The Ward 4 candidate forum at the height of the 2010 mayoral

campaign should have been a rousing affirmation of DC mayor Adrian Fenty’s

first term.

Fenty lived in the District’s Ward 4 and had begun his rise to

the pinnacle of city politics there. Its precincts are home to DC’s

African-American elite in Shepherd Park near the Maryland line and spread

east to the gentrifying neighborhoods of Petworth and Brightwood along

Georgia Avenue. On the evening of August 4, 2010, St. George Church on

16th Street was overflowing. In the parking lot, Fenty supporters traded

taunts with campaign workers for challenger Vincent Gray, the DC Council

chair.

Inside, Sulaimon Brown berated Fenty. A long-shot candidate,

Brown interrupted the mayor, insulted and belittled him. Fenty tried to

fend off the verbal blows. Sweat glistened on his brow. He took off his

sport coat. He slumped at the table. Brown suggested that Fenty “and his

cronies” should serve jail time. The crowd roared with

approval.

Vince Gray eased back in his chair and smiled. Here in Fenty’s

home base, the challenger came off as relaxed, confident, and in control.

He joked with the crowd. He winked at four friends in the front row:

Marion Barry, Cora Masters Barry, Rock Newman, and Sharon Pratt

Kelly.

An underlying theme in the campaign to unseat Fenty was that

Vince Gray would resurrect Marion Barry’s power base, bring back his

machine, and redirect the flow of city contracts to Barry’s friends. Fenty

had tossed many old-guard Washingtonians from his government and its

trough. Encouraged by Barry, they wanted back in. The presence of the

foursome in the front row seemed to confirm that narrative.

Barry had no particular business at the Ward 4 forum except to

cheer on Gray. The former mayor now represents Ward 8 on the DC Council

and lives and works across the Anacostia River.

Cora Masters Barry, his ex-wife, had been his comrade in arms

during his fourth and final mayoral term, and she loathed Fenty for

declining to renew her contract to run a tennis program in

Southeast.

Rock Newman, a successful sports and boxing promoter, had

financed and engineered Barry’s return to politics in the early 1990s

after Barry served a six-month jail term on cocaine charges. Now Newman

had put his money and clout behind Gray.

Sharon Pratt Kelly, who succeeded Barry as mayor in 1990, was a

member of Ward 4’s elite. She despised Fenty as an upstart who ignored

her.

After the forum, Barry, wearing a Vincent Gray sticker, cruised

the crowd. He joshed with Kwame Brown, who was running to replace Gray as

council chair. Brown’s father, Marshall, had served as one of Barry’s top

lieutenants during his first three mayoral terms.

Barry also huddled with Vernon Hawkins, the most direct,

back-channel connection between Barry and Gray. Hawkins had been a Barry

stalwart for decades and served as director of Barry’s Department of Human

Services until a federal control board forced him out in 1996 for

mismanagement. Hawkins had reemerged to convince Gray to run for mayor and

had stayed on as a campaign adviser.

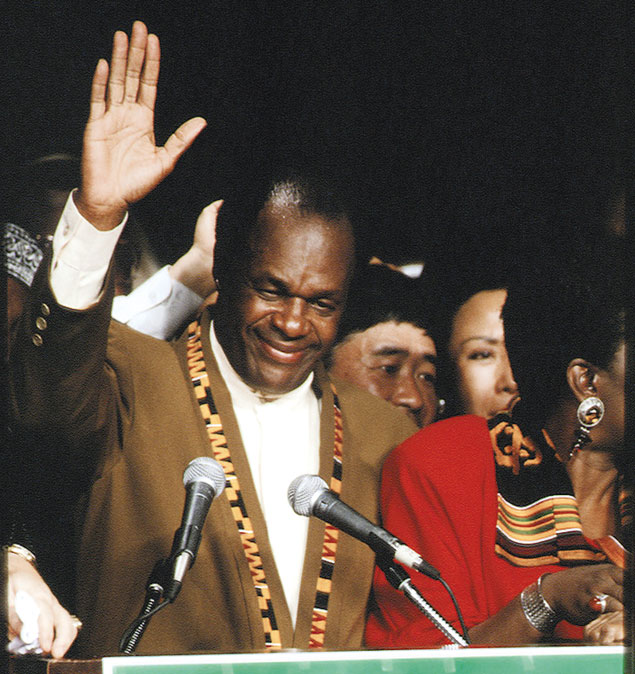

When Gray defeated Fenty in September 2010 and prepared to

become mayor the following January, Barry was in position to wield

citywide power once again. He’d had a hand in Gray’s ascent. He had a

direct line to Kwame Brown, the incoming council chair. Ward 5 council

member Harry Thomas Jr. idolized Barry, who now had close to a working

majority on the 13-member council.

