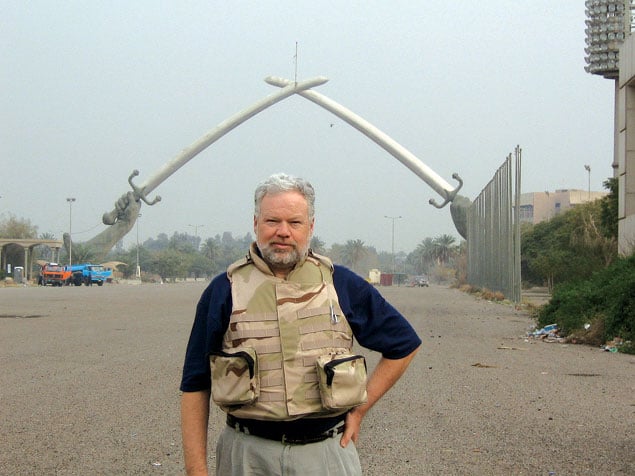

Tom Ricks arrived in a parking lot outside Najaf, Iraq, at the

end of a 36-hour road trip that should have taken a third of that time.

The Washington Post reporter was riding along in a Humvee with

the Army’s 1st Infantry Division, reporting on the movement of thousands

of troops into the central Iraqi city, where Shiite militias had clashed

several times with US forces in previous weeks. It was April 2004, one

year into a war that Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld had doubted would

last more than five months.

During the journey to Najaf, the convoy was shot at with

rocket-propelled grenades and nearly blown up by a roadside bomb. “Don’t

be alarmed,” a 23-year-old sergeant told Ricks, then 48, as the soldier

calmly lit a cigarette, “but somebody here is trying to kill

us.”

The harrowing trek was part of the biggest Army operation in

central Iraq up to that point, and to Ricks it felt portentous. “The US

military operation in Iraq began to feel less like a troubled occupation

and more like a small war,” he wrote in the Post two days later.

Along with some other reporters, he was sensing what military leaders

refused to acknowledge: US forces were facing an insurgency, a campaign of

guerrilla warfare for which the military hadn’t trained and that the

American public hadn’t been told to expect.

“I had really known and admired the US military,” says Ricks,

who has worked the national-defense beat for a quarter century and whose

fifth book, a sweeping review of wartime leadership called The

Generals, comes out this month. “But what was going on in Iraq was

not what I expected.”

The mightiest military in the world found itself literally

mired in mud, stuck in traffic during interminable convoys, shot at by

insurgents hiding in palm groves, and unable to cross bridges that had

been blown up in their advance.

“Jesus,” Ricks remembers thinking. “I’m going to be chained to

Iraq for the remainder of my life in journalism.”

From Najaf, Ricks called his wife. “I just thought you should

know we were bombed tonight,” he told her.

There was something he needed to know, too, she said. That

night, at the same moment the missiles and the rockets were flying,

Ricks’s father had died of a heart attack.

“It was a moment of departure for me,” Ricks says, a confluence

of life-rattling events that permanently altered his perception of the war

and his role in it.

Ricks sat down and wrote, something he does every day, but with

a new urgency. He tapped out an e-mail to Scott Moyers, the editor who was

working with Ricks on a yet-unnamed book about the spiraling Iraq War.

“Scott,” he wrote, “I have a title: Fiasco.”

• • •

Published 27 months later, in July 2006, Fiasco: The

American Military Adventure in Iraq arrived at an opportune moment. A

battle-weary public was primed to hear Ricks’s unsettling message that the

United States was in danger of losing the war.

“The title of this devastating new book . . . says it all,”

the New York Times wrote in its review. Ricks “serves up his

portrait of [the Iraq] war as a misguided exercise in hubris, incompetence

and folly with a wealth of detail and evidence that is both staggeringly

vivid and persuasive.”

Fiasco shook the military and political

establishments. Word went out among some top officials that they should

avoid talking to Ricks lest they end up a character in an unflattering

sequel. It was a blistering indictment, perhaps the strongest of a short

list of books published around the same time that offered grim assessments

of the war.

But Ricks also pointed to solutions, even saviors. He praised

General David Petraeus, then in charge of the Army Command and General

Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, for requiring that the

long-overlooked military theory of counterinsurgency be taught to all

midcareer officers. COIN, as it’s often called, prizes civic engagement

and street-level diplomacy over violent fighting to control territory. The

key to victory is to protect and win over the population, defeating

insurgents not by killing them but by making them irrelevant.

More than any other chronicler of the Iraq War, Ricks brought

COIN to its zenith of influence and credibility in Washington, where

policymakers were desperate for some antidote to the blood-filled slog in

Iraq. Ricks’s book, and later his blog, the Best Defense, became prominent

showcases for COIN theory.

COIN was a gateway for Ricks, the crossover between

dispassionate reporting and writing with a clear point of view. He was

leaving the ostensibly neutral terrain of journalism for a realm in which

he began influencing the same policies and people he’d spent his career

writing about.

“He joined the community he once covered,” says Michèle

Flournoy, a former senior Pentagon official who cofounded the Center for a

New American Security, a think tank that became the COIN brain trust and

where Ricks is now a senior fellow.

