James Dean had it. So did Muhammad Ali. John Travolta had it and lost it. Defining “cool” is a task that has challenged teenagers and lexicographers alike for generations. Tulane University historian Joel Dinerstein and then-National Portrait Gallery curator Frank H. Goodyear III had been casually discussing an exhibition about the history of cool for several years, but it wasn’t till a politician named Barack Obama entered the picture that they wrote a proposal.

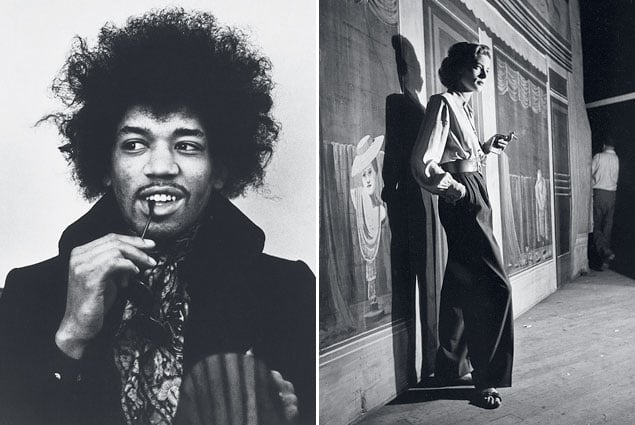

“There was a lot of conversation about Obama’s cool during the lead-up to the 2008 election,” Goodyear says. “We thought what we should do was excavate the origins and evolution of that particular persona.” The result is “American Cool,” an exhibit of photographs—opening February 7 at the Portrait Gallery—that looks at 100 people who have embodied cool at one point or another, from Greta Garbo and James Cagney to Patti Smith and Jay-Z.

The show’s four sections explore the roots of cool, its birth in the ’40s and ’50s, its links to the counterculture in the ’60s and ’70s, and cool from the ’80s to today. Dinerstein and Goodyear had four criteria: Subjects had to have made an obvious contribution in their field, have had some kind of transgressive or rebellious side, and have had a lasting impact beyond their generation; most important, there had to be a good picture of them available.

Some were obvious choices, others more contentious. “Frank and I worked incredibly harmoniously, but there were disagreements,” Dinerstein says. “We had a huge argument over John Travolta.” Says Goodyear: “While the movies he made in the mid- to late ’70s were resonant at that time, what I knew Travolta from was some fairly lame movies and his connection with Scientology.” So they took an academic approach and polled students between ages 18 and 21, who overwhelmingly agreed Travolta should be included. The same with rapper Missy Elliott, to whom students gave preference over Queen Latifah.

Besides exploring cool, the show examines how the rise of photography ran parallel to the word’s entry into the public consciousness. “Photography was the dominant visual medium during the midcentury when these figures were making their mark,” Goodyear says. “It was through photography that the public came to know them.” Among the highlights: images by Diane Arbus, Annie Leibovitz, Richard Avedon, and Henri Cartier-Bresson.

Although Goodyear and Dinerstein agree Washington isn’t renowned as the center of cool, they think it’s a fitting location for the show. “Cool is central to the American self-concept,” Dinerstein says. “What better place than the nation’s capital and the Smithsonian?” But despite the fact that Obama’s election served as inspiration, the President didn’t make the cut. “When he was elected, the public perception of him—and to some degree his larger persona—changed,” Goodyear says. “As President, it’s impossible to be antiestablishment.”

Through September 7; npg.si.edu.

This article appears in the February 2014 issue of Washingtonian.