At 74, Marion Barry seemed on the verge of yet another

comeback.

It was not to be.

Instead, Gray’s election and the corruption investigations that

have followed could mark the beginning of Barry’s end.

Scandal dogged Gray as soon as he took office. His top aides

came under fire for stashing friends in plush city jobs. Sulaimon Brown

accused Gray and his campaign aides of paying him to hassle Fenty. Federal

prosecutors have already pinned felonies on three top Gray aides for the

scheme. The ongoing investigation of Gray’s campaign has focused on Vernon

Hawkins for allegedly running a “shadow” campaign that poured more than

$600,000 into Gray’s coffers, off the books.

Kwame Brown was forced to resign after federal prosecutors

charged him with bank fraud. Harry Thomas Jr. was forced to resign for

stealing $350,000 in public funds.

Rather than riding the ouster of Fenty and the reassembly of

his machine into power, Barry now seems alone and exposed, according to

scores of interviews with colleagues, admirers, and critics. The “old

guard” revival passed quickly, raising a question: Is Marion Barry finally

on the road to irrelevancy?

“There’s a reservoir of good will toward Marion,” says at-large

council member David Catania. “But he’s fading in the memory of most

people. Since 2004, when he came back to the council, what milestone piece

of legislation can you attribute to his singular advocacy?”

Says a local politician who has worked closely with Barry for

decades: “His profile is so low, he doesn’t do much harm. He doesn’t raise

the level of discourse; he lowers it. Marion of the civil-rights movement

had passion. I don’t see the passion in the brother anymore.”

Says John Tydings, a veteran business leader who befriended

Barry in the early days and supported his rise: “Marion led us into the

environment that violating the public trust is allowable and acceptable.

That’s awful. Kwame Brown and Harry Thomas have to be forgiven. There’s no

accountability, thanks to Marion.”

When Barry arrived, DC was nearly 70 percent African-American.

Thousands of new residents have since moved in, and last year the city was

about 50 percent black. To many newcomers, regardless of race or class,

Barry is a curiosity rather than a serious politician—more pathetic than

heroic.

“Marion thrived when race was a central issue,” says Catania.

“Afrocentricity is less omnipresent. That’s not where we are right now.

Washington is more of a multicultural city.”

A lot of Washingtonians share that view, though many

African-Americans are unwilling to state it publicly.

“The man is tired, and his memory is fading,” says a retired DC

cop who remembers the vibrant mayor who helped integrate the department.

“It’s sad to see.”

“He further divides a town that’s trying to grow up and become

a major metropolitan city,” says a successful African-American

businessman. “He’s hanging around too long. I’m not disappointed in

Marion; I’m disgusted he’s still around.”

Barry likely will be around for another four years. He won the

Democratic primary in April to represent Ward 8 on the city council for a

third term. On November 6, he’s all but assured of winning the general

election.

“Marion is perhaps the best manifestation of a survivor I have

ever seen,” says Catania, who can swing from derision to worship when

talking about Barry.

Though Barry can come off as a punch-drunk fighter who mumbles

and dribbles coffee on his tie, he can still be larger than life—and

virtually ubiquitous. He tweets. He puts holds on city contracts. He gets

media attention when he issues the occasional racist remark, most recently

about Asians who run “dirty” stores in his ward.

Lost to many of DC’s new arrivals is the fact that Barry was

once a great leader. No one since Pierre L’Enfant has changed and shaped

DC as Barry has. If he serves another full term, Barry will have been a

dominant force in Washington for 52 years. The mark he’ll leave on a major

city will eclipse that of legendary mayors such as New York’s Fiorello

LaGuardia, Frank Rizzo in Philadelphia, Richard J. Daley in Chicago, and

Baltimore’s William Donald Schaefer.

Barry has often described himself as a “situationist”—adapting

to whatever situation confronts him. How will he handle his current one,

which finds him losing power on the council and struggling to make ends

meet?

He’s spending much of his time tending to his legacy—and

rewriting history along the way. In speeches and newsletters, he’s taking

credit for things he was responsible for only when showing up to cut the

ribbons. He calls himself the “job czar” in a ward where nearly a quarter

of the residents are unemployed. He has adopted the “mayor for life”

moniker bestowed as a joke by Washington City Paper columnist Ken

Cummins in the 1990s. His summer newsletter, the Liberator,

paints Ward 8 as a garden spot.