On his blog and in newspaper op-eds, Ricks has launched a

frontal assault on cherished pillars of military culture. He has called on

the services to close their prestigious academies and use the savings to

fund college ROTC programs. He has argued in favor of reinstating the

draft.

“The whole Pentagon reads his blog,” says Kurt Campbell, an

assistant secretary of State and former Pentagon official. Ricks has

invited guest posts from experts. Petraeus has been among the blog’s

commenters.

In all Ricks’s work, there is both a writerly verve and an

empathy for the grunt, the human being inside the boots on the ground.

When senior Pentagon officials read Ricks, it may be at least in part

because he’s more in touch with the troops than they are.

• • •

Ricks was introduced to COIN by a retired intelligence officer

named Terry Daly, who suggested that he pick up a copy of the movement’s

seminal text, Counterinsurgency Warfare: Theory and Practice by

David Galula, a retired French colonel who fought in the Algerian War.

It’s the most concise explication of COIN’s core values, based on Galula’s

own battles with insurgents. But it was nearly forgotten by military

historians after its publication in 1964, three years before Galula

died.

Ricks was deeply impressed by the book; he compared Galula to

the revered Prussian military thinker Carl von Clausewitz. Ricks began

recommending the book to an exclusive, off-the-record listserv of

academics, policymakers, and military journalists called the Warlord Loop.

His posts caught the attention of John Nagl, a young Army officer who

would go on to be one of COIN’s most visible proponents.

“I’m embarrassed that I hadn’t read Galula until 2005, when Tom

mentioned it,” Nagl says. Daly was also encouraging members of the Warlord

Loop to study Galula’s work.

In 2006, Nagl joined a committee of experts and scholars

convened by Petraeus to write a new edition of The U.S.

Army/Marine Corps Counterinsurgency Field Manual. The updated

document was infused with Galula’s principles.

In Washington, President George W. Bush and Pentagon leaders

were searching for a new plan of attack. They turned to Petraeus, who had

already held two commands in Iraq, and his dusted-off theories about how

to win a war. In January 2007, Bush announced a “surge” of 20,000

additional troops. Petraeus was put in charge of all US forces, leading

them in battle under the COIN banner.

The field manual made momentary celebrities of its coauthors,

dubbed COIN-dinistas in the press. In August, Nagl appeared in uniform on

The Daily Show With Jon Stewart to discuss the book and the new

way forward in Iraq. A few months later, some of his fellow writers, until

then mostly unknown outside the rarefied zone of military policy, appeared

on Charlie Rose. Petraeus’s followers had a rare combination of

combat experience and doctoral degrees, and they lent immediate

credibility to the new strategy. The manual was posted to the Internet,

and more than 2 million copies were downloaded in two months.

It was remarkable enough that a complex military text based on

an overlooked treatise by a dead French officer sparked a national

conversation about war-fighting on late-night talk shows. But more

important, COIN became the idea upon which hopes for an honorable American

exit from Iraq were pinned. If not for Ricks, it might never have caught

on.

“Ricks brought Galula to a mainstream audience,” says Nagl.

“Repopularizing Galula really was a key idea that underlay the

counterinsurgency insurgency.”

Ricks’s break with traditional journalism was probably

inevitable. For most of his career, which included 17 years at the

Wall Street Journal and earned him two shared Pulitzer Prizes, he

felt hemmed in by what he calls the “bloodless” style of newspaper

writing. A disapproving editor, he says, once admonished him about proper

form in an article.

“Tom, your story doesn’t have a Washington Post

lead.”

Ricks replied, “Thank you.”

Ricks’s War Chronicles

2006

Ricks paints a bleak picture of the Iraq War. The book is published as public support for the war is beginning to wane.

2009

The author praises General David Petraeus and argues for the use of counterinsurgency strategies in Iraq.

2012

Ricks studies nearly 80 years of Army decision-making to explore the theme of accountability of leadership.

Ricks was born in Massachusetts in 1955 and grew up in New York

and Afghanistan, where his father, a professor, worked for two years in

Kabul. Ricks spent his early teenage years riding buses from town to town,

learning enough Farsi to hold a conversation and trying to visit every

Afghan city with a population over 5,000. He says he made it to all but

one.

Ricks and his wife, Mary Kay—also an author—have two adult

children and split their time between a home on Capitol Hill and one on an

island off the coast of Maine. Ricks says that when he was writing

Fiasco, he rented a house in Maine for three weeks and found that

in the remote setting he was especially prolific: “I was writing like a

monkey.” He rented a house again while writing another book. His wife told

him that for the money they were spending on vacation rentals, they might

as well buy a house there.

Ricks left the Washington Post at the end of

2008 after eight years. He’d been thinking of quitting to write books

full-time, and when the paper offered buyouts, he says, “I leapt at it.

Going to the Post was one of the best decisions I ever made.

Leaving it when I did was another good decision.”

Ricks had chafed at the newspaper bureaucracy, and he was

disappointed by editors who resisted embracing the Internet as a new

opportunity for publishing. “The newspaper business model was optimized

for 1920,” Ricks says. “My frustration with the utter failure of

newspapers to really recognize how the world was changing sensitized me to

failures in the military.”

