Illustrations by Wesley Merritt

At the dawn of the 21st century, Hogan & Hartson and Howrey Simon Arnold & White—later shortened to Howrey—were among Washington’s biggest and most profitable law firms. They were located less than a block apart near DC’s Metro Center. Each employed hundreds of lawyers who made well into the six figures—and rainmakers at both firms took home more than a million dollars annually.

It took just a decade to transform both of them—a decade filled with fateful decisions, new leaders, and contrasting cultures as both firms attempted to adjust to the emerging 21st-century realities of the legal profession.

Only one of them survived.

While Washington’s venerable law firms seem steady, as permanent as the stone edifices lining DC’s streets, the truth is that they’ve turned into very big businesses that require leaders every bit as visionary as a Fortune 500 CEO, businesses that are as susceptible to the pressures of the global economy as any manufacturing plant in the Rust Belt.

Gone are the days when law-firm partner was a job as solid and tenured as college professor.

Just ask any of the lawyers at Howrey.

See Also:

The second floor of downtown DC’s Warner Building is eerily quiet. No footsteps echoing off the white marble floors, no ringing phones. Pieces of designer furniture are arranged into odd groupings. Each modern-looking couch and table is tagged with a yellow number indicating the item’s order on the auction block. The only voice comes from a large conference room down a hallway.

“This is a golden, golden opportunity,” the auctioneer tells the two dozen people gathered before him. The bidders are there to pick over the remains of Howrey.

At its peak, Howrey had $573 million in annual revenue, and on average its partners in Washington took home $1.3 million a year. But after 55 years in business, the firm dissolved in March—victim of a perfect storm of problems. The economy, ineffective management, overexpansion, risky investments, and bad luck all played roles in bringing down Howrey. Some of its former lawyers would add another reason: partners too quick to give up.

Now in Chapter 11 bankruptcy, the Howrey estate is holding the auction on this mid-August afternoon to help pay its debts and to clear out of the 300,000-plus square feet it rents in the Warner Building for $50,000 a day—at one time a reasonable expense. Entire rooms’ worth of furniture sell for as little as $10. One man whispers to the woman next to him that he just saw his own office furniture hit the block and it didn’t get a single bid.

As Howrey’s partners prepared to shutter their firm in March 2011, a neighboring Washington law firm was gearing up for a much different event.

Hogan Lovells, known as Hogan & Hartson prior to its 2010 transatlantic merger, held its first global-partners conference that month at the Gaylord National Hotel at National Harbor, just across the Wilson Bridge from Old Town Alexandria. The three-day affair was the first chance for the newly combined firm’s more than 800 partners to gather in one place since Hogan & Hartson’s union with the London-based law firm Lovells nine months earlier.

The schedule was packed with presentations by firm leaders. Practice groups strategized about ways to develop business.

During one of the three days, a ballroom was filled with more than 40 kiosks, each representing a different Hogan Lovells office. At the Northern Virginia station, the lawyers could sample Virginia peanuts and wine and learn about the local Fortune 500 companies, such as General Dynamics and Gannett, that supply the office with work. The event was intended to encourage partners to get to know one another—not easy at a firm that almost doubled in size overnight to 2,300 lawyers spread across the globe.

For the partners who knew Hogan & Hartson when it was a regional firm, the transformation into one of the world’s ten biggest law firms can be hard to grasp.

Ty Cobb, who started at Hogan in 1988 and is one of the firm’s star white-collar defenders, recalls an exchange he had with his daughter a few months after the merger with Lovells. She was studying abroad in Alicante, Spain, a Mediterranean port city. While on a run, she spotted the Hogan Lovells building. She called her dad to ask why he hadn’t mentioned that his firm had an office in Alicante.

“I had to confess,” says Cobb, “I didn’t know until she told me.”

Next: The world begins to change

To outsiders, Hogan & Hartson and Howrey may have had much in common, but their legal work differed.

Howrey was a litigation firm, meaning its attorneys specialized in doing battle in the courtroom. They were divided among three areas: intellectual property, antitrust, and a catchall practice called global litigation.

Hogan had a broader model. While it too had great litigators, it also had large corporate and regulatory practices.

The firms’ cultures contrasted as well. “Howrey had a history—a culture—of having a less consensus-driven partnership,” says law-firm consultant Peter Zeughauser, who worked with both firms and continues to consult for Hogan Lovells. “The history at Hogan & Hartson was very much about developing a sense of partnership and getting people to buy into that. At Howrey, it was much more top-down.”

For decades, those contrasting cultures had worked. Both had flourished, making generations of lawyers wealthy and developing client lists that read like a who’s who of American business. While the firms differed in size—Hogan & Hartson had 1,288 lawyers before it merged, and at its height Howrey had 750—both firms entered the 21st century with a growing global profile.

As the new millennium approached, the leaders of both Howrey and Hogan & Hartson were preparing to turn over control to the next generation—though neither firm realized how critical that handover would be.

The World Begins to Change

Howrey was founded in the summer of 1956 as Howrey, Simon, Baker, & Murchison—named for four lawyers who came together to establish the nation’s first antitrust firm. Taking top billing was former Federal Trade Commission chair Edward F. “Jack” Howrey.

Since 1983, Howrey had been guided by managing partner Ralph Savarese, who in the 1990s launched a national branding campaign around a tagline that reflected Howrey’s tough reputation as a firm of litigators: “In Court Every Day.”

Savarese, now a consultant in California, had been an effective—though not necessarily beloved—leader.

“Ralph was careful never to have close personal friends in the firm about whom he could not make an adverse decision if he had to,” says John Briggs, who practiced at Howrey from 1973 until 2008 and served in management roles there for 20 years. “He could be close to people, but he could fire anyone. If things went south, he wasn’t going to be blinded by personal friendships.”

