The new Memory Lab at DC’s flagship Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial Library doesn’t come equipped with a box of tissues, but you may want to bring one in case. “This is the only space where we might regularly see people crying,” says digital curation librarian Lauren Algee.

Strong emotional reactions are expected. At the Memory Lab, which opened last Monday, anyone with a DC Public Library card can digitize their personal archives for free. Previously inaccessible VHS tapes, floppy discs, audio cassettes, and photo negatives can now be viewed on a computer screen and shared on a thumb drive, giving new life to things that seemed lost to time and changing technologies.

“People take for granted that whatever is happening now will always be,” says Jamie Mears, the archivist behind the construction of the lab. “It’s not until you use a VCR that you haven’t seen for ten years first hand that the threat of obsolescence to personal archives really sinks in.”

The obsolescence concept is what first inspired the Memory Lab—the newest addition to the Library’s Digital Commons section, which gives visitors access to expensive equipment like three-dimensional printers and on-demand book-printing free of charge. About eight months ago, Algee hired Mears through a Library of Congress residency program for post-graduate archivists to make a nagging idea of her’s come true: a workshop that provides people with an interactive experience on the proper way to archive their lives.

“When you are forced to use decks that no one has anymore to digitize something, you remember how quickly things fade, how quickly technologies pass,” Mears says. “It will help inform decisions that you make in the future about what you capture your home movies on.”

Absorbing this lesson comes naturally in the Memory Lab’s strictly do-it-yourself environment. During their sessions—which are booked in three-hour blocks—visitors are directed to a DC Public Library website with comprehensive instructions how to process the types of media they’ve brought. Mears is around for questions and assistance, but other than that, users are left alone to scratch and sniff their way through working the lab’s refurbished entertainment decks and digitizing software.

Absorbing this lesson comes naturally in the Memory Lab’s strictly do-it-yourself environment. During their sessions—which are booked in three-hour blocks—visitors are directed to a DC Public Library website with comprehensive instructions how to process the types of media they’ve brought. Mears is around for questions and assistance, but other than that, users are left alone to scratch and sniff their way through working the lab’s refurbished entertainment decks and digitizing software.

There are drawbacks for people who don’t possess adequate computer skills, but having complete control over the process is integral to the experience. Mears says Memory Lab users need solitude and seclusion when digitizing, as viewing long-lost photos and videos can make for raw, emotional scenes that she doesn’t want to interrupt. To ensure complete isolation, Mears has even lined the lab’s clear, glass walls with pieces of old microfilm. “We’re trying to give people a lot of privacy,” she says. “I’m not standing beside people.”

What happens once the digitization is finished is also out of the Library’s hands. Maryann James-Daley, manager of the library’s labs, hopes people will get creative with their files, such as one woman who turned her family’s grainy, 19th-century photographs into playing cards. There’s also discussion of using the lab to digitize footage for the library’s growing go-go archive, but that’s also dependent on what users offer to donate.

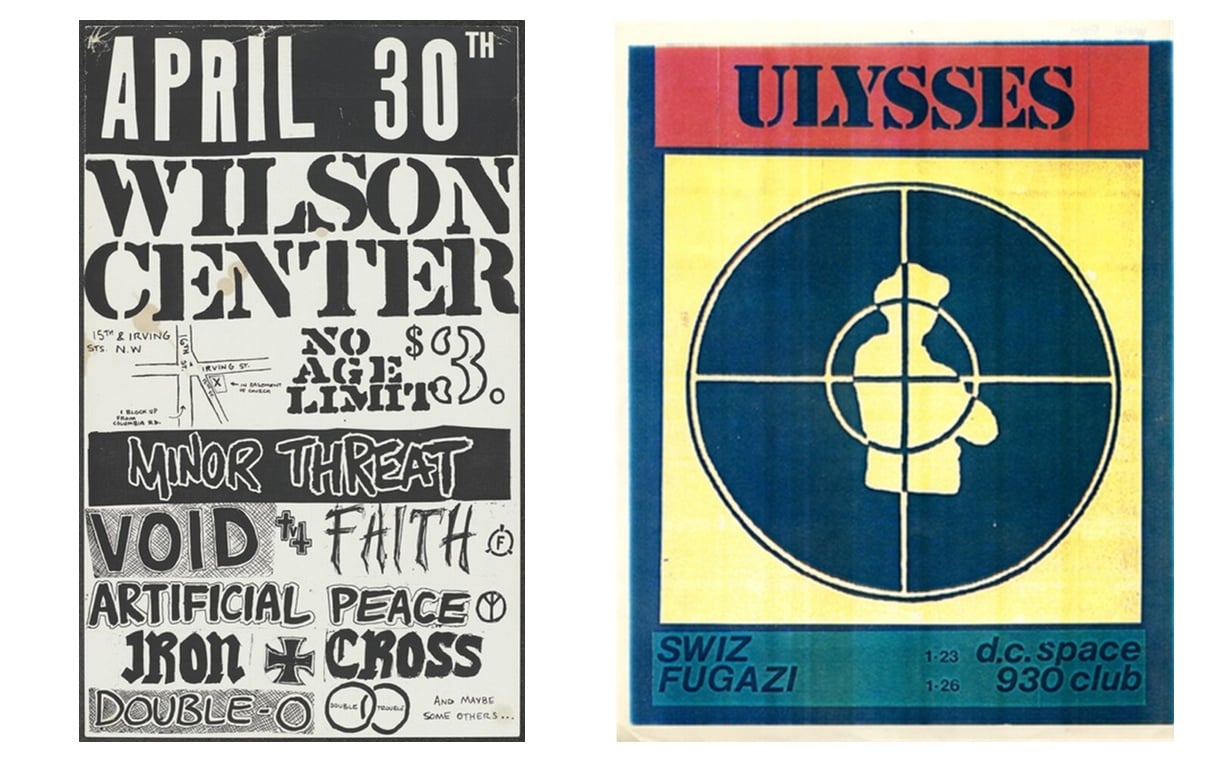

“When we did the Memory Lab opening,” Mears says, “we had a bunch of flyers that were like, ‘If you have go-go tapes that you recorded from the ’70s in DC and you digitized them, if you don’t mind giving us a copy, let us know.’ “

But even discounting the call for go-go tapes, the Memory Lab has been an immediate hit. Mears expected the rollout to be slow due to the lack of promotion, but already March is almost completely booked.

“[WRC] had a little segment on the launch that apparently played once,” Mears says. “And we had people walking in off the street with VHS tapes in plastic baggies saying, ‘I saw something on TV about this.'”