Mary Johnson was in bed in the early morning hours of September

21, 2003, when she heard a commotion near the back door. She had lived in

her two-story apartment building in Salisbury, Maryland, for many years.

She figured the noise was just a neighbor moving around.

Then she heard her floor creak.

She sat up and saw a man standing in her bedroom doorway. He

wore a scarf over his face, and the brim of his baseball cap was pulled

down over his eyes. He pointed a handgun at her.

“Shut up and give me your purse,” he said. She did, and then

the intruder knelt on the side of her bed and started to unzip his

pants.

“Please don’t do this,” she said. “Please stop.”

Johnson—whose name has been changed here to protect her

privacy—was 53 years old. She had raised her children and helped bring up

grandchildren in Salisbury, on the Eastern Shore. She went to church,

cared for her mother. For the past 22 years, she had been a clerk in the

Maryland Department of Social Services.

“Shut up!” the man said. “Don’t look at me.”

He put the handgun on her nightstand and raped her.

Johnson managed to kick him off the bed, but he pulled her to

the floor and put the gun to her head. She felt the metal barrel on her

temple.

“Jesus,” she said, “don’t let me die.”

Suddenly he got up, pulled the phone from the nightstand, and

tried to rip the cord from the wall. He left with her purse.

Johnson called her daughter, Doris, who alerted the police.

When two Salisbury cops arrived, Johnson was crying and shaking

uncontrollably. She was able to describe the break-in and rape but

couldn’t describe her attacker. An ambulance took her to Peninsula

Regional Medical Center, where medical technicians examined her for sexual

assault and collected DNA evidence.

Because Johnson couldn’t identify the rapist and there were no

witnesses, police couldn’t make an arrest. Detectives sent the DNA from

the intruder’s sperm to the state crime lab. Technicians obtained a DNA

profile of the suspect and entered it into state and federal DNA

databases, but there were no matches.

For the next six years, Mary Johnson cowered. She hammered

nails into her back door and windows to secure them. She never walked

outside without peering over her shoulder.

The man who raped her was on the loose.

• • •

Salisbury lies 120 miles southeast of DC, a 2½-hour drive over

the Bay Bridge, past flat farmland that once grew tobacco, beyond the

quaint town of Cambridge, almost to the southeastern tip of Maryland. For

Washingtonians headed to Ocean City, Salisbury is a series of stoplights

and fast-food joints along Route 50; the Atlantic is 30 miles due

east.

But Salisbury has a rough side, a history of tense race

relations, violent crime, and persistent poverty. The estimated per capita

income in 2011 was $21,359.

As she boarded the ambulance on the morning of the rape, Mary

Johnson noticed a group of young men under the trees across from her

building. She recognized Alonzo King Jr. among them.

King, just shy of 21, had close-cropped hair and an open,

friendly face. His parents had abandoned him as a child, and he’d been

raised by his grandmother, who lived across the street from Johnson. He’d

dropped out of school after eighth grade.

King had problems with drugs and a juvenile record. He would

later be diagnosed with depression and bipolar disorder.

When he was a kid, one of the few places Alonzo King found

safety and peace was in Mary Johnson’s apartment. King and Johnson’s

grandson were buddies. From the time he was a young boy, King would eat

supper with Johnson, celebrate holidays in her home, hang out after

school.

“Grandmom,” he called her.

• • •

One morning in August 2009, Elizabeth Ireland walked through

the doors of the Wicomico County judicial center in downtown Salisbury,

brushed past the metal detectors, and entered the state’s attorney’s

offices. She reached into her mail slot and pulled out a manila folder

outlining her new cases. One caught her eye: “Application for charges in a

rape case.”

Ireland specialized in prosecuting rape cases. She had grown up

in Salisbury but left for college and law school. She returned to her

hometown in 1987 and landed a job with the state’s attorney. Few women

lawyers were in the courtroom back then, and she was the only female

prosecutor. She tried a rape case her first year.

“It snapped me into focus,” she says. “I felt that justice was

in my hands. How I do that job affects people for the rest of their

lives.”

Ireland has since handled five to ten rape cases a year—nearly

200 over her career as a prosecutor. She didn’t know it that morning in

2009, but this case was headed for the Supreme Court, where it would test

the constitutionality of one of law enforcement’s most powerful tools. It

would have such wide-reaching implications that Justice Samuel Alito would

call it “perhaps the most important criminal-procedure case that this

court has heard in decades.”

