Most people haven’t heard of him. But it doesn’t take long

after a bill gets written for everyone on Capitol Hill to ask: What does

Doug Elmendorf have to say about it?

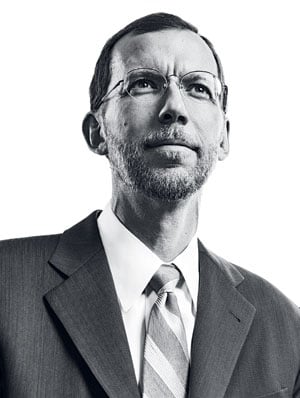

Like his predecessors, the 50-year-old economist toils in

obscurity, despite the power he wields as head of the Congressional Budget

Office. The nonpartisan agency is Congress’s fiscal referee, responsible

for estimating the cost of every major policy proposal or piece of

legislation. Today these estimates—“scores,” as they’re known on the

Hill—carry more weight than ever. Few things doom a bill faster than word

that it would add to the nation’s $16-trillion debt.

But that’s just the half of it.

Congress also looks to this bearded, bespectacled technocrat

for straight talk about where our fiscal policies are taking us, and the

outlook isn’t good.

Elmendorf described the problem in 2009 as “a fundamental

disconnect between the services the people expect the government to

provide . . . and the tax revenues that people are willing to send to the

government to finance those services.” Translation: Americans expect more

from the government than they’re willing to finance.

“I don’t usually get frustrated,” Elmendorf says on the way

back to his office from a recent House Budget Committee hearing. He has

just delivered his direst estimate yet of the nation’s long-term economic

outlook. Judging by the Q&A that followed, the committee registered

little, but he doesn’t seem bothered: “I don’t expect them to be experts

in budgets.”

That’s Elmendorf’s job, and he says he wouldn’t trade it for

anything. He seems to relish the challenge of being the nation’s financial

counselor in chief at a time of rising fear that the US is cruising toward

fiscal calamity.

In the coming weeks, Elmendorf and his staff will be sprinting

to analyze proposals and counterproposals as Congress attempts to address

a two-part problem.

First is the so-called fiscal cliff that looms at the end of

this year. Barring a change in law, the George W. Bush-era tax cuts will

expire and an immediate $100-billion across-the-board reduction in federal

spending will take effect, to be followed later by $1 trillion more. The

spending cut—known as the sequester—was part of a deal President Obama cut

with Congress last year to raise the nation’s debt limit. Many fear that

the sequester and the expiring tax cuts will put the country in a

European-style economic lurch.

To the extent Congress succeeds in extending tax cuts and

delaying budget cuts, odds are that the second part of the problem—a

long-term swell in the national debt—will trigger something far worse: a

loss of confidence in the US economy.

In short, fiscal crisis.

When—or if—that will happen remains a matter of debate, and

Elmendorf is one of very few people in a position to help Congress and the

White House do something to stop it, preventing the global economic

catastrophe that would follow.

• • •

Elmendorf is an economist with a Harvard PhD who introduces

himself as Doug and rides the Metro to work. He answers to Congress but is

about as close to being his own boss as anybody in Washington. Appointed

in 2009 by then-speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi, Elmendorf, a Democrat,

doesn’t play political favorites. His economic judgments regularly offend

and draw praise from both parties.

He was born in Mount Kisco, New York, in 1962 to a father who

was a programmer for IBM and a mother who was a math teacher. He went to

Princeton, where he found himself in orbit with economists who made up the

nation’s financial brain trust.

“I loved my freshman-year courses in economics,” Elmendorf

recalls. His professors Alan Blinder and Harvey Rosen would go on to serve

as top US economic advisers. “They were both fired up about the ability of

economic analysis to make the world a better place.”

During grad school at Harvard, his dissertation committee

included Greg Mankiw, Martin Feldstein, and Lawrence Summers, who served

as advisers to Presidents George W. Bush, Ronald Reagan, and Barack Obama,

respectively.

He also met fellow grad student Karen Dynan, who became his

wife. An expert in macroeconomics and household finance, Dynan is

codirector of the Brookings Institution’s economic-studies

program.

The couple live in Bethesda with their two daughters, both in

high school. They have coauthored several papers, and Mankiw once hired

Elmendorf and Dynan to help write a textbook—it answers questions about

monetary policy in the imaginary economy of Elmendyn.

