A little garden sits just behind Firehook Bakery in Cleveland Park. It has tables, chairs, and lattices with grapevines. There’s a fountain and a mural of Italy. Most customers who come back with a coffee probably have no idea they’ve entered the last link to one of the most unusual Italian restaurants in America.

Frank Abbo opened the Roma on F Street downtown in 1920, and in 1932 it moved to Connecticut Avenue, where he expanded to five storefronts: the original room with booths and a bar; a second for overflow; a third for banquets, with a door to the garden; a raw bar; and Poor Robert’s Tavern, named for Frank’s son, Bobby.

I moved to DC in 1974 and bought a rundown house. My wife and I tore out the kitchen, then realized we couldn’t cook. On Thanksgiving that year, we went to the Roma. The Abbos had decorated with paper turkeys and pictures of pumpkins. We smirked a little because we were young and everyone looked over 70. Today’s foodies wouldn’t care much for the menu: spaghetti, meatballs, red sauce on everything, baskets of bread, cheap wine. Maybe it was uncool, but it was authentic.

On summer nights in the garden, a soprano strolled with an accordionist, singing arias from La Traviata and La Bohème. If you couldn’t get a seat, you could listen to the blind woman playing piano in the main room and hear songs such as “Love, Your Magic Spell Is Everywhere.”

