Bug Man Pete and I are out on the front porch at Hank Dietle’s Tavern, the last roadhouse in Montgomery County, watching the traffic crawl by on Rockville Pike.

An exterminator by trade, he’s finished battling vermin for the day and is ready for a few cold ones. A pitcher of draft beer is on the table, and a lit Maverick cigarette is in his hand. He’s feeling good, as he usually is at Dietle’s.

Bug Man Pete (real name: Peter Carlson) has been coming here for almost half of his 56 years. But people like him have been coming to Dietle’s for a century. They were here when the Pike was a rural toll road. They were here when cold, cheap beers were illegal. They were here when Metro dug its tunnels underneath and when a gleaming new mall went up across the road. Now that the mall has been shuttered, they’re still here.

As it happens, White Flint Mall is on Bug Man Pete’s mind today. When it opened in 1977, as Montgomery County’s suburbs marched triumphally away from DC, it was the glory of its time. With its triple-tier design, glass-encased elevator, and boutique stores, White Flint was upscale to the hilt. The mall was a $50-million gamble that paid off royally for decades.

Now, though, the mall is being razed to make way for a chic, pedestrian-friendly condo-and-retail development. It’s moving too slowly for Bug Man Pete, who takes no small pride in the fact that his favorite hangout is still standing as the mall is reduced to rubble. “I wish they’d implode the damn thing and get it over with,” he says.

Pete tells me he saw it all coming, and his gloating turns to cold diagnosis: “The last time I was at White Flint, I looked around and everything that was offered was nonessential. Maybe stuff you wanted, but there wasn’t anything in the whole mall that you really needed.”

Here at Dietle’s, though, the business is still viable, at least to Bug Man Pete’s thinking. Such a notion would sound insane to someone—and there are many—who walk into a bar like Dietle’s, try to stifle a shudder of revulsion, and walk back out. They’ll never know the uncanny, gravitational force a place like this can have on some of the rest of us.

“There’s a huge difference between what you want and what you need,” he says. “Everyone—well, generally speaking, everyone—needs a beer once in a while, and sometimes you need a beer and some peace of mind. At Dietle’s, you can get both.”

Bug Man Pete points with his smoldering cigarette to the entrance, with the sign overhead that reads established 1916, and says with the finality of a closing argument, “It’s a place that you know is gonna be there. When I walk through that door, I can get away from it all.”

While I don’t fully subscribe to Bug Man Pete’s theory of the fundamental wants and needs of mankind, I know exactly what he means about Dietle’s.

For more than 20 years, I’ve come to this ramshackle building, which marks its 100th anniversary this year, and it always hits the spot.

The bar is a dimly lit, one-room, linoleum-floored clubhouse with dark wood-paneled walls cheered by strings of low-watt holiday bulbs. The feel is midcentury rec-room deluxe, a cozy time capsule from the era when Elvis dwelt among us. It has a pool table, a jukebox, a pinball machine, and video games. The rickety, bare wooden booths have so many initials and names scrawled on them by patrons that the overlapped etchings are as inscrutable as ancient runes. The decor is strictly use-what-you-got, such as the faded beer-price-list placard from yesteryear now serving as a window shade. Captain’s chairs line the worn, unvarnished mahogany bar, which, legend has it, dates to the Civil War and was imported after a 1940s fire from a Baltimore waterfront bar.

I’m always amazed at the sheer inertia and immutability of Dietle’s, greeting me with its serene sameness even when it’s been more than a year between visits. The place seems immune to the seismic changes outside its walls, as if protected by the blessed hand of God’s Own Drunk.

Sometimes I come here by myself, and it’s a simple but elusive joy to sit at a bar and drink a beer alone and not have to worry about not wanting to talk to anybody, including the bartender. Other times, it’s a place to meet friends I haven’t seen for a while. One complained that the bar wasn’t redneck enough. But that’s exactly the point. Dietle’s defies conventional wisdom by attracting a wildly varying clientèle—scientists from nearby NIH and bureaucrats and blue-collar holdouts and carloads of slumming college kids and oddball iron-ass regulars, such as the ex-Nuclear Regulatory Commission employee and hothead who was banned not once but twice from the Bethesda Tastee Diner for verbal belligerence but is still welcome here.

