It’s hot and bright in the glass-enclosed gun turret where Staff Sergeant Pearce sits alone atop a dusty Humvee rattling through the Iraqi desert.

His hands on a machine gun, he scans the ground for bombs and the roadside for snipers, while the driver swerves around deep craters blasted into the road from earlier attacks. As Pearce’s five-vehicle convoy crawls along, he tries to push aside his fear about what could happen, about the explosions and gunfights he’s witnessed all these months at war. He sounds the all-clear over the radio: “Looks like those sons of bitches didn’t get us this time.”

A moment later, Pearce hears a blast and sees a smoky fog while the Humvee flies into the air and slams back down against the road. A piece of shrapnel pierces the turret and his helmet, lodging in his skull, and he’s thrown from the truck onto the ground, surrounded by glass, dust, and blood. A quiet comes over him. Everything goes dark.

Then Logan Pearce wakes up. Heart racing, he’s sweaty and nauseated and trembling with fear at the memories of war, memories that are seven years old and that he still can’t shake. He’s like so many soldiers who return from combat with rattled brains—angry, anxious, and depressed. So depressed that, also like many soldiers, he has considered ending his life.

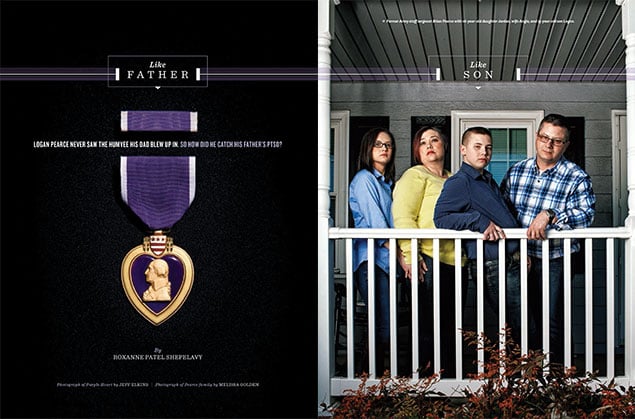

Except for one thing: Logan is 15 years old. He was never actually in Iraq, never fought a war or got blown up in the desert. His flashbacks are not his. They belong to his father, former US Army staff sergeant Brian Pearce, whose Humvee rode over an improvised explosive device (IED) while escorting a water truck to a medical clinic in Mushada, who almost died from shrapnel in his brain, and who returned from Iraq with physical and psychological injuries from which he struggles to recover.

Logan was just seven when his father came home, yet he’s become an unwitting victim of this war’s most lingering injury: posttraumatic stress disorder.

★ ★ ★

The Pearces live in Mechanicsville, Virginia, not far from the VA Polytrauma Rehabilitation Center in Richmond, where Brian, 43, expects he’ll need to go for treatment and therapy the rest of his life. Brian is—they are—no longer in the Army. But the Pearces don’t exactly live like civilians, either. Inside, the house is spare and dim, with nearly empty walls and the curtains always drawn to cut down on the shadows that make it hard for Brian to see. Except for the emblems—a three-story flagpole outside, a bald-eagle sculpture in the fireplace, a framed poster of a soldier in the dining room—it’s as though they haven’t fully settled in yet.

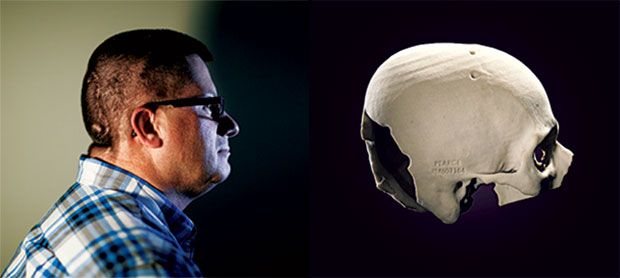

Seven and a half years after a shard of shrapnel from the IED severed his optic nerve, Brian still wears his injury. His military buzzcut reveals the tube that snakes under his skin from the front of his head to his neck, then all the way down into his abdomen. Doctors inserted it to drain excess spinal fluid from his brain and to prevent debilitating headaches. On the back of his head, a mosaic of scars shows where Brian’s surgeons removed a portion of his skull to relieve bleeding in his brain. He’s legally blind from the damage to his optic nerve and has lost his peripheral vision. He looks at the world as though through straws.