At her desk, Ireland called Salisbury detective Barry Tucker

and asked for the police reports. They began with the account of an

assault:

On the afternoon of April 10, 2009, four people were at a gas

station near downtown Salisbury when Alonzo King Jr.

approached.

“Remember that night at the club?” King asked, referring to a

fight almost five months earlier. King then brandished a shotgun. The

group scattered, and one of them flagged down a cop.

Police detained King and searched his car, where they found a

12-gauge shotgun shell in the middle console. They arrested him and

charged him with first-degree assault, a felony.

At the Wicomico County Central Booking facility, a sample of

King’s DNA was taken by swabbing the inside of his cheek. It was sent to

the Maryland State Police Forensic Sciences Division and later analyzed by

a private lab. In July, King’s DNA profile was uploaded to the Maryland

DNA database.

On August 4, 2009, just over four months after King’s arrest

for assault, state police contacted Detective Tucker. Alonzo King’s DNA

matched the DNA in an unsolved rape case from 2003.

After reading the case and talking to Tucker, Liz Ireland

phoned Mary Johnson.

Ireland’s first thought when Johnson walked into her offices

was “not the typical rape victim.” Most of Ireland’s clients were under

age 30; some were in their teens.

Johnson, then 59, was a compact woman, well spoken and quiet.

She wore a simple, dark pantsuit, as if dressed for church.

Detective Tucker had already broken the news to Johnson that

Alonzo King could have been the man who’d raped her six years before. The

shock had begun to wear off.

“She gave off a sense of affronted dignity,” Ireland recalls.

“She was a woman who never imagined she would be sitting in that room with

me having that kind of conversation.”

Ireland didn’t want to discuss the facts of the case at their

first meeting. She didn’t know at that point how close Mary Johnson and

her grandson had been to Alonzo King—that he had called her Grandmom. But

Ireland remembers Johnson describing how she had coped for the last six

years, during which King had remained in her life.

“I’ve tried to live through it strongly,” she said. “I wasn’t

killed. I still have a life and something to live for. But a part of my

life will always be damaged.”

Under the Maryland DNA Collection Act, police have the

authority to take DNA from individuals who are arrested—before they’re

tried—for attempting or committing a violent crime or

burglary.

DNA profiles were introduced in criminal cases in the

mid-1980s. In 1987, Florida rapist Tommie Lee Andrews became the first

person to be convicted based on DNA evidence. A year later, police used

DNA to link a Virginia killer known as the South Side Strangler to a

series of rapes and murders around Richmond.

By 1999, all 50 states, the District, and the federal

government were collecting and analyzing DNA from some convicts. CODIS,

the FBI’s Combined DNA Index System, now holds more than 10 million

profiles.

In addition to helping put criminals behind bars, DNA has also

helped free people convicted of crimes they didn’t commit. The Innocence

Project reports that DNA has helped overturn more than 305 convictions in

35 states and DC.

Maryland passed its DNA-collection law in 1994, allowing the

state to take samples from convicted sex offenders. The law was expanded

in 1999 and again in 2002, to include all felons, and finally in 2008, to

allow DNA collection from arrestees before they’re found guilty. The

federal government and 27 states, including Virginia, have similar laws.

The District does not.

• • •

After Liz Ireland reviewed the King case, she presented

criminal charges to a grand jury. On October 13, 2009, a Wicomico County

grand jury returned an indictment against Alonzo King for ten charges,

including rape, burglary, robbery, and using a handgun in a violent

crime.

The first DNA “hit” couldn’t be used in court, but it gave

Ireland probable cause under the Maryland law to get a search warrant for

a second sample from King. He had pleaded guilty to second-degree assault,

a misdemeanor, for the April 10, 2009, arrest and was serving a four-year

sentence.

Detective Tucker went to the jail with the search warrant,

which specifically mentioned the 2003 rape. For the first time, King knew

he was on the line for assaulting Mary Johnson.

“F— you,” King told the detective, according to Liz Ireland.

“I’m not going to give you anything.”

Tucker phoned Ireland and asked, “What should I do now, Liz? He

won’t give it up, and the jailers won’t hold him down.”

She asked Tucker to try again. He returned to the jail. King

refused.

On November 18, Ireland filed a motion to compel King to submit

to a swab of the inside of his cheek. The judge granted it. Ireland

contacted James Podlas, the public defender representing King.

“I have an order to get the DNA,” she told him. “We are going

to get it, one way or another.”