“It’s the Twilight Zone,” shrugs Tony Huniak, the mild-mannered, even-keeled proprietor of Dietle’s for nearly 20 years. “Some people call it a dive bar or a roadhouse, but it doesn’t really matter what you call it. It is what it is. It’s just a little hole-in-the-wall bar on the Pike that sticks out like a sore thumb.”

For sure, it’s never been a contender for Neighborhood Beautification Award. The squat, cottage-like bungalow sits crouched along the road like a possum playing dead. Yet it’s Dietle’s homely but who-gives-a-rip aspect that helps keep the place alive and kicking. The hangdog look, especially compared with the new breed of brewpubs down the Pike, is what attracts a certain type of diehard customer. Washington’s many transplants drive by Dietle’s, and its ramshackle appearance—reminding them of some old beer joint from their hometown—draws them in: Is that goddamn place still open? For these pilgrims, Dietle’s is a dive-bar version of Marcel Proust’s madeleine, evoking memories of that long-ago and faraway first whiff of Schlitz.

That’s what brings Steve Berry here on the occasional Saturday night. A lawyer who lives in Brookeville, he grew up in Richmond, Indiana. Dietle’s takes him back to the watering holes around the cornfields of Wayne County. “You could plunk this place down anywhere in Indiana and it would be anyone’s hometown bar,” Berry says. It’s a refrain you hear a lot from fans of the place, such as the guy who swears he knows a tavern south of Pittsburgh just like Dietle’s, something out of The Deer Hunter. As a Virginia transplant to Maryland, I’ve seen distant—and far uglier—cousins of Dietle’s on country roads across the Old Dominion.

For Brendan Gillen of Kensington—a Marine veteran of two tours in Afghanistan and still in his twenties—Dietle’s is a refuge from the big-chain sports bars where the bouncers cop the same badass attitudes as their liquored-up patrons.

“It’s down-to-earth and down-home, like one of those small-town South Jersey bars,” says Gillen, whose only beef with Dietle’s is that the pool table is a tad warped. “No one’s in your face, and they don’t have to try to sell you food. Just peanuts and chips like they’ve got here—that’s all you need.”