The bigger problem is what’s inside Brian’s head: The shaking of his brain during the explosion seems to have literally rattled his psyche, making him extra jumpy, paranoid, forgetful, prone to temper tantrums and childlike illogic. (Only in the last year has he conceded that hunting was a bad idea.)

Brian has a traumatic brain injury (TBI) and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and everything that comes with these invisible wounds: flashbacks, nightmares, depression, emotional distance, helplessness. He careens like a pinball in his own mind. The rest of the Pearces careen around his moods, around him.

“We’re still getting used to our new normal,” says Brian’s wife, Angie, the family’s narrator, in a booming voice that hides nothing. With a bottle-red pixie cut and a tattoo across her lower back, she looks younger and more carefree than what she really is: a 37-year-old woman who has almost single-handedly held her crumbling family together for years. “This is our life now. We’ve had to learn to deal with where Brian is, where we all are, and move forward. That’s just . . . hard.”

Angie and Brian married two weeks after they met in 1996, when she was 19 and he was 26. Two years later, they had a daughter, Jordan; a year after that, Logan. Brian spent eight years in the Army, deploying to Somalia, Bosnia, and Honduras, before his contract ended in 2000. He took on three police jobs simultaneously but couldn’t support his family on all of them, so in 2004 he reenlisted. Shortly after that, the Pearces moved from their native Ohio to Alaska, near Fort Wainwright, where Brian was stationed. “We knew the risks,” Angie says. “We planned for this to be Brian’s career.”

The call Angie had dreaded since Brian was sent to Iraq in 2005 came early in the morning of October 20, 2006, while she was still in bed, with Logan next to her. A sensitive boy with intense moods, Logan was his mother’s shadow—he liked her near him always. Angie knew it was something bad, even as the Army officer on the phone tried to assure her everything would be fine. In the course of two phone calls, she learned only that Brian had survived brain surgery and was to be flown to Walter Reed Army Medical Center.

Angie tried to remain calm for the kids. But seven-year-old Logan heard the panic in her voice and felt a flood of anxiety drench him. He buried his face in his pillow, stiffened his entire body, and waited for the feeling to pass. It stayed. A few days later, Angie left the kids in Alaska with close friends to go meet Brian in DC. Logan felt like he was the one who’d rolled over a bomb. “I didn’t know if my dad was dead or when my mom was coming back,” he recalls. “All I knew was that they were both gone. And everything just stopped for me.”

Angie never returned to Alaska. Instead, the Army packed up her house seven weeks later and flew the kids east. They reunited with Brian in his room at the VA Hospital in Richmond, where he had been moved from Walter Reed.

Logan didn’t know what to expect. By now, he knew his dad had survived—they had spoken on the phone, though only briefly. His mom had been vague about the details: After nearly dying on the street, and again on the plane, Brian had spent six weeks in a coma. He woke up gradually, with no memory of anything after rolling over the IED.

Now he was out of the intensive-care unit and sitting up in bed, wearing a skullcap with wires attached to his head, to test for seizures. “They’re going to turn me into a rabbit,” he joked to the kids. Logan was relieved: Their dad was alive, being goofy. They were together.

But as would soon become clear, Brian wasn’t really present. He was lost somewhere in the Iraqi desert. One minute, he felt the blast under him; the next, he was in an American hospital with Angie by his side. He never got to say goodbye to his buddies or have a heroic homecoming or ease out of the supercharged tensions of war into the everyday tensions of home.

★ ★ ★

Shortly after moving into their new house in Mechanicsville, Jordan brought home a dark-haired ten-year-old girl she had befriended. Brian took one look at her and flipped out. He stormed out of the room, yelling, and ordered Jordan to send her home. “Basically, he was a total ass to this little girl,” Angie says.

This went on for two years, until one night Brian woke up from a dream with a realization: The girl reminded him of an Iraqi woman he thought he recalled killing in a Baghdad market before she could detonate a bomb strapped to her chest.

“How the hell are we supposed to tell our daughter that she can’t have a friend over because it sends you back to Iraq?” Angie asked.

(Brian’s direct superior, Command Sergeant Major James Fraijo, says the incident with the Iraqi woman never happened, though they did encounter a suspicious woman at a known spot for attacks. Brian seems to be misremembering several events, a common effect of TBI.)