During his 17 years running the firm, Savarese dramatically changed the footprint of Howrey. He opened the first office outside the Beltway, in Los Angeles, in the early ’90s and expanded the antitrust firm into other specialties.

He also initiated two key combinations that his successor would help finalize. The first was a merger with the intellectual-property firm Arnold, White & Durkee, which gave Howrey a stronghold in that type of work. The second was the acquisition of a large group of antitrust lawyers from Collier, Shannon, Rill & Scott, including one of that firm’s name partners, James Rill.

The firm’s third category of work, global litigation, encompassed a hodgepodge of more than a dozen litigation specialties that evolved as the firm became larger.

Though there wasn’t a clear answer as to who should replace him, by 1998 Savarese was ready to retire.

Howrey’s executive committee—the six-partner group that helped run the firm—selected Robert Ruyak as the firm’s managing partner designate in 1998. He would spend the next two years making the transition into the role, taking over from Savarese as leader in 2000.

Ruyak had joined Howrey in 1976. He was one of the firm’s strongest trial lawyers and had been involved in management as a member of the executive committee for ten years. But he was far from the only contender to succeed Savarese. John Briggs was another frontrunner. Partners Mark Wegener and Los Angeles–based Tom Nolan were also widely respected and were viewed by some as managing-partner material.

Ruyak looked the part. One of his former partners remarked that, with his silver hair and sharp suits, he looked like a managing partner out of central casting. He was described by colleagues and the press as “a visionary.” But what Ruyak lacked, say some former partners, was a solid understanding of the business of the firm. He hadn’t come from a business background. Before getting his law degree at Georgetown, he studied political science at Gannon University in Erie, Pennsylvania.

For Howrey, Ruyak imagined a future as the preeminent firm in all three of its core practices. He was committed to Howrey’s global expansion and to building a large-scale intellectual-property practice in Europe. He had vision—but his ability to execute it would come under harsh scrutiny.

Next: The most difficult decade for the legal industry

Hogan & Hartson is Washington’s oldest major law firm, founded during Teddy Roosevelt’s first term as President in 1904 by attorney Frank J. Hogan, who was joined two decades later by onetime IRS lawyer Nelson T. Hartson. Hogan became known as one of the nation’s greatest trial lawyers, successfully defending oil magnate Edward L. Doheny in the Teapot Dome scandal. Over the next decades, Hogan & Hartson developed deep ties to the local community, and in the 1970s it was the first major law firm to establish a standalone pro bono practice.

When Hogan & Hartson’s longtime managing partner Bob Odle decided to step down in 2000, there was no question about who the most powerful person at the firm was. Since joining Hogan in 1979, J. Warren Gorrell Jr. had established himself as the hardest-working lawyer there—and its biggest rainmaker.

“He was beginning to develop his own clients as an associate, which is extremely unusual,” recalls Hogan partner Janet McDavid. “I don’t think Warren needs as much sleep as most of us.”

Gorrell built a corporate practice advising major corporations on mergers, acquisitions, and other transactions. He also carved out a niche as the go-to lawyer for real-estate-investment trusts, or REITs, which would become a big part of the economic recession years later.

He took some hard-earned time off in the summer of 2000 to travel with his family through Africa and Italy. When he returned, Odle, who had managed Hogan & Hartson since the year Gorrell joined it, approached him about leading the firm.

“Warren was my number-one choice, as he was for many others,” says Odle.

Under Odle, Hogan & Hartson had begun its own international expansion, opening offices in nine international markets. Gorrell had served three terms on the five-member executive committee, so he had been closely involved in developing the firm’s strategy.

But heading Hogan wasn’t a job Gorrell was after. “I spent a fair bit of time trying to talk the executive committee and Bob out of the idea,” he says.

Odle had sacrificed having an active law practice to manage the firm full-time. That move concerned Gorrell, who wasn’t willing to give up his client work. The firm also couldn’t afford for Gorrell to stop practicing—his work typically brought in more revenue than that of any other partner.

For Gorrell to take the job, Hogan & Hartson’s management structure would have to be overhauled. A compromise was reached to install Gorrell as the firm leader with a new group of senior managers to help him run various pieces of the business, freeing up Gorrell’s time for clients.

To reflect the differences in the role, the head of the firm would no longer be called managing partner. Gorrell became Hogan & Hartson’s first chairman in 2001. Odle would later say that one of his greatest achievements had been convincing Gorrell to take over.

Allies and Power

With their new leaders in place, Hogan & Hartson and Howrey embarked on the decade that would prove to be the most difficult for the legal industry.

During the preceding years, some major firms had begun expansion both nationally and overseas. Hogan & Hartson opened its first office outside the Washington area in 1988 in Baltimore. In 1990, the firm set up shop in London. Howrey reached beyond the Beltway in 1992, when it opened in Los Angeles. The first decade of the 21st century saw globalization accelerate that trend.

Large law firms are generally run in similar ways. Equity partners are required to invest money in the business and are thus owners of the firm. Though partners have to make capital contributions, they share in the firm’s profits at the end of the fiscal year. The size of a partner’s share is determined by the amount of business that person is responsible for bringing into the firm, among other factors.

The degree of authority partners have varies from one firm to another. At Hogan & Hartson, they played a larger role in selecting firm leaders than they did at Howrey. Large firms have at least one subset of partners, often called a management or executive committee, who are responsible for governance. These groups are typically responsible for setting strategy and helping the firm leader with management responsibilities.

At Hogan & Hartson, each member of the executive committee had to be elected by the full partnership. At Howrey, a slate of preselected candidates was presented by firm leadership to the full partnership for an up-or-down vote, thus limiting the power of partners to choose who governed them.