King relented. Detective Tucker returned to the jail and got

the DNA sample. It matched the first hit.

Ireland read the report: The DNA from the rape was 3.9

quadrillion times more likely to have come from King than from an unknown

individual in the African-American population.

She prepared for trial. If he was found guilty, King could be

sentenced to life. “The case was based on one of the best DNA matches of

my career,” Ireland says. “I knew it would be a case I would not plead

down.”

• • •

Maryland public defenders, meanwhile, saw the King case as an

opportunity to challenge the constitutionality of taking DNA from someone

arrested for one offense and using it to link that person to other,

unrelated crimes. They believe that running an arrestee’s DNA through a

database intrudes on a citizen’s right to privacy under the Fourth

Amendment, which protects against “unreasonable searches and

seizures.”

King’s public defender, Jim Podlas, asked the court to throw

out the DNA evidence. King denied that the first sample came from him, and

his lawyer asked the judge to force Ireland to prove that the DNA had been

properly handled and evaluated by the forensic labs.

Podlas also argued that the state had had no right to take

King’s DNA when he was first arrested. Therefore, Podlas maintained, the

first DNA sample should be thrown out. And because the first hit provided

probable cause for the search warrant to take King’s second DNA sample, it

should be suppressed as well.

In February 2010, Judge Kathleen Beckstead denied the motion to

throw out King’s DNA evidence. A month later, she ruled against Podlas’s

argument that Maryland’s DNA-collection law violated the

Constitution.

Liz Ireland prepared for trial.

She was sipping a cup of coffee at the Barnes & Noble in

Salisbury one day in the spring of 2010 when Jim Podlas

phoned.

“My client will agree to a plea of not guilty on an agreed

statement of facts,” Podlas said. “Will you accept?”

It meant that King would plead not guilty but agree to the

facts of the crime. He would not go to trial but would face punishment. It

was a middle ground that would put him in jail on the rape charges but

also allow him to challenge the constitutionality of taking his

DNA.

If higher courts later ruled that taking King’s DNA violated

his right to privacy, his conviction would be thrown out and he could be

retried without the crucial DNA evidence.

Ireland conferred with the state’s attorney and her colleagues.

For them, the plea was a win: King would face serious jail time, and Mary

Johnson wouldn’t have to endure a public trial.

Ireland called Podlas back and accepted.

• • •

Mary Johnson faced Alonzo King in court on July 27, 2010, for

his sentencing hearing—their first encounter since she found out he was

the man who had raped her.

Johnson walked into the courtroom with her daughter, Doris, and

took a seat behind Liz Ireland at the prosecutor’s table.

King, then 27, sat at the defense table. He was dressed in a

black-and-white prison jumpsuit and didn’t look at her.

The attorneys agreed on the facts of the case, and King said he

understood he was giving up his right to a jury trial. Judge Beckstead

ruled: “The court is convinced beyond a reasonable doubt that the

defendant is guilty.”

After a short recess, Liz Ireland said Mary Johnson wanted to

speak. Johnson steadied herself on her daughter’s arm.

“We took Alonzo in as a family member,” she said. “We fed him;

we knew him as a child. We trusted him. And look what trust

did.

“He is just a cold-hearted rapist,” she continued, “and I do

pray that justice will be served.

“He called me Grandmom,” she said.

Trembling, she looked at King: “If you call me Grandmom, how

can you do that to your grandmother?”

On October 7, Judge Kathleen Beckstead sentenced King to life

in prison without parole.

Stephen Mercer had been waiting for a case like Alonzo King’s

since 2008.

Mercer is the chief attorney in the forensics division of

Maryland’s Office of Public Defender. He oversees how the state’s 570

attorneys who represent indigent clients handle forensic evidence such as

DNA. For Mercer, protecting citizens from what he believes are intrusive

uses of DNA is a crusade.

From his point of view—one shared by civil libertarians—the

Fourth Amendment draws a sharp line at the government’s physical

intrusions into someone’s body to collect evidence of a crime without a

warrant or probable cause. Mercer believes the government broke this rule

with Alonzo King because they took his DNA when he was arrested—but not

yet convicted—for one crime and used it to investigate him for another

that they had no reason to suspect he had committed.

Mercer argues that taking an innocent person’s DNA and applying

it to a database represents a “suspicionless search” and a “fishing

expedition.” He also objects to the government’s collection and storage of

a person’s DNA because of the potential for misuse of the

information.

