It’s a Tuesday night in November, and 700 people have bought tickets to a sold-out party hosted in part by the craft brewery Flying Dog. It’s not the kind of party where beer geeks nerd out over warrior hops and mouthfeel; there’s a low ratio of beards to business casual here.

Nor is the setting one you’d probably expect. This party is in the Newseum, under the cosponsorship of something called the 1st Amendment Society, a pet project of brewery CEO Jim Caruso. He’s also the evening’s headliner. And he’s not here to talk about beer.

As bartenders serve bottles of Flying Dog in five bars across seven floors, Caruso takes the dais. To his left sits Alan Gura, the lawyer best known around Washington for arguing District of Columbia v. Heller, the Supreme Court case that struck down DC’s handgun ban. A legal celebrity in libertarian circles, Gura has represented Flying Dog, too.

The case that brought Gura and Caruso together—and turned Maryland’s largest craft brewer into a political activist of sorts—isn’t that familiar to the 55,000 fans who make pilgrimages to Flying Dog’s Frederick brewery each year. And it has nothing to do with a high-profile subject like guns in the nation’s capital. The case involved whether Michigan’s alcohol-control bureaucracy could forbid the company to market a beer with an off-color name.

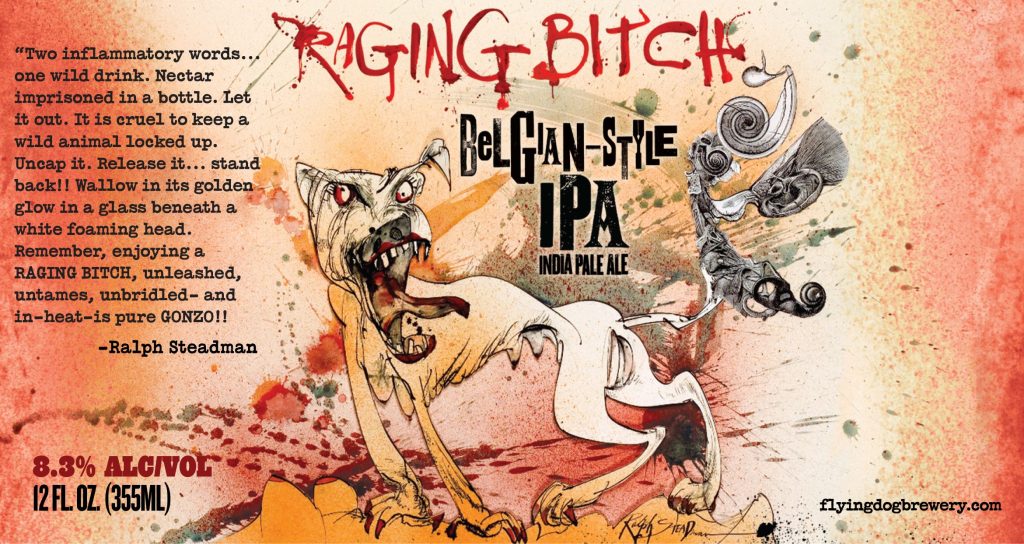

But within the company, the legal war over Raging Bitch Belgian-Style India Pale Ale is practically scripture—a foundational text. His bottle of Raging Bitch at the ready, Caruso launches in.

“The name comes from—pretty simply, we use El Diablo yeast,” Caruso explains, emphatically drawing out the name. “It’s a raging yeast. It ferments very aggressively. Bitch is a dog. Raging Bitch. Yes, we know there’s other connotations, but we chose that name and all of the ladies at Flying Dog voted unanimously to do this beer with that name. We asked our artist, Ralph Steadman, to do some art for it. ‘Ralph it up a little bit,’ we said. ‘It’s our 20th anniversary. We don’t want to look like we’re getting boring.’ ”

Steadman—the gonzo artist who illustrated Hunter S. Thompson’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas—does not do boring. For the label, he drew a mangy red-eyed dog with drooping breasts and grossly accentuated female genitalia. The Bitch’s mouth is wide open, its sharp teeth bared and its advancing tongue covered in blood. It looks menacing and deranged.