And that wasn’t the only difference in governance between Hogan & Hartson and Howrey. Hogan’s new management structure gave Gorrell a lot of support. A senior-management group of six managing partners handled daily administrative responsibilities. The executive committee was still in place to help set policy and approve big decisions, such as opening new offices.

But Gorrell was calling the shots. Some former Hogan partners say Gorrell doesn’t handle dissent well. One ex-partner describes the group of managing partners as Gorrell’s “acolytes.” Another calls them “his guys, his inner circle.” But even some of Gorrell’s critics concede that the people he installed in management roles were well qualified.

Most important among the senior managers has been Prentiss Feagles, managing partner of finance at Hogan & Hartson, now co-head of finance at Hogan Lovells.

Feagles joined Hogan & Hartson in 1980, the year after Gorrell arrived. The two have been friends ever since. Because their practices are complementary, they often work on the same deals. While Gorrell negotiates mergers and acquisitions for major companies, Feagles takes care of tax questions that arise in the complex transactions. Partners describe both men as brilliant.

“Prentiss has done a phenomenal job on the financial side and the business side,” says Hogan’s Ty Cobb. “He’s a huge ally of Warren’s. They’re great collaborators.”

Gorrell is a savvy businessman in his own right. Before he went to law school at the University of Virginia, he got an economics degree from Princeton. But Gorrell wanted someone to focus exclusively on the firm’s finances, and Feagles was his first choice.

Law firms generally rely on banks and credit lines to help cover costs through the year because the push to collect fees from clients isn’t made until year’s end. But Gorrell and Feagles were nervous about depending too heavily on loans. They made a key decision in 2002.

“The banks are your friends, but when things become difficult, they have their own interests to protect,” Feagles says. “You’re much better off preserving yourself by not depending on outside financing.”

So Gorrell and Feagles increased the amount of capital that partners were required to put into the business. Capital contributions were raised gradually over an eight-year period as the firm’s reliance on banks was reduced. Today Hogan’s partners say the firm is debt-free.

Next: Ruyak finds an ally in Mark Wegener

Down the street at Howrey, Ruyak found an important ally in his partner Mark Wegener, who some say had a better understanding of law-firm economics. And unlike Ruyak, Wegener had no trouble being the heavy.

“Mark just had a steel nerve,” says former Howrey executive-committee member John Taladay. “He was as no-nonsense as you’d ever want to meet. Mark was the person Bob turned to to execute on things.”

Wegener became managing partner of finance and was put in charge of collections, meaning he was the one who pushed lawyers to collect money from their clients. Attorneys are notoriously uncomfortable with this process and often need extra encouragement to get cash into the firm.

“People didn’t want to get a phone call from Mark Wegener,” Briggs says. “He was a terror when it came to collecting money.”

Wegener was a vice chair of the firm’s executive committee, which had six partners, including Ruyak, its chair. The body was in charge of policy- and strategy-setting and approving investments, while the heads of Howrey’s three practice areas were tasked with monitoring the business of their groups.

The executive committee was supposed to make decisions together, but former members say Ruyak often presented ideas that were “prepackaged” without soliciting debate or input from the full committee.

“The way things worked, it was like Bob would say, ‘This is what I’m doing. Does anyone disagree?’ ” Briggs says.

When Wegener sat on the committee, says a source close to management, this wasn’t as much of a problem, because if Wegener wasn’t sold on an idea, Ruyak listened to him.

Ruyak disagrees, calling the executive committee a team effort: “To think that any one person or two people were making decisions for the firm is ludicrous.”

Another highly respected member of the committee was Cecilia Gonzalez, who also acted as a sounding board for Ruyak. Both Wegener and Gonzalez were respected among their partners. They were also two of the firm’s biggest rainmakers. Wegener generated as much as $25 million in business a year; Gonzalez could bring in about $20 million.

“People didn’t want to get a phone call from Mark Wegener. He was a terror when it came to collecting money.”

Even early in Ruyak’s tenure as managing partner, when the firm was doing well, it got itself into some troubling situations.

In 2000, Howrey filed a class-action suit against tobacco companies on behalf of tobacco farmers. Howrey took the matter on a contingency basis, meaning the firm wouldn’t get paid until it won or settled the case. Contingency cases are gambles for law firms because they require an investment up front with no guarantee of making it back. In usual billing arrangements, clients pay by the hour, so revenue is more predictable.

The tobacco case, led by antitrust partner Alan Wiseman, turned into a huge investment, consuming in the range of $20 million worth of resources and lawyer time. Some partners began to get nervous.

“Partners were looking at it, going, ‘What if it just craps out? Or what if it actually goes to trial and then goes to appeal and just keeps getting dragged out?’ ” recalls Sean Boland, who later became co-head of the antitrust practice and a vice chair of the firm.

Relief came at the end of 2003, when the tobacco class action finally settled. Howrey got a payment of about $75 million. For the first time, Howrey’s profits per partner—what the average partner makes for the year—hit the $1-million mark.

“So for the larger audience of the firm, it was validation of strategy. Happy days are here again,” says Briggs. “But the takeaway [within the executive committee] was ‘Boy, we can never ever let this happen again. We can never get ourselves into an investment this large’—a little bit like a land war in Asia.”

Because of their big 2003 payday, Howrey’s lawyers seemed to lose some motivation in 2004.

“I recall the complacency,” Boland says. “People saying, ‘Jesus Christ, if we can top off our year every year with one contingency case, we’re golden.’ ”

But there was no contingency win to buoy the performance in 2004. The firm missed its revenue target by 6.5 percent, with profits per partner falling to $775,000.