One day around this time, the Pearces were at Walmart when Brian caught a whiff of someone’s strong perfume. Instantly, he was back at a Tajik bazaar filled with the sweet smell of scented oils. He started pacing, muttering under his breath. His eyes glazed over, like “his soul was removed,” Angie says.

“We just need to go, now!” Brian exploded.

Angie tried to calm him down, but he got angrier and louder. “F— off!” he shouted, oblivious to customers’ stares as he pushed his family out of the store. He was agitated on the way home, and it took a few days before he could explain to Angie what had transpired in his mind.

“The reality of being in the Walmart in Mechanicsville, Virginia, was gone,” he says. “I was back in Iraq, at a market where I’d been many times. All I knew was that I had to get to safety.”

★ ★ ★

Brian struggled to understand his own behavior. He refused to admit that his PTSD was a problem. Instead, he blamed Angie or the kids for his constant anger. He couldn’t remember simple things, such as why he’d walked into a room. He couldn’t work or help around the house because his eyes were bad. He got confused and blew up when things didn’t go his way. He felt out of place in his own family, who had done without him for so long.

“I was angry at the world, for everything,” he says. “But for the longest time, I wanted to say that nothing was wrong with me. I was fine—it’s everybody else who was having an issue.”

At night, and sometimes even during the day, Brian had flashbacks of the IED that had ended his war: the ride down the pocked Iraqi road; the sudden bam! that sent shrapnel through the glass turret, under his helmet, and up through the base of his skull. He pictured himself waiting in a pool of his blood for a helicopter to take him to the hospital in Baghdad.

In his nightmares, Brian searched helplessly for the wire that triggered the bomb, as if finding it in his dream would change anything. Instead, he woke up feeling even more hopeless than before.

Why am I even here? he wondered. Wouldn’t it have been better for everyone if I had died over there?

Every few months, Brian became convinced that nothing would ever get better, and he thought about killing himself, just to put an end to a feeling he can articulate only in simple terms: “This sucks.”

He didn’t say anything to anyone. But Angie could sense his despair. She made sure there was no ammunition for Logan’s BB gun, the only gun in the house, and hoped things would get better eventually. Instead, they got worse, she says: “Those first couple years, we were so focused on getting Brian physically well that no one really noticed we were all falling apart.”

★ ★ ★

Logan has heard bits and pieces of Brian’s story over the years—mostly snippets of conversation between adults before leaving the room, as he does even now when the topic comes up. He has never sat down with Brian to discuss the details or studied the photographs his dad keeps to remind him of Iraq. Not even the one of the Humvee shot through with shrapnel in 37 places.

Somehow, though, Logan has managed to piece together the IED attack almost perfectly. “Logan has a very active imagination,” Brian says. “I think he just filled in the gaps of what he heard and pretty much got it right.”

Even before Brian’s injury, Logan was a delicate child, high-strung and scared—of water and bugs and darkness. He was diagnosed with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) when he was five and was put on medication while in kindergarten. More recently, he was found to have high-functioning Asperger’s syndrome. Getting through a typical day in second grade was already a fraught experience for Logan in October of 2006, when his father got hurt. Then his mother left him in Alaska to meet Brian and didn’t come back for him. Logan fell to pieces.

Reunited with his parents in Virginia in December of that year, the boy worried constantly that they’d abandon him again. He rarely left his mother’s side, following her everywhere when they were out, even to the ladies’ room. He slept in his parents’ room and wet the bed until he was 13. School was torture. With his dad in and out of the hospital for years, Logan agonized over what he’d find upon coming home: Would his dad be alive? Would his mom still be there?

Three years after the explosion, Logan started complaining of near constant headaches and stomachaches—some real, some just an excuse to take a break in the bathroom or see the school nurse, who let him call home. “Are you okay?” he’d ask his mom. “What are you doing? Is Dad okay?”

Even at home, Logan’s anxiety ate away at him. He started throwing up spontaneously; his doctor diagnosed an H. pylori infection, a cause of stomach ulcers. He was 11.

Over time, Jordan and Logan learned to navigate their father’s flashbacks. When a book fell or a car backfired, they rushed to assure him everything was fine. They held onto his arm in crowds so they could see what he saw and remind him that they were safe, that he was safe.

Jordan was able to separate herself from Brian, to compartmentalize what was happening at home from where she was, at school or with friends. Logan, though, took the change in Brian personally. He wanted to go fishing, hunting, and camping with his dad, as Brian had always promised. He wanted to bond with his distant father, to be like him—he buzzcut his hair and continued to wear the dog tags Brian had given him when he left for Iraq.

