By the time Terry McAuliffe, the governor of Virginia, finishes barraging me with talking points and factoids about education funding, highway-widening projects, the presidential campaign, and Twitter (“They don’t let me near it”), McAuliffe’s spokesman is looking anxious. We’ve blown past our allotted time, and the governor is expected at an event in five minutes.

“Before we wrap up,” the spokesman interjects, using the kind of verbal nudge toward the door familiar to PR pros everywhere, “would it be possible to offer just a sketch of where do we go from—”

McAuliffe suddenly bolts upright. “Have you seen the mansion yet?”

I have not.

He turns to the spokesman. “What do we got tonight, a Hispanic—what is tonight?”

“It’s the Asian American Heritage—”

“Yeah, well, c’mon over,” McAuliffe tells me. “Get yourself a drink, see the mansion.”

First, a detour. As the staff packs up for the day, McAuliffe leads me into the adjacent conference room. Inside is a blown-up state map and a photo of McAuliffe with a Middle Eastern crown prince. “I just got the poultry ban lifted in Kuwait and Oman,” he says. “First time ever. Big deal.”

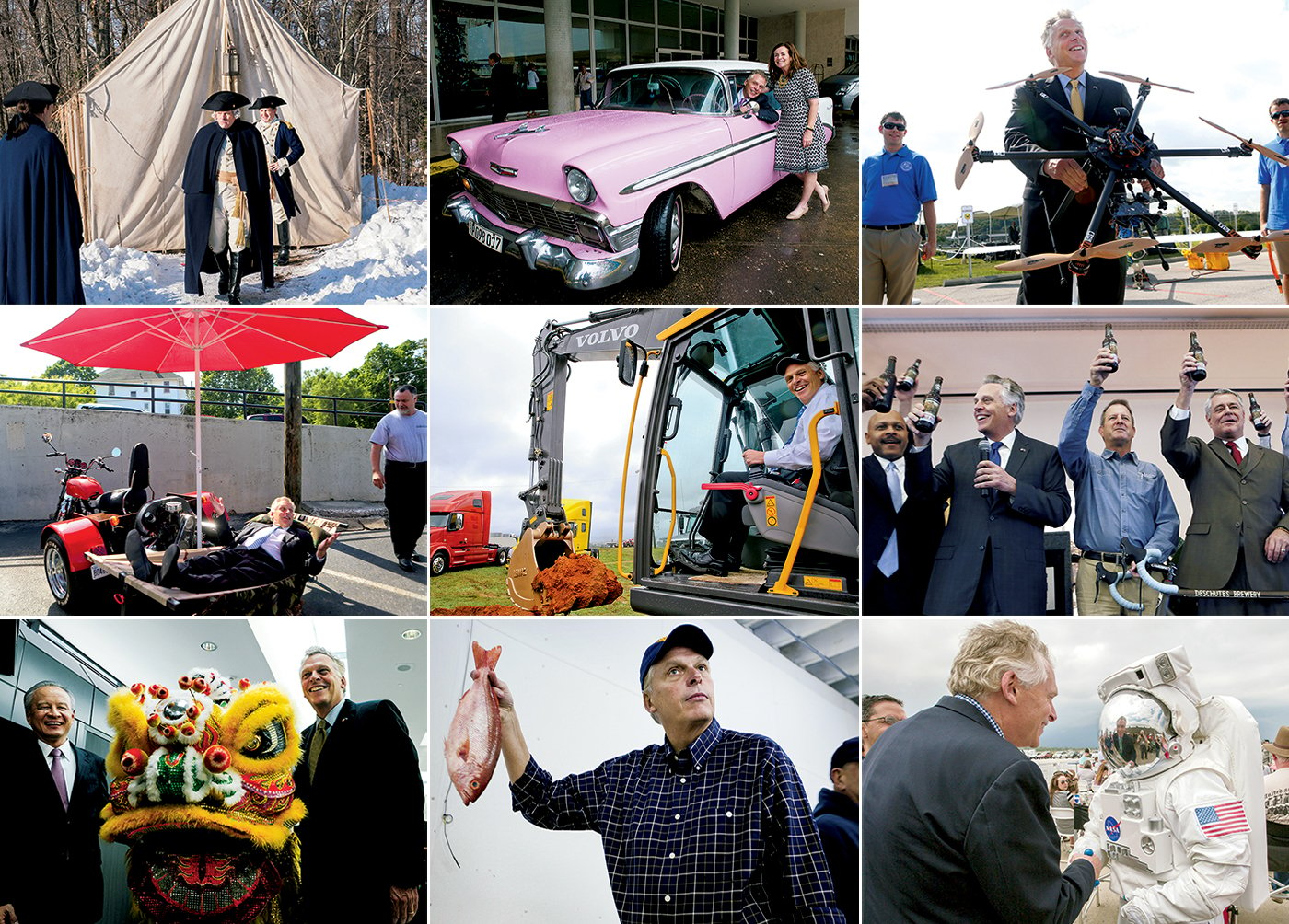

Spend any amount of time with the governor and you’ll get an earful about all the “firsts” and “mosts” and “greatests” he’s amassing before his four-year term ends. McAuliffe claims to be the first Virginia governor to visit all 23 community colleges and 36 state parks, the first to inspect the state’s two juvenile-justice facilities, and the first to drive the pace car at a NASCAR race. He’s the first Virginia governor to support same-sex marriage publicly—and to officiate at one. Virginia, he loves to say, is the “greatest state in the greatest nation on Earth.” Virginia farmers are the “greatest farmers in the greatest state in the greatest nation in the world.” The mayors of Norfolk and Newport News are, respectively, the “greatest mayor in America” and the “other greatest mayor in America.”

Washington is filled with people content to remain the Guy Behind the Guy. But not McAuliffe.

McAuliffe is 59 years old and six-foot-one, with big hands and a wide-shouldered build that brings to mind a retired tight end who now runs a local steakhouse. Yet he has the twitchy attention span of someone a generation younger. Confine him to the leather chair in his office, too small for his frame, and he’ll fidget and slouch, draping a leg over the side like an insolent teenager in pinstripes and wingtips.

In conversation, he combines the salesmanship of an infomercial host with the jargon of a corporate thought leader and the intensity of a high-school football coach on his third can of Monster Energy. He doesn’t get excited—he gets JACKED UP. He says, “ARE YOU KIDDING ME?” to underscore the magnitude of what he’s just said. He often abandons one line of thinking for another, mid-sentence, no warning.

