Of all the momentous visits made to the nation’s capital, one of the most momentous was in the summer of 1941, when Irene Kerchek, a 17-year-old from St. Louis, came east for the first time to visit her Aunt Fanny. Irene met Abe Pollin, and the two went on to be one of the founding couples of modern Washington.

After breaking away from the Pollin family’s construction business, the two built a real-estate empire of their own, then brought Washington its first professional basketball and hockey teams—and its only NBA championship, in 1978. They also gave us our first true arenas, the now-demolished Capital Centre in Prince George’s County and the one currently known as the Verizon Center. The latter, which rose in downtown DC as the city’s darkest days were ending, jump-started the ongoing boom.

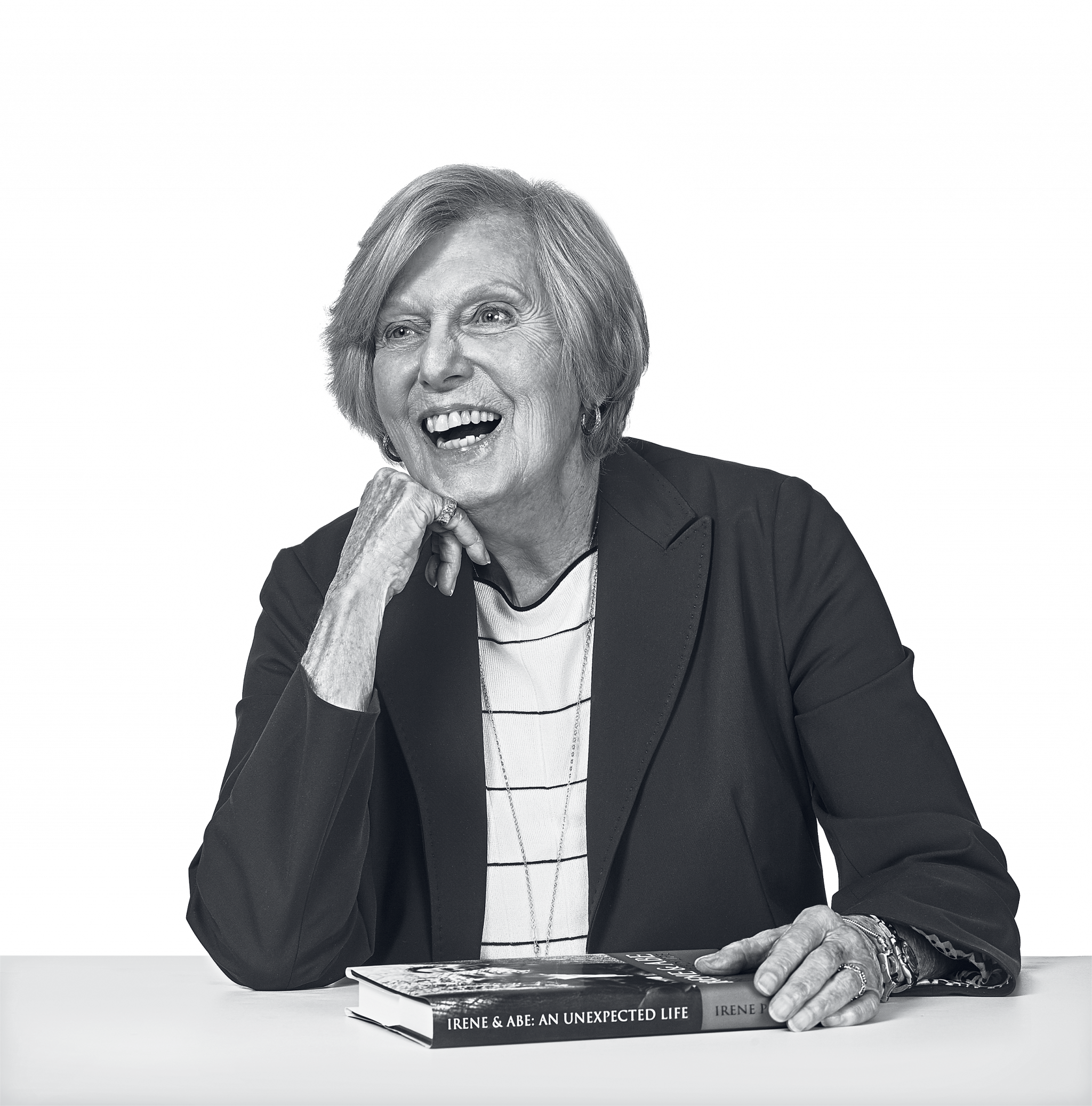

Now 92, and a widow since 2009, Irene Pollin has published a memoir, Irene & Abe: An Unexpected Life, about the way in which many of the couple’s triumphs were motivated by the deaths of their son Kenneth at 15 months and their 16-year-old daughter, Linda, both of a congenital heart condition. She talked about her life at her home in Bethesda.