Over the coming years, Howrey would invest even more heavily in risky contingency work, even as the economy worsened around it.

Strategic Expansion

Warren Gorrell was set on continuing the expansion of Hogan & Hartson that began under Bob Odle.

Even before he became firm chairman, Gorrell had garnered firsthand experience opening new offices. The firm had sent him to New York in 1998 to start its outpost there, and his work growing that office continued into the early part of his chairmanship.

Gorrell engineered acquisitions of two small Manhattan firms to bolster Hogan’s presence. When Gorrell acquired the prestigious firm Davis Weber & Edwards, it was viewed as a coup. “People went, ‘Wow,’ because they were one of the very hottest litigation boutiques in the city,” recalls New York legal recruiter Jon Lindsey.

The 2002 acquisition of Squadron Ellenoff Plesent & Sheinfeld, which along with Hogan had represented Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp., made the firm News Corp.’s primary legal counsel. The media giant continues to be Hogan Lovells’s biggest client.

Gorrell’s ultimate vision, though, extended beyond New York. During his tenure as chairman, Hogan & Hartson opened eight international offices on three continents.

“Looking at what’s happening in the world, we saw that globalization was real, and if we were going to be a part of it with our clients, we needed to grow internationally as well,” Gorrell says.

Deciding where to open was a delicate task. “It wouldn’t simply be because somebody thinks it would be neat to have an office in Paris,” says Robert Johnston, who was executive director of Hogan & Hartson and has the same position at Hogan Lovells. “There’s got to be a business reason that’s driven by practice and client needs.”

Johnston says that once a business reason was identified, he would work on rigorous models showing projections over the next two to three years of what it would cost to staff and operate the office and what the expected revenue would be. Only then would the executive committee decide whether to approve the plan.

Next: Hogan & Hartson’s international offices open

Three of the international offices—Geneva, Caracas, and Hong Kong—opened in 2005. Caracas was a direct response to client demand. Hogan already had a significant Latin American practice based out of Miami, with Venezuela’s state-run oil company, PDVSA, as a client. Geneva was fueled by a desire to develop an international arbitration practice in Europe. As for Hong Kong, Gorrell hoped that office would attract capital-markets work from the Chinese companies already serviced by its Beijing and Shanghai lawyers.

For any law firm, predicting the performance of new offices—especially international ones—is hard. Gorrell says his motto when choosing where to grow is “know thyself”—that is, examine your own strengths and weaknesses to determine whether a particular market makes sense. The motto also applied when deciding where to close offices.

In the mid-2000s, Hogan & Hartson closed two of its smaller international outposts, in Budapest and Prague, both of which opened in the ’90s under Odle.

“I think there was a lot of optimism in the immediate period after opening in Eastern Europe,” says Stephen Immelt, who was managing partner of international offices at Hogan & Hartson. “There was a lot of infrastructure and development work that happened there in the ’90s, but at least for us, those practices did not develop to a point where you could sustain them.”

Down the block at Howrey, the ambitious international expansion lacked discipline, say former Howrey partners. While Hogan & Hartson’s more diverse mix of practices, particularly its strength in corporate law, meant there were more natural opportunities for it to get work internationally, Howrey’s narrower focus on litigation limited its potential outside the United States.

At first, Ruyak played to Howrey’s strengths. In 2001, Howrey opened a large Brussels office that built on its reputation for antitrust work. Just as Washington is the center of antitrust regulation in the United States, Brussels is where the European Union’s antitrust battles are based. The firm’s former partners agree that the outpost was consistently profitable.

John Briggs went to Brussels to start the office for the firm. He says that intensive research was done there before opening but that performing that kind of due diligence wasn’t typical for Howrey. “We didn’t do things by studying very much,” he says.

That approach got Howrey into trouble elsewhere. Its London office was a constant problem. Though it officially opened in January 2001, Savarese had overseen the details of the opening while he was still managing partner. The firm signed a lease in London’s pricey financial district in a building shared with much wealthier tenants, including Goldman Sachs. Ex-partners say Howrey had no business renting such expensive space.

Howrey later moved to a more affordable building, but the office still failed to make money.

“It was ill conceived going in,” Sean Boland says. “We should have closed it years ago.”

Howrey also opened in Paris in 2005, when it acquired a small intellectual-property firm. That office didn’t make money, either.

“The problem with Paris is that it created enormous conflict issues for us,” says John Taladay. “[The Paris firm] had a very good client base in the pharmaceutical sector, but it ran headlong into a lot of the pharmaceutical clients Howrey had. And it cost us some big clients ultimately.”

Ruyak was “a visionary,” colleagues said, but did he understand the business?

Three years after Paris, in 2008, Howrey acquired a Madrid antitrust firm, causing more financial woes. Partners say the Madrid firm had gotten most of its work through referrals from large firms that were competitors of Howrey’s. Once the Madrid lawyers became a part of Howrey, the workflow stopped, because Howrey’s competitors didn’t want to send business to a rival.

Ruyak says it was important to grow Howrey in Europe because its patent-litigation and antitrust practices were becoming “increasingly international in scope, and our business plan called for a European presence in these areas to remain competitive.”

Ex-colleagues say Ruyak’s vision led to a loss of focus. “I think he was busy acquiring offices in Spain and other places rather than looking at the fundamentals of the firm,” said Henry Bunsow, then a Howrey vice chair, when he left the firm in January, a couple of months before it dissolved.

But blame doesn’t rest solely with Ruyak. His fellow partners—all owners of the firm and entitled to a say in its direction—and the executive committee didn’t stop him.

Even as Howrey neared its end, with profits bottoming out and partners fleeing, it didn’t close any of the underperforming offices. In fact, in 2010, it opened another office, in Düsseldorf, Germany.