Rene Sandler, a Maryland defense attorney, poses this scenario:

“Let’s say you’re driving in Virginia and police pull you over because

your car matches the description of a car involved in a shooting. Under

current law, they can arrest you and swab your cheek for DNA. It goes into

the national database. Suppose it matches DNA in an unsolved shooting in a

rental car five years before. You had rented the car and left DNA but had

no connection to the crime. Still, police charge you with that

shooting.

“You were not involved in either crime, and you get off,”

Sandler says, “but only after a costly defense. That might seem

far-fetched, but it’s possible.”

Mercer first challenged the constitutionality of DNA collection

in 2004. He and Sandler represented Charles Raines, who had committed two

robberies in 1996 and was serving time. In 1999, authorities collected a

DNA sample from Raines linking him to a rape three years earlier. Based on

that evidence and testimony from the victim, Raines was indicted for the

rape.

Mercer challenged the use of the DNA as a violation of Raines’s

right to privacy under the Fourth Amendment.

“Maryland’s DNA collection statute violates the Fourth

Amendment precisely because it mandates search and seizure of an

individual’s DNA without any showing of individualized suspicion,” Mercer

wrote in a court filing. “A criminal conviction does not leave an

individual in the state’s custody without a reasonable expectation of

privacy in his intensely personal and information-rich DNA.”

The trial court agreed with Mercer and threw out the evidence,

but the state appealed the ruling to Maryland’s highest court. In a split

decision—4 to 3—the court ruled against Raines, upholding the DNA search

because Raines was in custody at the time his DNA was taken and had

committed felonies covered by the state’s DNA-collection law.

In 2008, when Maryland expanded its DNA collection to include

people who were arrested for violent crimes and burglaries but not yet

convicted, Steve Mercer saw another serious breach of the Fourth

Amendment.

“We were looking for a case that worked its way through the

pipeline,” he says, “so we could challenge the

constitutionality.”

He found his case with Alonzo King.

On October 12, 2010, the Maryland Court of Appeals agreed to

hear King’s case. Mercer helped prepare the argument with the help of

appellate lawyer Celia Anderson Davis.

This time, Mercer’s side won. In another split decision, the

appeals court threw out Alonzo King’s conviction.

Five of the seven judges held that Maryland’s DNA Collection

Act was unconstitutional “because King’s expectation of privacy is greater

than the State’s purported interest in using King’s DNA to identify him

for purposes of his 10 April 2009 arrest on the assault charges.” King’s

DNA, they wrote, was “obtained illegally.”

Maryland attorney general Douglas Gansler appealed the ruling

to the US Supreme Court. The court agreed to hear the case. Chief Justice

John Roberts issued a stay, which put King’s case on hold and kept him in

jail until the high court ruled.

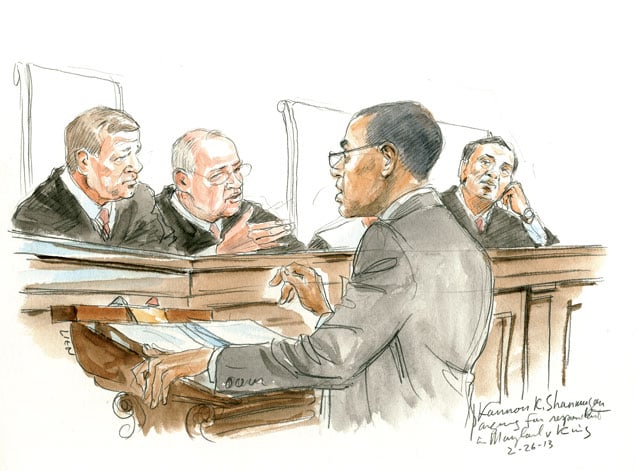

The two sides prepared to argue the case on February 26,

2013.

• • •

Kannon Shanmugam was in his office at Williams & Connolly

last summer when he received a call from Adrienne Coleman, Alonzo King’s

aunt.

“She called out of the blue,” he says. “She wanted to know if I

would get involved.”

Shanmugam, 40, sits atop Williams & Connolly’s appellate

practice. He has argued 13 cases before the Supreme Court, tying the

number of appearances by the legendary Edward Bennett Williams, for whom

the firm is named. A graduate of Harvard Law, Shanmugam clerked for

Supreme Court justice Antonin Scalia.

Mercer and his colleagues with Maryland’s public-defender

office had a working relationship with Shanmugam and had alerted him to

the King case. They sensed that it had the potential to test

constitutional questions about DNA collection, and they believed Shanmugam

might be the best advocate for their cause.