Barry is so intent on promoting his version of Ward 8 that he

has contracted with a film company to make a documentary about it. Barry

paid $12,000 in public funds to May 3rd Films for the 30-minute movie. The

same company made a pilot for a reality show about Barry called Mayor

for Life. No one picked it up.

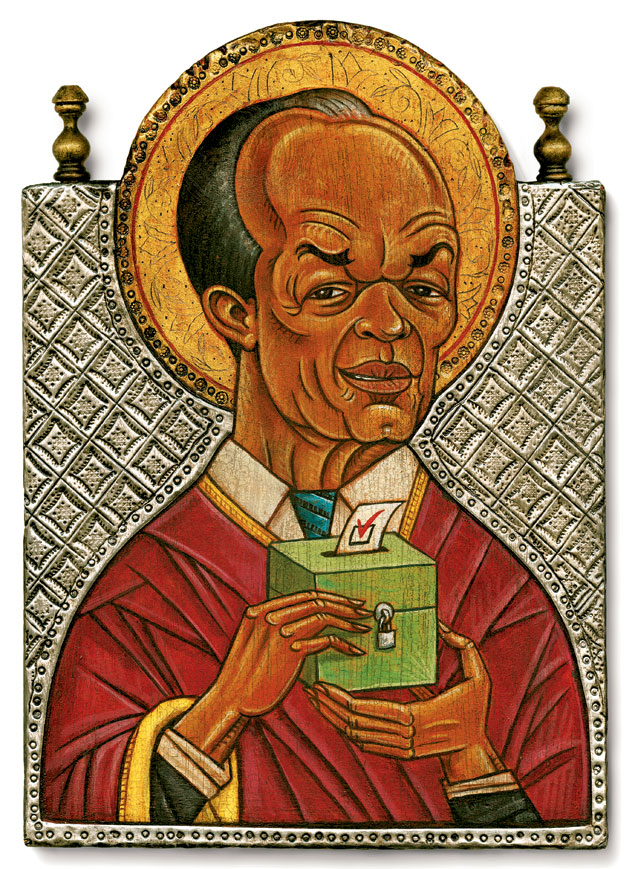

“Marion’s current pathology is that he wants to resurrect

himself as a holy man who brought us to the Promised Land,” says a close

adviser. “He’s on a one-man crusade to make himself Saint Marion. It’s

sad.”

“Marion is bordering on delusional,” says Phil Pannell, a Ward

8 activist, executive director of the Anacostia Coordinating Council, and

a DC school-board candidate.

The terrible paradox, in the eyes of many political and policy

leaders, is that the residents of Ward 8 who keep electing Barry have

suffered the most with him as their political leader.

Says Pannell: “They would elect him from the

grave.”

Barry is still confoundingly popular. A recent Washington

Post poll found that he had the highest favorability rating—52

percent—of any city politician.

Why do people love him so?

“He gave me my first job—at Pride Inc.” says Benny Barnes, who

now works the security desk at a downtown DC office building. Pride Inc.

was a nonprofit Barry created in 1967 to put jobless blacks to work as

street cleaners. “I was 20. He treated us like the vanguard for people

coming behind us. He was an inspirational guy.”

It sometimes seems as if Marion Barry gave more than half of DC

residents their first job, if not through his summer youth program, then

directly on the city payroll.

I asked Vincent Cohen Jr., now principal assistant to US

Attorney Ronald Machen, whether Barry had been an influence in his life.

Not really, he responded. Barry was more of his father’s

generation.

“He did give me my first job,” says Cohen, 42. “It was a

summer-job program. We were baby journalists, writing journals in the

Sursum Corda neighborhood, on the back side of Gonzaga High. My dad made

sure I took part in it. Great job. My first paycheck.”

Kenyan McDuffie, who won a recent election to fill Harry Thomas

Jr.’s Ward 5 council seat, at first says Barry had minimal sway on his

early life. He then acknowledges his jobs in Barry’s summer youth

programs. And his time in the Mayor’s Youth Leadership

program.

Barry bestowed jobs. He also remembered your name. Your mama’s

name. Where you went to school. Where you voted. He also, long before Bill

Clinton, felt your pain.

“Marion represents the whole black experience for many of us,”

says Denise Rolark Barnes, publisher of the Washington Informer,

a weekly based in Congress Heights. “We’re not supposed to make it. But

Marion Barry has, in spite of all his troubles and obstacles. Drug

problems? Women problems? Problems with your kids? Tax people after you?

