Crossing Over

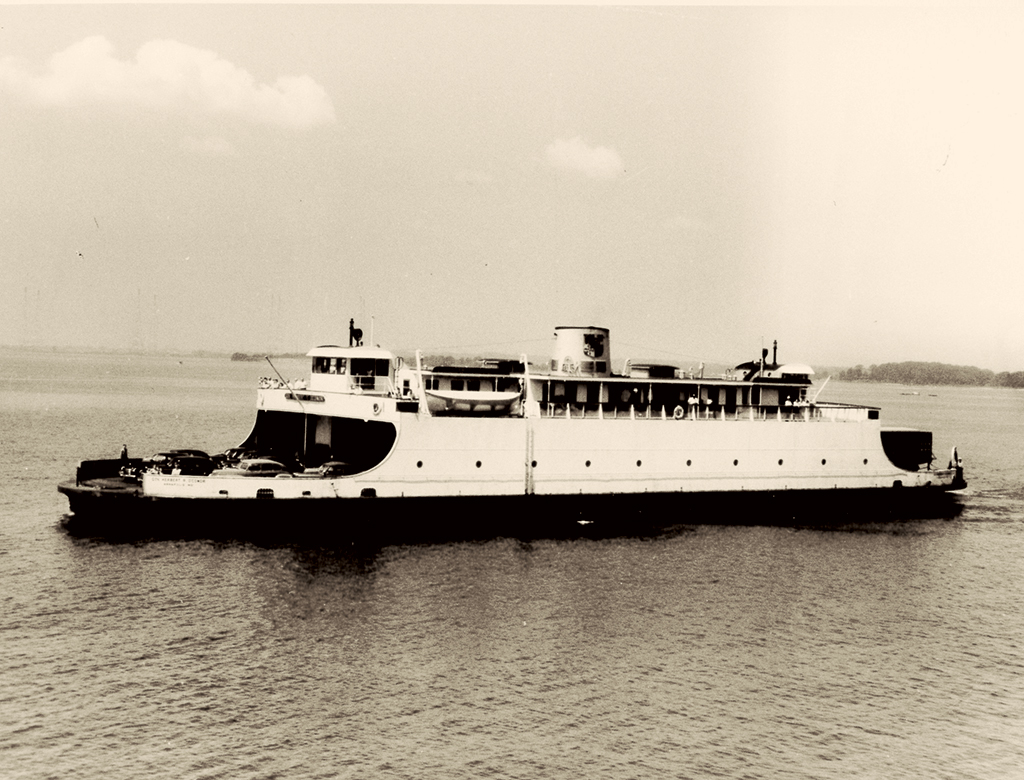

Before the Bay Bridge opened to motorists in 1952, car ferries were the fastest means to travel from the western to the eastern shore. But they weren’t always a pleasure cruise. The four-mile crossing between Annapolis and Matapeake, for instance, averaged 40 minutes, and on summer weekends, the line for automobiles to board often stretched more than three miles. Passenger ferries still run to Smith and Tangier islands daily, and in Talbot County the circa-1683 Oxford-Bellevue Ferry, the oldest privately operated ferry route in America, makes the scenic daily crossing of the Tred Avon River every 15 to 20 minutes from April through mid-November.