King fit the profile of a Williams & Connolly pro bono

client: He was indigent, and the case had far-reaching implications. But

why argue against using DNA to solve a case like the rape of Mary

Johnson?

“At first, many people have that impression,” Shanmugam says.

“I’m not arguing that the earth is flat. DNA is obviously an important

tool. If you want to obtain it through a search, you must prove probable

cause or individualized suspicion.”

Shanmugam would be arguing against Maryland and the federal

government, which also has laws that allow police to take DNA when a

suspect is arrested.

Once the government has someone’s DNA, Shanmugam argues in his

briefs, Big Brother has possession of that person’s genetic blueprint.

Allowing the government to collect and keep DNA raises privacy concerns,

he writes, because it contains “information that can be used to make

predictions about a host of physical and behavioral characteristics,

ranging from the subject’s age, ethnicity, and intelligence to the

subject’s propensity for violence and addiction.”

Shanmugam acknowledges that laws prohibit unauthorized

disclosures of DNA, but he points out that Maryland’s law allows sharing

DNA for “research” purposes. And he notes that state attorney general

Gansler “embraced” the notion that the government would eventually have

everyone’s DNA, because Gansler testified before the legislature that

someday “everybody’s DNA” would be in some sort of a database, “like with

our Social Security numbers.”

Shanmugam wrote in his brief: “Some Fourth Amendment incursions

may come dressed in sheep’s clothing. This wolf comes as a

wolf.”

While Shanmugam prepared his case on the ninth floor of

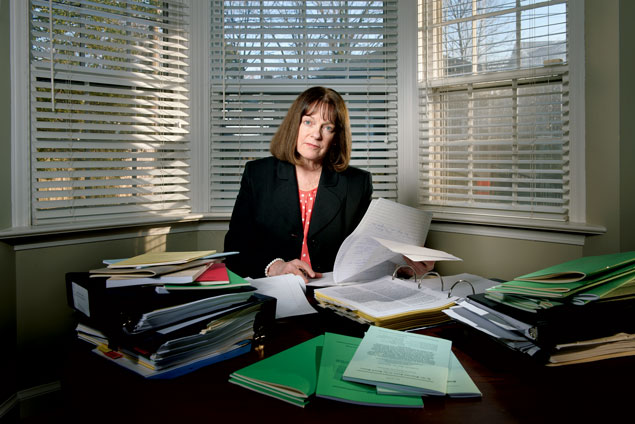

Williams & Connolly in downtown DC, Katherine Winfree hunkered down in

her home in Bethesda. (“More peaceful here,” she says.) Winfree would

argue for Maryland. It would be her first argument before the Supreme

Court.

Kay Winfree, 61, works most of the time in Baltimore as chief

deputy attorney general under Doug Gansler. Early in her prosecutorial

career, she had served as an assistant US Attorney in DC, where she was

Gansler’s boss. She went with him to Montgomery County to become his

deputy when he was state’s attorney. For the past six years, she has

worked by his side in the Baltimore office.

Gansler had already argued a case before the Supreme Court. “He

figured I should get a chance, too,” she says.

In the weeks leading up to February 26, Winfree prepared to

argue that an arrestee had a diminished expectation of

privacy.

“Taking DNA is no different than a fingerprint or a

photograph,” she says. “You can be ordered to pee, for example. Your

privacy is gone as a result of your arrest.”

“What scares people about DNA,” she says, “is that a person’s

entire genome sequence can become known. Our lab doesn’t have the

capability or the software to get that information. It’s a fantastic

concern.” State and federal criminal DNA databases don’t contain entire

genomes. Instead they use just 13 markers that can identify an individual

but are believed to hold little personal information.

“The technology advanced rapidly,” Winfree says, “but these

advances take time to get through the courts. The utility of DNA has

grown. It helps to exonerate, to identify human remains, to help figure if

an arrestee is a flight risk.

“No one has seriously challenged DNA collection laws. This is

the first time.”

Winfree says she has two goals: “To win and not to embarrass

myself. If I win and embarrass myself, I will get over it.”

• • •

At 11:10 on the morning of February 26, Chief Justice John

Roberts looked down on a packed Supreme Court gallery and said: “Ms.

Winfree?”

Winfree stepped to the lectern and said that DNA samples from

arrestees had been essential in 75 prosecutions and 42 convictions

“including that of respondent King.”