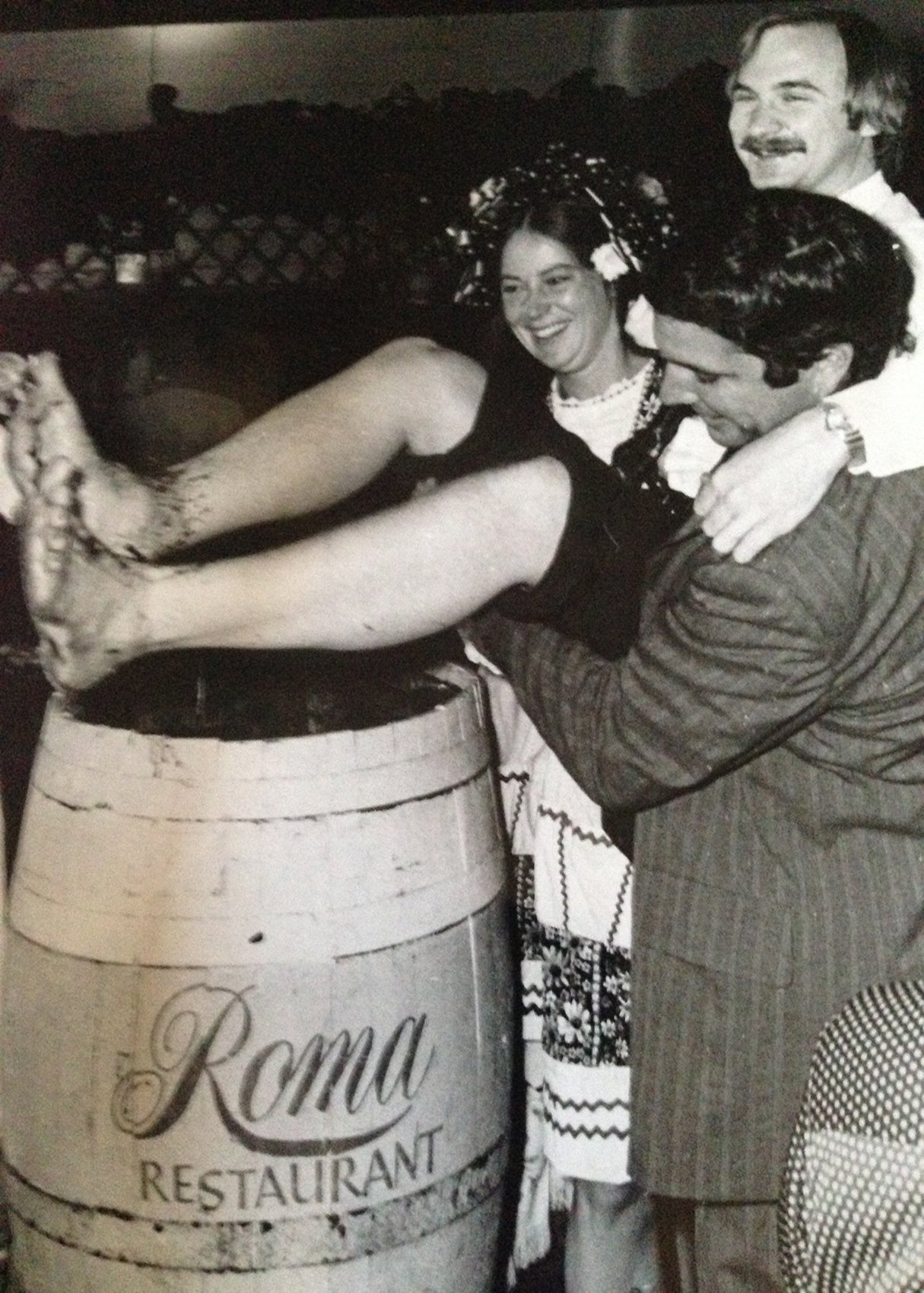

Every September, the Roma held a wine festival. A barrel of grapes in the garden invited guests to take off their shoes and stomp—just like Lucille Ball in that episode of I Love Lucy. The accordionist played “La Tarantella” as Washingtonians—many tipsy—lined up to get into the vat. Channel 4 sent me there many years to stomp grapes in the name of first-person journalism.

If you went into Poor Robert’s and wanted to place a bet on a horse or a game, somebody could arrange it. Bartender John Squitero held a position of honor, if for no other reason than his nickname, Johnny the Squid. Poor Robert’s had one of the first satellite dishes, and it didn’t use it to watch HBO. It was strictly for sports viewed with an eye to the point spread. The men’s room looked like the one where Michael Corleone hid a pistol in The Godfather.

In 1970, Frank Abbo took a phone call, ran out into Connecticut Avenue, was hit by a car, and died. The driver raced from the scene, and the death remains unsolved. A reporter drunk on wine once asked Bobby if the Mafia had killed his father. Bobby shook his head, got up from our table, and walked away.

Frank Abbo’s spirit hovered over the place, especially because of the animals he killed on safaris and hunts. In the front window as you walked in was a collection of stuffed creatures—a polar bear, a leopard, an elk, even a dik-dik.

With Frank gone, Mrs. Abbo ran the Roma with a firm hand. Doug McKelway, the TV reporter and a native Washingtonian, told me he and his high-school friends once came in and ordered a pizza. Before the check arrived, they ducked into the garden and down the alley. When they got to the street, there stood Anna Abbo. They paid.

The Uptown Theater across the street brought a crowd for premieres, and Mrs. Abbo came for every one. Dick Tracy included an appearance by Warren Beatty and Madonna. As I set up on the red carpet, I felt a tap on my shoulder. It was Mrs. Abbo. “Whatsa happen?” she said. “Whosa come?”

“Oh, Mrs. Abbo—it’s Madonna.” Anna repeated the name Madonna and planted herself next to me. When the Uptown held a premiere, Anna Abbo found somebody to watch the cash register.

Bobby’s wife, Marcia, whom he’d met at Poor Robert’s, endured the stink eye from his mother for the rest of Mrs. Abbo’s life. I once asked Marcia how she got along with this tough woman. “She never spoke to me directly,” she said, “and she referred to me as Marshall as long as she lived.”

For decades, a truck full of turkeys pulled up in front of Bobby’s house on Thanksgiving. Church groups and charities came for his turkey giveaway. Bobby created Poor Robert’s Charities, hosting a fundraiser—first at the restaurant and later at Columbia Country Club. Over the years, he got to know almost all of Washington as he went from table to table.

No one anticipated Bobby’s announcement in 1997, not long after his mother’s death: The Roma was closing. The family owned the property, and now Bobby would manage it, renting the space to other businesses. The Roma had languished in its final decade as new, fancier places opened. But in the last weeks, the place filled to capacity. I brought a camera crew to record the final night. The soprano sang her arias. The blind pianist played the old songs: “Kiss Me Again,” “Love Walked In,” “Always.”

The next day, an auctioneer sold everything—dishes, tables, even the animals. A Washington Post writer ran up to me and bubbled, “I just bought a dik-dik!”

Bobby and Marcia lived in Florida for the winter but came home each summer. He pruned the grapevines in the garden, by that time used by Firehook. He stayed long enough to give away his turkeys and host his Poor Robert’s event. Years passed. Bobby suddenly slowed down. My friend died of leukemia in April 2014. His wake and funeral looked like the crowd at the Roma on a busy night.

In addition to Firehook, the space now houses other restaurants—Ripple, Fat Pete’s BBQ, Byblos Deli—and a pottery-painting studio. But the garden remains: a spot in an alley that an eccentric family turned into paradise. You can visit for the price of a cup of coffee.

This article appears in our August 2015 issue of Washingtonian.