Davis Clayton Kiyo—high-school dropout, serial business owner, former weed dealer, current cannabis entrepreneur—is showing off his latest venture: a head shop that looks nothing like a head shop.

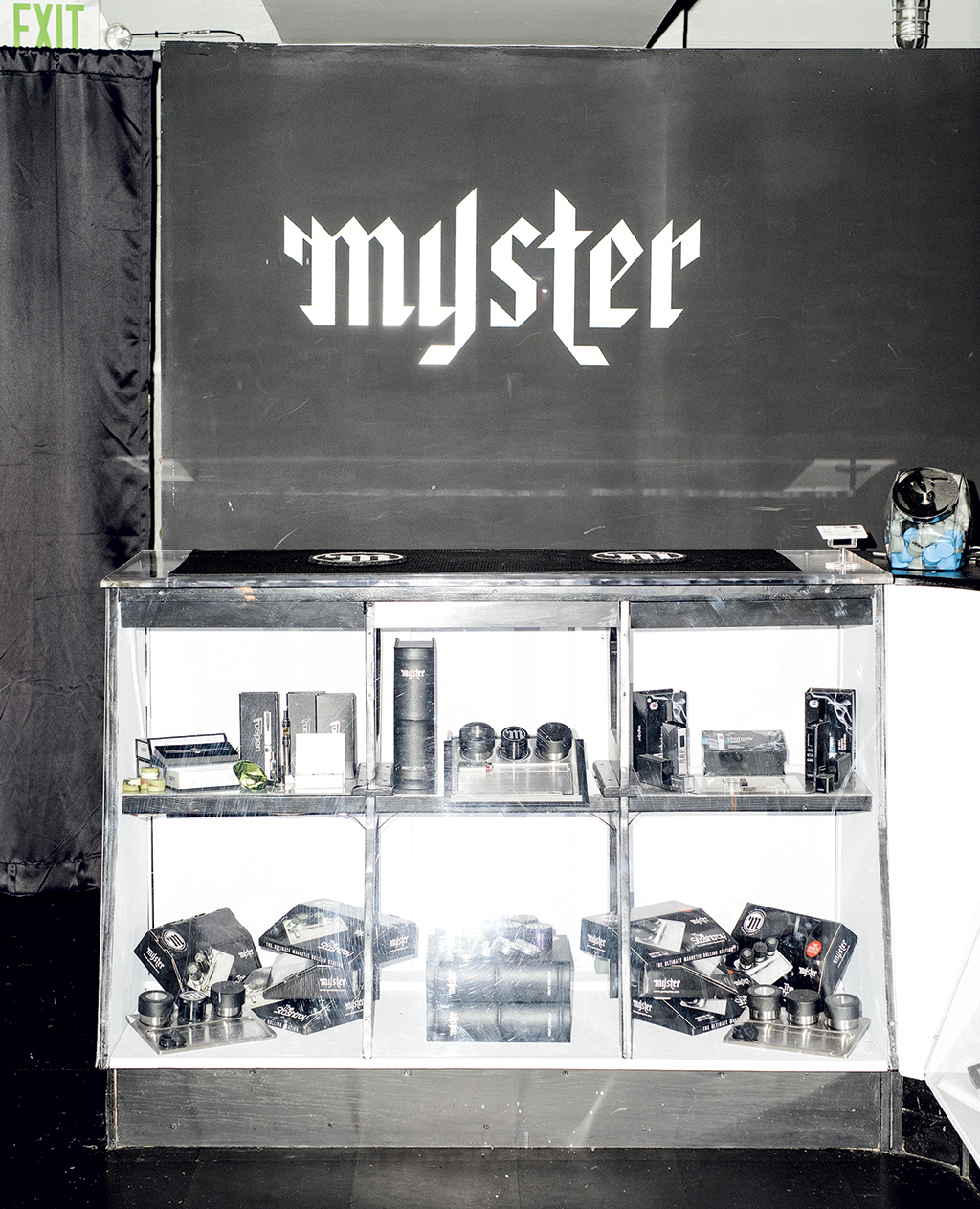

It’s minimalist and monochrome, lined with bright glass cabinets beneath a flat-screen TV that loops a slickly produced ad for his pot-paraphernalia product line.

