One architecture critic called Dulles a “fleeting vision of a white Viking boat sailing the rolling meadow.” Photograph by Ezra Stoller/Esto

The crews had scrambled through the night and into the early morning, but at 4 AM on November 17, 1962, the orders came to stop and go home. Dulles International Airport wasn’t finished—a few final touches had yet to be applied. But in just four hours, the terminal would be opening, with two Presidents, a chief justice of the Supreme Court, and thousands of spectators expected at a dedication ceremony.

During those early days of jet travel, New York City was the primary point of entry to the United States for diplomats and tourists. Dulles was going to change that, promising to transform Washington into an international gateway. That the airport was the first in the world built expressly for jet aircraft distinguished it from National Airport, whose runways were too short for jets of that era to land.

So it was with great anticipation that the spectators began to gather. The crowd grew to 60,000—an anticipated 40,000 more had been kept away by gloomy skies and intermittent rain. Those who endured the weather were rewarded with a glimpse of a building unlike any other in or around the nation’s capital—a strange and wondrous structure, a giant bird of concrete and glass alighted upon the Virginia countryside.

Inside, Secret Service officials did security sweeps, readying the terminal for President John F. Kennedy and his predecessor, Dwight D. Eisenhower. When Eisenhower arrived, he made his way to the south concourse, where a bronze bust had been installed, sculpted by Boris Lovet-Lorski. It depicted the man for whom the airport was named, John Foster Dulles, Eisenhower’s Secretary of State, and it was before this sculpture that the former President shared a quiet moment with members of Dulles’s family—his widow, Janet, and his brother, Allen, former director of the CIA.

Outside, the spectators huddled in rain gear, for the moment subdued. But then President Kennedy’s helicopter was spotted in the sky, having taken off from the White House ten minutes before. Its touchdown sent a charge through the crowd. A photograph taken that morning shows Kennedy emerging from one of the airport’s “mobile lounges” to greet the thousands in attendance—smiling, confident, eschewing both overcoat and hat despite the 54-degree chill.

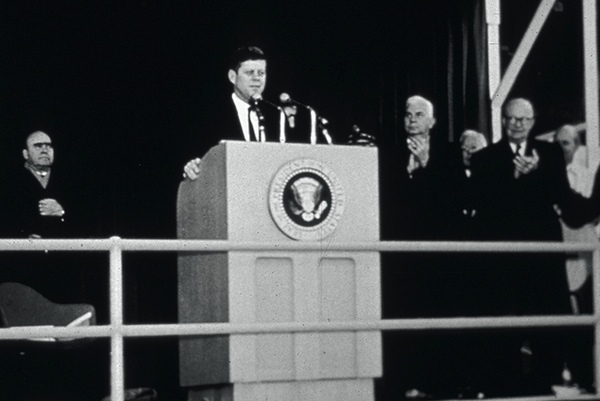

With the US Army Band playing “Hail to the Chief,” Kennedy made his way to the speaker’s stand, where he took his place alongside Eisenhower; Janet and Allen Dulles; Chief Justice Earl Warren; Aline Saarinen, widow of the airport’s architect, Eero Saarinen; and Najeeb E. Halaby, head of what was then called the Federal Aviation Agency.

The crowd grew silent as Eisenhower stepped to the podium. He remembered the time more than five years earlier when General Elwood Richard Quesada—Eisenhower’s adviser on aviation and later the first administrator of the FAA—convinced him that the capital needed a jet airport. He recalled asking Congress to appropriate the funds in 1957 and how the selection of a site had been “a knotty problem.” Most of all, he remembered his “very close friend John Foster Dulles,” who as Secretary of State traveled to many distant ports and whose name would forever be remembered by those who passed through this one.

Next: A time of change for Washington

It was a study in contrasts: the septuagenarian Eisenhower seizing the moment to summon the past and his successor, John F. Kennedy, almost 30 years his junior, taking the podium next to imagine the possibilities of the future. Dulles International Airport, Kennedy said, represented “the aspirations of the United States in the 1950s and the 1960s.” Image-conscious in terms of both self and country, Kennedy knew that for many foreign visitors, the first impression of the United States would now be formed by Saarinen’s modernist airport.

Here was a President projecting the image of the nation’s capital on the map of a shrinking world, a world in which the remotest outposts were becoming less foreign. It was a time of change for Washington as well—with the construction of the city’s first freeway, urban renewal in Southwest DC, and a building boom north of the White House that saw office buildings arise in brash clusters of glass. An article in the Washington Post from 1961 captured the optimism of the moment: “Everywhere one looks, steel framework, piles of earth, piers of concrete, walls of limestone and glass dot the townscape as the Nation’s Capital—not without reluctance—sheds its historic small-city atmosphere for that of a burgeoning metropolis.”