He started blogging soon after he left. His former editor,

Susan Glasser, had taken over as editor-in-chief at Foreign

Policy magazine, which the Post had bought. She asked Ricks

if he’d like to reprise a feature she had overseen for the paper’s Outlook

section, called Tom Ricks’s Inbox, which gave readers snippets of e-mail

conversations Ricks was having with sources and experts about the wars in

Iraq and Afghanistan. Ricks’s blog, the Best Defense, drew an audience of

high-level officials and influential thinkers and won a National Magazine

Award in 2010.

In 2009, Ricks came out with his follow-up to Fiasco.

With The Gamble: General David Petraeus and the American Military

Adventure in Iraq, 2006-2008, he started making predictions. In

speeches and on TV and radio, he said that American troops would be in

Iraq for another ten years. And he took sides. Petraeus was cast as a hero

of the war effort, aided by his COINdinista acolytes.

Ricks sometimes hands his blog over to guest posters who are

critical of his work and of COIN. Others have faulted him for giving

inordinate weight to the strategy, which they say hadn’t been sufficiently

studied or tested in war. Recently, new figures that weren’t available

during the Iraq surge have raised doubts about whether an influx of troops

and COIN principles was what caused the drop in violence in 2007 that

paved the road to an American exit. Scholars now question whether other

events, such as Sunni tribal leaders’ siding with US forces in a mutual

struggle against al-Qaeda, had a bigger effect.

Critics also argue that COIN theory, as described by its

proponents, was never actually implemented in Iraq, nor has it been in

Afghanistan. The military strategy in those countries has drawn on some

core counterinsurgency principles, but US troop levels have been too low

to sustain the kind of broad civil pacification that Galula saw as key to

winning hearts and minds. The US military strategy also didn’t eschew

violence; many of the significant strategic victories against insurgents

were the result of targeted operations to kill key members.

Ricks has said the Iraq surge failed to change the political

dynamics in that country, and now he says the increase in troops was the

“least important” military factor in Iraq. As for COIN, he looks back with

a remarkably different view.

“I think it became a convenient handle for everyone to pile on

about how we should change what we’re doing in Iraq,” Ricks says, not

exempting himself or anything he wrote. “I think COIN was a very good

tactic for what Petraeus was trying to do in Iraq, which was to extract us

with dignity, which he did. Now COIN isn’t the flavor of the month, but it

worked for the time.”

Blogs such as Ricks’s have provided a forum for hashing out

competing theories of war-fighting. That has been a vital exercise, but it

has also produced some half-baked theories.

“The Internet has opened the door for vacuous but cute, concise

ideas to lead the debate,” says Celeste Ward Gventer, a former senior

Pentagon official who served two tours in Iraq and provided policy advice

on reconstruction and counterinsurgency to defense policymakers. “[Ricks

is] part of that story because he was one of the people who pushed these

ideas that hadn’t been sufficiently vetted and explored by scholars.”

Washington shares the blame, too, she says. “It’s an unbelievably faddish

town, and COIN was the fad to end all fads.”

But in Iraq in 2006, the military urgently needed to change

course.

“The middle of a war is not the time to sit and wait for proper

academic studies to be conducted,” Ricks says. “I know of no evidence that

academics were studying whether counterinsurgency could be applied in Iraq

until outsiders began urging people to do it. Can you imagine someone

saying that we needed to do an academic study of whether D-Day would

work?”

Ricks doesn’t call himself a historian. Although his latest

book, The Generals, scrutinizes nearly eight decades of Army

decision-making, it’s not precisely a work of scholarship. He uses the

tools of reporting and storytelling to explore a theme that infuses much

of his writing: accountability of leadership. Who’s in charge of a war

matters. But mistakes shouldn’t spell the end of a career. The best

generals learn from them.

Writers are no different.

“I was wrong about the troops in Iraq,” Ricks says. “I thought

we’d have them there for many years to come.” In 2009, when President

Obama was announcing his plans to withdraw US forces, Ricks was one of the

most prominent skeptics; he said American servicemembers would be in Iraq

at least another five years, possibly ten. The last troops left on

December 18, 2011.

“I think I was also overly pessimistic about what would happen

in Iraq when we left,” he says. In 2009, he warned that the country would

fall apart absent an occupying US force. Today he thinks Iraq still hasn’t

solved its long-term problems, but it’s more stable than he had

predicted.

“It has chastened me, being wrong,” he says. “But there’s a

responsibility to make predictions, to say, ‘Here’s where I think things

could lead.’ ” It’s as though, for Ricks, the price of dropping the mask

of journalistic objectivity is never again to hide his true

face.

It turns out that the 25 years he spent working for newspapers

were a prelude to the job he really wanted all along. “I was a writer

trying to be a journalist,” Ricks says. “But now I’m a writer. It feels

like I’m home, like I’ve come into port.”

Senior writer Shane Harris (sharris@washingtonian.com) is winner of the 2010 Gerald R. Ford Prize for Distinguished Reporting on National Defense.

This article appears in the November 2012 issue of The Washingtonian.