Alex Wirth and Jonathan Marks went viral for the first time in February 2015. It had started with a hunch, after Wirth read a New York Times story about women on Capitol Hill. The 114th Congress has more female members than any before, but by and large they aren’t in control of committees or other power centers. Wirth asked Marks to use their analytics platform to run some numbers.

What came back was visceral evidence that the women in Congress actually have a hidden power: They consistently introduce more bills than their male counterparts and are more successful at getting them out of committee and into law. The data also showed that women senators are more bipartisan in their cosponsorships, crossing the aisle for an average of 171 bills, compared with 130 for the men.

Wirth and Marks sent their data to a Times reporter, Sheryl Gay Stolberg, whom Wirth knew through a Harvard project. Stolberg then published a new story about the revelations, beginning with the words “A couple of enterprising Harvard University students have uncovered proof of what women in the United States Senate have long suspected and claimed. . . .”

Yep, Wirth and Marks were still in college at the time. Their company, Quorum, was only a month old, launched over their winter break. And now anyone who read the Times—or Bloomberg, Jezebel, the Huffington Post, or Mashable—or who watched cable news suddenly knew about the two Harvard seniors scheming to spark a big-data revolution on the Hill.

“We want to be the equivalent of the Bloomberg Terminal,” says Wirth. “What that is to New York, Quorum is to Washington. If you show up to work, you’re logging in to check your Quorum dashboard—to talk to your team, to do your outreach, to do whatever your job is.”

Since its buzzy debut, the company has continued cranking out the sticky charts and graphics that all the explainery websites and blogs crowding the internet today feast on. At the same time, Wirth and Marks have signed up a passel of heavy-hitter clients who pay into the six figures per year: Arnold & Porter, Covington & Burling, the Glover Park Group, the United Nations Foundation, General Motors, Toyota, the Podesta Group, the Club for Growth, and House majority leader Kevin McCarthy among them.

“A bunch of Ivy League kids have come into an old-boys’ town and made everybody take a second look at doing business,” says Andrew Mills, federal-affairs director at the Niskanen Center, a libertarian think tank and a Quorum client.

That someone would come along and quantify what was once only intuition isn’t all that surprising. Everybody wants to be the Moneyball of something these days. What’s surprising is how readily a town that makes deals over handshakes and stuffed mushrooms has embraced these pups.

Oh, yeah, and did we mention they all live together?

***

Stepping into Quorum’s cable-strewn group house turned company headquarters is pretty much like turning on HBO’s Silicon Valley, if there were a DC Wonk edition. Computer monitors—at least two to a person—loom over the coders’ hunched frames. There’s a Donald Trump piñata on the mantle and a drone on the water cooler. One coder’s MacBook rests, inexplicably, on two copies of former Maine senator Olympia Snowe’s memoir.

Office culture is pretty much what you’d expect of overeducated, politics-obsessed programming nerds who want to change the world. One afternoon earlier this year, Marks and an employee named Larry Moore mulled over a coding problem. “Fedora, give me insight,” Moore said, reaching for a hideously powder-blue hat. “Programming skills upgraded,” he deadpanned to a chorus of groans.

“Social skills downgraded,” jeered a colleague.

The house—a seven-bedroom Craftsman—sits on a quiet block in Friendship Heights. Marks and Wirth went for it because it’s nothing like the narrow, sunlight-starved rowhouses they could have rented in a trendier neighborhood like H Street or Shaw. Also, unlike the skeptical landlords they met who didn’t want their house turned into a computer lab, this one’s was enthralled. “We might’ve pushed the Harvard angle a little far,” Wirth says.

So Quorum is a lot different from its competitors headquartered closer to K Street and Capitol Hill, and not just in appearance. Yes, like CQ Roll Call, National Journal, Bloomberg Government, and Politico Pro, it pushes out high-priced political intel for lobbyists and companies that monitor minute changes in policy. As with the incumbents, Quorum’s platform features bill tracking, social-media alerts, a searchable Congressional Record, and tools to connect and set up meetings with staffers.

“I remember when we were approached about Quorum, I said, ‘I really don’t need any more information,’ ” says Chris Cushing, managing director at Nelson Mullins who’s been a lobbyist for three decades. “There was enough information coming in from these multiple subscription sources that we already had. But no one was doing what Quorum did.”

What it does is essentially vacuum up every possibly telling piece of publicly available data about every member of Congress: voting decisions (373,000 a year), cosponsorships (77,000), press releases (70,000), floor statements (24,000), Facebook posts (185,000), tweets (414,000)—some 14.6 billion data points in all annually. Then it uses a proprietary variation of Google’s PageRank algorithm to crunch the data and spit out analyses of which members are the best influencers and who their strongest allies are.

