Turn on the Investigation Discovery channel and there’s a good chance a woman is getting killed.

On Wives With Knives, Scorned: Love Kills, and Fatal Vows, people kill their partners. On Blood Relatives, Evil Kin, and Evil Twins, people kill their family members. On Elder Skelter, old people kill each other. On Murder in Paradise, people whack each other on vacation. On Do Not Disturb: Hotel Horrors, the act is done in fancy hotels. All day, all night, people—often women—get abducted, raped, murdered on the true-crime network.

And all across America, female viewers can’t get enough.

Launched nearly eight years ago from the Silver Spring headquarters of the sprawling media empire Discovery Communications, Investigation Discovery quickly became one of the fastest-growing cable networks in the US. Among women ages 25 to 54, it went from number 50 in ad-supported cable channels to, this past September, number one. That means women like it more than they like TLC or Food Network. More than Lifetime or Oprah.

And, somewhat amazingly, the channel’s honchos—senior VP of development Jane Latman and her deputy, Winona Meringolo—have succeeded by making ID utterly formulaic. This may be a golden era of sophisticated, scripted TV blockbusters, but across the ID network, nearly every program follows an essential, inviolable pattern of recreations, sometimes comically ominous voice-overs (“But who would want to murder the well-to-do family?”), zigzaggy plots, and a tidy ending.

Go ahead and laugh, you up-market binge-watchers of Netflix and HBO. But if ID’s hallmark brand—the frothy, exploitative guilty pleasure—seems out of touch, it still has a lot to tell us. The cautious, savvy duo behind Wives With Knives have developed a very subtle understanding of what keeps women frightened—but not too frightened—hour after hour after hour.

• • •

Like many of its parent company’s channels, ID began life in the 1990s as a well-meaning educational venture.

Then known as Discovery Civilization, it ran documentaries on ancient peoples. Unsurprisingly, it was not widely watched. In 2002, the New York Times bought a stake, switching the network’s focus to current affairs, but bailed out a few years later.

By 2007, Discovery was desperate to reinvent the channel again. Crime-and-justice programming had worked well for Discovery’s namesake network, and there was some logic to building an entire channel around it. For decades, Americans had proven themselves willing to stay up late for shows like America’s Most Wanted. Then, in the 1990s and 2000s, Court TV built an avid fan base through its post-O.J. transformation into an ESPN for tawdry crime coverage. But it had lately embraced a reality-TV model, leaving the field wide open for a wall-to-wall true-crime bonanza.

Latman, who has been at ID from the beginning, says there was some early experimentation with what ID would, and especially wouldn’t, be. Forensics-oriented shows and procedurals largely disappointed. So did a history-of-mysteries show. A laid-back presence, Latman herself wasn’t exactly the target audience. She has never been particularly into crime—she likes love stories, including scripted dramas and romantic comedies. But at 47, she’s been in TV a long time, previously having worked for years in DC’s theater scene as a director (and as a bartender, at Paolo’s in Georgetown). Based partly on the storytelling lessons she gleaned in theater and a lot on gut, she and general manager Kevin Bennett gradually shaped ID into its real-life-stories form. “When it comes to murder mysteries, what works better is personal,” she says.

A year and a half into ID’s run, Discovery hired Henry Schleiff, the former Court TV CEO, to run the nascent channel. He described ID as “a sleeping giant” that should be in the top ten. Pestering his bosses to invest, Schleiff upped its hours of new programming from 258 in 2008 to 681 this year. He jazzed up the titles of original shows (Wives With Knives is a Schleiff classic) and signed on celebrities (Roseanne Barr hosts a program called Momsters: When Moms Go Bad). “He used to say, ‘You’re all a little bit demure,’ ” Latman recalls.

The tweaks delivered the ratings Schleiff had promised. In six years’ time, ID was number one among women 25 to 54. ID also has one of the longest “lengths of tune” in the industry: Women watch for an average of 52 minutes, almost exactly the duration of most ID shows. The cable average is 27 minutes. So at a time when more TV watchers are grazing through streaming services, people consume ID the old-fashioned way—from start to finish, and often in real time—to the extent that, according to letters sent to ID’s “viewer relations” people, the little channel’s logo gets burned into their screen.