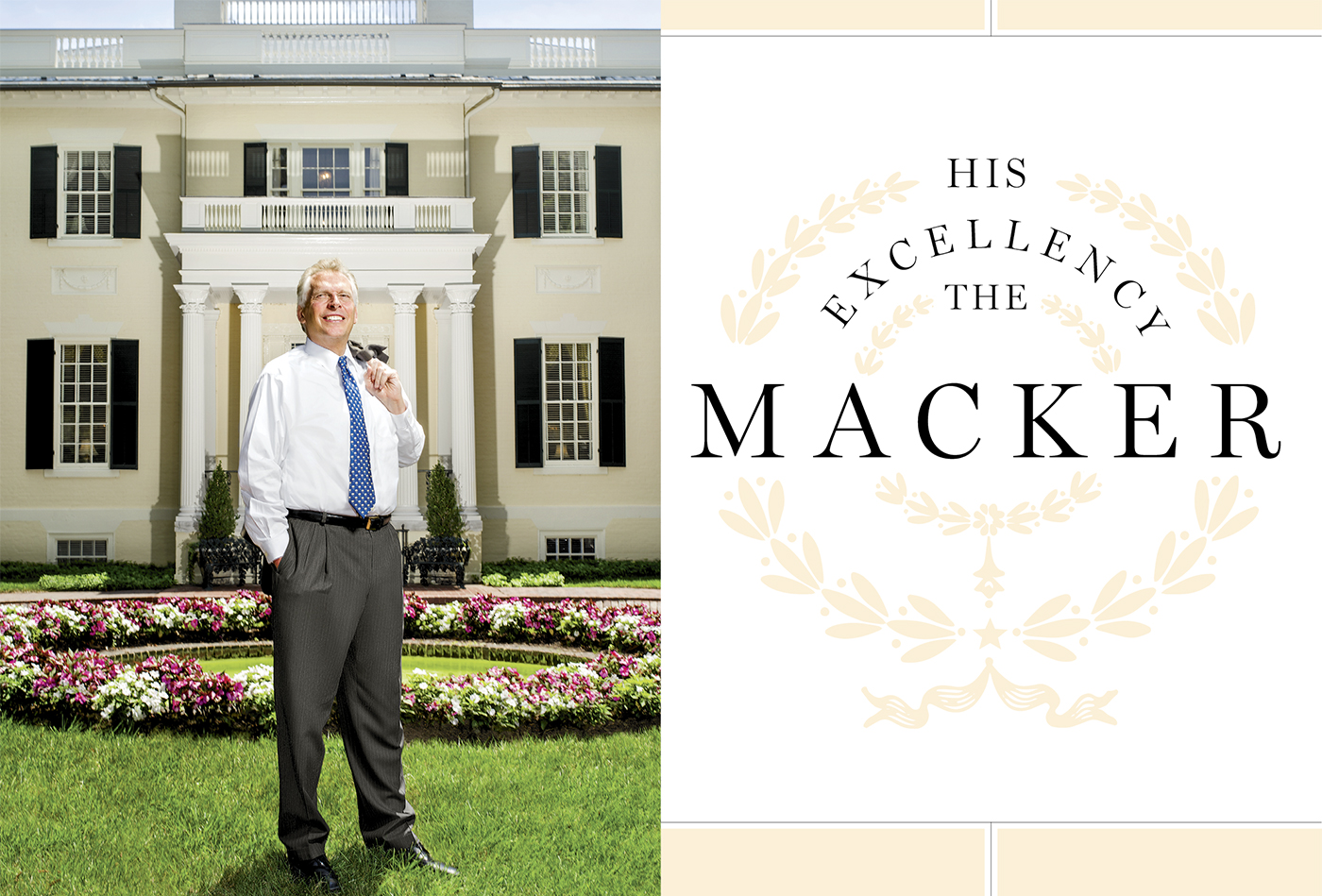

The 72nd occupant of the Commonwealth’s highest office, McAuliffe may be the most antic governor in the 240-year history of the position. He’s also one of the most improbable. Not long ago, America knew him as the Macker—the Clinton-family crony, the partisan warrior carrying the Democratic Party banner on the Sunday talk shows, the titanic political moneyman dubbed “the greatest fundraiser in the history of the universe” by Al Gore. But for the past 2½ years, he’s been in the actual business of governing, with its finance negotiations and its legislative skirmishes, and, especially, its opportunities to turn on the charm in public instead of in private. And, on this May afternoon in Richmond, he wants me to know it.

Informed that his guests are waiting, McAuliffe fetches his jacket and marches into the hallway. “C’MON, EVERYBODY,” he says. “LET’S GO.”

At the end of the hallway, we squeeze into his private lift. “Of course, you get your own elevator as governor,” he tells me.

As the doors close, he introduces his security detail, Scott and Dana of the Virginia State Police.

“Dana’s single,” McAuliffe says.

“I may not be,” Dana says. “Who knows?”

“Well, you’re not down the aisle, let me put it that way.”

The elevator beeps once, twice.

McAuliffe, again: “Scott’s single.”

“Not really,” Scott says, a touch offended.

“You’re not down the aisle.”

It’s only a slight exaggeration to say McAuliffe has gotten more mileage out of the official residence than probably the previous 71 governors combined. He invites lawmakers over for drinks during the legislative session, hosts receptions for constituents, and dines with foreign dignitaries and business executives. Oil paintings and historic artifacts abound, but the crowds flock to the mansion bar, which is stocked with Glenfiddich, Woodford Reserve, and other high-end spirits, all paid for by the Irish Catholic governor himself. Next to the bar sits a Kegerator that pours Virginia craft beer most days of the year. (On St. Patrick’s Day, it’s Guinness.)

“HIYA, EVERYONE,” McAuliffe says as he enters the house.

