packard had been diagnosed as bipolar, Gomez says, and his behavior was increasingly erratic.

One spring, Gomez, his mother, and Packard attended an Easter brunch at friend and client Colleen Walling’s home near Annapolis. Packard was “very loud and not very respectful,” Walling says. “Erwin got very embarrassed and took him out in the driveway and tried to calm him down.”

Packard, Gomez says, “accused me of putting too much salt on his egg and trying to kill him. He put my mother and me in his car and said he was going to kill us. He was driving really, really fast—at least 100 miles an hour—and wouldn’t let us out of the car. My mom was crying, I was crying, begging, ‘Please don’t put us in danger.’ ”

“He was out of his mind,” Teresita Gomez says. “I was praying. I didn’t know what to do. He was hallucinating.”

Eventually, Packard regained control of himself. He told Gomez he loved him and, crying, let Gomez and his mother out of the car in a field in Frederick.

In 2005, Gomez gave Red Door management several months’ notice that he planned to open his own salon in Georgetown. Hoping that Red Door would pay him more to stay, Gomez—who had worked at the Chevy Chase location for 12 years—allowed Packard to speak to executives on his behalf.

The salon balked. Red Door sued Gomez for breach of contract, among other counts, claiming that he and Packard (whom Red Door also sued) took client lists and employees from the salon. Gomez maintains that he already had his clients’ contact information and they had his. Hairstylist Valerie Carrasquillo left Red Door with Gomez as his salon’s first hire, but she says Gomez didn’t do anything wrong by offering her a job. She was such close friends with Gomez and Packard that she named them her son’s godparents. Eventually, Red Door, Gomez, and Packard came to an agreement.

In the midst of the battle with Red Door, Packard presented Gomez with an operating agreement for the company that was to own the Erwin Gomez Salon & Spa. Packard had convinced Warfield to buy a Wisconsin Avenue building for the salon. According to salon documents, Warfield contributed an additional $232,500, Packard put up $223,200, and Gomez $9,300. Warfield’s involvement was a favor to Packard, says Warfield’s former companion, Liz Clark: “The salon was an offbeat venture for John. He was generous, but he was not into private ventures. He was into community-building.”

The partners enlisted business consultant Sab Shad to craft a business plan. She had managed spas in the UK before becoming regional vice president at Red Door. Shad and Gomez secured a $2-million Small Business Administration loan for minority-owned ventures. Packard structured the company so that he retained 51 percent ownership to Gomez’s 49 percent.

Gomez says he didn’t read the contract before signing—he was rattled by the Red Door suit and just wanted to move on with his life. Packard convinced him that as creative director, Gomez shouldn’t be paid because he hadn’t invested as much in the salon as Packard had.

Shad didn’t become aware of the details of the operating agreement until spring 2010. Not until then did Gomez and Shad learn that the contract ensured that if Gomez left the company, “he would be worth nothing,” Shad says.

For years, friends say, Gomez was happy to leave the finances to Packard so he could focus on his work. “James was the driving force in terms of business, and with that goes a certain character,” says Kasrabod, the former fashion photographer. “But where do you draw the line? It’s like saying, ‘I want to have an alligator for a pet. I’m going to keep him in my tub, and I’ll expect him not to bite me.’ I always felt that James’s aggressiveness would spill over sooner or later.”

Next: Celebrities descend on Gomez’s salon

The salon opened in December 2005, and within months celebrities such as singers Stevie Wonder, Keyshia Cole, and Jennifer Holliday; soccer star Mia Hamm; and actresses Dania Ramirez and Rosario Dawson were stopping by. One day after closing, Maria Shriver walked in without an appointment because, says Adrian Avila, who did her makeup and lashes, “she had heard about the salon and wanted to experience it.” In its first year, the business brought in more than $1.3 million in revenue.

The salon entered national and international competitions and won a Wella International Trend Vision Award for hairstyling, the Olympic gold medal of the salon industry. Hollywood hairstylist Oribe Canales, whose products Gomez carried, worked with Gomez on a photo shoot at the salon. “He holds up to any makeup artist I’ve worked with,” Canales says, “and I have worked with everyone.”

Many Washington elite left Red Door to follow Gomez, including Gilman Group vice chairman Georgia Gilman, wife of former New York congressman Benjamin Gilman.

“The whole congressional community, the Stephanopouloses, the embassies—people were just supportive of him,” Gilman says. “There are other nice, classy salons, but they don’t have the personal touch that Erwin gave you.”

Gomez worked long hours, sometimes attending to 40 to 60 clients a day, often without taking breaks to eat. Even when Gomez was fully booked, “people were just walking in to see him without appointments,” says makeup artist Adrian Avila. “The front desk would tell them he’s got no availability. They would call him directly on their phone, he’d be in there doing someone’s makeup and agree to it. ‘No’ is not really in his vocabulary when it comes to business.”