“People watch ID a little like they binge-eat candy or popcorn or something,” says Abby Greensfelder, who runs a TV production company that makes shows for Discovery. “There’s a certain kind of viewing state.”

It turns out women will gladly eyeball other women getting abducted, raped, and killed for hours. And ID has nailed the exact science of making such brutality an enjoyable, even addictive experience. The biggest reason, everyone agrees, is the emotional punch ID delivers. “It doesn’t matter what that emotion is,” Schleiff says. “You can be mad, you can be upset, you can be intrigued, you can be mesmerized, but it’s got to pull you in.”

Often the emotion is fear: True-crime author Rebecca Lavoie, who has appeared on ID shows as an expert, describes the channel’s appeal as that of the universal “parable” of the “bad man.” Says Lavoie: “I think most women in their lives have been in a bad relationship that either felt off or went really bad, and watching these stories sort of lets you play that out.”

Jennifer Norris, a regular #IDAddict tweeter and a survivor of military sexual abuse, notes that other superfans she has corresponded with are also survivors of crime. “These shows help me see that I am not the only one that was crushed by the crimes of these people,” she says by e-mail. “They validate the way that I feel.”

ID being ID, though, the fear and victimhood invariably turn into something positive. On a 2014 episode of Deadline: Crime With Tamron Hall, after a Jamaican pediatric nurse was viciously murdered, it took years for a young man to come forward with information leading to the apprehension of her killers. In the last scene, the tipster and the nurse’s family finally met, under Hall’s gentle guidance. Whereas the rest of the show was a CSI-ish thriller of cops and bad guys, the conclusion approached the soapy catharsis of great theater—Hall says the episode was her all-time most popular on social media.

• • •

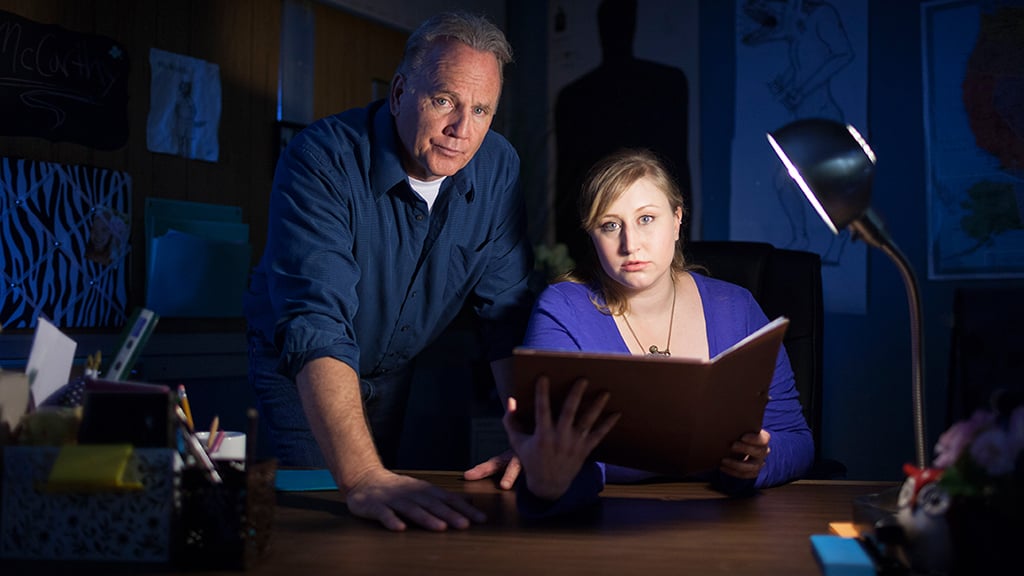

One day this past fall, I drove out to a farm in Frederick to see how a typical ID show comes together.

Sirens Media, a Silver Spring company that works hand in glove with the channel, was shooting House of Horrors: Kidnapped, a series about women (mostly) who are abducted and escape.

Today’s filming involved what in ID-speak is a “recree”—a recreation scene. A character named Kirk has lured a young woman called Jessica to a creepy farmhouse where he has just murdered his mother. Via a camera in the back seat, we watch him hustle her to her car, her wrists wrapped in twine. Resourceful Jessica convinces Kirk to stuff her into the trunk, where she knows she has a bag of tools she might use to thwart him. Unfortunately, Kirk yanks the tools out, leaving her in despair.