“I love her because she’s smart, beautiful, charming, and

warm,” Elmendorf says of Dynan. “But it turns out she teaches me a lot

about economics.”

• • •

Elmendorf’s years in Washington have included roles in nearly

every arm of the nation’s economic establishment. He arrived in 1993 to

work at the Congressional Budget Office and later moved to the Federal

Reserve and the White House Council of Economic Advisers. In 1999, he

became deputy assistant secretary of the Treasury for economic policy. He

returned to the Fed in 2001, then moved to the Brookings Institution and

later back to CBO as director.

Such hopscotching would ordinarily be discouraged. “Smart

people mostly focus on something and become an expert on it,” Elmendorf

says. But he had planned to return to CBO, and his broad experience was in

some ways ideal, given the galaxy of legislative issues the agency is

asked to analyze. “It would have been terrible preparation for almost any

job but this one.”

Congress keeps Elmendorf and his staff of 235—mostly economists

and public-policy analysts—running. CBO will pump out 600 written cost

estimates this year and thousands more informal estimates.

On nights when Congress stays up late, CBO stays up later. When

congressional leaders struck a late-night deal on a highway bill in June,

CBO didn’t receive the final version of the 600-page plan until 4 am on a

Thursday morning—less than three days before highway programs were set to

expire and one day before most of Congress was to leave town. CBO returned

its analysis in time for leadership to hammer out an agreement and vote 36

hours later.

Most of the bills that CBO analyzes never become law. Many more

bills are never even analyzed because there isn’t time. Not getting a CBO

estimate can ruin a bill’s chances—even more than being given a hefty

price tag.

It can also get Elmendorf’s phone ringing—with calls from

lawmakers who hope to nudge a bill up CBO’s list of

priorities.

Elmendorf says it’s a misconception that he spends his days

getting yelled at on the phone: “There are people who call who are very

angry—that does happen—but there are also people who call and say thank

you.”

Nevertheless, some of CBO’s answers have sparked epic fights.

The Clinton administration railed against CBO in 1994, when the agency

toppled the President’s signature health-care initiative with estimates

that it would increase the size of government and cost far more than

expected. Elmendorf was part of the team of analysts that rendered the

lethal verdict under then-CBO director Robert Reischauer.

Says Reischauer, who was appointed by Democrats: “If the folks

who invited you to the dance want to drive you home at the end of it, you

haven’t done your job.”

Elmendorf would soon come to know the feeling.

In the spring of 2009, shortly after Elmendorf was appointed

CBO director, a group of former directors took him to lunch. It’s a

tradition at CBO, an opportunity to pass on institutional wisdom and

advice.

“I’m not sure they so much offered advice as just shared scary

stories,” Elmendorf recalls. His takeaway: Should he come under fire or

fail to make his views clear, it wouldn’t be the first time that has

happened to someone in his job.

But what followed a month later was a first for any CBO

director.

The issue—again—was health care. President Obama had begun the

reform effort promised during his campaign. Rather than write a giant bill

and hand it to Congress, as the Clintons had done, Obama put Congress in

charge of drafting the legislation. Early versions of what would become

known as Obamacare began to wend their way through congressional

committees in June of 2009.

On July 16, Elmendorf appeared before the Senate Budget

Committee to testify about the nation’s long-term budget outlook. But

Democratic chairman Kent Conrad wasted no time with his first

question.

“Dr. Elmendorf,” Conrad said. “I am going to really put you on

the spot because we are in the middle of this health-care debate, but it

is critically important that we get this right.”

He asked whether the current versions of the legislation would

reduce the cost of health care over time.

“No, Mr. Chairman,” Elmendorf said. “On the contrary, the

legislation significantly expands the federal responsibility for

health-care costs.”

The answer reverberated across the Hill. With a few sentences,

Elmendorf had upended one of the central premises of the Democrats’

arguments: that overhauling health care would save money.

Some Democrats, who had hoped to have a bill done by the August

recess, fumed. Senate majority leader Harry Reid snapped: “What

[Elmendorf] should do is maybe run for Congress.” House Republican leader

John Boehner said Elmendorf had made clear “that one of the Democrats’

chief talking points is pure fiction.”

Peter Orszag, the former CBO director Obama tapped to lead the

White House Office of Management and Budget, used his blog to say that his

former agency had “overstepped.”

