In his three years on this earth, Jesse had pretty much devoured it. Thai, Indian, Salvadoran, Vietnamese, Afghan, Cuban, Greek, Turkish, Ethiopian, French, Brazilian, Portuguese, Japanese, Chinese, Armenian, Peruvian, Bolivian, Kazakhstani, Bosnian–there was nothing he hadn’t tried. The list of foods he loved and asked for was long: edamame and mango lassi and chicken tikka and char siu bao and grilled stuffed grape leaves and kanom jeeb and chicken curry puffs.

He made the other kids from the parents’ group look like pikers. He made me look like a piker. I had been writing professionally about food for a decade but had never tasted many of these things until I was in my mid-twenties.

Was there a correlation between trying so many kinds of foods at such a tender age and becoming a richer, more broad-minded person? I liked to think so. Jesse wasn’t being dragged out to dinner night after night at Daddy’s whim, I told my wife; he was getting an education. And what an education it was. You couldn’t buy an education like this.

As I made this point one night in the car after restaurant visit number 872–the third night in a row I had kept him out two hours past bedtime as I worked feverishly to finish my work for a dining guide–Jesse, giddy with tiredness, was belting out songs in the back as if he’d just discovered Ethel Merman on YouTube.

“Daddy? Sing?”

“You like to think you’re the guide, in control,” a friend with two kids in their twenties told me. “But you’re not. All you can do is direct them a little. You’re not the bike. You’re more like the training wheels. And what you have to remember is eventually the training wheels come off.”

We were on our way to restaurant visit 924 when my son pointed out the pair of golden arches looming ahead.

This is what’s commonly referred to as a teachable moment, a chance to put forward a philosophy of food and, in this way, install a belief system that will last a lifetime.

“It’s not yucky,” he said and then, gathering himself, uttered the words with an almost sinister deliberation, driving the dagger in more deeply: “McDonald’s is delicious.”

“McDonald’s,” I said, “is yucky.”

“It’s not yucky,” my son replied.

“Ick,” I said. “Ugh.” I shuddered.

Jesse became agitated, thrashing against the constraints of his car seat. He was crying. “It’s not yucky,” he said and then, gathering himself, uttered the words with an almost sinister deliberation, driving the dagger in more deeply: “McDonald’s is delicious.”

It required every ounce of concentration on my part not to hit the car in front of me.

It required every ounce of concentration on my wife’s part not to burst out laughing.

“How’d this happen?” I demanded. “Did someone take him to a McDonald’s? One of the babysitters?”

Silence. A guilty silence.

“I mean,” my wife said cautiously, “he’s had fries a couple of times.”

“You’ve taken him for fries?”

“A couple times.”

“A couple–“

“Okay, a few. Maybe a burger once or twice.” She winced, cutely.

“How could you?”

Number 1,000 loomed, a figure I’d been pointing to for nearly a year. But it seemed ridiculous now, all that number-keeping. All that striving.

“He’s three, you know,” my wife said.

“I know.”

“Do you?”

“What are you saying?”

“He just enjoys being with you.”

My son had had a rough week: two doctors’ visits, an upset stomach, and–either because he’d just turned three or because the gods had decided to complicate our life even more–a growth spurt that made him cranky. I hadn’t been around much, having been cramming in final visits to several restaurants before an upcoming family trip.

That Saturday, I decided, would be Daddy-and-Jesse day.

“Aww,” my wife said. “He really could use some Daddy time. What’s the plan?”

I told her.

“You mean,” she said, “you plan to take him to work with you.”

“No. To dim sum.”

“You’re sure about that.”

“He loves dim sum.”

“I meant you’re sure this isn’t work? This isn’t a place you’re reviewing, or checking up on? What’s the restaurant?”

I told her.

“I’ve never heard of it.”

“It’s new.”

“Uh-huh,” she said. That tone again. “Just try to have a good time, okay?”

It was noon when we arrived for restaurant visit 1,027. The place was a scene of happy chaos. Extended families huddled around big circular tables with lazy Susans, servers dashed through the room like rush-hour commuters in pursuit of a departing subway train, the hawkers with their metal carts circled in search of a sale, lifting lids and sending up little clouds of steam.

Our table was a scene of happy chaos, too. Steamed pork buns and roast pork buns. Shrimp dumplings and shrimp balls. Rice-noodle crepes stuffed with shrimp and stuffed with ground pork. Tiny custard pies and pineapple buns for dessert. I don’t think I had ever seen Jesse eat so much at any one meal. For a feeder descended from a long line of feeders, there’s nothing quite as gratifying as seeing someone you love eat with gusto.

Somewhere between the shrimp balls and the shrimp noodle crepes, my wife texted me: “How’s it going?”

“He’s loving it,” I wrote back. “He looks relaxed and happy, and he’s eating like someone who hasn’t seen food in a week.”

“I’m glad he’s getting his fill. He loves being with his daddy.”

A triumph.