The IPA was an instant hit—named one of the top ten new beers in the US by Modern Brewery Age in 2010. But Michigan regulators had an entirely different issue: the name. They banned the beer from stores, calling it “detrimental to the health, safety or welfare of the general public.”

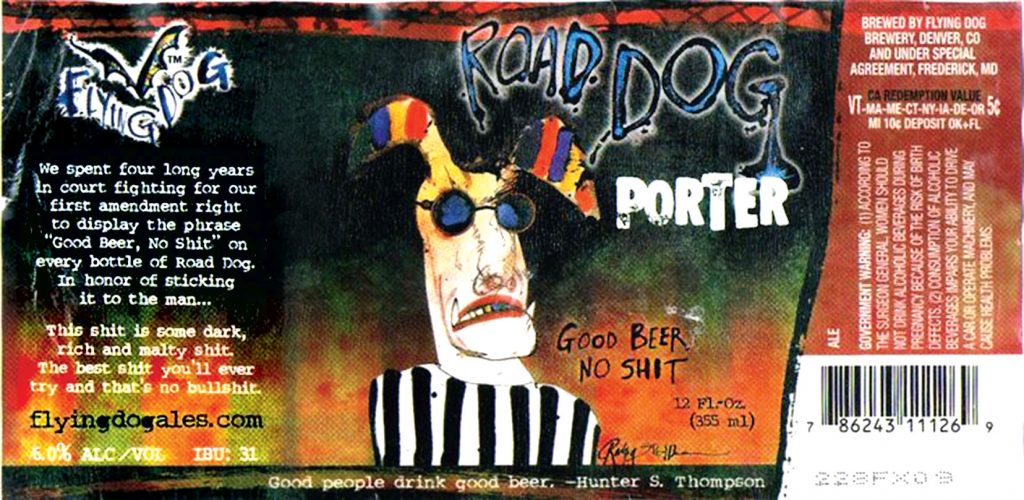

At 62, Caruso is easy to like—just a regular guy in jeans and a black work shirt embroidered with the Flying Dog bat wings, taking big swigs of Raging Bitch between mike handoffs. Tonight the standing-room-only crowd is all his. Young, old, but mostly young, they laugh every time his uptalk implies they should, which is often. They laugh as Caruso recounts a long history of battles against political correctness, dating back more than 20 years, when the brewery wanted its first Steadman-designed bottle to proclaim, “Good Beer, No Shit.”

After he’s done, fans hang around for photos, lining up like true believers waiting for a grip-and-grin with their favorite Washington pol. Instead of “Cheese!,” Caruso looks into the camera each time and issues the Flying Dog battle cry: “Good beer, no shit!”

***

This story is worth telling not just because Caruso defies the heavily bearded, heavily tattooed stereotype of the craft-beer guy—he’s a muscular black belt in karate who wears his receding dark hair neatly combed back—but because unlike most CEOs in a mostly apolitical business, he says he runs a “libertarian brewery,” blogs about his politics on the company website, and likes to hat-tip Reason.

It’s worth telling because Flying Dog is the biggest craft brewery greater Washington has. It ships 125,000 barrels of beer a year to 27 states and 22 countries, more than Devils Backbone before AB InBev took it over (67,000 barrels), Baltimore’s Heavy Seas (roughly 50,000), and DC Brau (15,000).

It’s worth telling because Flying Dog is distinctly, even stubbornly Maryland. It brews beers with Old Bay and Rappahannock River oysters and donates proceeds to the Oyster Recovery Partnership, which works to bring back the Chesapeake oyster population. It sells Flying Dog bumper stickers that bear the heraldic colors of the state flag.

It’s worth telling because Raging Bitch—which Caruso tells me is sometimes ordered simply as “an ex-wife”—is the company’s most popular beer. Believe it because it’s true: The beer whose label says “Remember, enjoying a RAGING BITCH, unleashed, untamed, unbridled—and in heat—is pure GONZO!!” has been the brewery’s number-one seller ever since it was introduced seven years ago.

And that’s hardly the most audaciously named brew in Flying Dog’s at-worst-misogynistic and at-best-sophomoric catalog. Consider: Doggie Style Pale Ale (“The moment you lay claim to having it, it’s gone”), In-Heat Wheat (“A sword swallower taunts the crowd as they chant deeper, DEEPER!”), and a charming brew called Pearl Necklace Chesapeake Stout (the NSFW version of which is not a piece of jewelry).