Brian’s fears fed Logan’s fears, so Logan started scanning a room for assailants and exits, even when Brian wasn’t around. He got clammy and out of breath in crowds and started jumping at loud sounds—everything was a threat. One Christmas, Brian offered to take the kids to the mall, in a taxi because he can’t drive. Logan refused. “I’m not going in a taxi,” he said. “You don’t know if that driver is going to be an ax murderer or something.”

★ ★ ★

Like his father, Logan was also angry. He fought with kids at school over what he took as insults, often about the military. From the time he was little, he’d wanted to join the Army when he grew up, like his dad. After Brian got wounded, Logan said he wanted to be a soldier so he could go to Iraq and find the family of the man who had triggered the IED.

“I’ll hunt him down and I’ll murder them all,” Logan said. “I don’t care what happens to me—they deserve it.”

Mostly, though, Logan’s anger was directed at his father. “We fought about everything, all the time,” Brian says. “It could be about his fear of bugs or school or even the weather. Nothing I said was okay with him—and vice versa.”

One evening a couple of years after the attack, Brian and Logan started arguing about where to go out for dinner. Logan rolled his eyes at his father, said something snide. Suddenly, Brian’s voice got deeper and louder, like a drill sergeant’s. He marched over to Logan, his finger jabbing the air. When Logan backed away, Brian started chasing him, “like I was a thug running down the street,” Logan says. Brian pinned him down on the ground by the back door of the house. His eyes were empty, his face blank. Terrified, Logan froze and started crying, unsure what his father might do next.

“Brian, you need to stop!” Angie shouted.

Still Brian held onto Logan, his eyes blank and unseeing.

Angie shouted again and again. “Let! Him! Go!”

After a few moments, Brian snapped out of it, leaped back, and started crying himself, shocked by what he’d done. It was the closest he’d ever gotten to becoming violent with his family, something they know makes them luckier than some. (“I have heard terrible stories of men who come home and try to kill their wives because of their PTSD,” Angie says.) But to Logan, it confirmed what he had feared: His father was home, but completely lost to him.

By the spring of 2010, when Logan was 11, he was so distracted at school that he asked the psychiatrist treating his ADHD to change his medication. A few weeks later, his psychiatrist also prescribed him Geodon, a medicine for bipolar disorder, to combat his mood swings. The new regimen only made Logan feel worse. His mind, ever racing, ricocheted from anger to sadness to giddiness. One minute, he looked at his father struggling and felt sympathy for him; the next, he flew into a rage because Brian had said something he didn’t like. For weeks, Logan and Brian battled, with Angie between them, trying to calm everyone down.

But Logan couldn’t calm his mind, and his frustration soon turned to anguish. One evening that spring during a family discussion around the dining-room table, Brian snapped at Angie. Logan rushed to her defense. “Don’t talk to my mom that way!” he shouted. As Brian turned to face him, Logan jumped up from his chair, swiveled around, and started bashing his own head against the wall.

Bang!

“I want this to end!”

Bang!

“I wish I had never been born!”

Bang!

“I can’t deal with this anymore!”

Jordan put her hand against the wall, to cushion Logan’s head, while Brian watched his son in confusion. What did I say? he wondered.

Angie grabbed Logan in a bear hug and held him until he calmed down. She couldn’t comprehend what her child was saying. How could he mean he didn’t want to live? What had they done to him? Spent, Logan finally acknowledged what he’d been thinking about for weeks.

“I wish I was dead,” he said. “Maybe if I bang my head hard enough, I’ll get hurt like Dad. Then I’ll understand what he’s going through and he’ll understand me.”

★ ★ ★

Logan spent 12 days over the next three months in two psychiatric facilities, where he admitted he had done more than just think about dying—he had made plans. He’d considered cutting himself with his knife collection or overdosing on his dad’s drugs or truly banging his head hard enough to kill himself. “I didn’t think it would be that big a deal if I died,” Logan recalls. “I was so done, I didn’t really care what happened.”

His doctors revised his medications again, taking him off the bipolar drug and instead prescribing Zoloft for anxiety. Logan also started meeting regularly with Anne Allen, a therapist whose ex-husband was a Vietnam vet with PTSD. At her first meeting with the Pearces, in late June of 2010, Allen realized they were all suffering in their own ways.