Tickets on your car? Those are things many of us can personally relate

to.

“Plus,” she adds, “Marion takes time with people. He stops. He

talks. He listens.”

Benny Barnes listened to the young Barry bark orders to his

Pride Inc. street crews in 1967.

“He was rough on you,” Barnes recalls. “He said we had to set

good examples. He showed you how to carry yourself so you could achieve

things, that we weren’t just hustlers hanging out on street corners. There

were other ways to get ahead.”

Barnes carried Barry’s words into the Army and a tour in

Vietnam. Don’t hold back your skills! Come out of your shell! Be proud of

yourself!

“He gave me self-confidence,” says Barnes.

In a sense, Barry did that for DC’s entire black community

through jobs, contracts, and his ability to connect with

people.

“African-Americans have seats at the table at the highest

level,” says A. Scott Bolden, managing partner of the DC office of Reed

Smith, a major law firm. “Marion Barry gets credit for that.”

Washington had never experienced a black man the likes of

Marion Barry. When he arrived in June of 1965, the nation’s capital was a

slow-moving, segregated Southern town.

Three federally appointed commissioners managed the city.

Residents elected no local officials. None. Blacks were essentially barred

from city hall. The police department was white. The Board of Trade, all

white, controlled business through ties to Congress.

President Johnson made self-government for DC part of his

civil-rights crusade. He established an appointed city council and an

elected school board in the 1960s. But it wasn’t until 1973 that Congress

passed the Home Rule Act, giving the city an elected mayor and a 13-member

council.

African-Americans in DC weren’t politically organized. Many had

stable, low-level government jobs. Black leaders such as Walter Washington

and Sterling Tucker were smart but passionless.

Barry was the opposite: brash, demanding, and “militant.” He

alternately dressed in a dashiki—the garb of African nationalism—and a

dashing white suit and Panama hat. Using tactics from the student

civil-rights movement, he was the first person to attempt to organize and

lead blacks in DC, especially the poor population.

Barry was born March 6, 1936, in Itta Bena, Mississippi, the

son of a sharecropper. He excelled in school and went to Fisk University

in Nashville in 1959 to study chemistry and then entered a doctoral

program at the University of Tennessee. The student civil-rights movement

swept up the budding chemist. Barry was briefly the first chairman of the

Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

He wasn’t considered a devoted leader of the movement, like

John Lewis, Stokely Carmichael, or Robert Moses. He was more polished at

public relations. He was dispatched to New York and then DC to run SNCC’s

office here.

Barry’s analysis of DC, typed on carbon paper shortly after he

moved here, was brilliant. He quickly assessed the fault lines of power

among the white ruling class, the compliant black middle class, and the

simmering black underclass. In the next decade, he would organize the

poor, curry favor with white liberals and developers, and leapfrog the

black middle class to political power.

In early 1966, he founded Free DC, a group that he used for

holding press conferences. He called out villains. Businessmen became

“money-lord merchants.” Police were an “occupation army.” The feds were

“congressional overlords.”

After the 1968 riots, DC’s white establishment saw Barry as a

peacemaker, a bridge to the angry black community. He had already helped

establish Pride Inc. with federal grants. He had begun to develop

relationships with white liberals in business and government.

Barry ditched his dashiki and morphed into a politician. He

successfully ran for school-board president in 1971. He accomplished

little but used the post to run for a seat on the first city council under

the Home Rule Act. He won and became chairman of the finance-and-revenue

committee. He sported dark suits, silk ties, and black

loafers.

Ten years after vilifying businessmen, Barry was courting

developers for campaign cash. In return, he used his committee to hold

down business taxes.

The transformation from the streets to the suites was

complete.

In 1978, DC’s second mayoral race under home rule, Barry eked

out a win by 1,500 votes, thanks in large part to six endorsements from

the Washington Post, back then a bible for DC’s liberal

whites.

It was a moment of hope for a biracial, integrated city and its

government.

It was not to be.

Barry and his adviser Ivanhoe Donaldson, the principal

architect of his political rise, focused their energy, power, and money on

the African-American community. In hiring, contracting, and appointments

to city boards and commissions, Barry favored blacks. He bestowed tax

breaks and city grants on black churches. He promoted blacks in the police

and fire departments.

“You went from blacks not having any jobs or contracts to

having opportunities throughout the government,” says Doug Patton, a

lawyer and lobbyist who worked on Barry’s first mayoral campaign. “Marion

brought a sense of entitlement. For blacks, it was ‘my turn.’