“The double meaning to me personally is just hilarious,” says senior communications director Erin Weston. “When people talk to me about it and they’re like, ‘How could you support a beer like that?’ And I’m like, ‘What? I own my grandmother’s pearls—what are you talking about?’ You know, to just be purposely ignorant about it.”

The brewery that put Maryland on America’s craft-beer map is the same one that markets the world’s oldest, most obvious female slur. More than that, the mutts have made a cause of defending their Bitch. Isn’t there something kind of messed up about that?

***

When Caruso told me he ran a libertarian brewery, I thought he was joking. This was before I’d spent much time in the Frederick taproom, back when I thought all breweries were near myopic about what’s in the glass.

Flying Dog is somehow about both. In the back, there are the engineers in T-shirts and Carhartts who make the beer, the sticklers for quality control who hide six-packs under space heaters to test the brew’s resilience.

Then there are the beer stewards and tour guides up front who hawk the Flying Dog “story.” It’s a tale of underdogs and independence and counterculture, and it begins with a Colorado physicist who is also heir to the Champion Spark Plug fortune.

“Nobody had ever connected the words ‘flying’ and ‘dog’ together . . . until 1983, when George Stranahan was itching for an adventure,” the brewery’s website reads. Stranahan was in the Himalayas climbing K2 with a band of buddies he called the Innocents when disaster hit: “[O]n day 17 of a 35-day trip, we totally ran out of booze.” From there the story skips ahead, to a hotel bar in Pakistan where the Innocents settled in to make up for lost buzz. That’s when they saw it.

“It was a full-on oil painting of a dog, a beautiful oil painting, big, nice. And the dog was like . . . well, he had left the ground. Here we were, the March of the Innocents and this ‘Flying Dog,’ and the weirdness of it all. . . . They fit together in some way.”

Seven years later, in the early first wave of the craft-beer boom, Stranahan established an Aspen brewpub called Flying Dog. Within a few years, it was brewing beer on a ranch in Carbondale, Colorado. But when fuel prices spiked in the early 2000s, the company looked east to offset shipping costs. Flying Dog brewed its first beer in Maryland in 2006, taking advantage of the warm slipper left behind by the bankrupt Frederick Brewing Company. A year later, it consolidated all its operations in Frederick, just south of the Catoctin Mountains. (Or as Coloradans call them, hills.)

Caruso has been at the helm much of this time. “In life, you can stand for something or stand for shit,” he says. It’s his own philosophy, but the company’s, too, all the way back to its roots.

In the “Good Beer, No Shit” fight of the early ’90s, Stranahan spent five years standing up for Flying Dog’s right to curse on the label of its Road Dog Scottish Porter. Regulators thought the slogan was offensive. While they hashed it out, Flying Dog replaced the phrase with “Good Beer, No Censorship.” When the brewery eventually prevailed, the label reverted to “Good Beer, No Shit” and Flying Dog gave its regulators a big middle finger by saying “shit” in five other places on the bottle, too.

A year after that victory, the brewery picked a new fight, this time with a Colorado statute that banned bar owners from permitting verbal profanity that could lead to a brawl. A difficult measure to enforce, for sure, but that wasn’t Stranahan’s problem with it. “I take very seriously the responsibility to defend our rights against bullying bureaucrats,” he said in a news release at the time.

Today, in its Instagram and Twitter profiles, Flying Dog declares: “We are craft beer crusaders who stand tall and never eat shit.” When you take the brewery tour in Frederick and pass through hallways splashed with gonzo murals, you don’t just drink in the trippy tale of the Innocents retiring to far-flung barstools beneath a portrait of a nice, big flying dog—you also hear all about Caruso’s crusade to defend the Raging Bitch.

***

Every time Caruso tells the story, he makes a gushing and defensive show of highlighting all the female buy-in for the name. One employee he gut-checked “was in her mid-twenties,” Caruso tells me. “She said, ‘I love it. It’s perfect, but I have to ask my mom.’ She came back the next day: ‘My mom loves it.’ ”

With Mom’s say-so, Caruso turned to more women on staff. One said, “If you don’t do that, I’ll be forever disappointed in you.”