Staffers say Gomez was more like a friend than a boss. “He’s just the sweetest guy in the whole wide world,” hairstylist Peggy Ioakim says. “You see him working hard, you want to work hard, too. Every day I couldn’t wait to put on my high heels, put my makeup on, and go to work. I felt like a rock star. I’ve never had such a fun time in my career, even when I owned my own salon.”

Meanwhile, Packard bought designer clothes, luxury trips, and a Salvador Dalí painting, Gomez says. Packard bought company cars: for himself, a Bentley and a Rolls-Royce Phantom, for Gomez a $100,000 BMW convertible.

In 2007, as the salon expanded into a larger space, Gomez broke up with Packard. “I wanted to leave him since the episode in the car, but I loved him and I knew that he loved me very much,” Gomez says. After Packard’s bipolar diagnosis, Gomez says, he worried that Packard would kill himself if Gomez left him. Later, Gomez started to fear for his own life.

Abdullah, who socialized with the couple, says Packard had two sides: “There were a lot of good things about James. He really was a lot of fun to go out with. And he was also very good to Erwin on many occasions. But he craved the limelight so much. He was always trying to be someone else.”

Despite the split, Packard and Gomez continued to live together in a $1.5-million Bethesda house. (They rented out the Laytonsville home so Gomez would have a shorter commute.) Gomez says Packard insisted they keep the breakup a secret, even from their staff.

Life at home grew awkward, though, and by February 2009 Gomez had had enough. Gomez’s close friend Sherie Gabriel, a real-estate agent, went to the house to gather Gomez’s things. She says Packard followed her from room to room, threatening to call the police.

“He was saying, ‘This is company property,’ ” Gabriel says. “When I took Erwin’s pillow, James was ranting, ‘This is ridiculous. I own him.’ He said to Erwin, ‘I own you, and I own the Erwin Gomez Salon.’ That burned Erwin so bad. I went to his first lawyer’s meeting with him, and the first thing on his list for the lawyer was ‘I want my name back.’ ”

Gomez moved in for a year with Lani Hay. “It was wonderful,” Hay says. “I would come from work, and dinner would be made and we’d watch Dancing With the Stars or Glee. He was a workaholic, but he really likes to cook and I don’t cook at all, so it was perfect.”

But Hay says she had to install surveillance cameras. The first week after Gomez moved in, someone flattened the tires on Hay’s and Gomez’s cars. A few weeks later, the tires were missing from the BMW Gomez drove. One day when Gomez was out of town, the car disappeared. The police told Hay that Packard had ordered it towed from her house.

The salon’s fame grew in the fall of 2009 when Michaele Salahi and a Real Housewives of D.C. camera crew visited for makeup and hairstyling before she and her husband crashed a White House state dinner. The incident garnered Gomez and hairstylist Peggy Ioakim a cameo on the show, national media attention, and a federal grand-jury summons.

Salahi says she felt betrayed by statements Gomez made to the press. “Erwin’s comments about me were shocking and hurtful—I had never seen that side of him,” she says. She points to a Modernsalon.com article saying that Salahi “rarely paid her bill” for Gomez’s services and got hair extensions from Ioakim. “For this preparation I made her leave a deposit,” Gomez told the Web site. “She did end up paying after my salon manager chased her down as she was leaving for the White House. . . . She is so bubbly and charming. It’s hard to judge someone’s character and it’s hard to hate her. But this is really crossing a line.”

Salahi calls such statements “really too painful for me to relive. I was never asked for a deposit, never chased—good grief. The salon, as he states, did not do extensions.”

Next: Packard’s personality goes to the extreme

Staffers at Gomez’s salon say he worked long hours and was more like a friend than a boss. Photograph courtesy of Gomez

Gomez, Ioakim, and Packard arrived at US District Court for the grand-jury hearing in a white Hummer stretch limo. Packard “asked us to look very Hollywood,” Ioakim says. “For me, it was a lot of eye-rolling. I didn’t realize we were going to have all these cameras there. It was silly.” Gomez says he was mortified but didn’t want a confrontation with his ex.

Later, Packard would pay $7,000 at auction for the red sari that Salahi wore to the White House, a gesture Salahi says moved her to tears. By then, however, she had already forgiven Packard after he approached her at a Georgetown event and apologized.

“He said, ‘We had to create the drama, and that’s how it has to roll. My business went up 200 percent,’ ” Salahi says. “It was awesome that he recognized it and said, ‘I’m sorry, Michaele, I love you,’ and even more loving that he purchased the dress. To me, that was the biggest love he could have given back.” She remains angry with Gomez, however.

Packard spread negative press about the Salahis only because “he saw that as part of his job, marketing the business,” says friend Howard Cromwell, who frequently partied with him on the K Street and Georgetown social scenes. “But he’s a sweetheart. He’s a fun, happy-go-lucky guy who keeps the party going.”