After Kennedy concluded his remarks, a series of jets took off and landed, and the Air Force Thunderbirds performed their aerial acrobatics. Visitors then boarded and toured planes parked on the runways and were free to explore Saarinen’s glass-paneled terminal.

“At long last,” wrote Washington Post architecture critic Wolf Von Eckardt, “Washington has a truly outstanding modern building by a truly outstanding modern architect.” In the estimation of some critics, the opening of Dulles was the biggest thing to happen to Washington architecture since Charles Bulfinch reconstructed the US Capitol after the British set it ablaze in the early 1800s.

And yet it wasn’t clear whether anybody would actually abandon National or Baltimore’s Friendship Airport—which could also accommodate jets—in favor of the new facility. As Post columnist Drew Pearson put it, “Will [Dulles] remain empty, its ticket counters barren of business, its skycaps idle, its escalators with no more than a trickle of suitcases? . . . Some people are wondering whether Dulles Airport, with all its beauty and all its perfect aeronautical techniques, may become another white elephant.”

“At long last, Washington has a truly outstanding modern building by a truly outstanding modern architect.”

The march to build a jet terminal near the nation’s capital may not have matched the ardor of the space race, but once Chantilly was selected as the airport’s site early in 1958, activity proceeded with considerable speed.

In May of that year, the New York engineering firm Ammann & Whitney was chosen for planning and construction. Eero Saarinen was commissioned as architect. A parcel of nearly 10,000 acres of farmland in Loudoun and Fairfax counties was acquired. And in September, bulldozers moved in to clear the site.

That Saarinen, an established modernist architect, was asked to design the airport would have seemed impossible two decades earlier. In the late 1930s, Saarinen was a young architect working in Michigan with his father, Eliel Saarinen, who had emigrated from Finland in 1923, when Eero was 13. Father and son, along with Eero’s brother-in-law, Robert Swanson, entered a 1939 competition to design the Smithsonian Gallery of Art, a proposed repository of modern painting and sculpture—a kind of MoMA on the Mall—to be built across the street from the National Gallery of Art, then under construction.

From a field of more than 400 entries, the Saarinen design—which called for a marble exhibition hall and two five-story wings along a curved reflecting pool—was the unanimous winner of the $7,500 prize. The design was lean, crisp, and modern—too modern, it turned out, for Congress. Detractors were appalled that such a building might exist in proximity to the neoclassical National Gallery. A clash ensued, and with Congress refusing to fund the Saarinen design, the Smithsonian Gallery of Art was never built.

The experience, disheartening as it must have been, didn’t prevent Eero Saarinen from relocating to Washington, which he did in the early 1940s, moving his family into a small house in Georgetown. Saarinen volunteered for the military and worked at the Office of Strategic Services (the predecessor of the CIA), where he served as chief of the presentation division.

Next: Saarinen’s departure from Washington architecture

John F. Kennedy hoped the airport would impress foreign visitors. Photograph courtesy of Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority

After the war, Saarinen continued to develop his own architectural style, seeking to distance himself from the glass-box modernism favored by the likes of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Saarinen embraced American postwar corporate culture, imbuing the glass-fronted office parks he’d helped popularize with a muscular brand of modernism. But his style also allowed for expressiveness, an indulgence in elegant curvature, a sense of motion and freedom, as best expressed in the Gateway Arch in St. Louis and the two great airport commissions he received while at the height of his powers: the TWA Terminal at New York’s Idlewild Airport (now JFK) and, three years before his death, the jet airport for the nation’s capital.

Saarinen’s challenge at Chantilly was to create a structure that was both a part of and a departure from Washington’s architectural tradition. “Federal architecture is static,” he wrote, “but a jet-age airport should be essentially non-static, expressing the movement and the excitement of travel. We thought that if we could bring these two things together into a unified design we would have a very interesting building.”

Saarinen’s building was stately and distinguished—its colonnade wouldn’t have been out of place among the capital’s neoclassical buildings. But it was what Saarinen did with those columns, setting them 40 feet apart and angling them in a dramatic outward slope, that gave the structure a feeling of movement. In seeming to capture that moment between stasis and takeoff, Saarinen designed a structure that was the embodiment of the jet age.

The airport’s columns supported light cables that supported the roof—an inverted arc of precast concrete that Saarinen likened to “a huge, continuous hammock suspended between concrete trees.” The metaphor, evoking the outdoors, wasn’t unintentional—like so many modernist buildings, this one was meant to bring the outside in.