Elmendorf and other experts were asked to come to the Oval

Office to explain their analysis to the President. No CBO director had

ever been called to a meeting with the President at the White House, as

Philip G. Joyce notes in his history of the agency, The Congressional

Budget Office: Honest Numbers, Power, and Policymaking.

Some feared that the summons was an effort to compromise CBO’s

independence and to take Elmendorf to the woodshed. But evidence suggests

it was CBO that forced the President to change course, not the other way

around. As the New Yorker’s Ryan Lizza reported earlier this

year, it was the threat of a costly analysis from CBO that pushed Obama to

backtrack on his campaign’s opposition to the so-called individual

mandate, the legal requirement that people purchase health

insurance.

Obama first publicly flipped on the issue during an interview

with CBS News on July 17, shortly after House Democrats embraced the

individual mandate in their version of the legislation and exactly one day

after Elmendorf gave his explosive testimony.

In fact, Lizza reported, Obama became so frustrated with CBO

during the health-care debate that he banned aides from uttering the

agency’s three-letter name. Instead, the President referred to the agency

as “banana.”

Like his predecessors, Elmendorf seems to take pride in such

episodes. He keeps a plastic banana on the bookshelf in his office—next to

the stuffed skunk that he was given as a reminder of the agency’s

reputation for being the skunk at the picnic.

• • •

Few denizens of Capitol Hill understand better than Elmendorf

how words can be taken out of context—how 30-second sound bites can be

snipped from hours of live testimony and uploaded to YouTube or looped

into the endless cable-news cycle. He walks a verbal tightrope every time

he appears before Congress.

It’s why he spends hours before each hearing in a secret

location—unknown, apparently, even to top aides—with his iPhone shut off

and a stack of binders for a last-minute cram session. He chooses his

words. He considers his explanations. He anticipates

questions.

“They never feel routine,” Elmendorf says of the hearings.

“I’ve done dozens of them now, but the stakes are high. If I get something

wrong, then it can create all sorts of confusion in the

world.”

Former CBO director Robert Reischauer says breaking through the

media and political distortion is one of Elmendorf’s toughest challenges:

“I’m probably the biggest pessimist in town. I think that modern

democracy, mixed with the digital revolution, might be incapable of

addressing these types of issues.”

That seemed to be confirmed during Elmendorf’s June appearance

before the House Budget Committee to address the nation’s fiscal outlook.

There were long-winded questions about Mitt Romney’s economic plan (CBO

doesn’t analyze presidential candidates’ platforms), red-faced anti-Obama

rants, and partisan talking points disguised as questions.

Of particular interest to several Republicans was the 2009

federal stimulus.

According to CBO’s analysis, the $800 billion in government

spending had a positive effect on the economy. Barring some offsetting

spending cuts or tax increases down the road, however, the additional debt

would put a drag on the economy ten years later. Democrats tend to focus

on the first half of that analysis, Republicans on the second.

“So it would be inappropriate to double down in terms of a

failed program?” asked Texas Republican Bill Flores in a typical exchange.

“If . . . stimulus version 1.0 didn’t work, why would stimulus 2.0 work

any better?”

“Well, Congressman, as you understand—and I recognize you don’t

agree with us—but our position is that the Recovery Act was not a failed

program,” Elmendorf said.

For all the debate that day over the 2009 stimulus, there was

comparatively little discussion about the end-of-year fiscal cliff. Or of

real solutions to the long-term debt problem, the “fundamental disconnect”

between tax and spending policies that threatens to drive the US economy

into the ground.

Fiscal-policy decisions made by Congress in the coming months

could mean the difference between a decade or more of economic growth,

stagnation, and decline. Those decisions will be made on Elmendorf’s

watch. Who would want the pressure—or the hours?

Elmendorf estimates that he works 60 to 70 hours a week: “I’m

not proud of that, but there is a lot of work to do. I’d like to see more

of my kids.”

But he doesn’t seem bothered by the pressure. Quite the

opposite. Before the start of the Budget Committee hearing earlier that

day, Paul Ryan, committee chairman and soon-to-be Romney running mate,

bounded over to Elmendorf to shake his hand and pop his usual friendly

question: “Are you living the dream?”

“My answer is yes, I am,” Elmendorf says today. “For somebody

of my interests, I have the best job in Washington.”

Freelance writer Paul Quinlan (paulrq@gmail.com) recently moved from DC to Charleston, South Carolina.

This article appears in the December 2012 issue of The Washingtonian.