Local director Laura Waters Hinson is emphatic: this film about faith is not a faith-based film. “One of the worst headlines I’ve seen is ‘Michelle Dockery in faith-based documentary’ and I just wanted to die. That limits our reach. It’s a story about a unique, woman artist nobody’s ever heard of.”

That woman is the 19th century watercolorist Lilias Trotter and, unless you were one of the 704 who attended this week’s National Gallery of Art screening (seating capacity: 500), Hinson’s probably right. You have never heard of her. If it wasn’t for the work of her indefatigable biographer, 71-year-old Miriam Rockness, Hinson wouldn’t have either.

“One day, I got an email saying a board had been put together to make a short, educational film, and would I be interested in submitting a proposal?”

Two years later, Many Beautiful Things, which does star Downton Abbey’s Michelle Dockery, as well as John Rhys-Davies (Lord of the Rings’ Gimli) as the famous art critic John Ruskin, is making its debut.

The subject of the film is not the usual fare of art documentaries. Trotter didn’t find fame in life or after it. Her 75 years–the first half spent in England and dedicated to painting, the second half spent in Algiers and dedicated to missionary work–supply the film’s timeline. But it’s Miriam Rockness and her stubborn pursuit to see Trotter remembered that lends the film its heart.

There’s not a huge visual record for Hinson to work with here. Surviving paintings and journals inspired the script, but the most emotionally resonant moment of the film comes when Ruskin’s letters to Trotter materialize out of the depths of the Ransom Center (apparently the University of Texas had purchased them 50 years earlier and never knew what it had).

There’s not a huge visual record for Hinson to work with here. Surviving paintings and journals inspired the script, but the most emotionally resonant moment of the film comes when Ruskin’s letters to Trotter materialize out of the depths of the Ransom Center (apparently the University of Texas had purchased them 50 years earlier and never knew what it had).

The women who have been “obsessed” with piecing together Trotter’s story, including Rockness, sit around the kitchen table, reading aloud to each other. Someone remarks that Ruskin sounds like “a cross between a rejected lover and an Italian mother,” and everyone laughs. The question of whether Ruskin pursued Trotter romantically is an open one; the present-day story, driven by the curiosity and humor of these women, is where the audience’s concern lies.

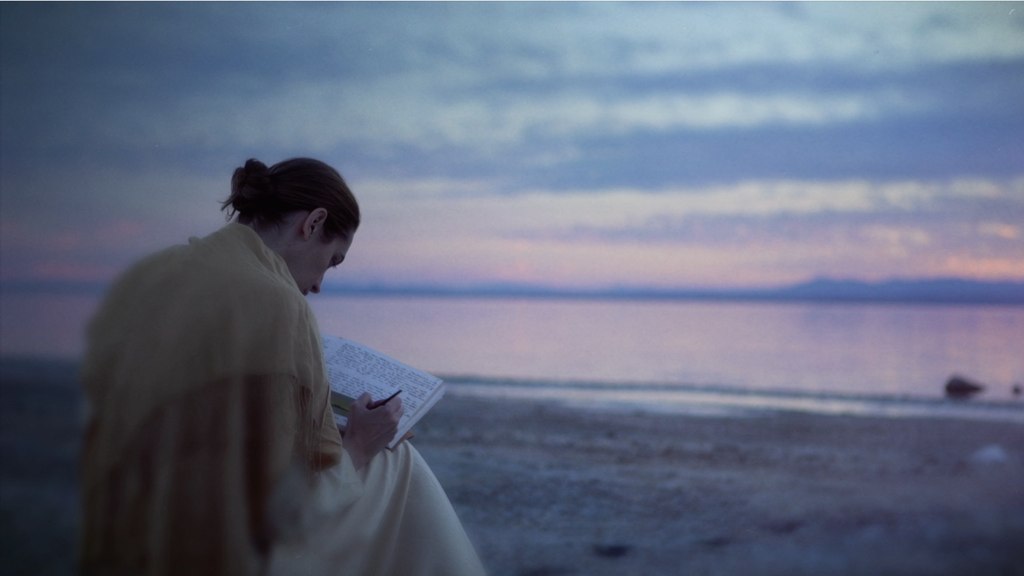

Hinson’s spare, ethereal film, told in watercolors that animate, silent reenactments, actor voiceovers and interviews with experts, is unfailingly earnest and respectful. That most of Trotter’s big life decisions are motivated by religion is clear. For a so-called faith-based film, though, those motivations aren’t ever endorsed. There’s no proselytizing here, and Trotter’s often-lonely life in Algeria isn’t glamorized.

In fact, her choice to take a self-funded mission to a country whose language she couldn’t speak still felt eccentric, at least to this modern viewer. It’s Rockness’ affection for the painter that humanizes her.

If anything, the lesson director Hinson took from Trotter’s story was decidedly secular. “It’s an adventure story. I think our culture can totally identify with the follow-your-heart ethos. And I think Lilias really embodies that idea, even at the risk of being judged.”

For a list of screenings, visit manybeautifulthings.com. It will be available for download on March 8.