Installing all that glass proved no easy task. Workers had to hoist 600-pound sections of glass into the air to place them on the terminal’s angled concrete frame. As project foreman Fred Allred said in the summer of 1962, “Frankly the men were scared at first. You see, each of those [panes] is a parallelogram, none of ’em is exactly square, and when you get up there and the wind starts blowing . . . . ”

The Post’s Wolf Von Eckardt called the finished product “a grand portal,” even if it seemed “almost dainty when you first see it, two miles away, from the approaching road: fleeting vision of a white Viking boat sailing the rolling meadow.”

Saarinen died on September 1, 1961, before the building was completed. Shortly before, he toured the work site with Kent Cooper, an architect and the airport’s project manager. As the men walked through the unfinished terminal, Saarinen kept staring at the roof. At one point he paused, unable to take his eyes off the great inverted arc above. “Boy!” he said. “This time we’ve really got something!”

Despite Saarinen’s enthusiasm, the airport was beset with problems from the start. For one thing, there was the matter of its name. John Foster Dulles had died of cancer in May 1959, and President Eisenhower used Executive Order 10828 to name the Chantilly International Airport after his friend. The decision angered locals for whom the name Chantilly had become a source of pride as well as those who questioned the politics behind naming an airport after a government official, dead or alive—unprecedented in those days.

Other controversies arose. An article in the Post in February 1960 identified “Dulles International’s No. 1 problem: How to get rid of the airport’s sewage without putting it in somebody’s drinking water.”

At the heart of the matter was a supplemental appropriations bill that allocated $750,000 to deal with airport waste instead of the $3.2 million that Eisenhower had requested. The bill called for the construction of a local treatment plant that would funnel effluent into Broad Run, a stream that flowed into the upper Potomac River. Many in Virginia were outraged, including flamboyant Virginia congressman Joel T. Broyhill, who said that polluting the Potomac in this way would be nothing short of “an international disgrace.”

Congress reached a compromise that kept airport sewage out of the Potomac, but the issue touched on an underlying tension. Dulles was a federal project, paid for by taxpayers, administered by a federal agency. Yet if the government failed to appropriate adequate funds, on whose shoulders would responsibility fall?

Next: The year 1959 marks a turning point

That Dulles and the federal government were so closely linked led to charges of impropriety, particularly in Maryland, where residents feared for the future of Friendship Airport near Baltimore. Since the moment it opened in 1950, Friendship—now Baltimore/Washington International Thurgood Marshall Airport—had been a burden on the coffers of Baltimore. The year 1959, however, seemed to mark a turning point. It was then that jet service came to the airport, and though Friendship still lost $174,000 that year, passenger totals increased, leading to a feeling of cautious optimism. Many of those travelers came from Washington.

With Dulles now challenging Friendship’s monopoly on the region’s jet service, Baltimore’s aviation authorities launched a $1.5-million campaign to expand and improve facilities. Friendship may not have been making any money, but the airlines were. Why would they leave a sure bet at Friendship, argued Baltimore’s director of aviation, John Q. Colonna, for the unknown territory of an airport that could potentially sit idle for years?

For Colonna and other Marylanders, any competition with the federal government was never going to be a fair fight. In February 1962, Charles P. Crane, chair of Baltimore’s airport board, threatened to take the government to court. Federal officials, he said, had a financial stake in luring airlines to their new airport. And after 13 airlines—including TWA, Pan Am, and Northeast—entered into agreements with Dulles that year, Maryland senator J. Glenn Beall took to the floor of the US Senate in August, calling Dulles “a federally conceived, federally planned, federally financed and federally constructed boondoggle.” The FAA administrator, Beall said, shouldn’t “wear the two hats of airport promoter and impartial aviation regulator at the same time.”

It wasn’t until 1987, after President Ronald Reagan signed a bill transferring administration of Dulles to the Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority, that the airport was removed from the immediate purview of the federal government.

OSaarinen toured the construction site shortly before he died. “Boy!” he said. “This time we’ve really got something!”

During his impassioned Senate speech, Beall also took aim at Dulles’s spiraling budget. The airport’s initial cost of $50 million to $60 million rose by the end to $175 million. As FAA administrator Najeeb Halaby admitted to Congress, mistakes and poor planning had led to both rising costs and construction delays. To Beall’s charge that the budget had been mismanaged, the government could offer no response.