Rather than bring in Hollywood actors, producers draw on a stable of local talent for such scenes. Vince Eisenson, the actor who plays Kirk, says he’s done Nightmare Next Door four times: “I was a roommate twice. And then a red herring. And an extra. So never the nightmare!” Not yet, at least.

On the set, the actors were friendly, even flirty. Awaiting cues, Eisenson rested his hand on actress Adrianna David’s back. Then the cameras began to roll and Eisenson’s long, craggy face went terrifyingly blank as his character wrestled Jessica to the car, muttering, “You want it? Okay!”

The twists and turns of Jessica’s story (She wanted the tool bag! Tool bag tossed out of her reach!) were only part of what made this a classic. There was also Eisenson’s blandly evil villain and the relatably cute victim—feisty David, pretty black tendrils framing her face. Then there was what series producer Jennifer Anderson calls “takeaway.” It’s something they look for in all the real-life stories they choose. A moving happy ending, a testament to the human will to survive; some kind of redemption to leaven what are often otherwise incredibly brutal tales. Frequently, too, the stories seem to seek out helpful object lessons in how not to get kidnapped. Short version: Don’t get into a car with the creepy dude.

Sirens has been creating ID content along this pattern for years now. Their hits include Who the (BLEEP) Did I Marry? (a staple of the “oops, my husband is a criminal” genre) and Southern Fried Homicide (“Murder . . . with manners,” according to their website). “I’m probably as seasoned now as Jane and Winona,” Valerie Haselton, co-president of Sirens, says. “When I hear a crime idea, I don’t always know if they’ve heard it, but I know pretty quickly if it’s a good one and if it’s good enough for ID or not.”

It’s not hard to figure out. Most shows are structured around specific rules. Meringolo, a major crime buff, left Discovery’s TLC network for ID about five years ago. Early on, she asked the ID team how they defined the ideal show: At TLC, this so-called “filter” had been easily summed up in three intersecting themes, but at ID, she says, the filter is more like a “stew.”

It’s true that the ur-ID show can feel like a complex stew of ingredients. There are the low-budget “recrees” and the interviews with experts and family members as well as the victim, if it’s what execs call a “non-murder” show. There’s nearly always a suggestive voice-over narration, sometimes provided by a comforting host such as the avuncular Lieutenant Joe Kenda on Homicide Hunter. Plot twists carefully pegged to commercial breaks. Recaps when you get back. Also, a red herring so it’s not immediately obvious whodunit.

On top of that are various generic rules, some derived from the Henry Schleiff book of narrative theory, others from years of studying ID’s audience. Certain types of crimes and criminals will never fly. For instance, the network does very few crimes involving children. “It’s just too sad, and the audience will just push back,” says Schleiff, who also thinks straight revenge is a bummer. “He calls it sad upon sad,” Meringolo says. Nothing too random, no spree killings, no coworkers going postal.

That rule came into play after Discovery’s own 2010 hostage situation, when a gunman stormed into the building and held several employees before ultimately being killed by police. The incident gripped the Washington area—Latman remembers having to shelter in place that day—but the assailant’s mental state put him out of bounds for an ID recreation.

You can tell pretty quickly when someone’s ideas don’t measure up. In September, I traveled to New York to watch Latman and Meringolo bat around ideas with Chris Hansen, whose NBC show, To Catch a Predator, had been dropped after one of its targets committed suicide. Now Hansen was shopping a program called Hansen vs. Predator, something very similar in concept to the NBC original, in which would-be pedophiles are lured to phony meetings. Hansen already hosts an ID newsmagazine show, but the execs were clearly not buying this one.

“Wow,” Latman said after he mentioned it. When he kept bringing it up, Latman added, “Good luck,” in her most indulgent, comforting voice. ID rarely does anything with hidden cameras, or pedophiles.

Beyond controlling for the mechanics of who does what to whom, there are some more general dictates. The victims’ relatibility is key: Their actions must stay within a whisker of what a viewer can imagine doing herself. (“Down-market” subjects were mentioned in more than one meeting as a no-no.) And most important, what happens to them can never be their fault.