”

Barry attracted competent city managers, especially in his

first two terms. He brought in Elijah Rogers, a star among municipal

managers, from Berkeley, California, as city administrator. Other members

of Barry’s brain trust included Carol Thompson Cole, who would go on to

become a leader in the region’s philanthropy sector; attorney Fred Cooke,

now the go-to defense lawyer for city officials accused of corruption; and

Tom Downs, who later became president of Amtrak.

But even early on, there were hints of trouble.

Ivanhoe Donaldson, whom Barry had appointed to run his

employment-services agency, got caught embezzling city funds, pleaded

guilty, and served a jail term.

Barry earned a reputation for hitting on women and bedding more

than a few. His then-wife, Effi, brushed it off and said, “He’s a night

owl.”

By day, Barry opened downtown DC to white developers, just as

he had broken open the government’s doors to blacks.

With Barry’s blessing, planning director James Gibson set in

motion the real-estate boom of the 1980s. Developers turned downtown DC

into a Monopoly board.

“Back then, Marion was impressive as hell,” says John Tydings,

president of the Greater Washington Board of Trade from 1977 to 2001. “He

understood budget and finance. He was perceived in the commercial sector

as highly talented. He gave comfort to the business community that things

were not going to run amok.”

The essential transaction went like this: Barry would open the

city to commercial developers; he would then use the resulting tax

revenues to hire public-sector workers and expand government

services.

In concept, it worked. In reality, Barry grew a government that

failed to train its workers, provided lousy service, and spewed cash to

contractors who didn’t deliver services. Public schools, public health,

and public safety suffered, especially during his third term, 1986 to

1990.

By then many of the stars who had helped manage the government

in the first terms had left. The black middle class Barry helped create

had moved to Prince George’s County. The real-estate boom of the mid-1980s

turned into a bust.

In 1989, the Washington Monthly published an article

that portrayed Barry’s administration as the “worst city government in

America.”

Crack cocaine hit the nation’s capital around 1980. Homicides

topped 400 a year in the late 1980s as local and Jamaican drug gangs

battled to control the market.

When cops reported the crack epidemic to the police brass and

the mayor’s staff and suggested ways to confront the scourge, they were

brushed off. By the middle of Barry’s third term in 1988, the mayor

himself was under the drug’s spell and losing his grip on the

government.

“It was common knowledge within the police department,” says

retired police lieutenant Lowell Duckett. “It was a crazy

time.”

When former city administrator Tom Downs visited his successor,

Herb Reid, he asked how Barry was doing. Reid said: “If it walks, he f—s

it; if it doesn’t, he ingests it.”

Barry’s arrest at the Vista Hotel by DC cops and FBI agents as

he smoked crack cocaine with a girlfriend on January 18, 1990, shocked

Washington. It also set the stage for a year of racial

tension.

Barry went into rehab and returned, in his words, clean and

clear; he announced at a rally, “Barry is back.” In June, he stepped out

of the 1990 race for mayor. Prosecutors charged Barry with 14 counts, from

conspiracy to possession. The city cleaved along racial lines: Blacks felt

Barry had been set up; whites believed he was getting his due. You could

feel the animosity in grocery lines and at lunch counters.

The tension came to a head during the trial in federal court

that started June 18 and ended August 10. Effi Barry sat by her husband’s

side every day as his paramours testified to trysts and cocaine parties.

Pastor Willie Wilson of the Union Temple Baptist Church in Anacostia

rallied black supporters on the lawn by the courthouse. In the middle of

the trial, Barry and his wife attended a rally with Nation of Islam leader

Louis Farrakhan, one of the most divisive figures in the

country.

The jury deadlocked, black against white. After eight days, it

found Barry guilty of one charge: possession. Though it was a misdemeanor

and Barry’s first drug rap, Judge Thomas Penfield Jackson sentenced him to

six months.

From prison in Pennsylvania, Barry spent hours on the phone

planning his comeback. He was far from finished.

When Barry was released, he moved to Ward 8, clothed himself in

African garb—a kufi cap and a kente-cloth scarf. He talked of himself as a

flawed and fallen man—just like so many neighbors who had succumbed to

drugs. He knit himself into the city’s most downtrodden community, from

which he would mount his return to power.

In 1992, he ran against veteran council member Wilhelmina

Rolark, a fixture in the DC black community. She had stood by Barry during

his troubles. He hit the streets to take her down.