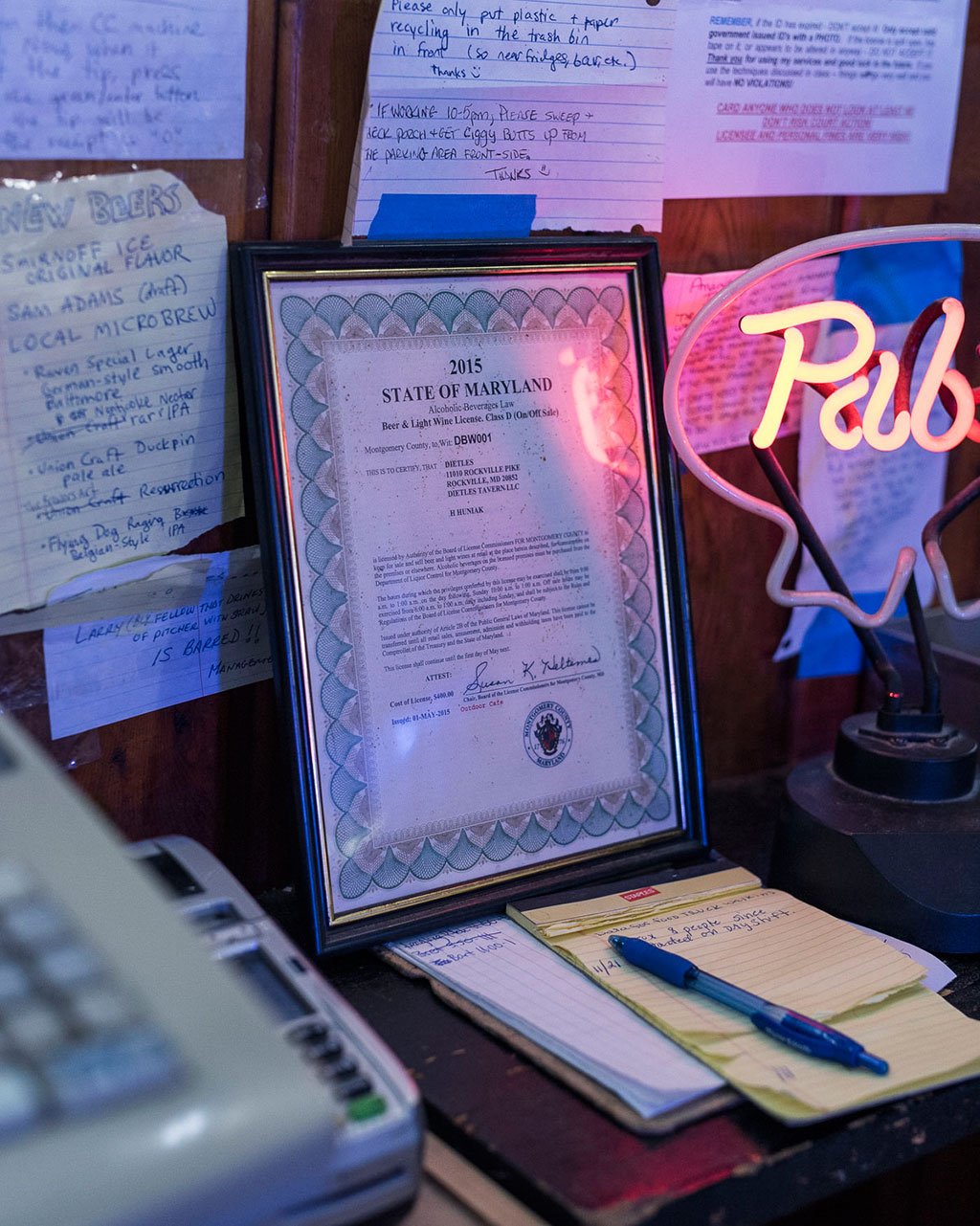

This is no country for foodies. In fact, it’s not even hospitable for people craving a microwaved hot dog: Unlike many other drinking establishments in Montgomery County, Dietle’s is exempt from the requirement that bars make 40 percent of their revenue from food. Its Class D beer-and-wine license, numbered 001, is the first issued after the end of Prohibition, making Dietle’s the oldest bar in Montgomery County. Framed on the wall next to a bottle-shaped Miller Light sign, it’s the Magna Carta of the business, allowing it simultaneously to forge ahead and to remain anchored in the past.

More to the point, it allows for the sale of beer and wine—and here’s the crucial line—“for consumption on the premises or elsewhere” from the 9 am opening (10 on Sunday) 365 days a year. Thus, the modest hank dietle’s cold beer marquee out front has been a beacon for the masses on the move who could quench their thirst either at the bar or with a six-pack to go. A well-dressed brewpub should be so lucky.

Dietle’s opened in 1916 as Offutt’s, a general store and filling station.

Back then, Rockville Pike was a winding toll road that followed the old 19th-century stagecoach route from the tobacco fields around Frederick to the port at Georgetown.

At Offutt’s, farmers could stock up on feed for their livestock, groceries for their families, and beer for themselves. Photos show a building remarkably similar to today’s Dietle’s, right down to the front porch. From there, you could see a procession of modern American history go by along the Pike—from the last of the horse-and-buggies and the first automobiles to the motorcade that carried Eisenhower and Khrushchev at the height of the Cold War to the car dealership nearby where the Beltway snipers gunned down their second victim and fled in their 1990 Chevy Caprice customized for long-distance killing.

By the time Hank Dietle took over in the ’50s, the Pike carried 16,650 vehicles a day. It was the beginning of modern traffic gridlock and a boon for the tavern, which became a pit stop for harried motorists. When the Beltway was completed in 1964, the to-go business thrived, as Dietle’s was the last spot where you could buy beer before the exit to 495. That same year, a local politician declared the Pike “the ugliest place in Maryland.” Dietle’s fit right in.