Taladay, who was on the executive committee at the time, says he was “shouted down” for opposing the office: “It was opening just another place where we were going to drain some money.”

Rough Waters

The global economy had been growing for years amid rising stock markets and housing bubbles. In 2007, easy credit began grinding to a halt, marking a turning point for the entire legal industry, which had enjoyed a decade in which firm sizes, salaries, and billable hourly rates all seemed to go in only one direction: up.

In the months after the credit crisis hit in 2007, work dried up and law firms began to feel pressure from clients who were no longer willing or able to pay their legal bills. Lawyers were laid off by the hundreds. A few firms collapsed.

Not Howrey—at least not at first.

In fact, Howrey had its best financial performance ever in 2008, thanks in part to another contingency win. Howrey lawyers had worked on the case for client Fifth Third Bank for 13 years and finally won in March 2008. The award pumped $23 million into Howrey, helping to increase the firm’s revenue by more than 20 percent—but the contingency payment masked the realities of the faltering economy.

“When we got the Fifth Third money, senior management did not say, ‘What is the underlying health of the firm?’ ” says former partner Matt Wolf. “So even though 2008 was a good year in terms of numbers, our productivity was dropping dramatically.”

Howrey increased its employee head count in December 2008, adding 40 litigators from Thelen, a law firm that had dissolved under the strain of the economic downturn. Lawyers in that group say they weren’t given a complete picture of Howrey’s financial situation.

Andrew Ness, who had been managing partner of Thelen’s DC office, says Ruyak led the effort to recruit his team.

“He was clearly the salesman-in-chief, and he did a darn good job at it,” says Ness. “I remember being told that despite the fact that the economy was essentially collapsing around everyone’s heads, 2008 was going to come in well over budget with record revenues and profits.”

But Ness says Ruyak left out an important detail—that the Fifth Third win was a significant part of the firm’s 2008 performance. Because contingency payments are based partially on luck, law firms typically don’t count them as real financial growth. Ness says he didn’t find out that the Fifth Third payment had inflated revenue until after he had already joined Howrey.

On top of the contingency situation, the firm lost two of its biggest rainmakers in the space of a year.

Wegener became ill with cancer and died at age 59 in June 2008.

Next: Hogan & Hartson make drastic changes

J. Warren Gorrell Jr. had grown Hogan to 27 offices, but he needed a game-changer. Photograph courtesy of Hogan Lovells

“When Mark was passing, Bob Ruyak spent a ton of time at his bedside,” says Wolf. “It was emotionally exhausting. Not only did we lose Mark; we didn’t have Bob for a lot of that stretch because he was doing what he felt as a human being he should be doing. Many of the senior managers, the practice-group leaders, failed to step up at that time.”

When Wegener got sick, Cecilia Gonzalez—whom some viewed as the logical successor to Ruyak—replaced Wegener as the firm’s vice chair. But in May 2009, not even a year after Wegener’s death, Gonzalez died of breast cancer at age 53.

Beyond the loss of the combined $40 million–plus worth of business, the loss of two of the firm’s key leaders meant that the dynamic on the executive committee was never the same again. Some partners today speculate that Howrey wouldn’t have dissolved if Wegener and Gonzalez had lived.

As the economy worsened, Gorrell says he felt even more urgency to turn Hogan & Hartson into a preeminent global law firm. Multinational companies were consolidating their legal work into fewer firms to save money, and Gorrell wanted to position Hogan to be one of the firms that big corporations would think of first to house all of their legal needs.

By 2008, he had expanded Hogan & Hartson from 15 offices to 27. But adding one office at a time wasn’t working quickly enough. Gorrell had promised his partners early in his tenure that he wouldn’t enter a transformational merger, but the world had changed since those early days of the 21st century.

Hogan needed a game-changer.

Gorrell had known lawyers at the London-based firm Lovells for years. Of the major UK firms, Lovells had the biggest geographic footprint. Gorrell and Lovells partner Patrick Sherrington had become friends while serving as representatives to a law-firm association called the Pacific Rim Advisory Council.

Hogan & Hartson and Lovells were about the same size and made roughly the same amount of money. Though Lovells had a strong international presence, it had very few US-based lawyers. Hogan was just the opposite, with only 20 percent of its attorneys outside the United States. At first glance, the firms seemed as if they could be great geographic complements to each other. Still, Gorrell hadn’t seriously considered the possibility of merging with his friend’s firm before a fateful meeting in Los Angeles.

Gorrell and Sherrington found themselves in LA at the same time in July 2008. They arranged to have drinks at the bar of the Hyatt Regency Century Plaza hotel, across the street from Hogan & Hartson’s LA offices. As the men talked about the economic challenges confronting their industry and the importance of law firms’ helping one another out during such a hard time, Sherrington brought up the prospect of merging. Between sips of Cabernet, Gorrell agreed that it was worth considering.

The idea was exciting, but Hogan still had to deal with the difficulties of the economy. By the fall of 2008, Prentiss Feagles says, things were “becoming darker.” The firm began to think about ways to cut costs.

It initially offered an early-retirement package to staff, but when only 27 people took it, the firm turned to more drastic measures. It reduced some salaries and laid off 93 staff members by the spring of 2009.

Howrey had held strong. By 2009, it was one of the few large law firms in the country that hadn’t had mass layoffs. Despite the turmoil in the legal industry, Ruyak was still relatively optimistic about how the year would turn out. He predicted early in 2009 that the firm would come in 10 percent under its projected financial performance—a significant shortfall but one that could be survived.

“It’s not as though it was going to be a killer year,” says Taladay. “The economy just didn’t support that.” The mentality among many partners was to squeak by at 90 percent of budgeted profits and hope for a better 2010.