At another New York pitch meeting, I watched a male production-company employee run afoul of this rule. His idea was a subtle paradigm shift for a new show. “I think traditionally the women have been very innocent in almost all the shows you do,” he said. “But this time around, you’ve actually got a potential to say, ‘There’s something in these woman’s pasts that have triggered this. Are they 100 percent innocent?’ ”

Latman just listened with her fingers tented, but later she told me the comment “raised my antennae.” ID does not do victim-blaming. For the record, you’re also meant to find the cops entirely good. As Valerie Haselton said, “Sirens and ID tend to be friends of law enforcement”—you generally don’t see police botching a case. These black-and-white story lines then feed neatly into the tidy, law-enforcement-enabled resolution of justice.

• • •

It’s a complicated time for pop culture’s depiction of police.

The news is full of calls for new scrutiny of law enforcement. And the most talked-about crime program of the day is Serial, the 12-installment podcast that in its first season re-investigated the kind of Baltimore murder whose details would be all but impossible to boil down to a neat 30-minute recreation.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Latman and Meringolo weren’t completely sold. When Hansen mentioned it as the “engrossing” storytelling he wants on his forthcoming ID show about wrongful convictions, Meringolo said: “I think that . . . unlike Serial . . . we’re going to be able to actually bring some conclusion to [your show], which you know our audience loves. And that’s what felt so—you saw it at the end of Serial, the audience was like, ‘Wha—? That’s it? That’s all?’ ”

And yet Serial, The Jinx, and darker scripted TV shows such as The Walking Dead—with their gray areas and muddy endings—are defining the programming landscape right now. In this environment, ID is old-school, like a pulp novel compared with a literary thriller. While the formula has drawn millions of fans, it can also prove problematic. At times, ID has lost sight of the actual facts of the case. Rebecca Lavoie and her husband, Kevin Flynn—also a true-crime author—have written books that shows have been based on, and both say production companies working for ID futzed with details in their recreations. This ranged from putting a character in a negligee to emphasize her sexy gold-digger side to “significantly” altering the timeline of a murder to create a big reveal at the end, Flynn says.

Last year, Sirens producers debriefed with Lee Moon-Griffo, the sister of a murder victim, for an episode of Deadly Affairs with Susan Lucci. When Moon-Griffo saw clips from other episodes and “realized it was ridiculous in the cheese factor,” she worried about how the crime would be portrayed. Watching the final result, Moon-Griffo says, she was appalled.

Along with some small inaccuracies, there was the larger problem that the show misframed her sister’s murder, she says. While Moon-Griffo viewed it as the tragic outcome of a physically abusive relationship, ID made it a sordid love triangle gone bad. “To conflate [domestic violence] with passion and sexuality in such a soap-operaish kind of way, with soft filters and suggestive language to try to make it sexy—I don’t think it’s just offensive to me; I think it’s dangerous,” she says.

After she wrote about her experience in an xoJane.com column, ID yanked the episode from the air. Latman says she found the article “upsetting” but points out that ID also gets “hundreds of letters from families who are happy and pleased” about sharing their story “and the way it was treated.”

It may be, though, that ID’s narrow story lines risk boxing women in. Lavoie points out that the typical “evil woman” plot on shows like Momsters does a disservice to the complexity of female crime, given that “we know that most women who commit crimes were victims of crimes or abused.” (ID has also done more complex shows such as Women in Prison, however, asking viewers to identify with sympathetic female criminals.)

Moreover, the sheer number of passive female victims on ID can feel deadening, even if their attackers are eventually brought to justice. When I asked Latman if her channel’s high female body count was something she thought about, she got quiet. “Yeah,” she said. “I’ve been thinking about it lately.”

• • •

Investigation Discovery has tried tinkering with its tone.

A little more than a year ago, Latman and Meringolo went lighter, introducing a bunch of new shows focusing on “crimes of morality”—complex events, such as a prostitute potentially selling out a celebrity client for money and fame. Schleiff let them experiment but was skeptical. “He was banging the drum: Stick to your knitting, stick to your knitting, stick to your knitting,” Meringolo says.

Only one, Cry Wolfe, a more playful take on the usual private-eye/recreation shtick, did well. What #IDAddicts want, Meringolo summed up, is “the high stakes.”