Even so, it was the sit-down-and-drink crowd that made Dietle’s into a bona fide institution. For generations raised in the area, it was where you had your first beer and your first buzz-on, and sometimes, as a result, you had your first DUI. It was a place for the men to commiserate after being banished from home as wives prepared holiday meals. Over the years, Dietle’s was like family.

In its heyday in the ’60s and ’70s, it also had a reputation as a rough-and-tumble joint that many locals would glimpse only when they dropped by for a six-pack to go. The pool table sparked the usual scuffles, but sometimes it got more serious. In 1972, a Bethesda fireman was shot and killed in the parking lot after an argument over whose turn it was to use the table.

By the late ’70s, Dietle’s looked increasingly out of place in the neighborhood. White Flint Mall was across the street, having overtaken a golf course where teenagers once harvested skunk weed. Workers spent the decade tearing up the Pike for Metro’s Red Line, whose nearby stops opened in 1984. Naturally, they came to Dietle’s at quitting time. By now, it had outlasted a slew of bars along the Pike that had bit the dust: the Belbey House, Agnew’s Inn, the Pike Pub, Seven Clocks. All gone.

It was in this era that Huniak became a regular, dropping by after his shift at a printing press. In 1997, when he heard Dietle’s was threatened with closure, he decided to buy the joint. “It was a sentimental thing,” he says. “I didn’t want to see it close down.”

His business strategy was simple: Keep Dietle’s the same. Not for him the fatal mistake of the guy who tried to upgrade the Twinbrook Tap Room, a neighborhood dive, by changing the name to Player’s Club, among other tweaks, losing his regulars and going out of business.

In fact, in two decades since Huniak took over, the only notable change he implemented has proven popular with loyal customers and newcomers alike. On most Saturday nights for the last few years, Dietle’s has featured live music, mostly rockabilly and blues and roots bands like the Nighthawks.

The sole major renovations came after the smoking ban took effect. Outdoors, where the front porch remains a popular hangout, Huniak made a small change that allowed customers to smoke while having a beer: All it took was the installation of a three-foot-high handrail that encloses the porch and legally renders it part of the premises yet skirts the indoor smoking ban.

Inside, meanwhile, Huniak used the ban as an opportunity to get rid of a century’s worth of damage from chain-smoking that had blackened the walls, floors, and woodwork. It took months. “There were layers and layers of this black goop,” he says. “As you scraped, you would hit another layer. You could literally see the years go by with every layer oozing off.”

Bug Man Pete has been working at a local pest-control company since 1988, specializing in termites.

It was during this time he says he “gravitated” to Dietle’s. He grew up nearby, and for years he had driven by and thought it was some old house on the highway. Now he counts on his favorite bar. It’s where they know his name—regulars call him Bug Man Pete, or just Bug Man—and what he likes and doesn’t like (“One thing I cannot abide is lite beer”) and where he knows he’ll always be welcome.

In fact, it’s quite a feat, it seems, to get yourself kicked out of Dietle’s. Even the hotheaded NRC-retiree provocateur comes regularly to deliver his German-expletive-laced outbursts in the free-speech bastion known as the porch. He’s been coming here since the ’80s, he explains—with no trace of irony—for the “relaxation and conversation and camaraderie” that he says he can’t find anywhere else.

At any rate, Pete says he wouldn’t want a place that walled itself off from characters like the guy on the porch right now, the one who looks up at a plane with a plume of white trail smoke flying overhead in the Rockville sky and solemnly intones, “They’re spraying us again.”

Can a shiny new pedestrian-friendly town center and an old drive-by roadhouse make nice as neighbors in the heart of one of MoCo’s hottest commercial zones? A century of history suggests the answer is yes. Not that Dietle’s patrons will necessarily appreciate what they see across the street. “Some people like change and some people don’t, and I’m one of those people who don’t,” Bug Man Pete says. “I accept it and I deal with it but, for the most part I want the same shit.”

Contributing editor Eddie Dean can be reached at eddiejdean@hotmail.com.

This article appears in the January 2016 issue of Washingtonian.