Then there was the time he was in New York, focus-grouping the Bitch with the lady ball-busters of hedge funds and investment banks. “I went down to the Financial District to do a happy hour,” Caruso explained at the Newseum. “It was all women, all the financial people from Wall Street, all women. . . . I had a bunch of Raging Bitch swag—you know, T-shirts and so forth. You would have thought I was bringing rice to people who hadn’t eaten for two weeks. They attacked. I almost got a black eye. . . . They were pulling down, like, their pants and their shirts to show me the Raging Bitch T-shirt underneath, and I said, ‘Well, it’s really great to be here at the happy hour.’ And they said, ‘Jim, this is not a happy hour. This is a bitch session.’ ”

A few sentences later, he added: “This beer has empowered women in ways I can’t really relate to.”

So, Caruso says, he used the name.

Bitch is a dog. Yes, we know there’s other connotations, but all the ladies voted to do the name.

After the Michigan Liquor Control Commission banned the Bitch on grounds that it was “offensive, stereotypical, sexist, derogatory and demeaning” to women, Caruso appealed. His initial argument was simple: Raging Bitch was an innocent gag, nothing sinister. In so doing, he left out the bit about Mom, but he did say: “Servers told me, ‘It’s just fun to sell—we just like saying bitch. It’s just fun.’ ”

The commission, which had already vetoed Bubbly Bitch, Royal Bitch, and Mad Bitch from other companies, wasn’t nearly so amused. An assistant attorney general representing the state went onto the brewery’s website and saw that the marketing material read: “Raging Bitch, if you’re lucky, your bitch will look this sexy after 20 years.” At a hearing, the assistant AG noted, “I’m not suggesting that you censor the website, but . . . I’ve been a dog owner all my life—I don’t know many dogs that last 20 years.” The commission shot down the appeal.

At that point, Caruso decided not to go gentle into the graveyard of unlicensed adult beverages. He lawyered up. “I am for this: Keep the government out of the bedroom and the boardroom,” he tells me. “I am for massive personal freedom, and I am socially for anything. Frank Sinatra said it best: They said, ‘Mr. Sinatra, how do you feel about drugs?’ He said, ‘I’m for whatever gets you through the night.’ As a libertarian, you know what I’m for? I’m for happiness.”

With Gura now onboard, Flying Dog sued the commission—and all of its members individually. This time, Caruso walked in to face his oppressors with a more sophisticated, if thinly veiled, defense of the company’s right to hate on women: It was just free speech.

“It was such a fun case because the state of Michigan was so completely off its rocker,” Gura told the Newseum audience. “. . . Our argument was really simple. Look, you may not like the beer—you’re not required to agree that this is a fantastic label. You’re not required to like the product or like Flying Dog’s message, but Flying Dog does have the right to communicate with its public, and people have the right to hear Flying Dog’s message. And that message is: Raging Bitch.”

The brewery lost the case. But Caruso again appealed. At one point, there was an opportunity to settle. “I’m like, I’d rather lose what they’re offering than for a second give in to their politically correct, appointed-bureaucratic bullshit. It’s just not who we are.”

Anyway, by his reasoning, “they are just words. You should be afraid of evil and violence. You shouldn’t be afraid of a word whose etymology is ‘dog.’”

***

Don’t be mistaken: Caruso loves beer. He can remember his first timid sips as a five-year-old having dinner with his Russian grandparents, who didn’t trust the water. He grew up in Cleveland’s answer to Little Italy, idolizing Sinatra and (yes) Hunter S. Thompson, the most famous libertarian America may have ever had, who—coincidence—turned out to be the neighbor of Caruso’s future business partner George Stranahan.

Babushka’s dinners notwithstanding, Caruso didn’t come up in the beer world. He holds undergraduate and graduate degrees in economics. One of his first gigs was district manager at Denny’s, responsible for 80 diners’ worth of Lumberjack Slams. Then the company that owns the Village Inn Pancake House headhunted him out of grad school. Bill Carlino, a former industry reporter, says the Pancake House wanted “a young guy to reinvigorate the chain.” A maverick.