What you end up with, if you’re a lobbyist, activist, or lawmaker, is a blueprint for turning an idea into a law. Which member of Congress is most effective in your issue? Quorum will tell you. Whom does that member work with most frequently, in case you need somewhere else to turn? Quorum will tell you. The platform offers more than 100 statistics per legislator across 1,000 issue areas since the 101st Congress, including how many bills he or she gets out of committee and how often that bill is signed into law.

We want to be the equivalent of the Bloomberg Terminal…What that is to New York, Quorum is to Washington.

When a railroad client asked the law firm Holland & Knight which Congress members it could get to champion projects that would be most likely to qualify for federal transportation grants, the platform slashed the effort involved. “We used Quorum to help us create this list of legislators that had high influence scores and high bipartisanship scores in these particular issues,” says Paolo Mastrangelo, senior public-affairs adviser at the firm. “We literally picked them out by state. . . . Of course, we gut-check them with what we know about the members and what we know about the state and all that, but it was another layer of data and information that otherwise would’ve taken me like two years to do.”

You can see how that would make Quorum’s software applicable and valuable in any era, but clients say it has value added in this era of extended gridlock.

“Once upon a time, a tax lobbyist in this town could have dinner and drinks with a powerful committee chair at Morton’s in Georgetown and get a lot of work done for his clients,” says Jack Quinn, former White House counsel to President Clinton and chairman of QGA Public Affairs, another Quorum client. “It doesn’t work that way anymore.”

Term limits on committee chairs and the end of earmarks—which party leaders doled out to keep their members in line—have dissipated power toward less established lawmakers, so turning its levers is more work. In cases where bipartisanship is a necessity—say, getting the 60 votes to overcome a filibuster—it’s a lot easier if you have a quick way to ferret out the quiet bipartisan relationships that do exist.

Quorum, says Cushing, “can demonstrate connections that you may not have thought about. One or two or three additional lawmakers working on an issue can make all the difference for your client’s success.”

***

Wirth and Marks met on a Harvard backpacking trip through the Appalachian Trail the summer before freshman year.

Marks, 24, who hails from Wisconsin and comes from a long line of cardiologists, talks with the clinical straightforwardness of the family trade. At a Quorum bowling outing last spring, one of his employees told the biology/computer-science graduate that he should become the company’s in-house MD. “That wouldn’t be that hard for you, would it?” she asked, remarking on his aptitude in most endeavors. Most endeavors—at said outing, he asked the group if they could get gutter bumpers.