In the book, you recall your first impression of Washington, just before the Second World War. You say it was sort of a Podunk town.

It really was. I was shocked. In St. Louis, we had wonderful art museums, we had Washington University, we had a fantastic park and very established communities. I just took that for granted. When I came to Washington, I remember going to the National Gallery for the first time, with my husband. I said, “Where are all the paintings?” You could drive up to the Washington Monument, park in the front. F Street, downtown, had shops, mostly on one side, from 7th Street to 14th. As girlfriends on a Saturday, we’d start at 7th, where the Hecht Company was, and walk up to 14th, where Garfinckel’s was. Woodward & Lothrop was in the middle. That’s it.

Do you remember where you’d eat?

I think Garfinckel’s had a little tearoom.

As small as the city was, you point out that it was divided into discreet worlds of business and politics and media.

It’s still very separate. It really hasn’t changed much. To this day in my book club, I’m the only one from the business community. And I became a part of that group only after Abe and I went into professional sports. We were in an unusual position because we owned the Cap Centre—we became interesting to the media people and the politicians.

Whom did you socialize with?

My father-in-law belonged to a small group of Jewish businessmen who were in construction or something related—plumbing and heating. There was a cluster of seven or eight guys who met regularly and were very close—Morris Cafritz, Charlie Smith—that was my father-in-law’s cohort. They would buy Israel bonds, and my father-in-law bought tickets to every Jewish fundraiser. We didn’t have to go out to see each other, because we’d see each other anyway. We were like family.

Yet later you became close to Yitzhak Rabin, who later was prime minister of Israel, and his wife. How did that happen?

After our daughter died, we decided to start a scholarship for an Israeli female student to come to the US and study. We just walked into the Israeli Embassy and were introduced to a guy there, Ephraim Levy, who started inviting us to dinners at his house off of New Mexico Avenue. There would be us and one or two other couples. It was fun and always interesting, but it was odd: All these men would come and go—single men. They would go into the kitchen and talk a while and then leave. Only later did we realize that these little dinner parties were a perfect cover for Ephraim [to meet with American officials]. We met Jim Angleton there, the CIA man.

One night at about 11, the doorbell rang and it was the Rabins. They’d just arrived in Washington, right off the plane. Leah [Rabin] was still wearing her fur coat. She loved tennis, and we had a neighbor who had a tennis court. We became close friends.

This was the ’60s, when the suburbs were exploding. Were you part of the boom?

Our first house after we were married, in Silver Spring, was one of a group of houses that my husband built. Outside of that, no, because after that we went into apartment buildings. Even when we built in Virginia or in Chevy Chase, it was apartments.

Why not? Suburban Washington was exploding at that point.

Well, first of all, we separated from the family business at that point. My father-in-law had this fantasy of Morris Pollin and Sons, with the three sons working together. But that didn’t work out.

As the ’60s progressed, DC began to hollow out. Did it change how you did business?

My brother-in-law built a building on Massachusetts Avenue, around 12th Street, and it really struggled. It was dead. Nobody wanted to go down there. We had built the James, which initially struggled, but it went all right. It had the first pool on the roof.

Wait—you started the rooftop-pool trend?

At the time, it was the first new building in that part of town. We were asking ourselves: How are we going to draw people to the building? We decided to give them a reason to move downtown.

Were you worried for Washington?

Well, it depends on which part of the ’60s you’re talking about. My daughter died in ’63, and we bought the Bullets in 1964. Once we were in sports, it took us into a whole new world.

You describe the aftermath of your daughter’s death as a lost time, not only in your grief but because you were put on tranquilizers. Do you regret dealing with your grief in that way?

I didn’t have a choice.

You felt the drugs were necessary?

It wasn’t that I felt—there was nothing else. I went from therapist to therapist, psychologists, psychiatrists. Not one knew how to deal with the grief. I just wanted to function. That first year, my husband and I just sat here, and I really struggled. Eventually, I went to school and got a degree in anthropology at AU, and I went to work for the Peace Corps. But I was swallowing Valium in the elevator to get to work. It wasn’t until I started at Catholic University and got my master’s in social work that I saw how to use those 16 years I spent raising my daughter, put them to some use.