The First Family keeps its home in McLean but mostly lives in an apartment on the mansion’s second floor. It’s not uncommon to see one of the McAuliffe kids in gym shorts and sandals weaving through the guests to snag a crabcake phyllo cup. “It really reminds me of my fraternity house,” a staffer in the administration says. “Everybody lived upstairs, but this is the party floor.”

On this occasion, McAuliffe is celebrating Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month in Virginia. “As you know,” he tells the audience, “I’m the first governor to host this event every single year.”

As his talk progresses, he points out staffers in the audience, says farewell to an aide leaving for a job in the White House, and praises his wife’s work fighting child hunger. “There’s a lot of history in this house,” he continues. Built in 1813, it’s the oldest, most continuously lived-in governor’s mansion in the nation, he explains.

“So when you go to bed tonight, think about that: Patrick Henry, our first governor. Thomas Jefferson, our second governor. And now,” he says, rearing back, lifting both arms in the air, and flashing that money grin, “Terry McAuliffe.”

• • •

A week later, I’m riding with McAuliffe in a black Suburban as a police escort parts the early-afternoon traffic on I-66. Over the whine of sirens, his spokesman reads aloud a just-issued press release. It’s breaking news out of the governor of the Commonwealth’s office: Ballast Point, a craft brewery in San Diego, will invest $48 million in a new facility near Roanoke.

McAuliffe has heavily courted the craft-beer industry. The Kegerator in the mansion? He had it installed in 2014 to win over executives of California’s Stone Brewing Company, the tenth-largest craft brewer in the country. (It worked.)

Now the governor looks up from his briefing book to tell me that the brewery is making him his own beer at its Richmond location. He picked out the ingredients just the other day.

“What kind of beer?” I ask.

“I’m not really supposed to tell ya,” he says. Before I can push him for more details, he blurts out, “Stout. Very bold.”