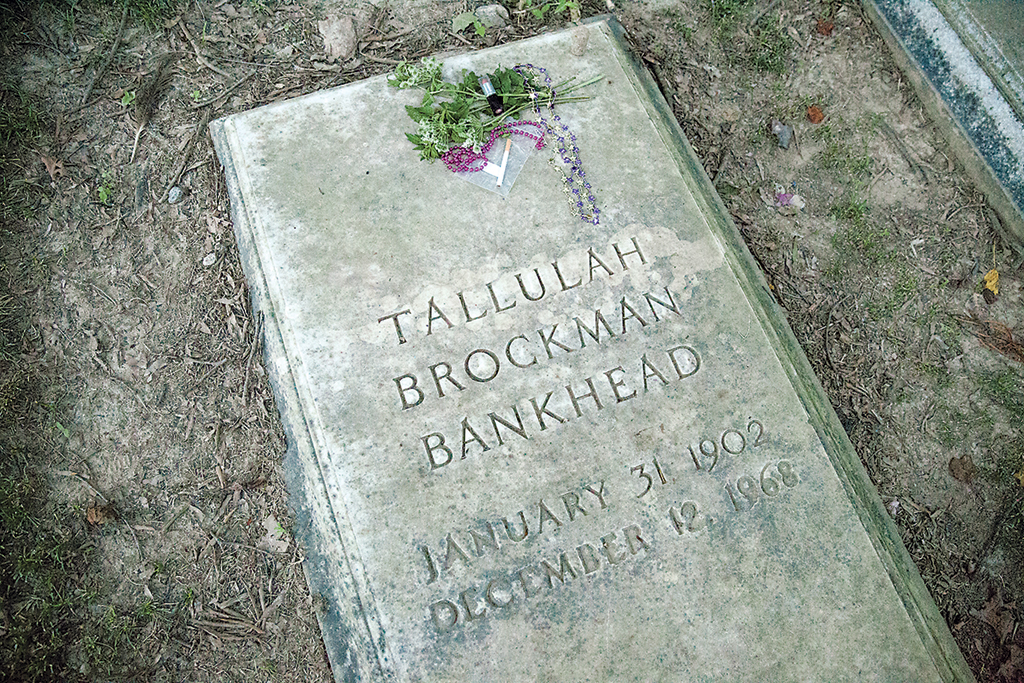

Rest in Peace, Dahling

Why would Hollywood actress Tallulah Bankhead be buried in a Kent County cemetery? Bankhead’s sister, Eugenia, lived near Rock Hall, and the movie star was a frequent visitor, often causing a commotion when the sisters went out on the town. After Tallulah passed away in Manhattan in 1968, Eugenia had her interred at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church near Chestertown so she could visit. Eugenia died in 1979 and rests in a grave beside her sister.

Sneaker Index

In 1988, former Maryland state congressman and environmental champion Bernie Fowler walked into the Patuxent River, in white sneakers, to gauge the river’s health by seeing how deep he could go before losing sight of his feet. (Water clarity is a distinguishing characteristic of a healthy waterway.) The result became known as the Bernie Fowler Sneaker Index. Fowler and his friends and family—last year, he was joined by Maryland congressman Steny Hoyer—have waded into the Patuxent every year since. Last year, at age 91, Fowler recorded 44.5 inches, the deepest level since 1997.

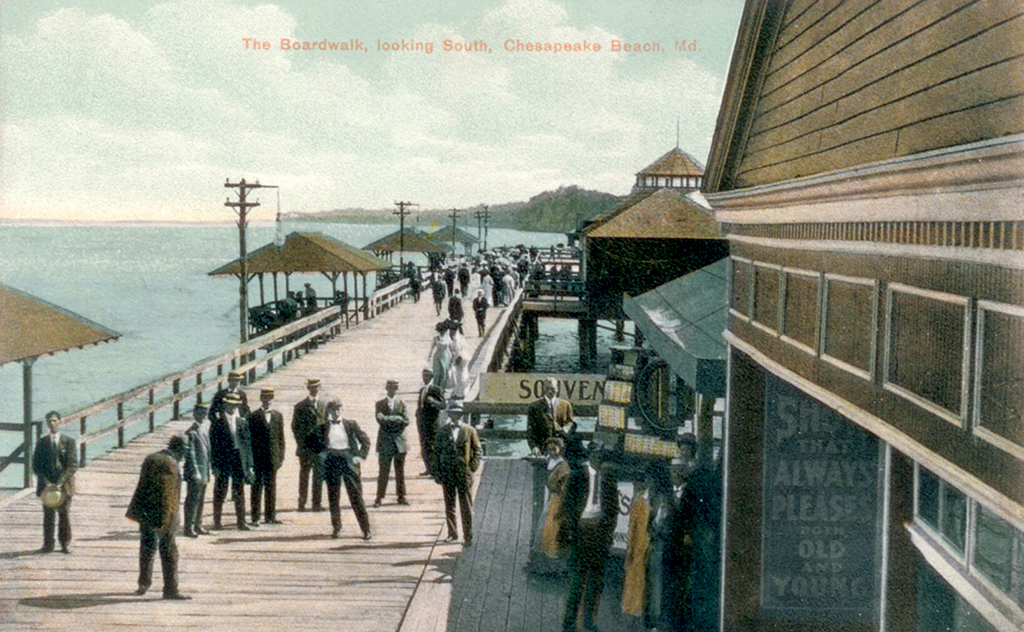

Lost Resorts of the Bay

From the 1800s through the mid–20th century, a getaway for many Washingtonians meant a trip to one of the resort areas along the Chesapeake or one of its tributaries. Among the largest was Chesapeake Beach, developed in the early 1900s in conjunction with a rail line that whisked vacationers 28 miles southeast from the District to the resort’s “healthful climate and saltwater breezes,” as an early advertising poster proclaimed.