Justice Antonin Scalia cut her off. “Well,” he said, “that’s

really good. I’ll bet you if you conducted a lot of unreasonable searches

and seizures, you’d get more convictions, too.”

Laughter came from the audience.

“That proves absolutely nothing,” Scalia said.

Roberts asked if under her theory cops could take DNA from

“anybody pulled over for a traffic violation.”

Not in Maryland, she said.

Justices Elena Kagan and Sonia Sotomayor hammered

Winfree.

Kagan: “Assume you’ve been arrested for something—the state

doesn’t have the right to go search your house for evidence of unrelated

crimes. Isn’t that correct?”

Winfree agreed but added: “There’s a very real distinction

between the police generally rummaging in your home to look for evidence

that might relate to your personal papers and your thoughts. It’s a very

real difference there than swabbing the inside of an arrestee’s cheek to

determine what that person’s CODIS DNA profile is.”

Sotomayor asked: “How far do we let the state go each time it

has some form of custody over you, in schools, in workplaces, wherever

else the state has control over your person?”

Winfree said those were “different situations” and added:

“We’re not suggesting that—that the police could swab a student for a DNA

sample. We’re talking about a special class of people who, by their

conduct, have been arrested based on probable cause.”

Winfree passed the lectern to Michael Dreeben, deputy solicitor

general, who was arguing for the federal government. He asserted that

arrestees have lost certain privacy rights and can be strip-searched, for

example.

Justice Samuel Alito, who seemed to agree with the government,

called DNA testing the 21st-century fingerprint. The FBI has a database of

fingerprints, for example, that holds more than 70 million

subjects.

When it was Kannon Shanmugam’s turn, he attempted to

distinguish between the two: Fingerprinting is “not a search” because

there’s no intrusion into a person’s body.

Another difference, he said, is that “the primary purpose of

fingerprinting is to identify an individual who is being taken into the

criminal-justice system.” Fingerprints are also used for crime-solving,

Shanmugam argued, but that’s not the main reason they’re taken, whereas

the only purpose of DNA collection is to link a person to a

crime.

But Dreeben and Winfree argued that DNA could soon be the

better tool for identification. In the not-so-distant future, as

technology speeds up the time it takes to process DNA—from months to days

to hours—genetic profiles could replace fingerprinting for

identification.

Roberts asked: “How can I base a decision today on what you

tell me is going to happen in two years?”

Justice Anthony Kennedy questioned Shanmugam’s assertion that

arrestees had many privacy rights. Roberts wondered whether DNA could be

protected at all.

“If you’re in the interview room or something,” the chief

justice said, “you take a drink of water, you leave, you’re done. I mean,

they can examine the DNA from that drink of water.”

Kennedy asked Shanmugam if the government, once it has arrested

someone, has “a legitimate interest in knowing if that person has

committed other crimes.”

“They have that interest,” Shanmugam said, “but if they want to

investigate other crimes, they have to do what they would have to do to an

ordinary citizen. They have to have a warrant or some level of

individualized suspicion.”

Kennedy seemed unconvinced.

Shanmugam’s only reliable defender was Justice Scalia, who

butted into Winfree’s closing argument and said of using DNA: “The purpose

now is—the purpose you began your presentation with, to catch the bad

guys, which is a good thing. But, you know, the Fourth Amendment sometimes

stands in the way.”

• • •

Mary Johnson didn’t attend the Supreme Court argument. Steve

Mercer sat by Shanmugam’s side. Liz Ireland was not in the courtroom; she

had left the prosecutor’s office and now works for the Life Crisis Center,

a domestic-violence shelter in Salisbury.

Alonzo King Jr. remained in jail as the nine justices

considered his fate. They’ll decide by June. Lawyers and Supreme Court

observers say the ruling could go either way.

“If that law goes down,” says Liz Ireland, “a lot of rapists

and murderers will be back on the street.”

Alonzo King could be one of them. If the Supreme Court affirms

the Maryland Court of Appeals ruling that King’s constitutional rights

were violated, his case will go back to Wicomico County. Assistant state’s

attorney Joel Todd will try the case.

“I will have to retry the case without the DNA,” he says.

Because DNA is the only evidence that ties him to the rape of Mary

Johnson, he could go free.

“That,” Johnson told Ireland, “would make my life a living

hell.”

National editor Harry Jaffe’s “Predator in the Ranks,” about

a Marine convicted of rape and accused of murder, appeared in

September.

This article appears in the May 2013 issue of The Washingtonian.