“Logan was suicidal, Angie was overwhelmed and depressed and anxious, Jordan was drifting along,” Allen says. “The whole family mirrored Brian’s moods, wherever he was at that moment. They could not separate themselves at all.”

Allen suspected that all three Pearces had secondary PTSD, at the time an unofficial ailment that therapists and researchers had observed in families of trauma survivors since the Holocaust. The condition, in which trauma passes from a close relative or friend to another, was officially recognized by the scientific community in 2013, when the American Psychiatric Association expanded the definition of PTSD to include people like the Pearces.

The shift came partly as a result of the decade-long wars. Some 2 million American children have had a parent serve in Iraq or Afghanistan. For most of those kids, a parent’s return home has signaled a return to normal life. But thousands have found themselves welcoming back moms and dads who have been irreparably changed by combat. Since 2002, more than 286,000 veterans who served in Iraq and Afghanistan have been diagnosed with PTSD, according to the Department of Veterans Affairs. Since 2007, more than 63,000 have been found to have a traumatic brain injury. An estimated 5 percent of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans—of whom Brian Pearce is one—are suffering because of both conditions, as well as depression.

These psychological problems can have a profound effect on their children, according to Stephen Cozza, a psychiatrist at the Uniformed Services University, a military medical school. “If a child is exposed to PTSD in the form of domestic violence or their dad’s flashbacks or some other scary behavior, they could become traumatized themselves,” says Cozza, who’s studying the effects of combat injury on children and families. “Over time, that becomes embedded and shapes the way children feel about themselves and their families. That can carry through their whole lives.”

Researchers haven’t pinpointed exactly how PTSD transfers from parent to child. Some of it may be physiological. Neuroscientists have noted that continual stress in childhood can dramatically alter the brain’s development, in particular the amygdala and hippocampus, the areas that control memory and emotional reactions. Normal stress can be good: Fear stimulates the brain to react to danger and teaches children to weather negative events. But heightened stress that’s constant does the opposite: The sense of continual danger may make children prone to aggression, misbehavior, and future health and substance-abuse issues—all symptoms of PTSD.

“Being exposed to constant stressors early in life changes your threshold for reacting to something,” says Peter Gianaros, a psychology professor and brain researcher at the University of Pittsburgh. “The brain learns what kind of environment it’s exposed to and what it is likely to encounter in the future. It puts you constantly on edge.” Researchers have observed this phenomenon among civilian children who live in poverty, dangerous neighborhoods, or abusive homes. Some say this could also be the case with children who live with PTSD-afflicted veterans.

“Logan kicked into survival mode when his mom left and never was able to move past it,” says Anne Allen, Logan’s therapist. She suspects that biology could account for some of his issues. “A child’s development takes energy, support, and stimulation. When they’re focused on survival, they can’t grow in other ways—emotionally, intellectually, or socially.”

★ ★ ★

Clinicians who counsel traumatized families say the experience of PTSD may be less about biology and more about learned behavior. The Pearces, for example, became so used to jumping at loud sounds in order to soothe Brian that now they do it even when he’s not around. This isn’t so different from kids picking up their parents’ prejudices, accents, or superstitions.

“Kids rely on their parents for social referencing on how to react to something,” says Jamie Howard, a psychologist who has worked with veterans and their families at the Child Mind Institute, a brain-research-and-treatment center in New York. “If a parent feels chronically unsafe, a kid can pick up on that. For instance, they can also start to think that it’s not safe to sit with their back to the door.”

For active-duty servicemembers and their families, the Defense Department offers a spectrum of health services, including family and individual therapy to deal with PTSD. Once they’re discharged, though, the VA is authorized to treat only the veteran. Families must find therapists in the private sector who are covered by Tricare, the military health plan offered to most veterans.

That’s not so simple. “It’s hard for a lot of military families to open up with therapists who have no military background,” Allen says. “There’s a cultural difference. They don’t always understand that when one member of a family enlists, the whole family enlists, trains, and deploys. Everyone has to be retrained as a civilian, even when they’ve never been to war.”

The good news is that clinicians have found that families such as the Pearces, who recognize the PTSD and get help, can recover. Children who learn how to cope with their parents’ trauma can even become more adept at dealing with hardship throughout their lives.