So the team doubled down, to make ID even more psychologically stark. Latman thinks darker is working right now because of a broader cultural evolution—not just the gloomier shows on TV but something in the ether, “a lot of fear and uncertainty.” Meringolo adds: “I think people feel that there is an escalation of [fear]. That there is so much that they can’t control.”

At a brainstorming meeting with Sirens in September, Haselton floated a show about a female duo who work on, essentially, saving families from really bad situations. (Discovery asked me not to reveal the specifics.) As she watched a sample clip, Meringolo’s eyebrows were on high alert. These were very unenviable scenarios but, for ID, involved relatively low stakes, such as addiction or abusive relationships.

“In our world, cheating, infidelity, double lives—they lead to more serious consequences,” Meringolo said. “So when they watch a story where [cheating, infidelity, and the like are] what you’re building towards, it feels like fluff to them. They’re like, ‘All right, that’s it?’ ”—eyebrows shooting way up.

Talk turned to a show about competitive women killing each other, and everyone debated how to make it as diabolical as possible. “I’m seeing a lot of recree, very recree-heavy,” Haselton enthused, “and you play it like the Stepford Wives film or something, where on the surface everything looks normal but everything is deeply wrong.”

Latman, sounding a bit concerned: “But we’ve got to feel—we’ve got to feel scared.”

Meringolo: “Darker than Stepford.”

Haselton said, “Got it,” and in her notes wrote, “Go dark.”

If there’s any production company that encapsulates the slightly new direction ID is trying to take, it’s probably October Films, which has three new “psychological” ID shows. In Obsession: Dark Desires, the only interview subject is the protagonist, someone who has been brutally stalked. The perspective is highly subjective. Through distorted horror-movie effects and tricks of space and time, you experience the helplessness and vulnerability of being stalked, just as the victim does.

“These are stories of . . . the most intense crimes, and we felt that once you’d met these women and started talking to them, why would you ever leave her story, go to a detective or a neighbor or a sister, when you have everything right there?” says October’s creative director, Matt Robins.

Dialing back to one interview subject, in a show that’s still structured like most others—tidy resolution and all—might not seem like a major creative risk, true. Given ID’s obsessive audience and its loyalty to the precise formula, however, it actually could have been. But Latman and Meringolo pretty much instantly got onboard. “It was still the kind of storytelling and emotion that we go after,” Latman says. “And the emotion was even more intense.”

The risk paid off: On for two seasons now, Obsession is one of ID’s highest-rated series.

• • •

As I was writing this story, I spent weeks binging on ID and began to feel both extremely anxious (alone in my apartment—what was that sound out in the hall?) and also empowered.

If there was a serial killer in my hallway, at least I had just watched an ID show in which a girl talked her way out of being serial-murdered, so I would know what to do!

This knowledge was not soothing, though. In fact, it was an added source of anxiety. I felt as if I had to remind myself frequently so as not to forget later under tense circumstances: Plant the DNA evidence around his apartment for future investigators, tell lots of tragic stories about your family to humanize yourself—and once he drops you off on the dark street corner, run for your life!

Both Latman and Meringolo know what I’m talking about. Latman told me she got an alarm system for her house in Takoma Park since starting at ID, that “we all have nightmares,” that sometimes “it gets through and you find yourself having a good cry.”

Meringolo, who said she’s always been a little paranoid about things like riding Metro by herself (“My husband was very concerned about me starting at ID”), doesn’t have any kind of internet presence and booby-traps hotel rooms. How? “I’m not going to say what I do!”

In September, I watched the development team try to plan its annual movie outing. Latman suggested a forthcoming Julia Roberts film. Meringolo just said, “That will probably be in—” and before she could finish the sentence with “a movie theater,” Latman immediately apologized.

“What’s up with movie theaters?” I asked.

“There are a lot of killings happening in movie theaters right now,” Meringolo told me, her arched brows announcing what was obviously lifesaving advice for the clueless. “In closed spaces. Hatchets. Whatever.”

Of course—what was wrong with me? Why hadn’t I known more about the hatchet/movie-theater killings? I should be more prepared.

In gentle, almost maternal tones, Latman said, “We all have our . . . .” and trailed off.

Contributing editor Britt Peterson (@brittkpeterson on Twitter) also writes for the Boston Globe and the Atlantic.

This article appears in our December 2015 issue of Washingtonian.