The place is called the Fogden by Myster, “Myster” being the parent company under which Kiyo is seeking to redefine the marijuana enthusiast’s image for the more socially acceptable age of pot in which we now live—to alter it from smelly, dreadlocked hippie to, in his words, business-class, gainfully employed “successful stoner.”

Thus the shop’s sharp design and sleek products, which you could say recall an Apple store, or at least a place trying to recall an Apple store. It’s a comparison Kiyo doesn’t shy away from. “People love to say that,” he says, grinning. “I don’t say that. I wait for them to say that.”

This shop sits in Petworth, north of the buzziest part of Georgia Avenue, yet still in sight of luxury apartments and creeping gentrification. His other boutique is in a more surprising location: downtown Bethesda, in a high-traffic block of high-dollar restaurants and high-end shopping. Rather than encountering cliquish insiders deploying obscure pot jargon, visitors to the Fogden on Norfolk Avenue will find a staff of accessible devotees that again, yes, recalls an Apple store. Successful stoners welcome.

“I was very hesitant to open in Bethesda,” Kiyo says. His family moved to nearby Chevy Chase when he was nine, before he shortened his surname, Kiyonaga, to Kiyo, his “publicity name.” “But I was so surprised—everybody was happy to have us there. I’m trying to do this luxury thing, and people in Bethesda are into expensive shit.”

At 34, Kiyo is clean-cut, dressing against type in Louis Vuitton shoes, rarely without a flat-brimmed Nats cap. His basic business ambition is to be the point in the Venn diagram at which luxury tastes and marijuana tastes intersect. One of his favorite questions to ask is: How many weed-oriented companies can you name? It’s tougher than you’d think. Even aficionados struggle to say who made their favorite bong. Kiyo wants to turn his company into the answer. To make Myster—pronounced “my-ster,” with a bit of German inflection meant to convey an aura of sturdy engineering—into the household name in marijuana.

That people often call it “mister” doesn’t bother him too much: “You know, Louis Vuitton or Prada are weird names that are hard to pronounce. What’s important is to establish yourself as a brand, and it doesn’t matter if people don’t know how to say it.”

It all seemed to be going according to plan during my tour of both stores in early January. Kiyo was enjoying brisk retail and online sales, a write-up in Vice, but also one in the Washington Business Journal, and an Instagram following approaching 60,000.

A week later, though, it all was falling apart.

“Dude, the cops came in and busted the store,” Kiyo said in a frantic voicemail to me. It was a disaster: His business accounts were drained, more than $53,000 worth of inventory from his Bethesda store carted away.

“And it’s bullshit, completely. Call me when you get this.”

• • •

“Bethesda’s Bethesda,” Kiyo says when I reach him. “Maybe they got some calls from some parents or something. It feels a little bit like a witch-hunt.”

The day of the raid, he arrived to find Montgomery County police boxing up the contents of the shop, delicate glass craftsmanship cracking and shattering. The two Myster employees unlucky enough to be manning the store had been hauled in for questioning, and now it was Kiyo’s turn.

“Am I being arrested?” he asked an officer, in the kind of formal parlance a man experienced in police interactions might use.

No, the officer replied. Detained.

Kiyo had a lot to think about on the ride to the station. Washington is a warren of complex and sometimes contradictory laws about marijuana and its paraphernalia, gray areas that can change from block to block as you cross from the District into Maryland or Virginia. But when he emerged from questioning hours later, he still didn’t know why he was under investigation.

“You know why it’s such bullshit?” he fumes. “Because my store was really starting to pop off, and Maryland—there’s gonna be [medicinal] weed dispensaries soon in every district. Basically, when that happens, my store would’ve blown up and done so well.”

He would have to retrench, figure out some kind of comeback plan. “I really have this stubborn vision behind, like, creating the next Apple of this industry. And I think I can do it. I really think that I’m already on the way there.”

• • •

Kiyo was 12 years old the first time he smoked weed, but 13 the first time he got high.

It took like nine times, he says, smoking with his friends in Chevy Chase, pretending to be stoned. But then one day, it was like a “f—ing freight train.” He collapsed on the beanbag chair in his buddy’s basement. “I remember before I was falling asleep, I was just like, ‘This is it. I love this shit. This is what I f—ing love, already.’”

Love at ninth sight. Since then, barring a few grim months we’ll get to in a couple of paragraphs, Kiyo smoked every single day. At Bethesda–Chevy Chase High, he was “like, the weed dude.” He was popular. He sold grass to his friends. He was one class short of graduating.