“Often you have kids who develop a tremendous capacity for compassion and empathy that will help them in the long run,” says Barbara Van Dahlen, a child psychologist who founded Give an Hour, a nonprofit that offers free therapy to veterans and their families. “The most important message I always give to families is don’t give up. There is a way out of this.”

★ ★ ★

Logan’s suicidal breakdown was not the end of troubles for the Pearces. After witnessing his son’s agony, Brian said he was ready to move on from Iraq, to work on healing his brain and his family. But he wasn’t. He couldn’t come to terms with what he had done to Logan, what his son had said: that he wanted to hurt himself so his dad would understand him.

Brian gradually became even more distant from his family, lying to his VA therapist week after week and refusing to admit that anything was wrong. “I couldn’t see it,” he says. “Or I wasn’t ready to. I know everyone was walking on eggshells around me, but at the time I just didn’t really care.”

In 2011, Brian became as physically well as he’ll probably ever be. Logan kept up his therapy with Allen, going to see her every two weeks, and adjusted to his new medications, which seemed to calm him down and help him focus. But at the same time, Angie and Jordan started to crumble.

For years, Jordan had been like a surrogate mother to her brother. Now she started to focus on herself and discovered she was depressed. She struggled to sleep at night. During the day, she snapped at Brian and burst into tears over the slightest frustration.

Angie also started therapy with Allen, finally tending to her own emotions. She, too, was depressed and grieving the loss of her husband, who in many ways had died in Iraq. She was also diagnosed with fibromyalgia, a painful disorder that many clinicians think may be related to stress. “It’s like we fell apart when we no longer had to worry so much about Brian,” Angie says.

By the spring of 2012, Angie was so exhausted and frustrated that she couldn’t stand to be in the same room as her husband. “It felt like I had lost everything about Brian that I loved,” she says. “I no longer even really liked him.” After all the years of struggling to make Brian better, Angie was ready to give up.

★ ★ ★

Then one day for no particular reason, Brian woke up and decided to make a change. He asked Angie to find him a new therapist—one who would force him to be honest. “I don’t want to live like this,” he said. “But I do want to live.”

Finally, Brian admitted what everyone had known: His PTSD was controlling them all, and only he could free them of it. “My world is Angie and the kids,” he says. “I finally decided to act like it.”

In the last two years, Angie has learned to love Brian again, digging deep inside the man who returned from Iraq to find the parts that she loved before he left. Brian has learned to appreciate Angie, who “held us all together,” he says.

And he has started to build a relationship with his children, in simple ways: engaging them in conversation, offering them advice, trying to understand who they are. Although he’s been home from Iraq for seven years, he has really been a father to them for only two—a small fraction of his teenage children’s lives.

“They got so used to doing without me that they don’t know how to talk to me,” he says. “We’re still working on that.”

One of the Pearces’ prized possessions is a plaster mold of Brian’s skull, with a piece missing near the back, that doctors made when he was in the hospital. Angie asked for it when Brian left the VA. For visitors, she pulls it out of a plastic Ziploc bag and holds it gingerly in her hand, as though to underscore a contrast: It is small, hollow, and delicate, unlike the Pearces themselves, who have proven themselves strong and resilient and who will tell you, now—37 shards of shrapnel and 7½ years after an IED nearly tore their family apart—that they aren’t mad Brian went to war.

“He knew the risks of the job, and he was happy to do it,” Logan says. “That’s nothing to be angry about.”

Now 15, Logan has started to lighten up a bit. He still bears the legacy of his father’s illness in his fears and nightmares and hypervigilance. But he no longer harbors fantasies of killing his father’s attacker; he no longer wants to hurt himself.

“If I had died, I’d not be here to see my dad getting better,” Logan says. “He hasn’t just quit and shut down. He’s still trying to fight through. I’m really proud of him.”

Logan knows that his history means he’ll probably never follow his father into the military. But he is actually thinking about his future, a sign that he has finally moved past his years-long trauma. Like so many children of veterans, he wants to dedicate his life to public service, as a police officer or firefighter.

He doesn’t yet have the father/son relationship he wants. There’s no bonding with his dad over a campsite, a rifle, or a fishing line. Even so, it does feel like he finally has his father home.

“Things still happen,” Logan says. “But they’re more like normal family moments. We’ve gotten so used to the way things are, now it would be harder to go back.”

Roxanne Patel Shepelavy, a freelance writer in Philadelphia, can be reached at roxanne@shepelavy.com. This article appears in the June 2014 issue of Washingtonian.