If Packard’s goal was to get his salon on the map, he succeeded. “He made things happen,” says makeup artist Kari Slansky, a Gomez protégé. “James had a vision and was putting it into place.”

But starting in 2007, friends say, Packard’s personality changed. He became “manipulative, controlling, and eccentric, which outweighed his business sense,” Slansky says.

David Rahnemoon was friends with Packard until that year, when Packard and Gomez threw a fundraiser in the salon’s back yard. The Washington Post’s Reliable Source column reported that neighbors complained about noise; threw glass, rocks, and bricks into the party; then beat up Packard when he climbed into their yard. After a second fight in front of the neighbors’ house, Packard went to the hospital, and two neighbors and Rahnemoon were arrested for assault.

Rahnemoon, who claims he only grabbed the wrist of a man who was trying to hit Gomez, says he lost his job because of the incident even though he was cleared of all charges. Several months later, he says, Packard admitted he instigated the altercation by tossing a drink in a neighbor’s face. “I started that whole thing,” Rahnemoon says he told him.

“He ruined my life, my career,” Rahnemoon says. “When reporters called, instead of trying to prove my innocence, he spun it so he would get publicity.”

The Reliable Source piece noted that Packard’s $4,000 Dolce & Gabbana suit was ruined.

In 2010, Gomez confronted Packard, charging that he was using company money to fund his luxurious lifestyle. Gomez says Packard responded by accusing him of stealing from the salon and asking employees if they had seen Gomez taking money out of the register.

Gomez says that Packard—who had set up Gomez’s personal and professional Facebook accounts—began posting status updates, pretending to be Gomez. “I LOVE JAMES SO MUCH TONIGHT I WANT THE WORLD TO KNOW!” one read, soon after he changed Gomez’s relationship status from single to engaged. Another misleading post, accompanying a photo of a baby, announced, “to be honest we got word that babie [sic] MeiLei arrives this month.”

In the salon, the ambience changed whenever Packard walked in, employees say. “You know in Harry Potter the big black things that flew around? The dementors. That was the atmosphere,” Avila says. “Everything went cold. It was hard to put on a happy face for the guests.”

Last year, Gomez finally read the operating agreement for the salon and showed it to Shad. “I was shocked,” Gomez says. “He structured the contract so that I could never escape.” The agreement contained a non-compete clause that made it virtually impossible for Gomez to leave the company. He would owe Packard millions if he did.

Whenever Packard walked into the salon, “everything went cold. It was hard to put on a happy face for the guests.”

At the salon one day, Gomez and Avila were startled when a small Sony recorder fell from behind a mirror in Gomez’s makeup room. Further investigation revealed a handful of recorders around the salon, Velcroed behind mirrors, including in the salon office, to which only Gomez, Shad, Abdullah, and Packard had keys.

That spring, Gomez stopped talking to Packard, who refused to give the salon money for operating expenses when he wasn’t there. The business couldn’t bring in suppliers or pay vendors on time.

Staffers say that Packard’s lawyer, Stephen O’Connor, spent time in the salon to assess the situation, then advised Packard to stay away. (O’Connor declined to comment without his client’s consent.) When O’Connor suggested that Gomez take charge of the day-to-day operations, Gomez asked him to speak to the staff on Packard’s behalf.

After the meeting, Gomez exploded at his friend and employee Valerie Carrasquillo for not speaking up in support of him. She says that while she agreed with the change, she didn’t see the point in criticizing Packard to his lawyer, because the lawyer was working for Packard.

“He called me into his little room and said, ‘Who the hell do you think you are? How dare you not represent for me?’ I had never seen Erwin go crazy like that. He threw a product at me,” she says, crying as she recounts the incident. “He was my kid’s godfather.”

“I just lost it,” Gomez admits. “And I never lost it like that before in my life. She knew more than anybody I was about to lose my business. James planted in my head that I would ruin people’s lives if I were ever to leave, and I had 40 people who I would disappoint.”

Two days later, Shad and Abdullah called Carrasquillo in for a meeting.

“They said, ‘What happened on Tuesday did not happen—you’re not to say anything about it to anybody. And you have to apologize to Erwin for putting him in the situation that he did that to you,’ ” Carrasquillo recalls. Instead, she packed her things, walked around the corner to Salon L’eau, and began working there the next day.

Carrasquillo’s final paycheck, which was supposed to cover two weeks, was for $14.84. “I framed it,” she says. “It’s in my house as a reminder of what I’ve accomplished in my life since then, and I will never look back.” (The salon maintained that Carrasquillo owed the salon money, which was taken out of the check.)

Now Carrasquillo—who is no longer in touch with Gomez or Packard—believes that Gomez acted that way toward her “because the business was going downhill and he knew the only way I would leave would be if he treated me like a piece of shit. In my heart, I want to believe that,” she says. “For the years I knew them, Erwin was a great person. I know James has some black cloud following him, but not when he was with me.”