His parents—father’s a local defense attorney, mother teaches kindergarten at a private school in DC—were not pleased. And that was before the feds came for him.

In the early aughts, Kiyo says, he was still dealing weed, getting it from some guys in Seattle. Didn’t really know where it came from before that, up the chain. Well, turns out it was from Canada. And the kid moving the product into the states got caught, big stash of money on hand.

The feds worked their way down the line, to the next one, and the next one, until they reached little old Davis Clayton Kiyonaga, the last link in the chain. By then it was 2004, a couple of years after he’d stopped dealing, he says. He was arrested on a federal conspiracy charge, released, and told to get himself to Montana, where the smuggling allegedly had originated.

He and his family spent a fortune on flights for various court proceedings, then got the case transferred to DC. Before the trial—those grim few months when Kiyo stopped getting high—the prosecutor, he says, told him there was a possibility of reducing his jail time: Plead guilty to the felony and he could avoid the maximum sentence. He was facing five years.

“We said no. F— it, we’re going to trial.”

The case nearly made it to jury selection before Kiyo’s gamble paid off. The government walked into court one day and dropped the case, the whole thing, just like that. No probation, no prison.

To hear Kiyo tell it, the judge was clearly on his side. “The lawyer from Montana got up,” Kiyo says, “and when he was talking, the judge was making faces like, This is the dumbest shit….It was just so clear that the judge was like not into this at all.”

Whether that’s true, court records don’t say. Point is, Kiyo left a free man. He celebrated by smoking weed again.

• • •

It seems strange, but before all that conspiracy stuff, Kiyo had never really thought hard about the politics of marijuana.

In high school, he’d go down to the Ellipse on the Fourth of July, when pot activists would stage smoke-outs: “It was just, like, a bunch of hippie people with BO. How are we ever gonna get weed legalized if these are the people trying to legalize it? Especially in DC, people really judge you on the way you look and the way you dress and what you drive and all this shit.”

Kiyo, who drives a shiny black Cadillac STS, hated that stereotype. Maybe if you could change the image, he started thinking, you could change the law. The seeds of Myster were planted.

He got a job at a photo lab—“I didn’t give a shit about the job, to be completely honest”—and was fired. He got another job at another photo lab. His new boss, Bill Lemer, was a serial entrepreneur, a big deal in town. He owned a MotoPhoto in Bethesda, the busiest one in the country.

I was like, ‘Look, man, I’m an entrepreneur. I’ve got money. I get shit done, this is my idea. What do you think?’

Kiyo still showed up late, still fell asleep in the back room. He was no good at being someone else’s employee, and Lemer decided to fire him. But Kiyo had a different idea. A few nights earlier, watching The 40-Year-Old Virgin, he’d wondered why nobody in Bethesda was running an eBay consignment shop like the one Steve Carell’s girlfriend operated in the movie. “I know how to work the internet really well,” he told his boss, and proposed a business venture. Amazingly, Lemer went along with it—loaned him $10,000 plus space in the corner of the MotoPhoto.

“There was something special about him, even though he messed up and made mistakes,” Lemer says. “I don’t know what it was—his personality, his salesmanship. It was just something that made me believe in him.”

This was 2006, 2007, just as the internet was about to finish the job of killing off photo labs—even the busiest MotoPhoto in America. Soon after Lemer closed up shop, he and his high-school-dropout business partner opened an eBay store in Bethesda together.

• • •

Kiyo is telling me his story in his Forest Hills apartment, which, like his store, displays the aesthetic of a style-focused minimalist.

He rents it out on Airbnb when he travels, and as if to advertise, Myster gear is all over the place. “You can smoke,” his listing says, “but you can’t smoke tobacco…#DCislegal.” The last couple who came through had already heard of Myster and indulged gratefully in the complimentary bag of weed he’d left for them.

But back to the story of before all that. Suddenly Kiyo is an entrepreneur, a businessman selling something other than eighths of weed to his friends. The eBay store lasts a handful of years before another pivot, this time to a shipping center, similar to a UPS Store. Again, brisk business.

Kiyo began to have high-profile clients. “Actually, like, a couple of famous, real-big-deal-in-DC clients where I was selling, like, huge amounts of stuff with them. So I really had to put on my professional face,” he says. In other words, “dress well, entertain clients, go on double dates and shit.”