Across the bay on the Eastern Shore at Tolchester Beach, just north of Rock Hall, steamships delivered passengers to a beachfront resort/amusement park. One of its strangest attractions was the carcass of a preserved whale: In its carpeted mouth, guests would sit at tables and have tea.

The resorts were segregated, so African-Americans established their own, among them Carr’s Beach and Highland Beach, which was founded by Frederick Douglass’s son Charles and daughter-in law Laura in 1893, after they were refused entry to neighboring Bay Ridge, now part of Annapolis.

With the completion of the Bay Bridge, Chesapeake resorts lost much of their appeal, as motorists were now within three hours of the Atlantic Ocean.

Annapolis’s Stop on the Chitlin Circuit

Carr’s Beach, near Annapolis where the Severn River meets the bay, was once the main Mid-Atlantic destination for African-American entertainers traveling the so-called chitlin circuit. Greats including Billie Holiday, Ray Charles, and James Brown played the venue between the 1930s and ’60s, but with the end of segregation, Carr’s diminished in popularity. Ironically, iconoclastic rocker Frank Zappa gave the final concert at Carr’s Beach—then known as the Great McGonigle’s Funky Seaside Park—in 1973. Today the land is the site of a condominium development.

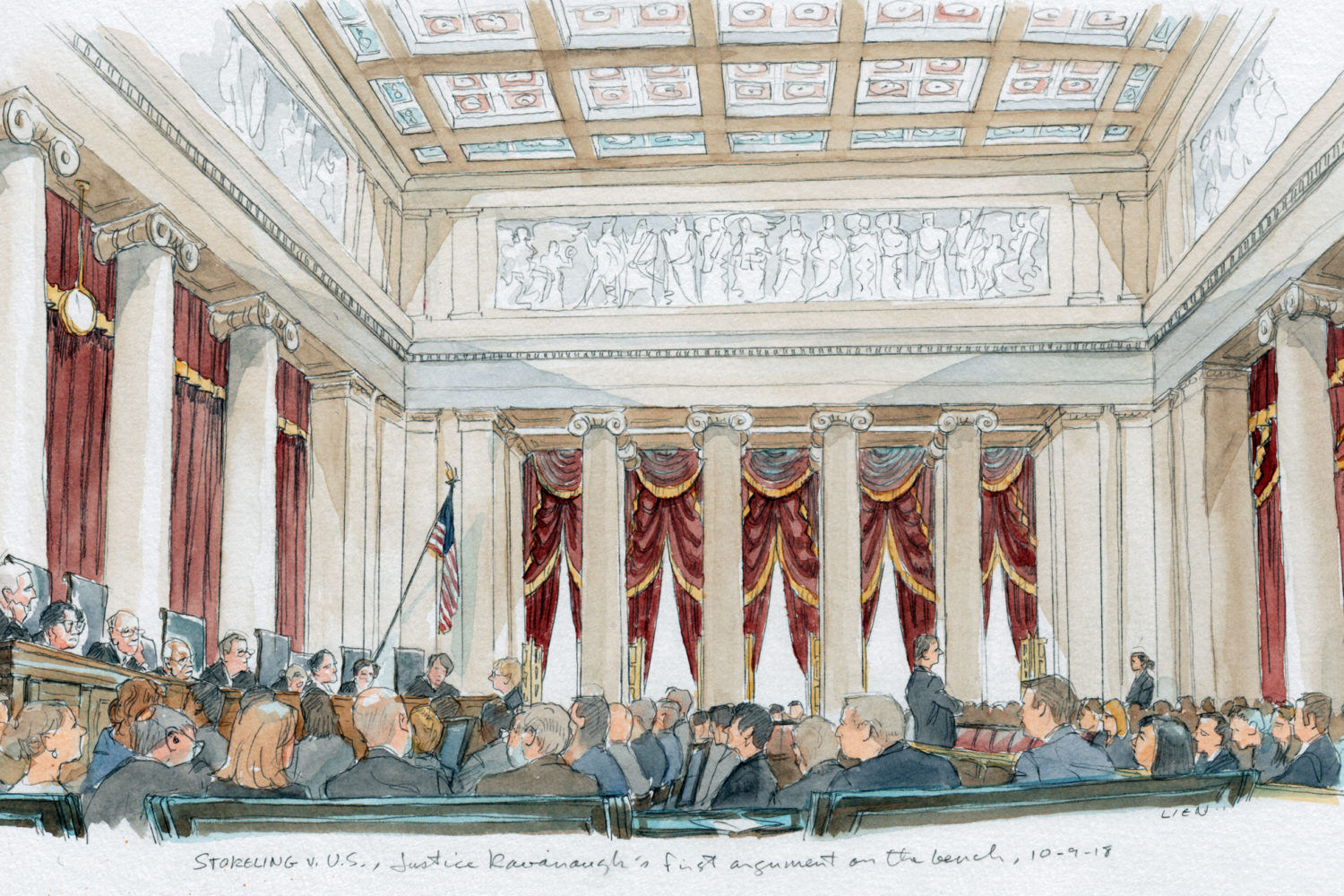

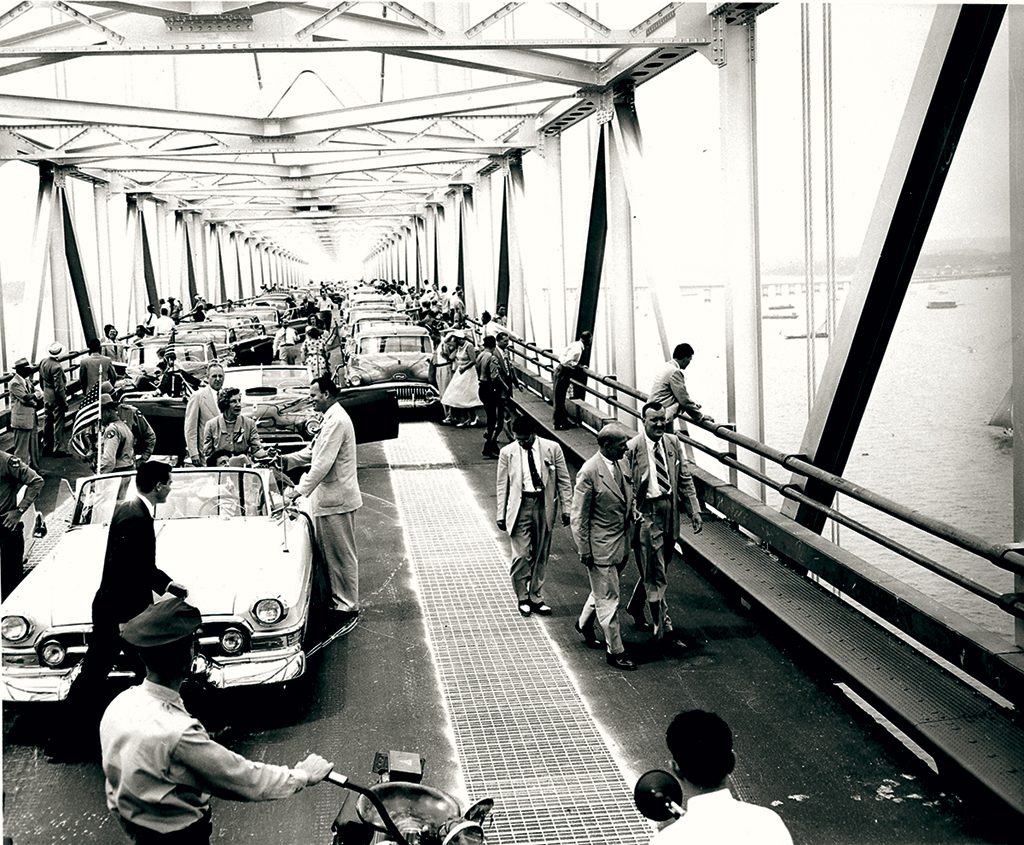

The Bay Bridge’s First Traffic Jam

In 1946, William Preston Lane campaigned for Maryland governor on a promise to get a bridge built between the western and eastern shores, an idea that had been brewing more than 40 years. His opponents dubbed the project “Lane’s Folly,” but he delivered, and construction started on what’s now the eastbound span in 1949. Three years later, Lane accompanied the new governor, Theodore McKeldin, in the first car to officially cross the bridge. Between all the celebrating and backslapping, the motorcade took more than two hours to traverse the 4.3-mile span.

Annie, Get Your Gun

When Annie Oakley and her husband, Frank Butler, decided to retire from their Wild West Show days in 1912, they built a house in Cambridge, Maryland, overlooking the Choptank River. Legend has it they designed a second-story landing where they could emerge from a bedroom and bag some waterfowl when the mood struck. After several years, the couple grew restless and moved on, but the house, a private residence, still stands at 28 Bellevue Road.

This article appears in our July 2016 issue of Washingtonian.