Fifty years ago, on August 17, 1964, the final piece of the Capital Beltway was opened to traffic, forever changing the Washington region in ways that went far beyond just transportation. Portions of the highway had been opening since 1957, but in completing the ring, the moment ushered in an era that would see the suburbs blossom and the once-disparate region finally unite.

“In my view, the greatest legacy of the Beltway has been its unification of metropolitan Washington as a distinct region,” says Jeremy Korr, a dean at Brandman University in California who wrote his dissertation on the Beltway while at the University of Maryland. “There wasn’t that much that made the area a cohesive unit, largely because it was so time-consuming and mentally draining to get from Maryland to the District to Virginia and back.”

But the highway also decentralized the region, hastening a hollowing-out of downtown DC that is only now starting to reverse. It also would become the bane of many commuters’ existence, as more and more traffic poured into the road in ways the engineers hadn’t expected or designed for.

Here, in facts and figures about its opening and early years, is a hidden history of the Capital Beltway.

A Not-So-Happy Hour?

Drivers were ecstatic during the Beltway’s first few months of operation. Destinations that could once only be reached via narrow, slow roads were now accessible by this massive and quick-moving highway. Newspapers ran letters from commuters praising the new road. Korr says there was even a possibly apocryphal story from this time that said local bars were losing business because workers could no longer tell their wives they’d been stuck in traffic when they were really grabbing a drink. But the Beltway’s problems soon became apparent.

5 Minutes

The time it took for the first traffic jam to form on the Beltway after it opened. A crowd of thousands had gathered for the inaugural ceremony, then dashed to their cars as soon as the ribbon was cut. This caused a two-mile-long jam at the New Hampshire Avenue interchange in Hillandale that took 20 minutes to clear—an ominous sign of the road’s future.

“I’ll never get out of here . . . I’m tempted to walk home and come back tonight for my car.”

—A quote from a “pipe-smoking driver” trapped in the Beltway’s first bumper-to-bumper traffic, appearing in the Washington Post’s coverage of the opening.

55,000

The number of vehicles per day Maryland traffic officials expected to use that state’s portion of the Beltway.

1 Year

Time it took to top that estimate. Further increases in traffic rose much sharper than engineers predicted. Today the busiest sections of the Beltway can average 200,000 to 225,000 vehicles a day.

15 Months

Time it took after the Beltway’s opening for AAA to convene a forum titled “Golden Ring or Vicious Circle?,” to debate whether the highway lived up to its promise or was already doomed to failure.

13

Number of fatal crashes on the Maryland portion of the Beltway during its first full year of operation. In 2013, there were four.

Unintended Consequences

In allowing vehicles to traverse suburb to suburb, the Beltway changed the economic center of the region. As in many other cities during the era, businesses and residents left downtown DC in droves, relocating to the suburbs. From 1982 to 1997, the region saw a 12 percent drop in density, and 47 percent of jobs were at least ten miles away from the city’s core by 2010, according to the Brookings Institution.

Robert Puentes, senior fellow at Brookings’ Metropolitan Policy Program, says the road hastened this kind of low-density, single-use sprawl. “There’s no doubt that the development of the exurban areas was facilitated by the Capital Beltway,” he says. “If the highway network isn’t there, you’re not going to have that kind of growth.”

Korr says that this diffusion put additional stress on the already overcrowded Beltway, which was designed for a more traditional suburb-to-downtown commute.

779%

The increase in the price of land in Fairfax County near the Beltway, from $1,900 an acre in 1951 to $16,700 in 1964.

450

The number of apartment units within two miles of Fairfax County’s portion of the Beltway when construction began in 1958.

3,500

The number of apartment units within that same Beltway stretch that had been built by 1965.

“The magnetic popularity of the Beltway for business and industry could draw away activities that belong on ‘Main Street’ in the middle of town.”

—From a Washington Post news analysis the day before the Beltway opened, prophetically warning against the suburban sprawl that would soon come.

125,623

The number of total residents DC lost between 1960 and 1980.

Love in the Slow Lane

In the years since the Beltway’s opening, Korr says that engineers have essentially been playing catch-up with the road’s demands with strategies like adding lanes. In the meantime, Washington’s traffic has consistently been ranked among the worst the nation.

3

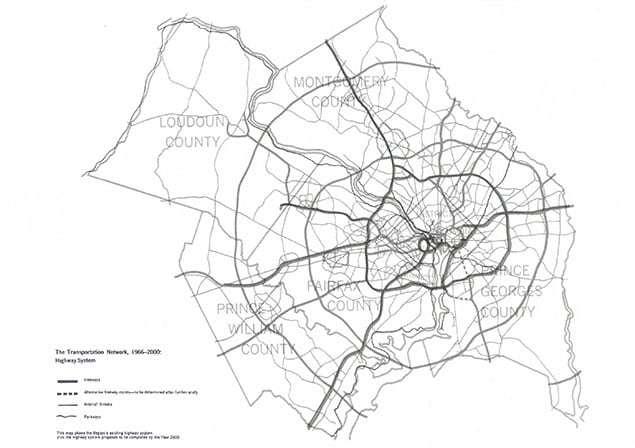

The number of circular Beltways planned for the Washington region. The Capital Beltway was meant to be the innermost one, with another outer ring and a third extending as far as Prince William and Howard Counties, plus a series of radial highways to connect them all. The second two Beltways and many of the radial highways were never built, owing to pressure from environmental groups and local residents who would’ve seen their neighborhoods plowed and paved over.

“The Capital Beltway was never meant to be a freeway in isolation,” says Korr. “That put stress on it that it was never intended to have.”

1984

The founding year of the Beltway Singles Club, which gave gridlocked drivers special window stickers to signal they were looking for love. Eligible rubberneckers, if they liked what they saw in the standstill, could call the club with the sticker number and request the other driver’s name and phone number.

626%

The increase in daily traffic since 1965 in the Greenbelt and College Park sections of the Beltway. Traffic there grew from 30,400 vehicles per day to 220,731 last year, the largest increase in Maryland. Like most sections of the Beltway, it was only widened once—from six lanes to eight.

23%

The highest projected increase traffic increase in any part of the Maryland portion of the Beltway. This section, at Persimmon Tree Road in Cabin John, is expected to grow from 220,751 vehicles per day now to 272,000 in 2040, according to the Maryland State Highway Administration.

“But the completion of the beltway does not ‘solve’ the transportation problems of the region. Rather, it redefines them . . . ultimately a mass transit system must be developed to supplement arteries subject to rush-hour hemorrhage.”

—From a Washington Post editorial on the Beltway’s opening day. It would be another 12 years before Metrorail began operation.