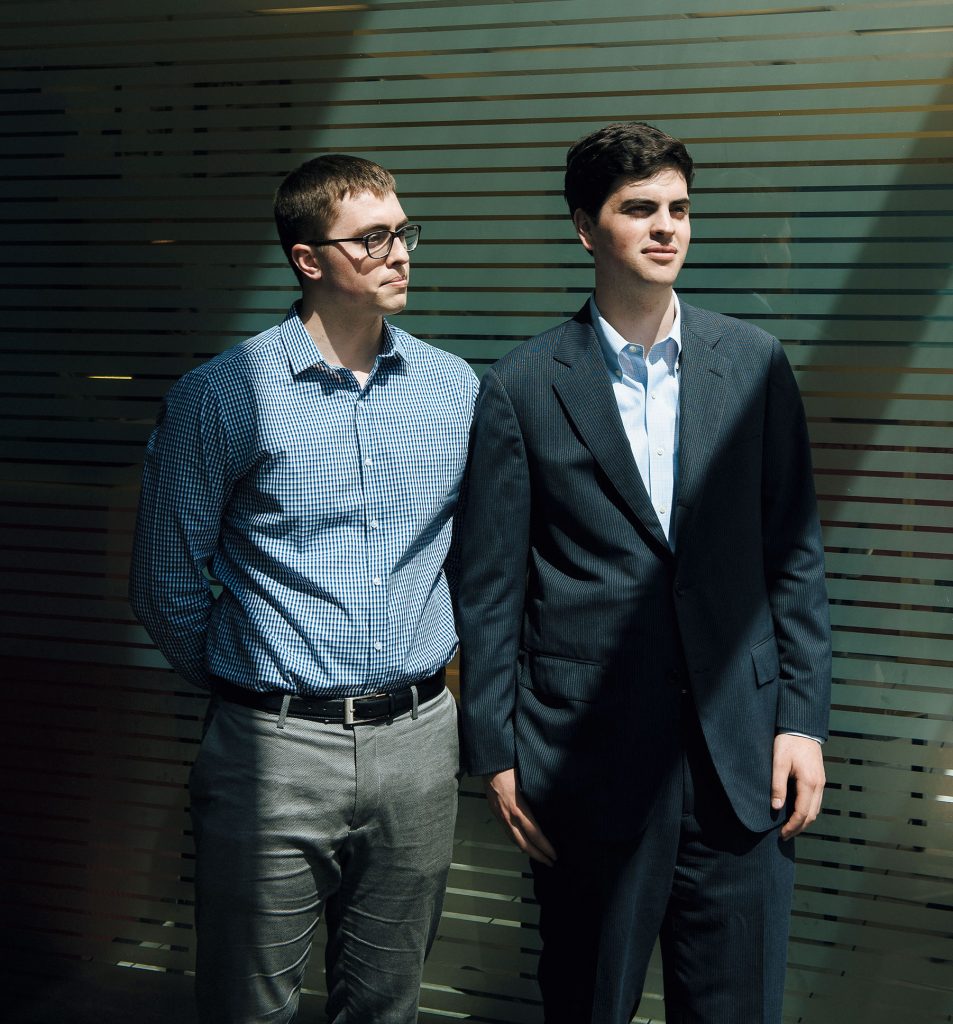

Marks is the mind behind the machine, the Quorum quant who manages programmers at the Friendship Heights house in socks and sweatshirts. “Alex is the face of Quorum,” as he puts it. “I am the brains. And the brawn.”

That makes Wirth, 23, the one onstage giving TEDx talks and meeting clients on Capitol Hill. He’s from New Mexico, a grand-nephew of former Colorado senator Tim Wirth and a former Senate page. As you might expect of a guy who has spoken to the United Nations and the Clinton Global Initiative before his mid-twenties, he’s also the half of the company who pimps any mention it gets in Politico’s Playbook.

The genesis of Quorum dates to the summer after their freshman year, which Wirth spent in Washington pursuing an endearing student-council-like idea. He thought the White House should have a youth advisory council. He wanted an executive action from President Obama to make it happen. He was only 19.

Wirth trapezed around Capitol Hill trying to build support. “I was keeping track of it in a long Word document,” he says. “I ran head-on into the challenge that many folks face on a daily basis in DC, which is that the information is so scattered that it’s hard to keep track of. It’s really difficult to figure out who are the key players on a given issue.”

Marks had spent the summer working at a computational-biochemistry lab—also studying relationships, just ones between proteins and metabolites and other biological arcana. “It turns out that the math that you use to understand the most important proteins in a network,” says Marks, “is really not that different than the math you use to understand which members of Congress are most important in a network.”

The roommates sketched out a few concepts, built prototypes, applied for an entrepreneurship class. The collection of code that would become Quorum got its first test in 2014 when they demonstrated the platform for former US senator Jeff Bingaman. Before the meeting, Wirth and Marks gave it a test run. The data that came back astounded them, and not in a good way. “[It said] his most effective issue area was the Marshall Islands,” says Wirth. “And I’m like, ‘There’s not a chance.’ ” Bingaman represented the landlocked state of New Mexico, thousands of miles from the mid–Pacific Ocean territory.

But there wasn’t any obvious error. So they went with it. During the meeting, they took their time to get to the takeaway about the Marshall Islands. “And he looks at it, and his face suddenly lights up and goes, ‘Oh, yeah, that does make sense!’ ” Wirth says.

Turns out Bingaman’s chairmanship of the Energy Committee gave him jurisdiction over US territories and islands. “They always used to come to me and ask me to be the sponsor or green-light [bills],” Wirth recalls the senator saying.

The conceit for Quorum was validated. Its data was good, and it revealed an insight that even the senator didn’t know about.

A little grant and prize money rolled in—about $80,000—which gave Wirth and Marks the ability to pay their first student employees. (The founders initially went without a paycheck.) In May 2015, Wirth and Marks graduated on a Thursday. By Monday, they had their first computer lab/house set up in DC.

Today, Wirth loves to tout the company’s ability to survive only off its subscriptions, paid for by more than 100 clients. The fees range from $3,600 for data on a single state legislature to hundreds of thousands of dollars for a large team accessing federal, state, and other data. “We’ve been cash-flow-positive from day one,” he says. There’s no big-shot VC with a majority stake, no faraway investors calling the shots—just he and Marks and their high-minded devotion to the cause.

“I want to spend my life building things,” says Marks. “And I want to spend my life working on companies that make a difference.”

“We’re not gonna go try and start a dating app,” says Wirth.

“We did do that once at one point,” Marks interjects.

“We talked about it—we didn’t do it,” insists Wirth. “These are the types of ideas you come up with when you’re in college. And why many college start-ups fail.”

***

The funny thing is that Wirth and Marks have gone to some pretty drastic lengths to recreate the best parts of college for their newly graduated employees. They’re usually hosting a pet from DogVacay.com, an Airbnb for animals. (“[We] thought of it as an internship for our furry children,” wrote one five-star reviewer. “They came home happy!”) The house/office has an eight-seat movie theater in the basement for Super Bowl parties, movie nights, and group binge-watching of—what else?—The West Wing. Down the hall is a steam room plus a laundry room where the washer/dryer is going “pretty much constantly,” according to Wirth.