This beer have a name?

McAuliffe’s eyes get wide. “Your Excellency.”

It’s a nod to His Excellency, an honorific given to Virginia’s governor, which supposedly dates to the Colonial era.

His Excellency Terry McAuliffe. Let that sink in.

• • •

When I think of Terry McAuliffe, the tape in my head rewinds to June 2, 2008. McAuliffe was chair of Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign, and he appeared that day on MSNBC’s Morning Joe to discuss her victory in the Puerto Rico primary. Instead of his usual suit and tie, he wore a yellow-green Hawaiian shirt, described by one reporter as the “most hideous shirt ever made,” and brandished a bottle of Bacardi.

Puerto Rico was one of the last primaries that year—Barack Obama had all but locked up the nomination. Yet McAuliffe, playfully defiant, refused to concede. He fired off talking point after talking point and vowed to bring that Bacardi bottle to the set later that week to “celebrate Hillary, the nominee of the Democratic Party.”

The performance was vintage McAuliffe. There he was on national television, the shameless hack, declaring that Clinton could prevail long after the math had shown otherwise; the court jester using every gag, trick, and prop in service to his famous friends; and of course, the Macker, a bottomless well of energy in the face of insurmountable odds.

McAuliffe has always been best known as the “First Friend” and rainmaker to the Clintons. He helped devise Bill’s shock-and-awe 1996 fundraising blitz, including those infamous Lincoln Bedroom sleepovers. He rescued the 2000 Democratic convention in Los Angeles, erased $18 million of debt at the party’s national committee, and raised hundreds of millions of dollars for the family’s foundation and for Hillary’s 2000 Senate and 2008 presidential runs. All the while, McAuliffe was the President’s late-night cards buddy, his golf partner, his pick-me-up.

“Every time I was down in my life when I was President,” reads an epigraph by Bill Clinton in McAuliffe’s 2007 memoir, What a Party! My Life Among Democrats: Presidents, Candidates, Donors, Activists, Alligators, and Other Wild Animals, “every single time, Terry was always there.”

Washington is filled with people content to remain the Guy Behind the Guy. But not McAuliffe. As Hillary’s 2008 campaign wound down, he decided it was his turn. “For 20 years, I’ve raised all this money to help people win, people that I believe could grow the economy and create a socially just society,” Bill Clinton says McAuliffe told him. Now he wanted to be the one in charge.

To some, it was pure comedy that the hack in the Hawaiian shirt thought he could become the wonk. “Terry McAuliffe for governor?” scoffed the Richmond Times-Dispatch editorial page. “We had assumed the third of the Clinton triplets lived in Chappaqua,” the paper wrote, referring to the Clintons’ New York home (which McAuliffe had offered to secure with $1.35 million of his own cash).

Even friends were surprised. “He was never the one that you always thought would run,” says former Bill Clinton adviser Paul Begala, who has known and worked with McAuliffe for 30 years.

In January 2009, McAuliffe entered a three-way Democratic primary. He ran as an Obama-style Democrat preaching the gospel of renewable energy and gave out copies of What a Party! to introduce himself to Virginians. To make up for his lack of experience, no stunt was too corny—he even brought a person dressed up as a diaper-wearing chicken to a campaign rally to champion the use of chicken droppings as biofuel. Try as he might, McAuliffe couldn’t shake the image of the DC insider skipping to the front of the line in a state famous for its parochial politics. He lost the nomination by 23 points.

McAuliffe, though, didn’t just crawl back to the life of an operative. For the next four years, he hosted fundraisers for state legislators, boned up on policy, and greased the local pols and pooh-bahs. When he ran again in 2013, this time without a primary opponent, his campaign had an almost myopic focus on a subject dear to Republicans: job creation. The GOP’s own candidate, by contrast, fit the textbook definition of a right-wing culture warrior, attorney general Ken Cuccinelli.

Aided by a state-of-the-art ground game and data operation run by Robby Mook—yes, the one who’s now Hillary Clinton’s campaign manager—McAuliffe snapped a 40-year streak of Virginians electing a governor from the opposite party of the sitting President. At his inauguration, even Bill Clinton couldn’t hide a smile when his good friend was introduced as His Excellency. “I kept wondering whether I should offer to get him one of those 18th-century wigs and have it powdered for him on a regular basis,” Clinton told me recently.

But here’s the real punchline: McAuliffe isn’t half bad at being governor.