Back home, I couldn’t help myself. Before I had unstrapped the diaper bag from my shoulder, before I had helped him out of his shoes, before I had even stepped ten feet into the house, I began exulting. I was dangerously skirting the line of gloating. There were, I said, all sorts of ways to have a good time and all sorts of venues. It didn’t always have to be a zoo, a park, a playground. He could come into our world, I said; we didn’t have to go into his.

“I’m glad it went so well,” my wife said, walking into the living room only to be crushed by my son’s running, lunging hug.

“Amazingly well,” I corrected.

“Jesse, did you have a good time with Daddy?”

For the next ten minutes, as my wife helped him into a new set of clothes and then all three of us went into the playroom, I listened to my son tell the story of the day.

It came in bursts, a little at a time, and what he said wasn’t as interesting as what he didn’t say.

The afternoon, according to Jesse, amounted to the following: Sitting next to Daddy. Eating with Daddy. Blowing bubbles in the water glass with Daddy. Laughing at the waiter with the funny glasses with Daddy. Making the bunched-up straw wrapper into a snake with Daddy.

He didn’t mention a single dish. He didn’t mention any food at all.

My son is up to something like 1,300 visits by now.

I don’t know how many exactly.

My wife and I just had another child, a son, and life is busier than ever.

In any case, I’ve stopped counting.

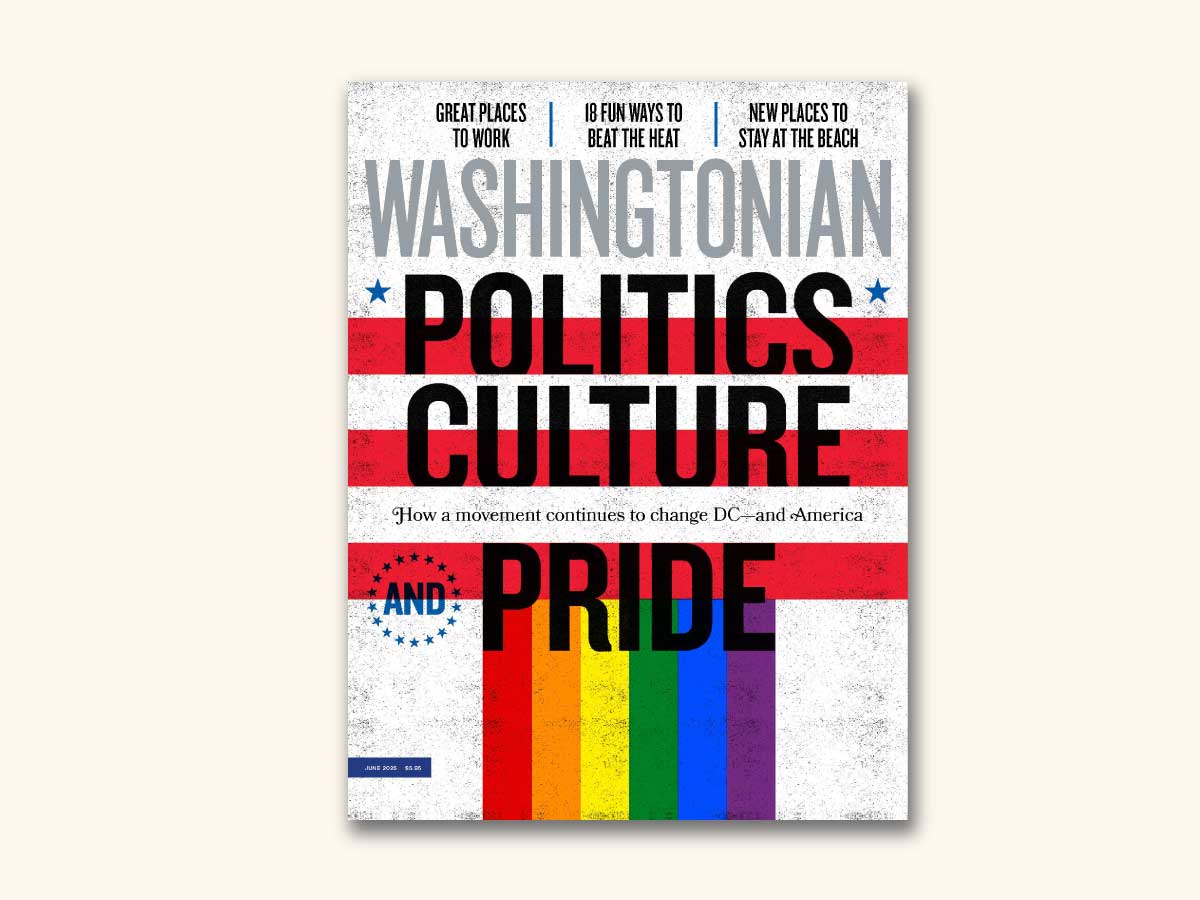

This article appears in the February 2012 issue of The Washingtonian.