After seven years as a breakfast exec, Caruso joined up with future Colorado governor John Hickenlooper, who at the time was busy converting historic buildings into brewpubs. Eventually, the two would team up with Stranahan to turn an old Denver laundry building into a brewery.

In the decades since, microbrews have become a big thing and Caruso has ceased to be the fresh young guy on the scene. But while he may be 30 or 40 years older than most of his employees, Caruso prides himself on his youthful vibe, his flat, open, uncorporate management style. He loves being the kind of boss you can say “f—” around. “If you’ve worked for Flying Dog for any length of time, you’ll almost be unemployable,” Caruso says. “You’ll feel like you’ve been put in a straitjacket.”

After visiting Flying Dog a few times, I get it. Working there isn’t just a job—it’s a lifestyle. The staff parking lot is filled with cars bearing Flying Dog bumper stickers. Bartenders come in on their days off to have beers with their buddies, who are also their coworkers, who usually also have beards and/or tattoos. Sales director Heather Ault has Ralph Steadman’s Flying Dog bat wings on her wrist. Rohry Flood, a digital guy, asked Steadman to sign his arm with a Sharpie, then had a tattoo artist make the autograph permanent.

“There is a sense of collective consciousness here,” says Weston, the communications director.

In a job ad for a DC sales rep, Flying Dog says it’s looking for someone “to drink our Kool-Aid and spread the gospel of Gonzo and Good Beer.” The mission: “to convert non-buyers into believers.”

Each year, Caruso holds a daylong retreat at which any employee, from its CEO to its variety-pack assembler, can pitch new beers. At other breweries, trends get chased. At Flying Dog, Caruso says, “we start with ‘We like it.’ ”

The winning brews from that day—called Brewhouse Rarities—are supposed to “push to the edge of the box,” in the words of chief operating officer Matt Brophy, echoing his boss. Caruso told me a handful of times: “Everything interesting is at the edge.”

The Rarities should be pitched with feeling, such as one submission from this year ambitiously set to the tune of “Ice Ice Baby.” (It fell charmingly apart on the first verse.) And definitely with a story, like a beer that promises to be exactly what you want moonwalking past your lips on the plane ride home from an eight-day Vegas bender with Gary Busey.

And you better not stop there. For his beer’s release party, one of the guys who won at Rarities last year “booked the band, had a piñata made up of the bottle. He went all in and invited all his friends and family,” says Ben Savage, the chief marketing officer. “Now, unfortunately for everyone else, that’s the standard.”

Although its C suite insists nothing Flying Dog does is for marketing’s sake, the brewery’s marketing almost perfectly manages to transfer that feeling of belonging to its “fans”—the company’s word. (“I think ‘customers’ is weird,” says Savage. “We’re not Walmart.”) Flying Dog posts to Instagram at least once a day to tell fans what’s cool (sexting = yes, Pokémon = no), but in a tone that suggests they already agree. The company eschews advertising in favor of events. “We come up with an idea at 10 am on a Tuesday, and it’s in front of our fans at 10:15 am,” says Savage, “because we love the idea, we love the story, we love what it says about us as people.”

This summer, Flying Dog brought in a tattoo artist and promised discounts in the tasting room for life to anyone with a Flying Dog tattoo. #GoodInkNoShit. The event sold out. It hosts an annual 0.1-kilometer run called Sprint for Spat, where, after running halfway, participants rehydrate with shooters of Pearl Necklace. #ZeroTrainingRequired.

As Caruso puts it, “When you are authentic people who aren’t following a script but are the right people for the company, being ourselves is the marketing.”

***

Of course, beer has always been caught up in identity. You are what you drink. See: “Coors—Born in the Rockies,” “Busch—Head for the Mountains.” Against this brawny backdrop, craft beer swaggered in as the punk rocker. It was antiestablishment and in-your-face.

Flying Dog, with its irreverence and mythmaking, immediately prospered. “What they have mastered is polarizing people,” says Brett Robison, general manager of the Takoma Park restaurant/bar Republic. “Without that edge, the marketing, and the attitude, I don’t think they would have created as many opportunities for people to try their beer.”

