If you’ve been to the movies in the past decade, chances are you haven’t seen a film. Celluloid, the industry’s medium of choice for more than a century, has all but disappeared from American cinemas, with 95 percent of big screens already converted to digital projection and an ever-growing number of movies “born digital”—that is, shot on digital cameras. Since Paramount became, in January, the first major studio to embrace digital-only distribution for its domestic releases, other studios are expected to follow, bringing an end to films on film.

In Washington, the impact isn’t confined to the multiplex. To register a copyright, filmmakers must submit their work to the Library of Congress, which stores 123 years’ worth of American film—from Newark Athlete (1891) to The Expendables 3, due in August—at its 45-acre Packard Campus for Audio Visual Conservation, in Culpeper. Around the same time that Paramount’s The Wolf of Wall Street became the first movie to receive an all-digital release last December, the Library received a 35-millimeter copy.

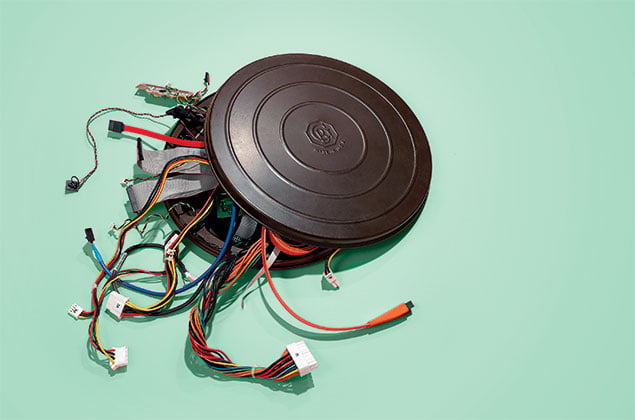

The rise of digital may soon require those copyright regulations to be rewritten. Already, says Gregory Lukow, chief of the Packard Campus, Hollywood is pressuring the Library to accept, instead of film prints, the set of computer files known as Digital Cinema Packages (DCPs), which studios send to most movie theaters instead of film reels. Encrypted to prevent piracy, each DCP can be played in one theater’s projector, at certain times, for a certain period. “It’s as good as a doorstop for us,” Lukow says.

His reservations about digital formats are shared wherever vintage films are stored, repaired, or shown around Washington—at the National Archives’ film center in College Park, which houses thousands of movies produced by the executive branch; at the Smithsonian, which specializes in anthropological films; and at the National Gallery of Art, where footage of Jackson Pollock and other artists at work is collected. For these institutions dedicated to preserving millions of miles of footage for posterity, the end of film signals a wrenching technical, cultural, and budgetary shift.

• • •

Anyone who has abandoned brittle, yellowing photo albums in favor of iPhones or the cloud might consider the film-to-digital shift a no-brainer. But for archivists, digital storage is a logistical headache. Once reduced to bits and bytes, information requires constant migration to keep pace with advances in technology, which tend to last no more than a few years. Lose the trail of upgrades and a film librarian, managing thousands of newsreels, shorts, and one-of-a-kind snippets, could lose access to an artifact entirely.

Add to this the fact that no one has come up with a satisfactory equivalent to old-fashioned film, which is a more robust, tangible medium than anything in the digital world. Archivists make repairs to decaying reels before copying the original onto polyester “safety” film stock. (Most film today, even what Hollywood types refer to as celluloid, is made of polyester.) Once they put the resulting print, called a preservation master, into cold storage, it can last several centuries.

“Film is simple,” says Criss Kovac, supervisor of the National Archives’ Motion Picture Preservation Lab. “It’s elegant. If we create a new copy and do the quality control, we know we can come back to it in a couple hundred years and it’s still going to be there, exactly the way it was when we printed it in 2014.”

The Archives’ collection of newsreels; documentaries; military recruiting films starring the likes of Jimmy Stewart and Ronald Reagan; and educational shorts about LSD, venereal disease, and forest fires together form a kind of collective national memory, which Kovac and her staff are charged with preserving “until the end of the republic,” she says. “The only way to do that is by using film stock.”

