It was July 30 and the lease on Shereitte C. Stokes IV’s

apartment in Silver Spring was ending the next day. When a moving company

had failed to show up two days earlier, an exasperated Stokes had searched

the Internet for Maryland companies that could come quickly to ferry his

stuff to Atlanta.

He found Cross State Moving and Storage Company in Rockville,

which estimated that Stokes’s possessions would fill 385 cubic feet and

cost less than $1,000 to haul, he says. Stokes thought he had found a good

deal.

The satisfaction didn’t last long. The crew that arrived

demanded more money than the estimate, saying Stokes had far more stuff

than he had claimed. “Take it or leave it,’’ he says the driver told

him.

Agreeing to the new amount, Stokes watched as the crew added

several charges not mentioned before. After his books, bed, and TVs were

loaded onto a truck, Stokes flew to Atlanta. His stuff didn’t arrive for

nearly three weeks, despite his understanding that the move would take

only days. Stokes still isn’t sure what happened to his computer desk.

Told it broke en route, he never saw it again. Final price for the

aggravation: $2,300.

He and dozens of consumers have filed complaints against

household movers in the Washington area in recent years, as more companies

gather estimates online rather than in person and as more moves are,

unbeknownst to customers, arranged by brokers who work separately from the

moving companies and often advertise online that they can find consumers

the best price. Nationally, 2,800 customers complained to the federal

government in 2011 about household movers, up from 2,400 a year

earlier.

“It’s definitely a problematic industry,’’ says Edward Johnson,

president of the Better Business Bureau of Metro Washington, DC. Many

movers in the area, he notes, “have well-warranted F ratings with the

Better Business Bureau.”

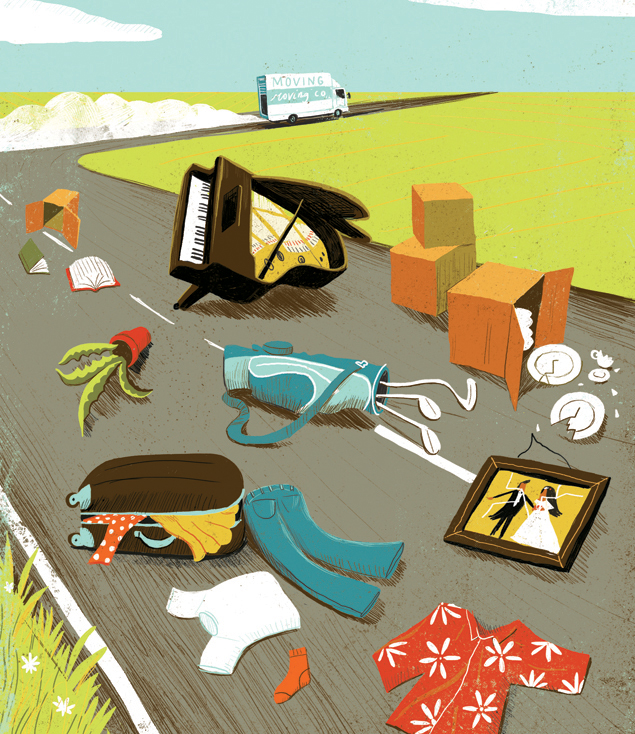

Many customers complain that they were quoted low rates, only

to see those figures double or triple once the movers were at their

doorstep. Others cite shoddy service, broken belongings, and an onerous

insurance process that guarantees that only the tenacious will see money

for lost or ruined items, and then at a fraction of the objects’ value.

When customers try to seek redress with the person who set up the move,

some discover that the initial company was a broker unconnected to the

company that carted away the goods.

Anne Ferro, administrator for the Federal Motor Carrier Safety

Administration, part of the Department of Transportation, says that the

“vast majority” of the nation’s 4,000 household movers are “really good

companies” but that up to 5 percent are rogue outfits that should be shut

down. Her agency’s consumer-oriented website, protectyourmove.gov,

features mug shots of movers wanted by the government.

Some companies say they’re trying to survive in a competitive

industry in which customers demand low prices and will try anything,

including underestimating the volume of their belongings or packing

shoddily to save money.

“If you ask me to move three items and I come and you have 50

items, it doesn’t matter what the estimate says,” says Cesar Bar, Cross

State’s general manager. He says Stokes had underestimated the size of his

move and that the company takes up to three weeks to deliver goods during

summer, the busiest moving time.

Sometimes the problems with movers go beyond

disagreements.

Nearly 600 people complained to the federal government last

year about hostage loads. In this scheme, customers typically get a

lowball bid on the phone. Once the crew has packed a customer’s goods on

the truck, the movers demand cash—as much as three times the initial rate.