They wouldn’t be so lucky.

Partners say they historically didn’t have access to clear financial information throughout the year, and 2009 was no different. Ruyak disagrees. He says he and other members of management were transparent about Howrey’s financials and were responsive to partner inquiries.

Ruyak’s former colleagues say one problem was that he focused on “demand.” This was the number of hours Howrey’s lawyers were billing to clients. It conveyed how busy the firm was, but not how profitable. At the end of 2009, it was evident that lawyers had been discounting their rates as clients hit by the economy became less willing to pay full price. No one had been keeping close enough watch on the discounts.

Another problem with measuring demand at Howrey, the firm’s former lawyers say, was that hours spent on contingency cases were sometimes counted the same as time spent on matters that got billed by the hour. Because contingency work doesn’t bring in cash until a case is settled or won, those hours weren’t generating immediate revenue—and might never generate revenue. Yet the firm was invested heavily in the work.

In 2006, a team of lawyers led by partner Robert Abrams had begun working on a large-scale class action representing dairy farmers alleging a monopoly among milk producers. By the time Howrey collapsed in March 2011, the firm’s investment in the milk case was about $40 million, and it hadn’t produced any revenue.

Abrams was also working on another contingency case on behalf of consumers suing Netflix and Walmart over their online DVD sales and rental arrangement. The investment in this case was about $5 million. It also didn’t make any money before the firm dissolved.

“I was at Howrey for 38 years,” says Abrams. “Whenever I was asked to do a case, I did it. I never turned down a request for my involvement.” He disagrees with partners who say contingency investments contributed to Howrey’s collapse. Abrams says the cases were monitored by the firm’s contingency committee, which was set up to determine whether to take a contingency case and then to keep tabs on the investment in it. He says the suggestion that the work was a factor in the firm’s dissolution is “a red herring.”

Next: An exodus at Howrey

Ruyak says he thinks the contingency committee made “sound decisions.” But when demand for non-contingency work dropped, the contingency work became too large of a percentage of Howrey’s workload. Howrey historically had tried to limit contingency matters to 4 or 5 percent of its total workload. Ruyak says that proportion grew to 8 percent throughout 2009 and 2010. Other partners put it at 11 percent.

The hours devoted to contingency matters could skew the picture of Howrey’s health. Taladay remembers looking at an assessment from 2009 of the hours worked by one group of associates. On paper, they appeared to be billing more than 1,700 hours each on average. But when pro bono and contingency work was stripped away, the number of cash-generating hours dropped below 1,300 hours.

When the 2009 books closed, the firm had come up 30 percent short of projected profit. It had been a disastrous year, yet partners say there had been no warning.

“In December of 2009, I remember Bob Ruyak sent out a memo that said, ‘We can still meet our goals,’ ” Boland says. “He just was so optimistic that instead of sending the message ‘Hey, we’ve got to try to collect every damn penny,’ the message the way most people read it was ‘Hey, we’re going to be okay.’ People can take bad news, but you need to prepare them for it. People were just shocked.”

The most consistent criticism of Ruyak’s leadership is that he couldn’t make tough decisions or deliver bad news. “Bob sometimes had a hard time telling people no,” Taladay says.

As Howrey began to founder, some partners perceived Ruyak’s optimism as deceitful. When firm profits dropped dramatically, partners felt blindsided. One of them, Jeffrey Gans, says, “We got a picture of a firm that was more financially strong and stable than actually existed.”

Yet during Ruyak’s tenure as firm leader, he became known for launching new initiatives, such as an innovative training program for first-year lawyers. And for the most part, his colleagues liked him.

“Even at the point in time where people started questioning his every decision,” Taladay says, “they still personally liked Bob in a way that I don’t think anyone else could have achieved.”

“Bob sometimes had a hard time telling people no.”

The full extent of the 2009 performance wasn’t explained until the annual partners’ retreat in March 2010 at the Ritz-Carlton in Key Biscayne, Florida. The retreat was historically a lighthearted affair—a chance to bond with colleagues in a tropical place. Key Biscayne was a popular destination for the Howrey partners, though the annual meeting had also been held in Puerto Rico, Grand Cayman, and other locales. But this year, as the partners filtered into the Ritz’s ballroom to hear Ruyak’s presentation, the mood was tense. Whatever their managing partner said here would be critical to the firm’s future.

Ruyak’s message was that no one—not even he—could have anticipated the 30-percent shortfall. Ruyak had always been known as a superb salesman, and that skill was on full display as he reassured the crowd that the firm would do everything it could to get back on track for 2010. Many partners left the meeting feeling better, though several who attended say a group of Howrey’s European partners couldn’t be consoled. They felt they had been misled by Ruyak and had started to discuss their exit strategy.

Ruyak also failed to mention a critical detail at the Florida meeting. Partners who joined Howrey in late 2008 and 2009 had been required to make only a limited investment in supporting the firm’s contingency cases because those cases had been initiated before they arrived at the firm. As a result, when the 2009 profits were divided among Howrey’s partners, the new lawyers who weren’t heavily invested in the contingency work got bigger checks than did the older partners who had more money tied up in the contingency work. During his financial presentation, Ruyak said that partners would take home an average of about 70 percent of their projected profit shares in 2009. Ruyak didn’t mention that this number was buoyed by the new partners, who made closer to 80 percent. After the retreat, some of the older partners looked at their reconciliation statements and saw that they had made closer to 60 percent. Some assumed that the 70-percent figure had been a lie. If Ruyak’s assurances during the meeting had eased their concerns, this realization shook them up again.