In that same doggedly shameless way he had as a fundraiser—wrestling an alligator for a $15,000 check, calling astronaut and then-congressman Bill Nelson aboard the space shuttle Columbia before liftoff to collect on a commitment, and most famously, stopping at a fundraiser on the ride home from the hospital after the birth of his youngest son—McAuliffe will see anyone, go anywhere, and do anything to bring money into Virginia. He’s flown in fighter jets, ridden in a swamp boat, eaten exotic foods, and played a Revolutionary War general in an AMC drama. His Rolodex is one of the thickest in politics, a not-unhelpful asset for an avowedly pro-business New-Democrat-for-the-21st-century governor.

“I’m sure you’ve gone on the website,” he told me breathlessly soon after we first met, “but I just announced 4-percent unemployment . . . . 156,000 new jobs . . . . I inherited a $2.4-BILLION-dollar deficit . . . .We turned that into the largest surplus in Virginia history. . . . I just put a BILLION dollars into education, the SINGLE BIGGEST investment in Virginia history . . . . I put $50 million into the Dulles Airport . . . . We’ve done about $11.2 billion in new capital . . . . I have 30,000 jobs open right now . . . . 17,000 cyber . . . . 17 trade missions, doing my 18th tomorrow . . . . ”

It’s the kind of bragging many governors traffic in—if not with quite as much lung power as McAuliffe. Still, the leader of the Commonwealth, faced with hostile Republican majorities in both chambers of the General Assembly, has found some common ground and gotten a few things done.

Following the Democratic attorney general’s controversial declaration in late 2015 that Virginia would no longer recognize concealed-handgun permits from 25 other states, McAuliffe cut a deal: In exchange for reinstating those rights, Republicans and the gun lobby would allow voluntary background checks at gun shows and new restrictions on gun rights for domestic abusers. McAuliffe also negotiated a $100-billion biennium budget with the Republican-controlled legislature, a deal in which both parties declared victory.

Those are exceptions: For the most part, Richmond is mired in a kind of partisan gridlock that no amount of Mackerish glad-handing can break. So it’s unsurprising that as we made our way around the state this spring and summer, McAuliffe seemed keener to tout all the things he’d done unilaterally—his 130-odd vetoes and executive orders. “Literally, you can pick up a piece of paper and write down an executive order and you can change people’s lives,” he said.

At roughly the midpoint of his term, His Excellency was feeling excellent. His approval numbers hovered in the high 50s. He was showing other Democratic governors how to work with—or around—a hostile Republican legislature. Fellow governors from both parties would soon elect him chair of their national association.

“I’m as energized at 5 in the morning as I am at midnight. I’m on the go. I love life,” he told me. “This is the greatest job in the world.”

All the same, with a presidential election looming, the greatest job in the world was about to get trickier. Convincing the world that you’re no mere crony is hard enough in normal times. The task is considerably harder when you’re also trying to deliver your state to your national-politics patrons.

• • •

The way he tells it, the idea came to him one day last November. McAuliffe had read that Kentucky governor Steve Beshear, on one of his last days in office, had signed an executive order reinstating the voting rights of nonviolent ex-cons (excluding those who had committed sex crimes, bribery, or treason). Says McAuliffe: “I called my secretary of the Commonwealth and said, ‘If [Beshear] can do that down there, I wanna know if I can do it up here.’ ”

The reasoning, to McAuliffe, was simple: The state’s policy of denying felons the right to vote—a policy that has long had a disproportionate impact on African-Americans—was a blight on democracy. At the time McAuliffe signed his order, one in four African-Americans in Virginia was banned from voting. But legally and politically, it was more complicated.

McAuliffe’s predecessors believed the state constitution didn’t allow for such a blanket order. “I really wanted to do it, but I could not conclude that this was something I clearly had the power to do,” says vice-presidential nominee Tim Kaine, who was governor from 2006 to 2010.

Lawyers in the McAuliffe administration, by contrast, saw no problem. As his spokesman Brian Coy puts it, “There were previous governors who seem to have looked and may have been concocting reasons to maybe give themselves political cover for not acting.” McAuliffe assembled a small team of wonks to figure out how many people’s rights he could restore in one fell swoop. The group worked in secret for several months, then called for a press announcement on April 22, two days after the Republican-led legislature—which would have gone berserk had it gotten wind of such a proposal—adjourned.

That morning, “the greatest day of my life as governor,” McAuliffe stood outside the state capitol and restored the voting rights of 206,000 ex-cons—the largest mass clemency order of its kind in history. “Not long after President Abraham Lincoln celebrated emancipation with former slaves gathered not 20 yards from where I’m standing,” he said, “Virginia initiated a campaign of intimidation, of corruption, of violence aimed at separating African-Americans from their constitutional right to vote.” His order, he announced, was a step toward correcting Virginia’s “long and sad” history of racial disenfranchisement—a “historic” move, according to a New York Times editorial.