In the fall of 2010, Gomez enlisted a lawyer to help him try to buy Packard out of the salon, but Packard refused. At 3 in the morning one day in October, Packard e-mailed Gomez and said he was fired, then negotiated with Gomez’s lawyer two days later for him to return to work. The temporary firing turned out to be fortuitous for Gomez because it let him out of his contract. Otherwise he couldn’t have left the company without paying Packard hefty penalties.

What goes around, comes around

On a chilly evening in November 2010, after his last client left the building, Gomez took one final look at the salon he had designed: the cherry-wood panels that curved like a dragon tail, his $17,000 Takara Belmont makeup chair, the windows that fogged for clients’ privacy, his name in the window. He whispered goodbye to the dream he had built and walked out. Within days, most of the staff followed.

Packard emptied the salon’s bank accounts as well as a joint account he held with Gomez. He posted a video on Facebook showing the frozen bodies of the couple’s two dead dogs, in which he said, “You are one cruel person, Erwin Gomez.” (Gomez says he had gotten the frozen bodies from the vet because Packard had wanted them cremated.) Packard tried to sell the BMW on eBay, asking $6 million for the car driven by a “celebrity makeup artist.” He ended up returning the car to the Rockville dealership, which called Gomez because there was still money owed on the vehicle.

Packard’s friends say he felt demonized. “Erwin walked out and never came back,” Packard’s friend Howard Cromwell says. “James was the one who footed the money for Erwin Gomez while they were dating. Erwin gave his name, but it was pretty much James running the show.”

In December, Packard posted a note on his Facebook page about the salon: “After 14 years of being with someone and then hearing ‘I quit’ after investing over five plus million has really shaken the ground I walk on. . . . I have all intentions of keeping the salon together, but I can’t do it alone. It will take time and commitment from each and every one of you.”

The Erwin Gomez Salon & Spa closed in January. In February, Packard vanished. The building’s owner, John Warfield, died at age 62 in 2006. He had intended to rewrite his will, former companion Liz Clark says, because he left his entire estate to his father, who died five years earlier. As a result, the estate was to be divided among distant cousins he didn’t know well.

When the named executor of Warfield’s will didn’t wish to serve, Packard persuaded the Jefferson County, West Virginia, clerk to name him the personal representative of the estate. The county didn’t contact Warfield’s family for approval. To date, the family hasn’t received any of the millionaire’s money.

Jefferson County officials confirm that there’s an open warrant for Packard’s arrest. Charged in 2011 with embezzlement by fiduciary, Packard faces allegations that he misappropriated more than $3 million of estate assets.

“We’ll be able to find him sometime,” says Ed Buzek, Warfield’s cousin and one of his six heirs. Buzek says that in addition to the millions, Packard sold Warfield’s Harpers Ferry house and kept the money.

Packard’s friend Timur Tugberk expects that Packard will resurface: “After having something really hard happen—a very public breakup and a very public company breakup—you might think it’s best to pick up and start over or take a break. I think he was encouraged by close friends to get the hell away.” The last time Tugberk heard from Packard, in the spring of 2011, Packard said he was in Florida.

Which leaves Packard’s lawyers and creditors with unpaid bills, local sheriffs unable to extradite him, Gomez without the resources to pay the mortgages on their houses, the salon’s lease in default, and a lawsuit against both Gomez and Packard. Gomez is cooperating with the Warfield estate’s attempt to sell the salon building.

Though he has lost his houses, his car, and his salon, Gomez says he’s in a better place: “He can have it all. One thing I realized is that material things are not important to me. The most important thing is your happiness and your freedom, and no money could ever be able to pay that. I’m so grateful that my staff left, because James thought he could keep the name and the business. He owns the Erwin Gomez Salon & Spa, not Erwin Gomez.”

Friends aren’t surprised by Gomez’s optimism.

“I’ve never seen a person pushed so far down to the ground and then pull himself up by himself,” Elise Lefkowitz says. She notes that while Erwin didn’t receive any of the profits from the salon, he was still honoring gift certificates that were purchased before it closed. “That’s how trustworthy and above-board and what a super person he is.”

In August, investors including Kunal Shah and Vinoda Basnayake, who own DC’s Eden lounge, approached Gomez about opening a new salon at 24th and L streets in the District’s West End. As of press time, the business was scheduled to open in late spring 2012. Gomez envisions an ambience that is “very Zen, tranquil, very modern. And a very warm feeling that people are going to be so comfortable that they feel like they’re at home. This is going to represent the new me. And what my new me is all about is simple and good vibes.”

The name of the salon representing what he calls his “new me”? Karma by Erwin Gomez Beauty Lounge.

This article appears in the December 2011 issue of The Washingtonian.