An exodus of Howrey partners began—though not all of the departures were unwelcome. The firm’s management finally had decided to thin the ranks, pushing under-performing partners out the door. Though the move was clearly necessary for the long-term health of the firm, it cost about $22 million in severance and other expenses.

In September, a group of seven partners—mostly in their forties—determined that more drastic changes were needed to save Howrey. Taladay, a young star in the antitrust practice, organized and led the group. Colleagues say that at this point Taladay was one of the only members of Howrey’s executive committee willing to speak up and ask tough questions. Another of the seven was Matt Wolf, a partner in the intellectual-property group who was widely thought to have his sights set on becoming managing partner of Howrey one day.

“I think we all realized that when we looked at the next 20 years, the people we wanted to practice with were sitting down the hallway,” Taladay says. “We really wanted to try to make this work.”

These fortysomething leaders were regarded as part of the heart of the firm and certainly necessary to its future. They came to be known as Young Turks, though their goals stopped short of revolution.

The group set out to effect changes. It wanted Howrey to be more democratic when it came to making big decisions. The seven partners wanted the full partnership to vote on future office openings and additions of significant groups of lawyers. They also thought Ruyak was no longer a credible source for financial information. They told him they wanted Sean Boland, at that point a vice chair of the firm, to take over responsibility for communicating financial information. But they stopped short of demanding that Ruyak be removed from power.

“The firm could not have survived Bob Ruyak being removed as managing partner,” Taladay says. “To the external world, to the bank, he was managing partner of the firm. To pull that straw out would have been devastating.”

Not everyone agreed. When members of the group began going from partner to partner to spread the word about the plan and met with Andrew Ness—who already had survived the collapse of his previous firm, Thelen, in 2008—Ness told them he didn’t think the changes were radical enough.

“You’re not going far enough, fast enough,” Ness says he told the Young Turks. “What this firm needs is a major change at the top that’s branded as such—and announced as such—so that people have the confidence to stay the course and see what new management can do.”

Next: “It was all downhill from there.”

In November, Howrey’s top partners hunkered down for three days of meetings at Virginia’s Lansdowne Resort. It was clear that the partners were fracturing into different camps. On the second day, conversations got heated. The group spent the morning listening to Boland, who was head of the committee in charge of pushing lawyers to collect money from clients. Boland was trying to motivate his colleagues to collect as many outstanding fees as they could. He told them that eking out an extra few million dollars could make a significant difference.

After Boland’s presentation, Ruyak took the stage. He stressed that the firm had significantly cut costs and was much better positioned going into 2011. But some of the lawyers weren’t buying it.

Later in the afternoon, the group took a break and a few senior partners took Boland aside in a conference room. Boland had been in frequent communication with Howrey’s primary lender, Citibank. Fears that the bank would pull its financing of the beleaguered firm had been building.

Howrey was on the verge of breaking a covenant with Citibank. Covenants specify conditions that recipients of loans must comply with. When they aren’t met, the bank is alerted to potential trouble. In this case, says Boland, it looked as though Howrey was going to break an agreement to pay off its credit line with Citibank by the end of the month. Boland says he told the partners that during his conversations with Citi, there was no indication the bank was planning to shut Howrey down. And ultimately, Boland says, Citi waived the covenant. Still, the partners couldn’t be placated. When the meeting reconvened, Ruyak faced tough questioning and acknowledged that Howrey might not be able to pay off the credit line in time.

The seven Young Turks were also on the agenda at Lansdowne. They were more optimistic about Howrey’s prospects than many of the veteran partners. But when they got up to explain their vision, it didn’t go well. Wolf says some senior partners felt excluded.

“When the first comment was one of the senior people saying, ‘I’m pissed off that I wasn’t included in this plan,’ that set the tone of the discussion,” Wolf says. “It was all downhill from there.”

There also was no sense of urgency, says Wolf. He says Ruyak said the firm should institute the changes over the next 12 to 18 months. “We said, ‘No—no, this needs to be done now,’ ” Wolf recalls.

Unlike in 2009, when Howrey’s lawyers were shocked that they came in 30 percent below the expected financial performance, at the end of 2010 many of them hoped the firm would underperform by only that amount.

That was wishful thinking. Howrey came in 45 percent short of expected profit in 2010.

Ruyak says operating costs were reduced by almost $40 million between 2009 and 2010. He and other Howrey lawyers say the positive effects of those reductions would have been realized later in 2011 if partners had been willing to hang on a bit longer. But too many had lost faith in the firm.

Howrey’s demise became a self-fulfilling prophecy as partners fled—taking client matters with them—further weakening the firm.

Howrey needed a life raft in the form of a merger.

Down the block at Hogan & Hartson, the idea of a merger was very much on the table, but under much happier conditions. Discussions with Lovells had proceeded throughout the summer of 2008.

After Gorrell and Sherrington’s initial meeting in July, both men brought more members of their firms’ leadership into the conversation. Later that month, Gorrell and Feagles flew to London to meet with Sherrington and Lovells’ managing partner, David Harris. It was imperative that no one outside the small group of firm leaders find out about the discussions. As an extra precaution, Gorrell signed in under a fake name with the security desk at Lovells’ London headquarters. While visiting the office, Gorrell would go by “Mr. Spencer.”

“The initial focus was purely on the business and the clients,” says Gorrell of the talks. “If it didn’t make sense from the client perspective, even though it might otherwise look good on paper, it wouldn’t make sense to waste any time considering it.”

There were, not surprisingly, a number of client conflicts. For two large firms, each with thousands of clients, that was to be expected. But none of the conflicts was a deal-breaker, and the talks intensified in 2009.

Practice heads from each firm began meeting their counterparts. Management drilled down on how to reconcile differences between the firms’ compensation and governance systems.

In November 2009, the full partnerships at each firm met to discuss details of the merger. In mid-December, they voted on it.