This is where being First Friend makes politics complicated. Republicans blasted the maneuver as nothing more than a political ploy. “The singular purpose of Terry McAuliffe’s governorship,” said Virginia House speaker William Howell, “is to elect Hillary Clinton President of the United States.”

I pressed McAuliffe on that point several times. C’mon, you’re Terry McAuliffe, I argued. It’s impossible not to see the executive order as doing a solid for your pal Hillary.

He conceded that a disproportionate number of ex-cons who benefit would probably vote Democratic, but he said his timing dispelled any political motives: “We have elections every year in Virginia. If I was gonna do it for political purposes, I would’ve done it last year when I tried to get one seat for the state Senate [majority] and I lost by 1,500 votes.”

Clinton, he assured me, would win Virginia with or without this measure—just as Obama had in 2008 and 2012.

Shortly after that conversation, however, you could see the situation beginning to unravel. First, the legislature’s Republican leaders and four voters filed suit, claiming the order was unconstitutional. Next came a steady drip of news stories highlighting errors in how McAuliffe’s administration had implemented the order—among other problems, a handful of violent felons still in prison or living in a different state had mistakenly gotten their voting rights restored.

I could see McAuliffe growing more frustrated as he fielded question after question about the rollout. On one visit to Richmond in late June, I overheard him grilling the state official who manages the list of eligible ex-cons about the embarrassing headlines. “There will be no more stories about mistakes in the list,” I heard her say. Two weeks later, the Richmond Times-Dispatch reported that the administration had mistakenly included two fugitive sex offenders on the list.

The worst news of all broke on July 22: Only three days after the state Supreme Court held a special session to hear arguments in the lawsuit challenging the executive order, its judges struck it down 4–3. McAuliffe lacked the authority to issue blanket clemency, they said—and just like that, his “historic” maneuver was undone.

Of course, the Commonwealth’s governor refuses to be outdone. In a feat of McAuliffian bravura, he has vowed to sign individual clemency papers for all remaining ex-cons before leaving office in January 2018. “Every single one of them,” he told me. “I’ve got all their names and addresses. These people are all getting their rights.”

On paper, the executive order was the perfect opportunity for McAuliffe both to burnish his policy cred and to deliver on the politics. But by bungling the measure entirely, McAuliffe only underscored just how new he still is to the job. Campaigning isn’t governing, and all the “greatests” and “firsts” in the world won’t change that.

• • •

“No one’s alleged any wrongdoing on my part” are eight words no politician ever hopes to say to a scrum of TV cameras. On May 24, it was McAuliffe saying them.

“Allegations happen,” he told the crowd of reporters grilling him outside an event in west Alexandria. “I don’t think it will affect me at all.”

The day before, CNN had revealed that the feds were investigating the governor for allegedly taking illegal campaign money from a Chinese businessman during his 2013 race. The sourcing was fuzzy (“US officials”) and the allegations confusing—the same story said the businessman had permanent US residency, which legally entitled him to write political checks. Nonetheless, the news resurrected all the old criticisms of McAuliffe as the seamy DC operative. “No wonder [McAuliffe] recently gave ex-felons the right to vote,” quipped Republican pollster Frank Luntz.

It’s a pretty good bet the intense media coverage that followed would not have attached itself to allegations against a governor of Oklahoma or Oregon. As McAuliffe took questions about the investigation and, of course, the Clintons—for whom the news was terribly timed—I stood a few feet away. McAuliffe had agreed to let me shadow him that day. Would His Excellency call off our arrangement now, in light of this most unexcellent leak?

Nope.

McAuliffe is no novice when it comes to federal investigations. But it’s different when you’re a sitting governor who wants nothing more than to be taken seriously as a public servant.

On the way out of the event, I watched as a local reporter and cameraman ambushed him on live TV. He looked flustered but offered his stock answer and climbed into the idling Suburban. “Why don’t these guys do their own research to find out if this guy is a legitimate donor?” he asked once we were in the car.

Over the course of the day, McAuliffe was hardly his sunny self. At lunch he did his best to deflect attention from his sudden turn of fortune, reminiscing about his upbringing in Syracuse, where his father was a fixture in the local Democratic Party and where the guv himself worked his first fundraiser at just six years old. For the most part, though, he was strangely quiet—not mopey but subdued. E-mails came in from friends urging him on (“Hang in there,” wrote Steve Elmendorf, the Democratic power lobbyist). Looking over his shoulder, I noticed him trading texts with his eldest son, Jack, who serves in the Marines. “In the arena,” Jack wrote. It was a reference to one of McAuliffe’s favorite quotes, the well-trod Teddy Roosevelt line about how credit belongs not to the naysayers but to the man “who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood . . . .”