“His premise is that people have short memories and he can keep

playing the race game again and again,” said Ward 8 activist Absalom

Jordan, also a candidate for the council seat. “He says, ‘Look at what the

white man did to me.’ He wants people to forget that for years he was the

white man, he was the law, he was in control of the city when Lorton

[prison] filled up with black men.”

Barry beat Rolark 3 to 1.

Sharon Pratt Kelly was mayor at the time. She had won the 1990

election with promises to clean out city hall with a shovel but she turned

out to be ineffective and unpopular.

“I’ll tell you why Marion’s running,” Ab Jordon said of Barry’s

Ward 8 race. “He wants to run for mayor again in two years. It’s just that

simple.

In 1994, Barry indeed ran for mayor. The city split along

racial lines. He won.

His advice to the white residents of Ward 3? “Get over it. I’m

going to be the mayor for all the people.”

Kelly had run up a $750-million budget deficit. That was bad

enough. When Barry, whom many members of Congress saw as an embarrassment,

won his fourth term as mayor, they essentially took charge. In 1995,

Congress established a financial-control board to run the District’s

finances. It had the power to spend money, reach deep into city agencies,

approve and protect a financial czar appointed by Barry.

In essence, Congress neutered Barry. He became a ceremonial

mayor.

At the end of his term in 1998, Barry announced he was retiring

from politics. For the next six years, he attempted to make money as a

consultant and a lecturer. He couldn’t make a go of it.

In 2004, he surveyed the political landscape and saw an

opportunity again in Ward 8. With shades of his 1992 defeat of Rolark,

Barry beat incumbent Sandy Allen, a close friend and supporter. He took

office in 2005 and promised to focus the city’s resources on his

perpetually poor ward.

It was not to be.

“Even then,” says an adviser, “he was too tired to be

effective. He’s been running on fumes for the past eight

years.”

He’s also been running into problems with the law, tending to

his failing health, and putting his foot in his mouth.

DC cops have been known to overlook his indiscretions and get

him home safely. But he’s had run-ins with other law-enforcement agencies

and the IRS.

In 2002 a US Park Police officer found traces of marijuana and

cocaine in his car, but no charges were filed. Barry said he’d been

framed. Secret Service agents pulled him over near the White House in 2006

for running a red light, arrested him, and charged him with driving under

the influence. Park Police stopped him for driving too slowly and wrote

him up for operating an unregistered vehicle and misuse of temporary

tags.

When Park Police arrested Barry in 2009 for stalking Donna

Watts-Brighthaupt, one of his on-and-off girlfriends, a Park Police

spokesman explained that the arresting officer was a New York native who

didn’t know who Barry was.

In 2005, the IRS charged Barry with failure to pay federal or

DC taxes from 1999 to 2004. Barry pleaded guilty. A judge sentenced him to

three years’ probation. Prosecutors returned to court in 2009 and argued

that he had violated his probation by not paying taxes for years. A

magistrate denied their request to send him to jail.

According to two sources in the city government, Barry is still

paying his back taxes, but his probation ended in March 2011.

At the 2009 hearing, Barry’s lawyer, Fred Cooke, chalked up the

council member’s failure to pay taxes in part to his many maladies: heart

congestion, hypertension, diabetes, renal failure, prostate

cancer.

None of Barry’s legal or health problems deterred him from

running for a second council term in 2008, though. Ward 8 elected him

again. He seemed untouchable.

His sole political setback came in 2010. A special

investigation confirmed that Barry had steered a city contract to a

girlfriend and made her use some of the funds to repay a loan to

him.

On March 2, 2010, the council voted 12 to 0 to censure Barry

and strip him of his committee chairmanships, leaving him powerless on the

council.

After the hearing, Barry sought comfort at Matthews Memorial

Baptist Church, high on a hill in Ward 8. His friends and fellow

parishioners greeted him warmly and cheered him on. But Mike DeBonis, then

writing the Loose Lips column for the City Paper, issued this

verdict: “The Marion Barry system of retail politics—or put more bluntly,

patronage—is dying, if it isn’t dead already.”

Barry’s penchant for giving verbal offense, however, is alive

and well.

In April, shortly after he won the Democratic primary, Barry

came out with this proposal: “We got to do something about these Asians

coming in and opening up businesses, those dirty shops. They ought to go.

I’ll just say that right now. But we need African-American businesspeople

to be able to take their places, too.”

When he tried to apologize, he said: “The Irish caught hell,

the Jews caught hell, the Polacks caught hell. We want Ward 8 to be the

model of diversity.”

He said he had misspoken and should have said “Poles,” but

further damage was done.