After months of build-up, the moment when Gorrell voted to approve the union—a decision that would define his legacy at the firm—passed without excitement. Alone at his computer in his large corner office overlooking downtown Washington, Gorrell entered his vote electronically. In that instant, he felt a number of things—relief and optimism but also anxiety. People were congratulating him, but he couldn’t help thinking the hard work was still ahead.

Gorrell and Harris, Lovells’ managing partner, became co-CEOs of the combined firm when the merger became official on May 1, 2010.

Next: The next chapter

Howrey’s merger plans never got off the ground.

Boland says he met in October 2010 with Ruyak to discuss a merger in general, and then in November—the same month as the Lansdowne meeting—to discuss merging with the firm Winston & Strawn. Consultant Peter Zeughauser, who had a working relationship with both firms, set up a meeting before Thanksgiving among Ruyak; Boland; Winston & Strawn’s managing partner, Thomas Fitzgerald; and its chairman, Dan Webb. The men convened over dinner at the City Club—located just above Hogan & Hartson’s offices in the Columbia Square building.

Rumors about the possible merger started circulating among Howrey’s lawyers. In late January 2011, management officially told the partnership about the effort to make a combination with Winston work. Ness says there was no mention at this meeting of the possibility of Howrey’s continuing as an independent entity.

Yet the chance of a successful merger quickly began to slip away. There were major client conflicts. Howrey’s huge milk-antitrust class action conflicted with Winston & Strawn clients. Winston had a lot of generic pharmaceutical clients, while Howrey represented big, brand-name pharmaceutical companies. And many of Howrey’s top partners continued to leave, making the firm a less desirable merger prospect with every passing week.

Ultimately, the possibility of a full merger fell apart, though Winston ended up hiring about 40 Howrey partners. Boland, who led the merger discussions, didn’t go to Winston. He left Howrey the day it went under, taking 45 lawyers—including Taladay—with him to the firm Baker Botts.

Howrey had run out of options.

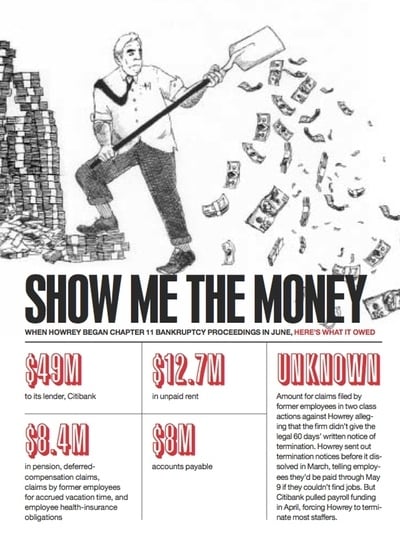

On March 9, 2011, its partners voted to dissolve the firm. The dissolution was effective on March 15. Howrey was pushed into an involuntary Chapter 7 bankruptcy by creditors in April but was able to convert the proceedings to a voluntary Chapter 11 bankruptcy in June. In its initial Chapter 11 filing, Howrey reported that it owed $49 million to Citibank.

The Next Chapter

As Howrey did after it collapsed, Hogan & Hartson held an auction before the merger to sell off everything branded with the firm’s name. Gorrell purchased the Hogan & Hartson sign that had once adorned the outside of the Columbia Square building. It now resides on a shelf in his office.

Hogan Lovells, larger and more powerful than ever, still occupies the same building. A small bronze nameplate announces HOGAN LOVELLS to passersby.

Gorrell’s anxiety about the merger’s challenges wasn’t unwarranted. Matching up the Hogan and Lovells sides hasn’t been easy. More than 100 lawyers left the two firms in the months before they combined, and some offices closed, including Hogan & Hartson’s Geneva office and Lovells’ Chicago office. The departing lawyers often cited client conflicts resulting from the merger as their reason for leaving.

But more than a year into running the combined firm, Gorrell says the challenges of completing a mega-merger have been well worth it.

Today, roughly 45 percent of the firm’s business is in the United States, 45 percent is in Europe, and the remaining 10 percent is in Asia and the Middle East.

The combined firm, which grossed $1.66 billion in its first year, now handles an even broader portfolio of work across corporate, litigation, regulatory, intellectual-property, and financial practices. The 800 partners who gathered at National Harbor were making an average of $1.14 million.

“If you could have told us going into the merger that we could deliver that kind of performance in the first year, despite all the market challenges and the distractions of the merger, we would have closed the books on the first day and moved forward,” Gorrell says.

Down the block, Howrey’s former office is vacant. The collapsing firm moved out of the Warner Building shortly after the bankruptcy auction in August, though it’s still embroiled in a lawsuit attempting to get the landlord’s demand for $2.8 million in rent thrown out.

In a testament to the firm’s onetime greatness, most of its partners landed quickly at other firms.

Howrey’s milk case and the case against Walmart and Netflix are ongoing. Robert Abrams, the partner who led both matters, took them to his new firm, Baker Hostetler. While many blame those contingency investments for contributing to the firm’s demise, they’re now one of the Howrey estate’s last hopes. The tens of millions in payouts that could come from the cases’ resolutions could ease the financial strain on Howrey.

Bob Ruyak remained committed to Howrey until the end. He stayed on to wind down operations until he joined Winston & Strawn in September. He was not, however, doing the wind-down work for free. A bankruptcy filing in August showed that the Howrey estate paid him more than $113,000 for the month of July.

Ruyak is once again a full-time practicing trial lawyer. He doesn’t have any management responsibilities at his new firm.

Of his time running Howrey, he says he did the best he could: “I have no regrets.”

This article appears in the December 2011 issue of The Washingtonian.