Unlike the vast majority of politicians, McAuliffe is chronically early. If you ever want to meet the man one-on-one, pick an event on his calendar, find the nearest Starbucks, and show up 30 minutes before the event starts. That’s where we’re headed near Capitol Hill, an hour before his briefing to the Virginia congressional delegation, when the anchors on WTOP begin to read their report on the investigation into McAuliffe. For the first time all day, nobody talks, including the governor’s chatty security detail—the car is silent. It’s one of the stranger moments I’ve witnessed in the presence of a politician.

Over the next week, the story gets worse. After speaking with the Justice Department, McAuliffe’s lawyer says that investigators are in fact looking at whether McAuliffe, before he became governor, violated federal law by lobbying for a foreign government without properly registering as a lobbyist. In other words, the feds aren’t digging into one of his donors—they’re focused squarely on McAuliffe himself.

He denies that he broke any lobbying laws, saying, “I have never lobbied a day in my life.”

That hazy space at the nexus of business and politics is one McAuliffe has inhabited for much of his career, ever since he went into business with his future father-in-law after meeting him on Jimmy Carter’s 1980 campaign. Along the way, he’s been dogged by investigations and questions of impropriety. Before the Chinese-donor debacle, there was the controversy surrounding GreenTech, the electric-car company McAuliffe led before running for governor. In March of 2015, the Department of Homeland Security’s inspector general found that he had received “unprecedented” special treatment in obtaining visas for the company’s foreign investors.

But even if McAuliffe is no novice when it comes to tangling with the feds or being the subject of unflattering headlines, it’s one thing to do so when you’re just a private citizen—and another altogether when you’re a sitting governor who wants nothing more than to be taken seriously as a public servant.

“Nobody likes to see a headline like that and come out of nowhere like that,” his wife, Dorothy McAuliffe, tells me, chalking the leaks up to Republicans who want to damage her husband. “I can’t say that it doesn’t bother him, but we also know who he is and what he’s done.”

The First Lady has been around politics long enough to know when to stop talking, and when I try to push her, she greets my prodding with a polite smile: “I should probably leave it at that.”

• • •

“HAVE YA TALKED TO THE FORMER PRESIDENT YET?” McAuliffe asks me by way of saying hello. It’s late June, and we’re back in his office. The furor surrounding the federal investigation of McAuliffe has died down for the moment, and he’s back to his exuberant self. “I just gave him my blessing to talk to you. He’ll call you soon.”

I ask the governor what his relationship is like with Bill Clinton now that their roles have reversed—does he ever ask Clinton for advice? McAuliffe says they talk several times a week about “everything.” They still play golf. (“He keeps score. It’s just uncanny how every time I happen to lose by one stroke.”) But there’s no protégé/master dynamic. McAuliffe calls Clinton to share updates on what he’s done and what’s happening in the Commonwealth. “Pure friendship at this point,” he tells me. “I mean, he is SO jacked up.”