It was on one of those double dates that his big idea came to him. Remember this name: the Stashtray.

The couple was a day trader and a lawyer, and Kiyo had been selling their high-end watches for them—$18,000, $20,000 timepieces. After a not-insignificant number of drinks at Persimmon together, the subject of weed came up. Counter to expectations, the rich couple acknowledged they smoked. So Kiyo invited them over after dinner to do just that.

“And like, I’m trying to impress this guy and look good,” he says. “I ended up taking out a shoebox, and there was a baggie in it. I couldn’t find my grinder, and it was just, like, an ordeal. Then I, like, started rolling, and didn’t have another part and had to go back. It was just, like, not cool.”

As origin stories go, this is no Edison’s light bulb. But it seems fated nonetheless. That junky shoebox full of weed may have suited the kind of guy who gets baked at the Ellipse on the Fourth of July, but not the one who sells an $18,000 watch to trade up for something better.

What could a smoker like him use?

• • •

A line is forming down the block of Myster’s Petworth location one bracingly cold day in late February. A banner waves: #freemyster.

In a precarious business position because of the Bethesda raid, Kiyo is throwing a “seed giveaway.” Under DC law, he can give away cannabis seeds to anyone over 21.

“What do we do with people smoking outside?” a staffer asks Kiyo, aware that toking in public is still illegal.

He thinks it over. “Just no bongs. Tell ’em to go around the corner if you see it.”

As the event begins, Kiyo walks the line of would-be botanists, shaking hands and briefing everyone on the situation in Bethesda, how they’re hoping to recoup their losses. The free seeds are in the far back of the store. To get at them, you have to snake past a gauntlet of salespeople enthusiastically promoting all manner of Myster wares. Including the Stashtray.

Recall, if you will, the double date, the stoner’s shame, and the idea that came to Kiyo afterward: a chic alternative to the shoebox.

“It was just a very vague idea,” he says. “But I would get high and talk about it all the time.”

He mentioned it to his sister and her then fiancé, who recalled an old roommate who worked as a product engineer at Oxo. They chatted on Skype, Kiyo outlining this strange concept of his. “I was like, ‘Look, man, I’m an entrepreneur. I’ve got money. I get shit done, this is my idea. What do you think?’ ”

The Oxo designer loved it. He wanted to build it and had contacts with Chinese factories that could mass-produce it. A year and a half passed. Six prototypes came and went, $250,000 worth of R&D. Kiyo funded it with his savings and the profits from an earlier invention—the Fogpen, a tiny cannabis vaporizor disguised as a high-end pen that any successful stoner can slip into a suit pocket after a surreptitious hit.

Finally, after a round of online crowd-funding in 2013, during which word of Kiyo’s exploits ricocheted all over the weed-web, he raised the last $42,000 he needed (and an extra $12,000 to boot). “I really feel like I can see the future,” he tells me. “Like I know what’s gonna be cool before it’s gonna be cool. I especially, like, know in this industry what’s cool.”

The Stashtray is Myster’s hallmark product, a stainless-steel, magnetized surface—an all-in-one receptacle for any paraphernalia you need to pack a bowl or roll a joint. But the true marketing coup is the Stashtray’s suite of “sold separately” add-ons—think magnetized lighter sleeves and grinders that make it more functional through customization. Buy one and you’re embedded in the ecosystem, ready to buy the next.

You probably don’t need me to underline the similarities here to a certain Cupertino-based tech company.

Also like that company’s lustrous gadgets, the Stashtray has a clean silhouette and looks good on a coffee table. “It’s a liquor cabinet for your weed,” Kiyo likes to say. It’s everything Myster represents, all for $99 plus shipping and handling. That is, unless you buy in-store.

That is, if by the end of this story Kiyo still even has a store.

• • •

In December 2015, an undercover detective in Montgomery County walked into Kiyo’s Bethesda shop and bought $140 worth of a translucent brown liquid called CBD oil.

In Kiyo’s telling, CBD—short for cannabidiol—is a completely legal chemical extracted from hemp that people call the “medicinal” side of the plant. You inhale it through a vaporizer like Myster’s Fogpen, and although it can’t get you high, believers swear it has such therapeutic effects as alleviating headaches, nausea, insomnia, seizures, and more. “I know it sounds like snake oil,” Kiyo says, but speaking of its properties like a mystic.