If the customer refuses to pay, the crew drives off—the customer’s

possessions held hostage.

The burgeoning problem caught the attention of lawmakers in

2012. Reana Kovalcik, a 28-year-old employee of a New York City nonprofit,

described to the Senate Commerce Committee a nightmare move after she

unwittingly contacted a broker in Chicago through an online search in

2010. The broker dispatched Able Moving, a company that had earned a raft

of complaints online. Able employees loaded the goods and drove off. Days

later, a representative demanded that Kovalcik pay $2,000—more than double

the initial price. She agreed and called the police. Learning that cops

were coming to the delivery address in Brooklyn, the movers took off with

Kovalcik’s things onboard. Her boyfriend tried in vain to tail the movers

in his car as the van circled the city.

Pulled over by police in New Jersey, the movers said Kovalcik’s

items would be unloaded in a Pennsylvania storage facility. But the goods

never arrived. With no idea where they were, Kovalcik resorted to

negotiating with a woman from Able, which turned out to be a shell

company. Desperate, Kovalcik agreed to pay her more than $2,400.

Eventually, Kovalcik and her boyfriend found their furniture and artwork

in a New Jersey storage bin, the majority of it smashed to pieces. The

most expensive items were stolen.

The biggest problem with using brokers is that many aren’t

licensed and ultimately aren’t responsible for the handling of your

belongings or the costs you incur. One of the most discouraging aspects of

Kovalcik’s story was the hope she placed in regulatory and enforcement

agencies. Even though she filed complaints with the Department of

Transportation, the Department of Justice, and the Illinois attorney

general, only a Chicago city agency pursued the case. The agency fined

Able Moving more than $34,000 but has never collected the money or won

restitution for Kovalcik.

“Throughout this process I have been continually surprised and

disappointed at the lack of legal recourse we have had,’’ she told the

committee.

Ferro says the federal government can impose tougher penalties

on brokers and rogue movers—$10,000 per day per violation for holding

goods. The government also can revoke a company’s Department of

Transportation registration number, which allows it to operate across

state lines. In the last five years, the feds have stripped 24 companies

of their numbers.

Before any move, Ferro recommends that consumers arm

themselves.

You should check a moving company’s complaint history with the

Better Business Bureau and with state and city consumer divisions.

Grievances against movers can be found at protectyourmove.gov.

It’s a good idea to get four or five written estimates from

licensed movers and to avoid those who don’t want to visit your house or

apartment before the move.

Movers give estimates that are either binding or nonbinding. A

binding estimate guarantees the total of the move; a nonbinding estimate

approximates the cost—the final price is based either on the actual weight

once everything has been loaded and weighed or on the number of hours the

move takes.

While estimates on moves that cross state lines are based on

weight, local jobs are typically priced by the number of hours needed to

complete them. For interstate moves, it’s especially important to have

movers visit your home beforehand because the insurance coverage will be

determined by the weight.

Consumers should understand the type of liability insurance the

carrier provides. Many movers insure goods at 60 cents per pound, which

isn’t enough to replace household items if they’re damaged or

lost.

Homeowner’s and renter’s insurance may provide limited coverage

for belongings in transit, according to the National Association of

Insurance Commissioners. Movers may offer additional coverage for a fee.

One option is coverage for a lump-sum value rather than the weight. A

consumer must know the value of his or her household items and put it in

writing on the receipt (often referred to as a bill of lading). Full-value

coverage may also be offered; this will pay for the replacement or repair

of lost or damaged property.

Most professional movers don’t require hefty deposits. Scam

movers and Internet brokers frequently ask for large deposits, sometimes

as much as $1,000 to reserve a date. Often these fees go to brokers and

not to the carriers, the Senate committee found. Consider any such request

a red flag.

Know that movers can change a move’s price if additional items

or services not listed in the original estimate are added. (Under a

Maryland law passed in 2011, fees can’t go more than 25 percent above a

nonbinding quote.) Once movers start to load or pack the first item,

though, they’re bound by the original estimate, Ferro says.

Still, savvy people can end up feeling taken. Kate Vincent of

Potomac used three companies for a complex move in 2010. One hiked up the

estimated price by 50 percent, to $3,000, once her items were packed into

pods. After the move, she discovered that several items, including

antiques from her parents, were damaged. Vincent paid $500 for repairs.

She complained to Maryland authorities, including the state attorney

general and small-claims court, but says the volunteer mediator “didn’t

impress me as having any authority or ability to do anything.”

Both Vincent and Shereitte Stokes will know better next time,

and they hope others do, too. Says Stokes: “I think my situation is,

unfortunately, very common.’’

This article appears in the January 2013 issue of The Washingtonian.