“When you come out of school, it is frightening, this whole real world,” he says. “Shit, I gotta find a place and pay rent every month. Well, now I’ve gotta pay utilities. Now I gotta get on the phone with Comcast, Pepco, and Washington Gas. Oh, by the way, I need to go shopping, I need to make a meal for myself every evening. Now I gotta do the dishes.”

So the company mitigates the scary world of #adulting by paying the rent, utilities, and grocery bill for their live-in employees. Just about every night, Marks or another employee cooks dinner with Costco-size ingredients and steam trays. It’s basically like the crazy perks—a shuttle to work, free food all day—that you get working for Apple or Google out in Silicon Valley, but adapted for a DC millennial and factored into a DC-size paycheck. (Wirth describes that as “market rate.”)

“Something that really strikes me is their discipline,” says Susanna Quinn, founder of the fitness-and-beauty app Veluxe. “I mean, you take a bunch of young guys and you move them into a house together and you’d expect they’d just go down to Adams Morgan and go drinking.

“Can you imagine if all 22-year-olds were like this? China wouldn’t be a threat to us.”

Quinn knows the Quorumers through the tech scene as well as through her husband, Jack, their client. The two are among the many grown-ups—clients, VIPs—whom Wirth and Marks have invited over to eat and network with the gang. You can picture the scene: a Washington dinner party, except that the guests always want a tour of the dorm. The effect, inevitably, is to make the would-be clients feel a sense of attachment to those nice, nice young men. It gives the big shots something to talk about next time they’re at a more typical Beltway dinner: just like that, more buzz for Quorum.

“Of course I’m thinking, ‘Oh, my God, I so want to bring in some rugs,’ ” says Quinn. “And I want them all to have bed skirts. I keep meaning to send bed skirts.”

***

On the night of the Congressional Baseball Game this past summer, Quorum’s team is massing outside Nationals Park. They’re carrying some 20,000 Quorum-branded baseball cards with legislative stats for all the members playing in the game. You can probably imagine what the bottom of each card says: “Come and see why the Washington Post called us Moneyball for Congress.”

It’s perfectly on-point marketing material. If you’re the kind of person who spectates at the Congressional Baseball Game. Sure enough, once the handout begins, the fans go wild—they’re asking for their home-state senator’s cards, their boss’s. After taking a handful, two bro-ish guys check out each other’s haul. “You got two Republicans? I got a f—ing Democrat,” one says.

Of course I’m thinking, ‘Oh, my God, I so want to bring in some rugs.’

You can practically see Wirth licking his lips. “What’s fun about this is that this is the CQ Roll Call game,” he says. “That’s the sponsor. They’re our competitor. And we’re about to steal the whole show with a couple thousand baseball cards.”

In a way, the scene is a reminder of how far Quorum has come in the barely two years it’s been a thing. From here, though, the path may be tougher. Rivals are trying to steal some turf, and Capitol Hill itself is a potential obstacle to the company’s growth. Congress is still strikingly untransparent—it wasn’t until this past February that it began publishing portions of its data in a machine-readable format. Plenty of important information such as committee votes is still hidden inside formats that aren’t easily combed by automation.

“The tough part for us is pushing Congress to start making more information available to the public,” says Wirth. “We’re able to access significant amounts of information now, but the more information we’re able to access, the more interesting things we can do with it.” The company has partnered with a group of think tanks and open-government organizations to lobby for better access.

That could be the difference between Quorum present and the Bloomberg Terminal–style Quorum of the future that the cofounders envision. The company’s clients today see the platform as a vital tool in the toolbox, but not all-consuming yet.

“They do have a secret sauce,” says Cushing. “But I don’t think anybody is going to give up Politico or give up Bloomberg. When you’re representing clients, you need all these different sources of information.”

As for the house in Friendship Heights, the group dinners, the trips to the bowling alley: “We’ll see how long it lasts,” says Marks. “This idea does not scale indefinitely.” People getting older, he says—maturing, moving in with significant others.

Quorum is up to 25 employees and recently rented two more homes to hold them all. Meals have gotten so large that the company now gets bulk truck deliveries from Sysco. A summer hire, Michael Gasparovic, is the new cook. He’s a coder who once worked at a two-Michelin-star restaurant. Spreadsheets and ingredient tracking are employed. Naturally, dinner prep now involves data mining.

Staff writer Michael J. Gaynor (@michael_gaynor on Twitter) can be reached at mgaynor@washingtonian.com.

This article appears in the November 2016 issue of Washingtonian.