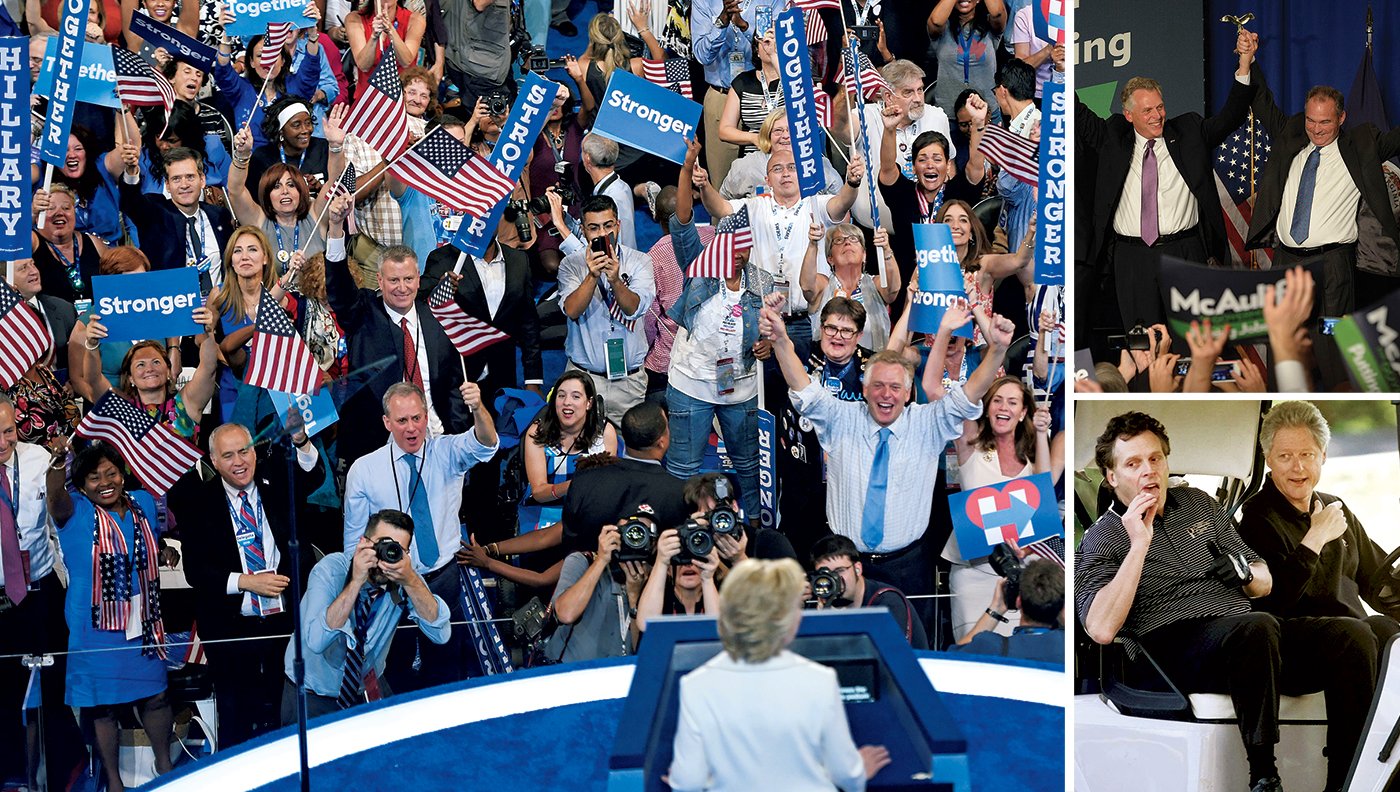

Talk of the former President leads to talk of the next possible President Clinton. This was more than a month before Hillary would pick her running mate, and McAuliffe waved off some of the contenders (HUD Secretary Julián Castro and Senator Cory Booker of New Jersey). He described to me how he’d been prodding her to tap Tim Kaine—and that’s just what she did.

McAuliffe later said he was “thrilled” with the pick, even as Kaine’s selection puts the governor in the tricky spot of filling the junior senator’s seat if the Clinton/Kaine ticket wins in November.

I had heard rumors McAuliffe was pushing Kaine so he could appoint himself to fill Kaine’s Senate seat, but when I asked McAuliffe about it, he flatly denied it: “There is no chance I would do it.” Under state law, whoever replaces Kaine in this hypothetical scenario will have to run in a special election in 2017 and again in 2018 for a new six-year term, and McAuliffe looks askance at the prospect of back-to-back statewide races. Besides, he can’t see himself trading the power of an executive office for the gridlock in Congress. “I like to make a decision and implement it immediately,” he says.

What is certain is that come 2018, McAuliffe will no longer occupy the most historic state mansion in the nation. Virginia is the only state with a single-term governor, and to hear McAuliffe reflect these days, that suits him just fine. “I couldn’t do this for eight years—I get antsy,” he says.

It’s also hard work. For another year in a row, McAuliffe wasn’t able to convince state lawmakers to expand Medicaid—his biggest legislative goal and a campaign promise. That budget surplus he bragged about to me has turned into a $266-million deficit for 2017. He’s left to wait for the conclusion of the federal probe into his personal finances and ties to foreign governments. And oh, by the way, Stone Brewing is actually calling his personalized beer Stone Give Me Stout or Give Me Death. (A spokeswoman for the brewery says it does plan to reference “Your Excellency” on the back of the label.)

So what will McAuliffe do next? If Hillary Clinton wins the White House, it’s no stretch to picture the First Friend running the Commerce Department, say, or serving as US trade representative. He seems open to these prospects, but also kind of indifferent. He did himself no favors at the Democratic convention in late July, stepping all over the party’s “Unity” message when he told a reporter that Clinton, if elected, would sign a version of the controversial Trans-Pacific Partnership trade deal. (Clinton had already flip-flopped on her previous support for the TPP in an effort to placate Bernie-loving liberals.) McAuliffe quickly backtracked, senior Clinton aides rebuked him, and Donald Trump seized on the gaffe to deflect attention from his comments urging Russian hackers to target Clinton. “Just like I have warned from the beginning,” Trump tweeted, “Crooked Hillary Clinton will betray you on the TPP.”

I suspect that in his heart McAuliffe hoped a successful term as Virginia governor would put him in contention to be Hillary’s running mate. Instead, he’ll probably settle for a cushy diplomatic post.

And what’s a four-year stint to London’s Court of St. James’s if not one long party? Mister Ambassador: The words ring almost as sweetly as His Excellency.

This article appears in our September 2016 issue of Washingtonian.