When he tells me all this, Kiyo is unaware that his CBD customer base included the police. He’s also apparently unaware that, back at the lab, the stuff tested positive for THC, marijuana’s psychoactive compound.

Then came the raid, the draining of Myster’s funds, and Kiyo’s long limbo.

After almost three months, on April 7, he was charged with three felonies related to the CBD oil—possession with intent to distribute a controlled dangerous substance, conspiracy to distribute a controlled dangerous substance, and a common nuisance law. Each carries a penalty of five years in jail or a fine of $15,000 or both.

The state of Maryland’s position is fairly simple: THC is a controlled substance, and Kiyo’s CBD products contained it—even if it was just trace amounts.

Kiyo’s lawyer says his client wasn’t knowingly selling an illicit product—he was selling the oil openly under the impression that it was legal. CBD manufacturers cite a 2004 case involving hemp, in which the court ruled that products derived from parts of the cannabis plant containing only trace amounts of THC should not be banned. “It’s straight-up f—ing legal,” says Kiyo. “It’s completely legal CBD oil because it’s derived from USDA-certified organic hemp. And it’s legal to sell in all 50 states.”

He certainly isn’t the only one who thinks this is the case, and Myster is far from the only company that sells the oil. But the issue isn’t exactly clear-cut. An advocacy group in DC called the Marijuana Policy Project says in a paper that the 2004 court decision “never touched on or even mentioned CBD or other cannabinoids. The case could be instructive for litigation if pursued by makers of CBD products, but it does not carry direct legal significance.”

Montgomery County suggested that Kiyo could plead guilty to a misdemeanor and avoid jail time. When you’re looking at 15 years, it seems like a no-brainer.

But for Kiyo, a guilty plea means that his business in Bethesda would be finished. He’d never recover his $53,000 worth of merchandise or ever reopen in his prime location, the home of so many successful stoners. The loss might compromise the entire Myster brand, from the Petworth branch to the online store. It would be the end of a dream.

“F— it,” Kiyo told himself, just like in his last felony case. “We’re going to trial.”

• • •

It’s April 23, two weeks after the charges were filed, and the air outside RFK Stadium is thick with the smell of weed for the first-ever National Cannabis Festival.

The place is packed with marijuana enthusiasts, activists, and vendors, alongside a lone police officer patrolling through the fumes in a fluorescent vest, looking resigned to the impossibility of his task of reminding people you still can’t smoke in public.

Despite its legal troubles, Myster has come out in full force. Its setup is closest to the stage, adorned with black leather seating where festival-goers are using gratis Stashtrays to construct combustibles. It’s by far the most bustling section of the entire festival, more populated than even the pizza truck.

At one point, a Myster employee gets on a loudspeaker and tells the crowd to get on their phones and text myster for a chance to win a raffle prize. To my bafflement, they do, passing off whatever smokable is in their hands and reaching for their phones. They must realize this is a marketing gimmick, that they’re handing over their personal data for a slim chance at a free grinder. Whether this is testament to the power of the Myster brand or just the power of free stuff, I don’t know. But the crowd keeps growing.

Amid it all is the kid once known as Davis Clayton Kiyonaga, smiling and shaking hands and probably stoned. He’s in deep managerial mode, coordinating the raffles and hawking merchandise and making sure no one hogs the recliner too long. He doesn’t look like a man facing three felonies, an existential threat dangling overhead like a guillotine. In fact, he tells me excitedly, there’s a rumor going around that Snoop Dogg was using a Stashtray during his surprise show at Echostage the night before.

“I hate saying this cause I sound so f—ing douchy, but, like, it’s getting to the point now where I’m getting recognized really often,” he told me earlier. “Like, when I flew from California back to here, like, a week ago, there was a beautiful girl who was, like, ‘Oh, you’re the Stashtray guy!’ ”

Kiyo’s trial is set for September. But right now, that faraway date in a cold courtroom doesn’t matter as much as today’s hot sun and the crowd lining up to be a part of the Myster brand, possibly for one last time.

Staff writer Michael J. Gaynor (@michael_gaynor on Twitter) can be reached at mgaynor@washingtonian.com.

This article appears in our August 2016 issue of Washingtonian.