There was another area in which mismanagement had led to problems: the airport’s mobile lounges. Much scorned through the years, these vehicles were an integral part of the airport’s design, considered revolutionary in the way they minimized a passenger’s walking time from parking lot to aircraft. You simply entered the terminal, checked in, and awaited a mobile lounge, which took you directly to your airplane—total walking distance: 200 feet.

Developed by the Chrysler Corporation and the Budd Company of Philadelphia, the lounges, which could accommodate about 100 passengers, eliminated “the time-consuming upstairs-downstairs routine of moving passengers from the departure level down to a tarmac-level bus and then back up to board the plane,” writes Antonio Román in Eero Saarinen: An Architecture of Multiplicity. The lounges were meant to be stylish places of repose, where you could read a magazine, smoke a cigarette, and chat up an air hostess while sheltered from the rain or snow.

The FAA was never really sold on the concept, and justifying the expense to Congress turned out to be a challenge—especially once the derisive reviews started coming in. Typical was an article in the Architectural Forum that called the mobile lounge a “lumbering beast, at best.” In February 1962, a House Appropriations subcommittee held hearings to review the FAA’s $811-million budget proposal for the following fiscal year, and the lounges came under fire.

“The field is great,” said Massachusetts Democratic congressman Edward P. Boland to Najeeb Halaby, who had been called to testify, “the building is magnificent, but why in the world did we ever get into this monstrosity of a mobile lounge?” The lounges, Halaby said, had been agreed upon before he became FAA administrator in March 1961. He conceded that the vehicle was a “beast,” but he also explained that the terminal had been designed with the lounges in mind and that retaining them would be cheaper than reconfiguring the airport.

So how much, Boland asked, did these lumbering beasts cost?

Next: The most expensive automotive vehicle ever

“Two hundred thirty-two thousand dollars apiece,” Halaby said. (The prototype had cost $1.8 million, including research and development.) “It is the largest, most expensive automotive vehicle ever produced.”

“And one of the ugliest,” Boland said.

“It is not handsome,” Halaby conceded.

When subcommittee chairman Albert Thomas, a Democrat from Texas, then learned that the FAA had committed to buying 20 of the lounges, he became incredulous. In Europe, he said, “they have a good old-fashioned bus to run passengers out to the planes. Nobody ever complains.”

When Halaby told him that the mobile lounges would be a great relief for weary passengers, Thomas said: “We ought to make them walk a bit. The next thing we will be providing personnel to carry people on to these planes.”

Fifty years ago, on December 7, 1961, the first jet—a Convair 880 owned by the FAA—touched down at Dulles at the end of a test flight. It was a landmark moment that didn’t quite alleviate airport officials’ concern. In early 1962, the FAA predicted massive deficits at Dulles, with Halaby conceding in May that the airport wouldn’t make money until probably the early 1970s. As reporter John J. Lindsay wrote in the Post, “It looked as though Washington were going to have the safest, most modern, jet airport in the world without any passengers.”

Sure enough, Dulles endured some lean years. Passenger traffic rose from 50,000 at the end of 1962 to just 2.5 million in 1975—this at a time when 11.7 million travelers were passing through National. Even in the mid-1980s, traffic at Dulles hovered only at about the 10-million mark. Not until the 1990s, when the main terminal was expanded—according to Saarinen’s own plans—and midfield concourses were added did Dulles come into its own, with traffic reaching nearly 20 million a year by the end of the decade. Of those, more than 3½ million were international travelers.

Only recently, then, has Dulles fulfilled the promise of its creators. Airport officials predict that 55 million passengers a year will soon travel through Dulles. The recently opened AeroTrain system, which shuttles travelers from the main terminal to the midfield concourses, has made the mobile lounges largely obsolete. And the Metrorail extension now in the works will provide easier access to the airport—hardly a novel concept, given that as far back as 1962 transit officials had proposed an elevated high-speed rail line from Georgetown to the airport.

Dulles was designed to accommodate the world’s largest jets. But who could have imagined during those early days the scene on a warm June day this year, when Air France Flight 28, the superjumbo Airbus A380, touched down for the first time in Washington? It was a clear afternoon, perfect flying weather, and as the world’s largest passenger airliner, with seating for more than 500, taxied to gate A22, fire trucks gave a water-cannon salute and workers at the airport stopped to snap pictures, the entire field abuzz, as it was on that first day in 1962.

Some of the passengers arriving from Paris would have likely noticed something else that day: the modernist terminal receiving them. And if those people were forming “an impression of our country,” as Kennedy predicted in 1962, those of us who love Saarinen’s sleek masterpiece would have hoped that the impression was, in the President’s words, “the best.”

This article appears in the December 2011 issue of The Washingtonian.