Weeks later, Barry complained about “immigrants who are nurses,

particularly from the Philippines,” who, he insinuated, were taking jobs

from “our own nurses.”

The Philippine ambassador called for an apology.

Barry owed his early political success in part to support from

DC’s gay community, but when the council voted on same-sex marriage this

year, Barry warned that the “black community is just adamant against

this.” At an anti-gay-marriage rally, he said: “We have to say no to

same-sex marriage in DC. . . . I am a politician who is

moral.”

Always the situationist, he cast the council’s lone vote

against same-sex marriage.

It’s July 10, and the DC Council is holding its final

legislative meeting before the summer recess, an all-day affair starting

at 9:30. Barry shows up at 12:15, strolls slowly across the dais, bends

down to peck Ward 3 council member Mary Cheh on the cheek, and settles

into a chair close to the floor. He surveys the room.

“Rod, Rod,” he says, cocking his index finger and beckoning Rod

Woodson, whose nomination to the DC Water board is in play. They

huddle.

Barry’s hair is gray and fuzzy now. The pants of his pinstripe

suit flap around his legs. His movements seem feeble.

He dispatches Woodson. He sees City Paper columnist

Alan Suderman. He points at Suderman with his index finger. Suderman

sidles over. They whisper.

Barry could get the attention of anyone in the room. In this

chamber—despite the censure, the unpaid taxes, the serial verbal

affronts—he still commands the floor.

But not the dais.

When he was mayor, Barry kept the council under his thumb with

favors. “The Marionettes,” members were called. Now, with Kwame Brown and

Harry Thomas Jr. forced to resign and many colleagues keeping him at bay,

Barry is often a loner. When Brown resigned, the council had to choose an

acting chair among the four at-large members. Barry lobbied hard for

Vincent Orange, appealing to his African-American colleagues to vote for a

black chairman.

The council elected Phil Mendelson, who is white.

Barry promoted Orange for the number-two, pro tempore post on a

second vote. He lost again.

Barry has begun to exercise the power of one. When he was

mayor, the legislative body passed a law that any council member could put

a hold on any contract over $1 million. It was a way to curb Barry’s

power. Now it’s about the only device left in his political tool belt.

Barry puts holds on contracts for reasons that leave his colleagues

scratching their heads. He supported construction of a streetcar line

along Benning Road and H Street, Northeast, but placed a hold on the

design contract until he got commitments that doing so would create jobs

in DC. Council member Mary Cheh said Barry could have raised his concerns

in hearings and was pulling “11th-hour shenanigans.”

“He gets press,” says one council member, “but I’m not sure he

ever accomplishes anything.”

“In the past three years,” says Elissa Silverman of the DC

Fiscal Policy Institute, which advocates on behalf of the District’s poor

population, “I can’t think of one thing Barry has championed to help poor

folks. He’s not a reliable vote for us. He doesn’t bring his colleagues

along. Economic development? Bringing jobs to Ward 8? I can’t think of

anything he’s done there, either.”

Georgenes Restaurant on Martin Luther King Jr. Avenue has been

Congress Heights’ only bar, restaurant, and gathering place for

decades.

On a Wednesday in mid-August, Marion Barry was conducting

business from a booth. Papers were spread across the table. His press

secretary, LaToya Foster, faced him. Both had cell phones on their

ears.

“Mr. Mayor,” I asked, “how about that interview?”

“Not now,” he mumbled.

The interview I had requested for this article would never take

place.

Barry was preparing for the Democratic National Convention—he’s

been a delegate since 1972. He had put a hold on a $4.5-million

construction contract for renovation of St. Elizabeths hospital. He said

he wanted to wring concessions for more jobs. He would release the hold a

few days later with no discernible deal.

For lunch, Barry had the rib tips and greens. Water, no beer.

No dessert. He doffed his Panama hat and walked gingerly through the red

door into the hot afternoon.

He could have been heading home. He lives in a tidy brick house

not far away on Orange Street. Down the street are boarded-up apartments,

rundown houses, and subsidized rental units.

“He’s here all the time,” Georgene Thompson told me. “Always

with a different woman—not always one he works with.”

On that score, Barry at 76 hasn’t changed from the man at 56.

He often has a woman on his arm, whether he’s at Georgenes, having supper

on Eighth Street, or celebrating the reopening of Tony and Joe’s

restaurant in Georgetown, where he grabbed the microphone and tried to

sing before skipping back to a table with female friends. At the

Democratic convention in Charlotte, Barry had to be helped across the

floor in a wheelchair, but he turned up at a hotel bar at 11:30 one night

with a woman on each arm.