But when Flying Dog got started, the country had only a couple hundred independent breweries. Now there are almost 5,000. According to the Brewers Association, a new one opens every 12 hours. This year, for the first time since the recent boom began, sales across the industry have slowed.

There’s been talk of a “beer bubble” and speculation about when it will burst. There’s also talk about how the industry will have to bring on new, more diverse drinkers: women, gays and lesbians, minorities, basically all the types of people the hetero-white-guy world of craft beer never had to woo before.

Where does that leave a cocksure brand that loves to own its politics?

Amy Bowman, owner of the Black Squirrel in Adams Morgan, a beer nirvana for DC drinkers, thinks Flying Dog is good but doesn’t stock it on principle. “If a new brewery opens in Shaw and calls their beer Raging Bitch, would that go over well?” she asks.

Says Sara Bondioli, vice president of DC Homebrewers: “I’ve heard discussions in the beer community among friends of mine and in forums. People seem to be recognizing [the problem of sexist labels], including men—they’re finding it offensive as well.”

The same way that “Zonk,” a regular in the Beer Advocate online forums and the father of a seven- and a three-year-old, says he doesn’t want to keep Flying Dog’s Doggie-Style in his fridge (“Leads to too many unwanted questions”), Camden Yards doesn’t want Raging Bitch on its stadium menus—the beer’s for sale only as the “Belgian-Style IPA.”

If a new brewery opens in Shaw and calls their beer Raging Bitch, would that go over well?

On the other hand, what do the Orioles know? In a bigger, more crowded market, maybe carving out a niche isn’t a business liability at all. “Jim and I have talked about it, and we’re lucky in the sense that we are not trying to appeal to everyone,” says Savage, the marketing officer. “I think that’s where brands get into trouble. They try to water down who they are to appeal to more people.”

Flying Dog’s beers aren’t the only frat-boy labels on shelves—see: Clown Shoes’ Tramp Stamp and Pig Minds Brewing Co.’s PD Blueberry Ale, whose label art of a woman with her panties by her ankles leaves little question about what “PD” stands for. But Flying Dog epitomizes a lot of what repels and sometimes attracts people to the world of craft beer. It’s brash and it’s bold. The message is Raging Bitch. Says Caruso: “The more you scratch the surface of Flying Dog, the more you find out it’s as weird and interesting and unusual and expressive as it might appear.” He pauses. “You go, ‘Wow, I didn’t know you guys were this cool.’ ”

If you don’t agree, no problem: “Don’t buy the beer.”

***

It took five years, but in March 2015 Flying Dog won the day in Michigan. The state owed Flying Dog $100,000 in attorneys’ fees plus about $40,000 in damages.

“It wasn’t for publicity, it wasn’t for marketing,” Caruso says. “The question should be ‘Jim, if no one ever knew that you sued Michigan, would you do it?’ Absolutely. One hundred percent.”

But people were always going to know. Big trials are expensive, Flying Dog is the biggest brewery around Washington, and it hired a big-deal lawyer. Even if these things weren’t true, people were always going to know. Why? Because Caruso held a news conference at the National Press Club to announce that the brewery had sued Michigan and was starting a 1st Amendment Society with the kitty. By his side, Alan Gura. Before them both? Six-packs of Raging Bitch.

The 1st Amendment Society promises to “advocate and educate on the First Amendment and organize events that promote the arts, journalism and civil liberties.” So far, besides the party/panel at the Newseum, it has held talks on banned books such as Allen Ginsberg’s Howl. Flying Dog provided beer for the Charles Koch Foundation–cosponsored reception for Can We Take a Joke?, a one-sided documentary about PC culture, and sponsored a launch party for Index on Censorship, a London magazine promoting free expression.

The political correctness Caruso despises is different from just plain correctness, but that’s not a difference he engages. Last year, to celebrate the brewery’s 25th anniversary, the people of Flying Dog released a new Belgian-style India Pale Ale brewed with pineapple, mango, and passionfruit. (“For years she’s gone walking. And time after glorious time, she never disappoints.”) The brew was notably sweet, but not more sweet than it was bitter.

They named it Tropical Bitch.

Associate editor Amanda Whiting (@amandamwhiting on Twitter) can be reached at awhiting@washingtonian.com.