That eventually became the basis of your work as a therapist.

If you are a normal, functioning person who has a severe trauma, as I did, it’s not that you are struggling with your neuroses. It has little to do with your mom or your dad, but the fact that you were dealing with grief. So I created medical crisis counseling focused on chronic illness and the family dealing with it.

Many years later, your husband left you, not once but twice. You attribute that in part to the way he buried his feelings about the loss of your children.

He always did, from the time he was 17. People see him as very calm, and he was. I would say, “He looks calm.” When our son died at 15 months, he didn’t say his name for a year.

It was buying the basketball team that got him past the grief. Was that intentional?

It was a fluke. After we’d been sitting around here for a year—Abe didn’t really even go to the office—he got a phone call from this friend he knew through the Jewish Community Center, who said there’s this opportunity to buy the Baltimore Bullets. Abe came to me and reminded me that I had been a big sports fan in my youth. I said maybe later. He kept after me, saying it could be a distraction. Looking back, I see that it was.

Owning a sports team seemed simpler then.

Not too many sports owners spend the time that we did with the players. We had dinner with them, we took the bus with them. We went to China with them, to Israel with them. It was a rare opportunity.

You built the Capital Centre in Landover in 1973 and the Verizon Center 25 years later. In both cases, you got tax breaks from the local governments, but nothing like what owners extract from cities today.

Even then, when we built the Cap Centre, I think we were one of the few teams to do that. We had to sell some of our properties, the James and the Apolline. If it hadn’t worked out, we’d have been in trouble. There were offers from Northern Virginia and Baltimore and near Columbia, and for some we wouldn’t have had to put up a penny. It was more gratifying, though, to get this built.

Was it part of the plan with the Verizon Center to revive downtown?

Some things were already happening on the fringes. We were hoping it would do something for the neighborhood. What really did it was the subway. Suburban parents thought it sensible to send their kids down on the subway and pick them up after the game. That had never happened in Washington before.

Did you think it would change DC as it has?

We were quite aware of what was coming. At the time, we could have purchased a lot more property around the Verizon Center. We could have bought it for a song. But my husband said no, because we would be seen as greedy. The town would have said, “Oh, you took advantage.” Other people—other owners I can think of—would have.

You moved the Bullets here from Baltimore in 1973 for financial reasons—Baltimore really couldn’t support a team. But there was no guarantee Washington would, either.

It’s really an ongoing problem in Washington. It’s not like any normal city.

Because people root for their home teams?

Yes, but Washington also has other things that are more important—fundraising, fundraising, fundraising. To make a team work, you have to get TV coverage. I don’t know about now, but when we started the Capitals, TV revenues would support us to a point—to here but no further. We could fill every seat and still not make money. My husband didn’t like having other investors, the way [current Capitals owner] Ted Leonsis does.

Your son Robert, an economics professor at the University of Massachusetts, wrote an op-ed calling on Dan Snyder to change the Redskins’ name. Do you agree with him?

No. I’m a team owner. Only the fans can tell him to change the name, by not appearing at games. Dan Snyder is a businessman. As long as people buy tickets, why would he change?

Yet in 1995 you changed the name of the Bullets to the Wizards, partly on principle.

My husband felt very strongly after Rabin’s assassination. We’d had lunch with him just the month before. The events kind of pulled it all together. But we had a different reason. We wanted to have a distinctive Washington name. Dan Snyder doesn’t have that problem.

How important is winning?

There’s only one reason an owner wants to be an owner, and that’s to win. It’s not about money. Very few teams actually make money. The question is: What does it take to win? How much control do you have over that? We were in it for 46 years, and this time of year for 46 years, Abe and I would be talking about new players, new coaches—we’d be talking about it up in our bedroom. We had hundreds of people working on it. We were lucky enough to have a championship, which is rare. But then you ask: What was the combination that year that we didn’t have other years? A lot of things have to come together.

The reality is you lose more than you win.

Exactly, and what does losing year after year do to your psyche? Reporters called us cheap, said we didn’t want to win. Abe got spit on by fans. The fans are so invested. In what other business do you sell something to someone and they feel like they have ownership? But of course that’s what makes it so special.

This article appears in the November 2016 issue of Washingtonian.