Georgenes is located in the middle of a ward that’s been

through many cycles and now sits on the precipice of another: A few

hundred yards down Martin Luther King Avenue, the federal government is

building new headquarters for the Department of Homeland Security and the

Coast Guard. They’re the biggest federal construction projects in the

nation.

In the decades before the 1950s, Anacostia was home to middle-

and working-class whites, many of them first-generation Washingtonians.

Irish, Jewish, and Greek immigrants grew up together. Anacostia High was

all white. The oldest Jewish cemetery in DC is on Alabama Avenue. Blacks

were a small minority.

But in the last 50 years, Anacostia has become home to

Washington’s permanent underclass. Ward 8 leads the city in violent crime,

infant mortality, and unemployment, which stands at 22.5 percent. Nearly

half the children live in poverty.

These statistics applied in 1978 when Barry was first elected

mayor, in 1992 when he was first elected Ward 8 council member, in 2004

when voters elected him again, and now in 2012.

Marion Barry touts the “new Ward 8” every chance he

gets.

“We in Ward 8, under my leadership, have made tremendous

progress in providing countless job opportunities, affordable housing,

home ownership,” he writes in the Liberator, his newsletter.

“We’ve spent billions of dollars on health care. We’ve given Ward 8 a

facelift—changing the physical look from extremely negative to extremely

positive.”

Indeed, things are beginning to change. Old Town Anacostia,

near the Anacostia Metro stop, has new stores, and city-government offices

have set up shop on Good Hope Road. There are pockets of new housing. The

city has demolished notorious housing projects. The ward now has a Giant

supermarket.

“Marion takes pride in taking people around Ward 8, showing

them the new IHOP and Giant,” says Denise Rolark Barnes. “But I don’t know

how much credit he can take for any of the improvements.”

Other city leaders have done much to turn Ward 8 around, with

or without Barry.

Mayor Anthony Williams, Adrian Fenty’s predecessor, promoted

new housing developments. He started moving city agencies across the

Anacostia River. His government encouraged development of the shopping

center around the new Giant. His plan to relocate the Department of

Housing and Community Development came to fruition under

Fenty.

It was Fenty who crusaded for rebuilding and reforming the

city’s public schools, an effort that has resulted in millions of dollars

in improvements to Ward 8 schools.

When it came to reviving United Medical Center, the ward’s only

full-service hospital, it was David Catania, not Barry, who came to the

rescue.

And it was DC’s congressional delegate, Eleanor Holmes Norton,

who lobbied for years to land the DHS and Coast Guard projects on federal

property that was the campus of St. Elizabeths. She has held countless

community meetings, and she monitors the hiring practices of the

contractors to try to get jobs for DC residents.

Barry’s role has been to complain about the lack of jobs for

his residents. He calls himself the job czar, but has he created any jobs

or job-training programs?

“We simply do not see it,” says Ward 8 activist Phil

Pannell.

Therein lies the problem.

With the man in eclipse, the city thirsts for a new leader. A

Cory Booker? Someone like Philadelphia’s Michael Nutter or Chicago’s Rahm

Emanuel?

Jauhar Abraham might remind you of the Marion Barry of

1965.

Abraham is a rabble-rouser. He speaks for the disenfranchised.

He’s a street activist legitimized by a nonprofit funded by the

government. Barry’s was Pride Inc.; Abraham cofounded Peaceoholics, which

helped broker truces among rival gangs before it ran into criticism over

management and finances.

Abraham wants to take his activism to the political level. He’s

running against Barry in the November general election.

“Marion is selling these people out,” Abraham says of Ward 8

residents. “He doesn’t have answers to fix their problems. He doesn’t have

the energy. What he has is rhetorical skills. He has no real relationships

with these people, but his name is so big, he gets by.”

But for all their similarities, Jauhar Abraham is no Marion

Barry. He lacks Barry’s charisma, his political genius. Barry is truly sui

generis, never to be replicated.

Abraham, 45, has little chance of beating Barry at the polls.

But he was born and raised in Ward 8, and he hopes to rally the poor and

disenfranchised—just as Barry did.

Abraham started out in DC schools, and most of his friends are

products of the system.

“Many of my classmates are either addicted to drugs, in jail,

or dead,” he says. “The one thing we had in common? We went to DC public

schools since the 1970s, when Barry had a leadership role.

“I’m not mad at Marion,” Abraham says. “I love Marion. He just

doesn’t operate in the best interests of his people anymore.”

This article appears in the November 2012 issue of The Washingtonian.