As digital takes over cinema, that commodity is harder to come by. Kodak, which is among the Library’s top suppliers (and the Archives’ only one), just recently emerged from bankruptcy. Though the company has no plans to abandon motion-picture film, the future availability—and cost—of film stock remains uncertain. Last year, Fujifilm ended production of movie film entirely. In recent years, the Library of Congress has had to rely on ORWO, a German distributor, but it deals only in black-and-white film.

“We’re going to continue to buy film stock for as long as we can,” says Ken Weissman, supervisor of Packard’s film-preservation lab. But he has already experienced “difficulties in catching Kodak in the right moment, at the right price, within our federal contracting regulations.” Kovac predicts that in the future “we’re going to have to be really selective about what we preserve.”

• • •

The film community has begun to mobilize around the challenges posed by new media. In 2007, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences released a landmark study, “The Digital Dilemma,” and called on filmmakers, curators, and studio executives to work together to create new standards for producing and preserving digital film.

The technicalities can be daunting. A format called a Digital Cinema Distribution Master (DCDM) is being offered as an alternative to the DCP. Akin to the original camera negative—the strip of film that goes through the camera on a movie set—the DCDM, unlike the DCP, is not encrytped. But Weissman points out that the DCDM has its own problems. For instance, it doesn’t allow the Library of Congress to add closed captioning and subtitling, which the Library is legally obligated to offer. Accepting DCDMs would force the Library to create foreign-language versions of films in-house. “A laboratory like ours is really not geared towards that,” says Weissman.

There’s also the relative cost of digital to consider. Movie studios like digital distribution because it’s cheaper: A DCP will eventually take less than $100 to produce and deliver to theaters, compared with $1,000 for a film print. But digital formats are much more expensive to preserve. The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences estimates the annual cost of maintaining a digital master at $12,500, 11 times that of film.

Archivists have already begun to work together to accommodate digital formats. In 2010, the Archives completed a decade-long effort to preserve the entire Universal newsreel collection after the Library of Congress supplied some missing reels. Members of the Association of Moving Image Archivists, the National Film Preservation Board, and other professional organizations regularly meet to hash out the future of film and digital preservation.

But more cooperation is needed. “We don’t really have any interagency agreements in place to help each other out,” says Kovac, though she’s hopeful that, as more problems arise, government-funded archivists will pull together.

• • •

Until the technical questions are answered, the resistance to digital media is more than a matter of nostalgia. But some movie experts think the efforts to adapt to digital ignores the relationship between cinematic images and their medium.

Peggy Parsons, head of the National Gallery of Art film program, regards the studios’ move to digital as “a distortion of history.” For her, film’s character—its grain, scratches, wear and tear—grants a physical connection not only to the filmmaking process but also to the times and places a movie was screened. “You’re having a much more profound experience when you’ve got the real artifact,” Parsons says of film projection. “You can feel it in your mind and body. It isn’t just what the actors are doing or what the story is. It’s an experience of the whole medium.”

The National Gallery hosts free, weekly repertory-film screenings, for which Parsons always tries to acquire a movie in its original format, to “replicate the historical experience as closely as possible,” she says.

Lukow and Weissman sympathize but view Parsons’s purism as a distraction. “People talk about the unique look and dynamism of film, but for the most part that’s been lost for decades anyhow,” Weissman says. With brighter projector lamps and modern screens, he points out, a film will never look to us the way it did to its first audiences.

He and Lukow agree that the movie, not the format, comes first. “The essence of the film is the content,” says Weissman. “It’s the images that are recorded on it, not the fact that it’s film per se.”

Those sentiments may sound out of place at Packard, which opened in 2007 to be, in Lukow’s words, America’s “last place standing” for film. The Library of Congress remains “committed to preserving film as film as long as we can,” Lukow says. “At the same time, we recognize that we have to position ourselves for the post-film world.”

This article appears in the September 2014 issue of Washingtonian.